Kurbanjan Samat:The Photographer

by+Wang+Qi

Kurbanjan Samat couldnt sleep the night of March 1, 2014, after hearing news that 29 people had been killed by eight Uygur assailants at Kunming Railway Station in Yunnan Province. Authorities identified the assailants as part of separatist forces from the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Kurbanjan felt enraged and upset when he saw Weibo bloggers carelessly blaming everyone from Xinjiang. He decided to retort to biases with a photo series titled Im from Xinjiang.

Every photo is a portrait snapped since late 2013, focusing on Xinjiang natives working in other parts of the country, even overseas. “Our people have been alienated, labeled violent and terrorists,” he frowned. “I wanted my pictures to show true faces.”

Kurbanjan has experienced many headaches due to his Xinjiang heritage. Soon after the Kunming Incident, he and his friends were searched by police in Beijing. He received phone calls from the local police station asking how long he was planning to stay in Beijing. “Im going to stay here forever!” he couldnt help but rage.“Send me to Babaoshan [a local cemetery] when I die!”

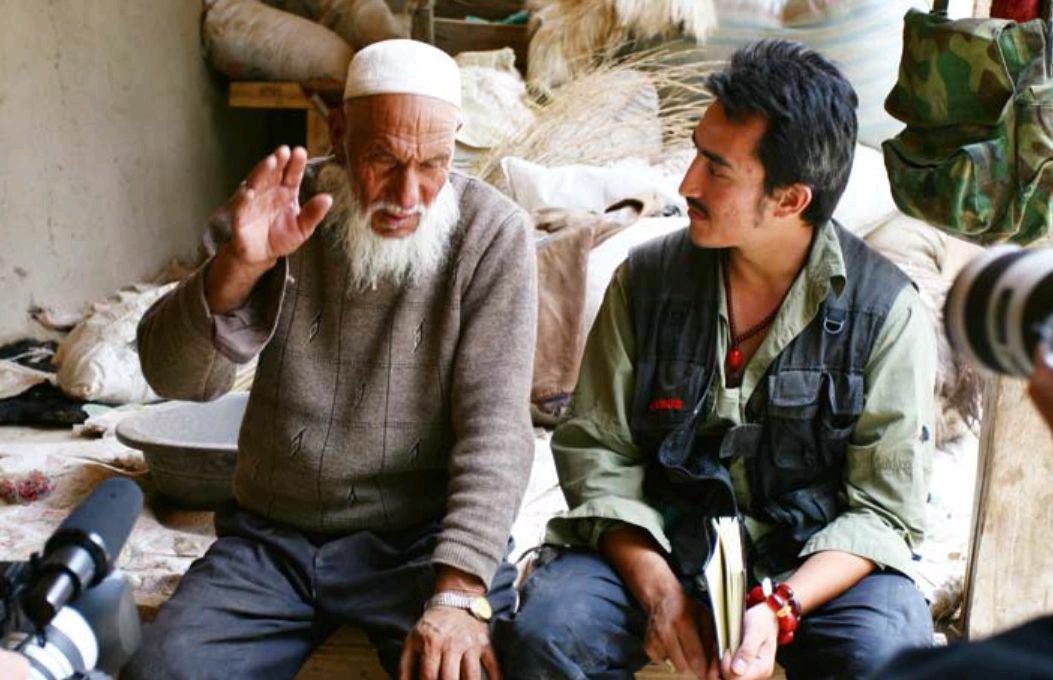

Born in Hotan, Xinjiang, in 1982, Kurbanjan has lived in Beijing for eight years. He bought his first camera at 17. His work experience is quite diverse: boxer, barbecue operator, and jade salesman, through which he met directors Meng Xiaocheng and Li Xiaodong from CCTV, Chinas biggest media outlet, who got him involved in shooting documentaries. In 2006, he came to Beijing to study at Communication University of China. He has been a camera operator for CCTV ever since.

After living and working in Beijing for so long, Kurbanjan has seldom felt uncomfortable because of his ethnicity. In college, he got along well with everyone, and was known as “Brother Jan.” His organizational skills are exceptional, and his performance at work is frequently lauded. His female colleagues affectionately nicknamed him “Banban.” The director seldom calls him by name but refers to him as “Little Kur,” appreciating his maturity, good looks, positive attitude and honesty. Nobody has a problem with him be-ing a Uygur from Xinjiang.

Bigotry derives from ignorance about Xinjiang people. “Xinjiang is inhabited by 13 ethnic groups, none of which can represent the entire population,” asserts Kurbanjan. The faces in his pictures already showcase diversity of 11 local peoples, including Uygur, Han, and Mongolian, among others. When completed, his photo series will comprehensively cover the diversity of people from all of the regions 13 ethnic groups and across ages and professions ranging from street peddlers to corporate executives. Common ground will hardly be found except that they all hail from Xinjiang.

“One reason to stay in Beijing is to serve as a bridge between the capital and Xinjiang,” Kurbanjan illustrates. “I want to interpret my people with photos.” Life in Beijing hasnt been easy, how-ever. Kicked out by his original host family, he had no place to go but a basement for seven yuan a night. He worked for a television station for a humble salary. After months of struggles, he finally collapsed. For an entire year, he did nothing but to stay inside, sleeping and playing online poker. Eventually, he found comfort by telling himself, “Things will be better next month.”

His great dream of bridging cultures was not the only thing helping him endure the bitterness of life in Beijing. He was lucky enough to find an opportunity that would fully utilize his talent.“He could make a fortune in jade,” a friend remarked, “but he made a different choice: Hes a TV guy.” He knew what he wanted.“Making documentaries has been a long-term dream, whatever it takes,” he insists.

Kurbanjan wanted to make Im from Xinjiang into a documentary film but he couldnt gather enough funding.

“Framing those people creates a mirror for my own face,” he continues. “They do share things in common. They are all openminded. Im narrow-minded, easily upset. I must learn from them. Also, they all do what they should, and toss away all their baggage.” He used to feel heavily burdened as a Uygur. “Im iconic,”he admits. “Im Kurbanjan when I do something beautifully, but Im a bad young Uygur when I screw up. Then I feel guilty for my people. Thats why my life has been uneasy.”

For a while, he was overly cautious about his behavior. He would spend a half hour collecting garbage off the street. “I feel much better now,” he smiles. “I dont care too much about things that arent about me. I try my best and strive not to let my parents down. Thats good enough!”

Kurbanjan opposes attaching anything political, such as “ethnic policy” or extremism, to Xinjiang people.

In a recent interview with a foreign journalist, he was asked if he had ever experienced discrimination. “What do you think of the ethnic policy?” he was asked. “Im not a politician,” he began reluctantly. “Why do you ask me such questions? Dont treat us this way if you care at all about our people. As a journalist, you are challenging us all the time. Are you worthy of your job? If you do care, show concern for our ordinary people and hear their actual voices.”

As planned, Kurbanjan is satisfied with 37 portraits of a planned 120. He will publish a photo album upon completion. His next step is to shoot each subject again in action shots depending on their character. “Ill put them into a documentary as soon as I find the money,” he notes. “A few bad apples can damage the image of an entire group, but correct understanding of the majority and a positive outlook can foster progress.”