STOLEN CHILDHOODS

BY CHARLIE CUSTER

STOLEN CHILDHOODS

BY CHARLIE CUSTER

Child kidnappings leave scars across generations

那些再也没有回家的孩子们

“It's just like a dream now,” says Wang Qingshun, sitting in an overstuffed hotel room armchair in Hangzhou. “I remember my home like it was a painting. I remember my father's face. The rest of it, I don't remember much at all.” He says it matter-of-factly, as though we all have these issues when trying to remember our childhoods. But Wang's childhood has not faded from his memory. Rather, it was stolen by the kidnappers who snatched him from his home when he was just four or fi ve years old.

“I think my father was chasing me to spank me,” he says, “and I was hiding somewhere. Then it gets blurry; I remember being in a car, driving past fi elds of rapeseed fl owers, crossing mountains, and then getting onto a train. How I got here, I have no idea.”

Even the basic details of Wang's life—the things we all take for granted—are unclear. He does not know his birthday or his actual age, though he believes he was kidnapped in 1988. He does not know where he's from, though based on his accent as a child, and some other factors, he believes he may be from Sichuan Province. Even his name is unclear. Wang Qingshun is the name he was given by his “adoptive” parents, the people who bought him from the kidnappers. He remembers his original name was Li Yong. But which Li and which Yong? He can't be truly sure.

Wang's fate was not uncommon for children from his area at the time. “I remember that kids were often kidnapped and sold away from my original home,” says Wang. “It felt like when the Japanese devils invaded China; whenever someone mentioned the news [about kidnappings] people would get scared.”

But this is no scare story from Chinese history, and the problem remains as prevalent today as it was when Wang was kidnapped back in 1988. As Wang sits in the hotel room trying to remember more of his early childhood, parents all across China are experiencing the same horror that Wang's birth parents must have experienced the day he disappeared. Decades after Wang's kidnapping, children are still being taken and sold by traff i ckers at an alarming rate.

Putting a precise number to the problem is diff i cult, and estimates range wildly. The Chinese government doesn't release statistics on the number of children kidnapped, although in the past it has pegged the number at around 10,000 per year. The U.S. State Department, in its annual report on human rights, pegs the number at around 20,000. Independent estimates range as high as 70,000.

“EVERYONE KNEW,” HE SAYS,“EVERYONE KNEW I WASN'T FROM THERE. ADULTS GENERALLY DIDN'T TALK ABOUT IT, BUT THE OTHER KIDS WOULD MAKE FUN OF ME.”

The reason for the discrepancy is that the only real numbers to work with are the number of children rescued from traff i cking gangs each year. “If we use this data to guess at the hidden data of how many children are kidnapped each year, and assume for example that one in three or one in fi ve are rescued, that will give you an approximate number,” says Pi Yijun, a professor at the China University of Political Science and Law. “There's really no more reliable method than that.”

In 2011, Chinese police rescued 8,660 kidnapped children. Using Pi's examples as a range, we might roughly guess that in that same year, between 25,980 and 43,300 children were kidnapped. But there's simply no way to be sure. What is clear is that kidnapping is a serious problem. “You can see that there has not been any major drop in this kind of crime,” Pi Yijun says.

Although decades have gone by, the business of traff i cking in stolen children hasn't changed much; what happened to Wang Qingshun is still typical of what happens to young boys who are taken by traff i ckers. Wang was sold to a new family. His new “adoptive” parents had given birth to only daughters, and as they were ageing they felt that they might not be able to conceive a son, but they wanted one. A relative had a line on a child they could buy, and they jumped at the chance. It's not clear whether they knew that Wang had been kidnapped when they chose to purchase him, but they certainly knew he wasn't being adopted through off i cial channels.

Wang's origins became clear when he arrived at his new home, though, because he made them clear himself. He told neighbors he was called Li Yong, not Wang Qingshun. He spoke with an accent so thick practically no one in his new Zhejiang home could understand him. In kindergarten, he says he got suspended repeatedly for getting in fi ghts because he hit other boys who teased him for having “been purchased” (he claims he once even smashed something over another kid's head in response to the teasing).

“Everyone knew,” he says, “everyone knew I wasn't from there. Adults generally didn't talk about it, but the other kids would make fun of me.” Despite the fact that his having been purchased was common knowledge, it took over a decade before somebody fi nally picked up the phone and called the police.

To understand why, you've got to understand that in traditional Chinese society, having sons was of paramount importance. Because daughters, when married, generally moved in with their husband's family, a set of parents without a son would have no one to care for them in old age. Thus, in traditional society it was not uncommon for neighbors, friends, or family members to, essentially, give children to each other if one family had a surplus of sons but another had a def i cit. If you already had four sons but your brother in the next village had none, for example, you might send your fifth son to be raised in his home. This was considered normal, and in the modern area, it's still common in some areas for families to raise children that aren't theirs. And although Wang's case clearly involved some lawbreaking, many people are hesitant to get involved in other people's business. The fear ofreshi(惹事)—trouble for oneself—may help to explain why no one called the police on Wang Qingshun's adoptive parents for such a long time.

When the police fi nally did get involved, there wasn't much they could do. Wang's adoptive father and his uncle were arrested and ultimately fi ned for having been involved in child traff i cking, but after that the case went cold. Wang had been passed from handler to handler along his journey to his new parents, and although the police found the fi rst of these men, they never got further than that.

Wang Zun and his wife Li Guangying from Kunming, Yunnan Province, hold a picture of their son who was kidnapped when he was only two weeks old. He has been missing ever since.

This is typical of traff i cking cases, which have proven notoriously diff i cult to crack. China has a national-level anti-kidnapping task force that oversees large-scale operations to take down traff i cking rings and criminal gangs, and traff i ckers are punished severely—convicted child traff i ckers are often sentenced to death and executed. But solving individual cases often requires tracing back through numerous handlers and intermediaries, securing cooperation from local police forces in a variety of locations to attempt to ascertain the child's point of origin, and collecting information from victims who are often too young or too traumatized to be fully aware of what happened to them. Even when a case is solved and a child is rescued, this doesn't mean the police will be able to fi nd the child's original family.

Another problem is that it isn't always clear whether or not a child has been kidnapped. In the absence of concrete proof like a video recording of the kidnapping, police will be inclined to treat the case as a missing persons issue, at least initially, and since uncovering clues in a kidnapping case can be extremely diff i cult, many cases are conf i rmed as kidnappings only after the child has been rescued. Police and parents must struggle with the knowledge that a missing child could have been kidnapped, but he or she also could have run away, or even somehow have been killed.

And the situation is further complicated by the fact that when children are rescued, what seems to be morally right isn't always what's best for the child. In Wang's case, for example, though he was kidnapped and sold, he was also treated well and raised as a son by his adoptive family, who he now considers to be his parents. Were he to have been ripped away from them, years after his kidnapping, and returned to his original family, it might have caused more psychological damage.

Wang's situation is comparatively lucky, though. Not all kidnapped kids are sold to new families. While sale into adoption (both domestically and abroad) is the most common motivation for the kidnappings of infants and toddlers in China, there are cases of children being kidnapped right up through their teens.

Older children may be taken by traff i ckers for use in street gangs. Sometimes they are made to beg on the street.Sometimes they are made to perform street theater, contortions, and acrobatics for change. And, like something out of a Dickensian nightmare, some are forced to become pickpockets.

Two-year-old Jing Huitong holding a drawing of “father” and “mother” in Jinjiang Infant Asylum, Fujian Province—home to 24 kidnapped children. Rescued children who can't find their parents have been coming here since 2005.

“PROBABLY ALMOST 100 PERCENT OF THE TIME, THEY HAVE BEEN KIDNAPPED AND ARE BEING CONTROLLED BY ADULTS”

Du Chengfei, the director at the Xinxing Aid Center for Street Children in Baoji, Sichuan Province, says that the street children he sees who've been pickpockets are nearly always Uyghur kids, and “probably almost 100 percent of the time, they have been kidnapped and are being controlled by adults.”

In the cases of Uyghurs and other older street children, the kidnapping often works something like this: fi rst, thechild is approached by a traff i cker or someone aff i liated with the traff i ckers. This person may be someone the child knows, like an extended family member or acquaintance. This person convinces the child to come with them and get a job in a city on China's east coast. The child is told that their parents know about this arrangement, and that they'll be helping their family—kidnapped children almost always come from poor families—by earning money that will be sent home to their parents (this, of course, is a lie). When the child accepts the offer, they're taken to a new city and integrated into a street gang that likely includes other children but is overseen by adults who control what the children do, watch them when they're on the street and take the money that they've earned.

After 15 years of separation, in March, 2013, Wang Mofeng and his wife from Anhui Province were finally reunited with their son Wang Xiaolei in Fuqing City, Fujian Province, thanks to the efforts of the local police

THE CHILD IS TOLD THAT THEIR PARENTS KNOW ABOUT THIS ARRANGEMENT, AND THAT THEY'LL BE HELPING THEIR FAMILY

“Older kids are often sold into criminal organizations and used like tools,” says Pi Yijun, “because people don't pay too much attention to child criminals, and their demands are very low, as longas they can eat and play they're okay. In some big cities they are made criminal accessories, a tool of [serious] criminals, but mostly they're used for pickpocketing.”

Kidnapping cases involving street children can be diff i cult to solve because often, by the time police or other authorities get in contact with the child, the child has been tricked and abused by other adults for months or years on end. Many street children develop a deep distrust of adults. At Xinxing, Du Chengfei says, “some [street] children are extremely wary. They don't trust you, and they may give you a completely fake number”or other fake contact information. And while Xinxing is a privately-run rescue center that has the time and resources to wait patiently as the children go through therapy and counseling, and slowly begin to trust again, most Chinese rescue centers don't have that luxury. Even the street children lucky enough to be rescued often end up back out on the street if their origins cannot be quickly determined.

Teens are also sometimes kidnapped by traff i cking gangs, but usually when a child that old is taken, they're not sold into adoption or a life on the street. Generally, they're taken, by force, and sold into a life of slave labor (for boys) or forced prostitution (for girls).

This is the world that Yuan Cheng, a farmer from a remote village in Hebei, began to uncover when his 15-year-old son Yuan Xueyu disappeared from a construction site where he had been working back in 2007.

Yuan and his wife had hemmed and hawed about whether or not to let their son travel to Zhengzhou to work at such a young age, but the boy was determined to go and eventually his family relented. “We thought: he's not in school, and there's nothing for him to do at home, perhaps he can see the world and learn some skills,” said Yuan. Plus, he was going with friends from their village; they would be living together and it all seemed safe enough.

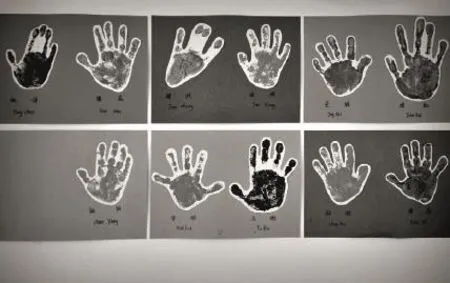

On a classroom wall of Jinjiang Infant Asylum hangs the hand prints of kidnapped children wishing to return home one day

But one day on a construction project, Yuan Xueyu was sent from one fl oor to another to retrieve a tool, and he never came back. What happened to him isn't clear. But when Yuan Cheng went to Zhengzhou to look into the disappearance himself, he began to hear about other disappearances in the area, and rumors that the kids were being sold into illegal brick kilns, where they were being forced to work without pay or freedom of movement.

Yuan reported all of this to the police, of course, but he also banded together with other parents of missing children and took things into his own hands. He and a small group of parents began researching, locating, and visiting these illegal brick kilns whenever they could.“The conditions are really indescribable,” says Yuan.“The stuff they eat is like the things we feed our pigs; there are no beds in the sleeping area so they just sleep on the ground. And the work, especially in brick kilns, they work barefoot or in slippers. You can't wear shoes because [the guards are] afraid you'll be able to run away easily.”

And although there are plenty of adults working in these squalid conditions, Yuan and his fellow parents also found plenty of children. “Between the kids we've found [who escaped] and the ones we went in and rescued ourselves, it's probably over 100,” says Yuan.

Yuan Cheng is still looking for his son, who unfortunately is not one of the hundred-or-so his group has rescued. He says that his search has become much harder; increased media focus on the problem and some national reporting about the black kilns back in 2007 and 2008 has made their operators warier and more cautious, and the kilns are now hard to fi nd and even harder to sneak in and out of.

The rise of social media in China has led to increased awareness of the country's kidnapping problem, and the advent of the internet has been a boon for parents of missing children, who can now browse websites that collate relevant news, reports, and photos, and (in the case of the most popular organization, “Baby Come Home”, 宝贝回家) even assign case workers to assist the parents with their search. But the internet has not solved the problem, and children are still disappearing at an alarming rate.