Light Through Yonder Window Breaks

by+Xuan+Kang

In one Chinese City live two power- ful rival families: Luo and Zhu. They became as incompatible as fire and water over a trivial dispute. The only son of the Luo family sneaks into a ball held by the Zhu family and falls in love with a Zhu daughter. The plot is more than a little reminiscent of Shakespeares Romeo and Juliet, except that characters ride bicycles, dye their hair, wear sunglasses, drink beer, listen to rock music, and chat in distinct Chinese dialects. The play is indeed a Chinese adaptation of Romeo and Juliet.

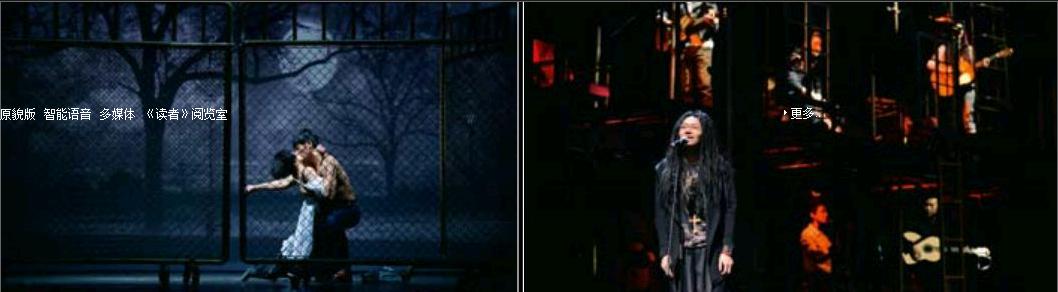

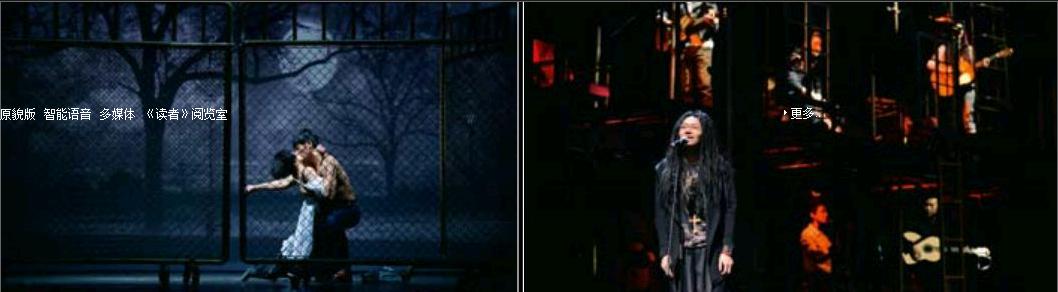

At the invitation of the 42nd Hong Kong Arts Festival, renowned Chinese director Tian Qinxin staged Romeo and Juliet to commemorate Shakespeares 450th birthday. Throughout late March 2014, Tians production of Romeo and Juliet was staged at the National Theater of China in Beijing. The play is scheduled to tour to other Chinese cities including Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Shanghai, with an expected run of at least 100 performances in China in 2014.

A Contemporary Chinese Story

Romeo and Juliet, as with much of Shakespeares canon, has been adapted for the screen dozens of times in addition to countless productions around the world. A wide array of artists with contrasting cultural backgrounds has generated different interpretations of the story. In Baz Luhrmanns 1996 MTV-generation adaptation, Romeo+Juliet, Leonardo DiCaprios Romeo is an agitated and rebellious, but sentimental young man. In 2007, Japan produced an animated version, which made Verona a “sky city”, and surrounded the lovers with elements of fantasy. The romance is soaked in strong Japanese flavor, delicate and mysterious.

Tians interpretation of Romeo and Juliet, as she puts it, “is a story of modern developing China.” She explains that Shakespeares plays are a bit high-brow and inaccessible to ordinary Chinese people. So, to better frame the Bard for a new audience, Tian became a “translation machine”: She decoded the original work and transformed it into a Chinese story.

The setting was changed from Italys Verona to an anonymous Chinese city in which the Luo and Zhu families reside. Each family enforces its own specific rules, but shares the prohibition on marrying into the other house. The root of the feud is trivial to say the least: the Zhu family was accused of stealing four bicycles from the Luo. “Sometimes, such wars are so simple,” Tian explains. “Widespread, massive hatred can be generated by something so paltry.”

In keeping with that theme, fluorescent bicycles frequently roll across the stage. In the original, horses are mentioned as transportation, and weapons are swords. In Tians version, Romeo wears a trendy outfit and rides a fluorescent bicycle. “Hes a masculine but slightly decadent guy,” Tian opines.

In the play, Tian included many elements to allude to “a developing China” —adding rock music, conversations peppered with pigeon English, group dancing, and telephone poles packed with utility cables. The most conspicuous directorial choice is the fluorescent bicycles. Tian considers them “nostalgic yet fashionable,” representing Chinas disappearing bicycle era and a trendy yet rapidly developing country.

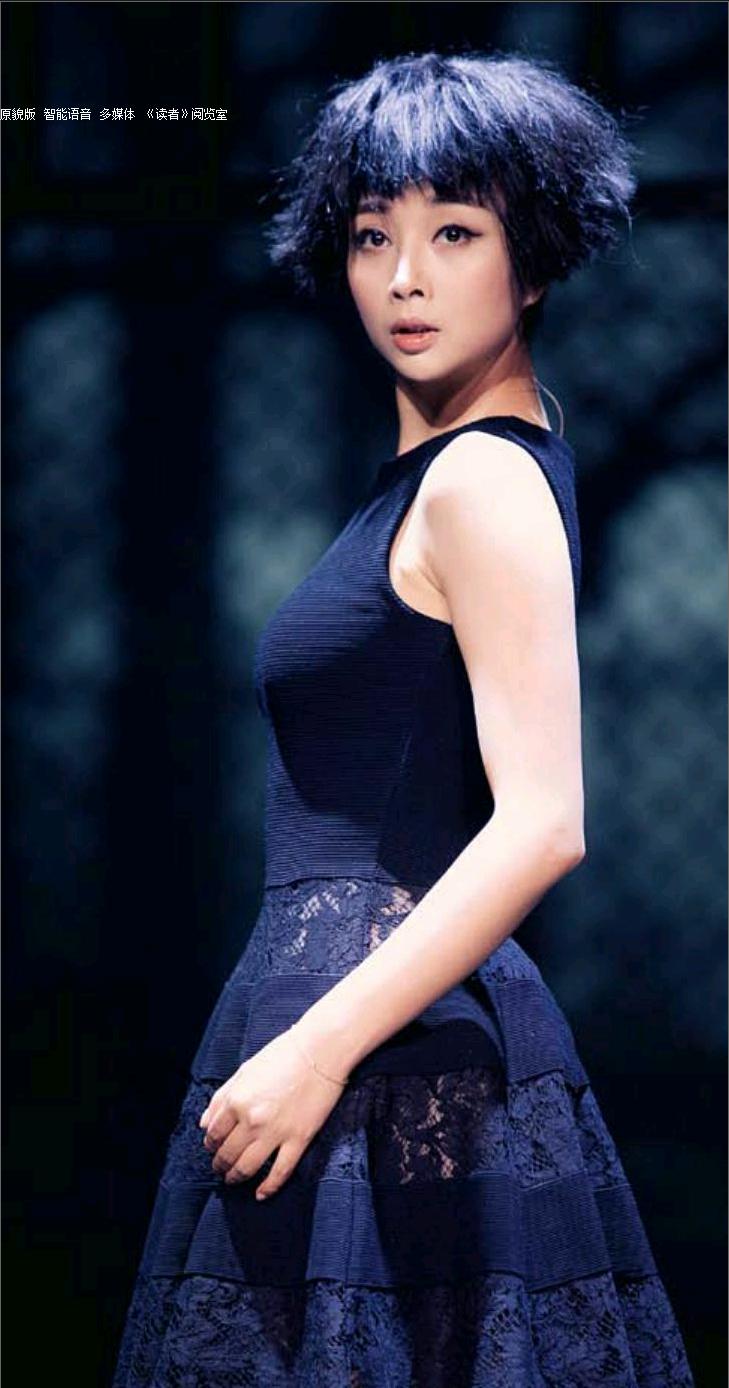

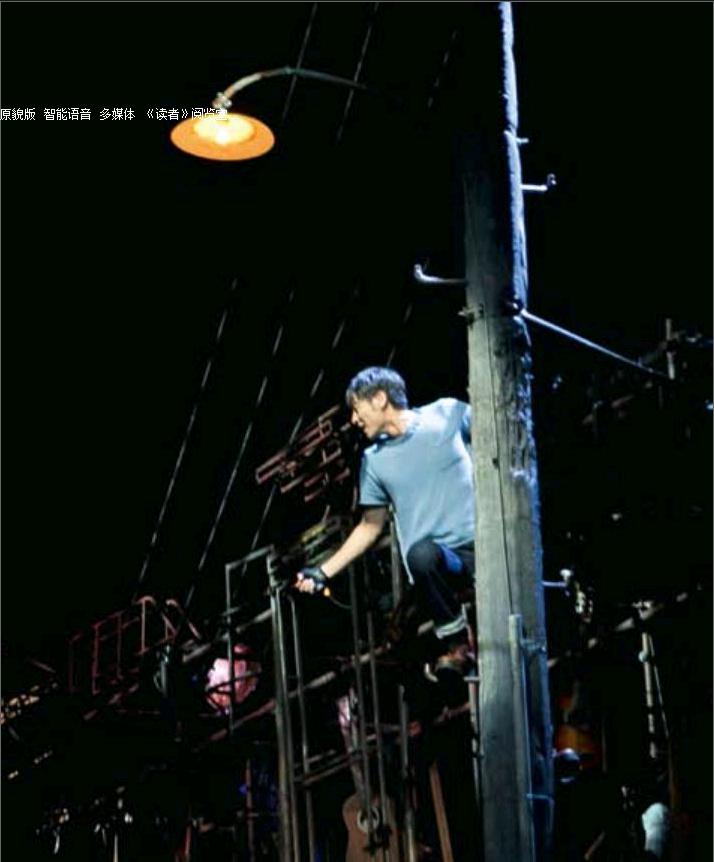

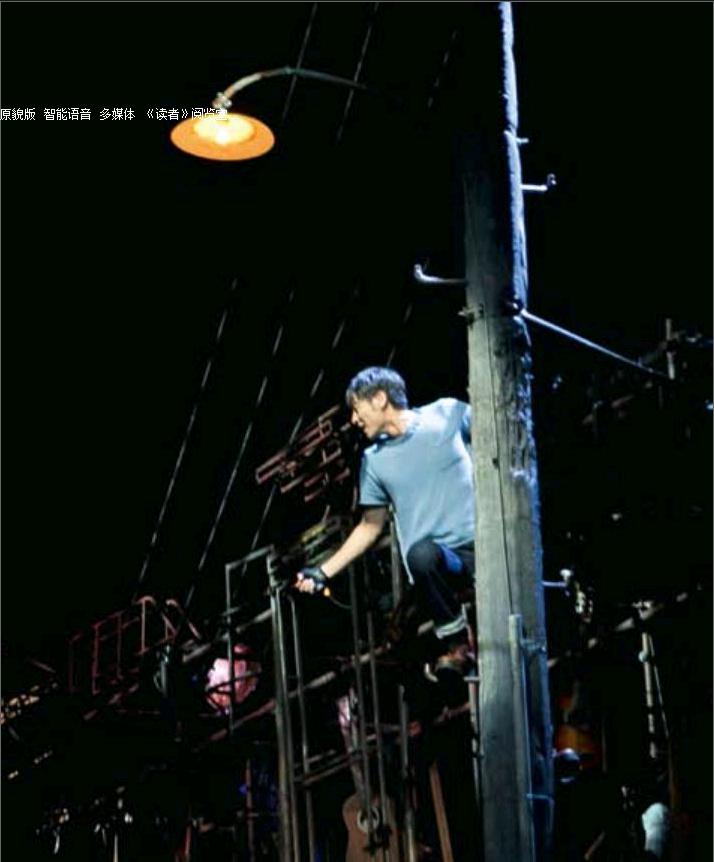

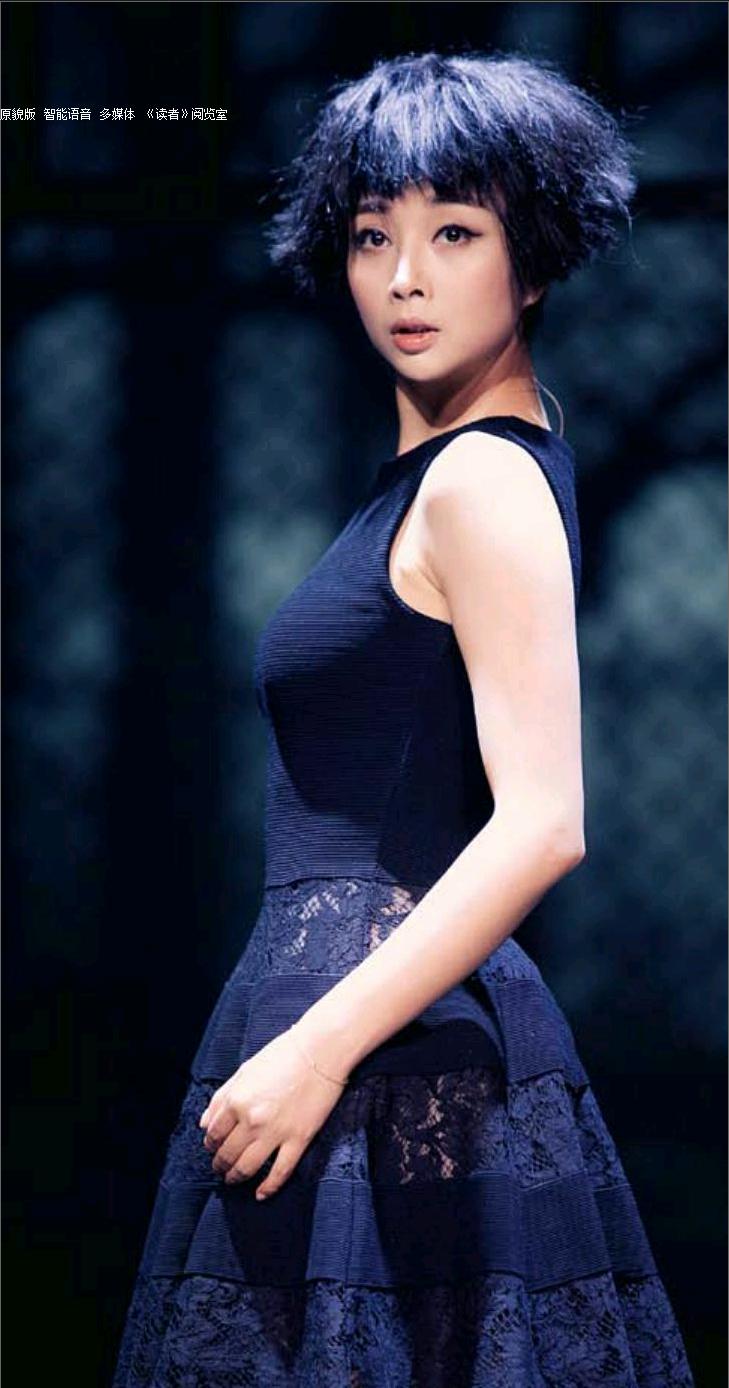

The early highlight, when the two young people pledge love to each other, is sated with strong Chinese flavor in Tians production. At the ball, short-haired Juliet, wearing a sexy black mini-skirt, has climbed a ladder to fix light bulbs when Romeo sneaks in. To dance club music, the couple falls for each other. In the original work, they dont get together until after the ball is over, when Romeo approaches her iconic balcony. In Tians production, both characters scale telephone poles on opposite sides of the stage. After climbing the poles, the lovers profess their feelings“in the air.” To Tian, such poles are typical to China, unforgettable for several generations of Chinese people.

About Pure Love

With a decade of experience as a director, Tian has been striving to bring Chinese culture to the stage. Romeo and Juliet is not her first staging of Shakespeare. In 2008, she directed Ming, which incorporated many elements from the Shakespearean tragedy King Lear. That adaptation was even bolder with Tians considerable changes. Even the stage design was brimming with Chinese flavor.

Five and a half years later, when she found a second chance to stage Shakespeare, and this time his most popular work, she opted for more prudence and didnt make as many changes. During preproduction, Tian looked to the classic translation by Zhu Shenghao (1912-1944)as well as that of Liang Shiqiu (1903-1987), two of the most revered Chinese translators of Shakespeare. She strictly sticks to the scene structure of the original, and many lines in her version are very close to the original. Tian explains that she hoped to“salute the masterpiece while producing an adaption tailored for Chinese spectators.”

To “salute the masterpiece,” Tian hopes to deliver Shakespeares ideas and make her audience feel the heart of the play. The reason the story of star-crossed lovers is so timeless is not just the romance, but because of its accurate depiction of lifes natural needs and desires.

Four centuries ago, British understanding of love apparently didnt differ much from today. However, in traditional Chinese culture, “pure love” is not a common subject. In both ancient and modern Chinese dramas, the subject of love is often accompanied by obstacles, such as money, loyalty and conspiracy. Very few depictions of love are as pure, positive and powerful as that of Romeo and Juliet. In Tians version, one scene depicts her understanding of Chinese attitudes towards love and marriage. At the lovers secret wedding, when the couple places their hands on the Bible, Juliets nurse speaks words hearkening to those frequently heard at Chinese weddings in the 1970s and 1980s, and even still today: “You two should love and respect each other, promote mutual progress, respect your bosses, love your parents on both sides, and visit your parents homes often. You should help each other to conquer weaknesses and repay your families, your work places, and society.” In China, marriage is not just a matter between two people, but a contract between families. It is even more a social ritual.

And in Chinas educational system, love is a topic parents and teachers hardly ever address. “In this way, some teenagers can only make guesses about love based on what they see in books,” says Tian. “Thats why this play is so valuable.”

Through the play, Tian hopes to see more positive conversation and publicity about love in China. “To me, the play has nothing to do with extreme behavior such as suicide,” she concludes. “Its about Westerners understanding and glorification of pure love.”