Decoding the Dunhuang Grottoes

by+Huang+Liwei

Located at the western end of the Hexi Corridor in Gan- su Province, Dunhuang Grottoes include the Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang, the Western Thousand-Buddha Cave to its west, and the Yulin Grottoes in Guazhou, all of which share similar geography, historical context, content, and artistic characteristics. They didnt draw global attention until 1900, when a cave preserving Buddhist sutras was discovered in the desert.

Dunhuang Grottoes

The Mogao Grottoes, also known as the Thousand-Buddha Cave, tops the list of grottoes. It is located 25 kilometers southeast of Dunhuang City. Construction first began around AD 350 to 394 and spanned several dynasties.

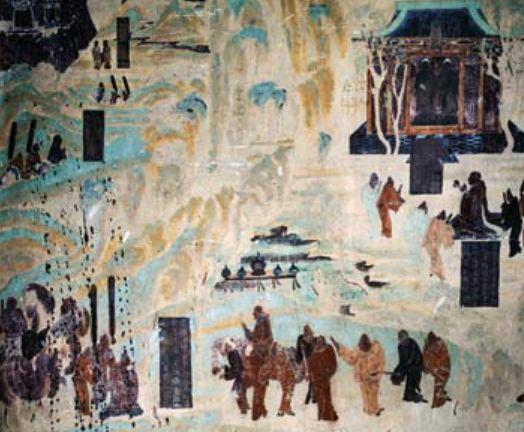

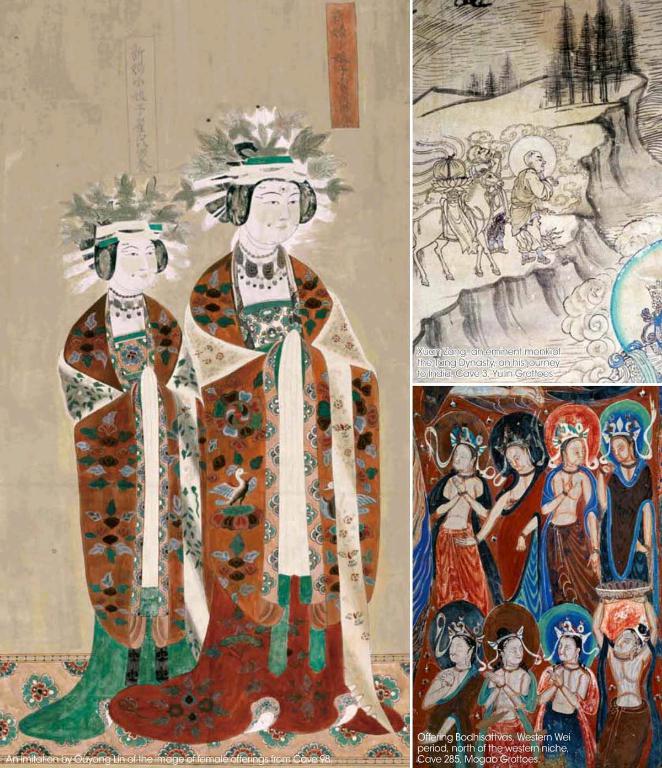

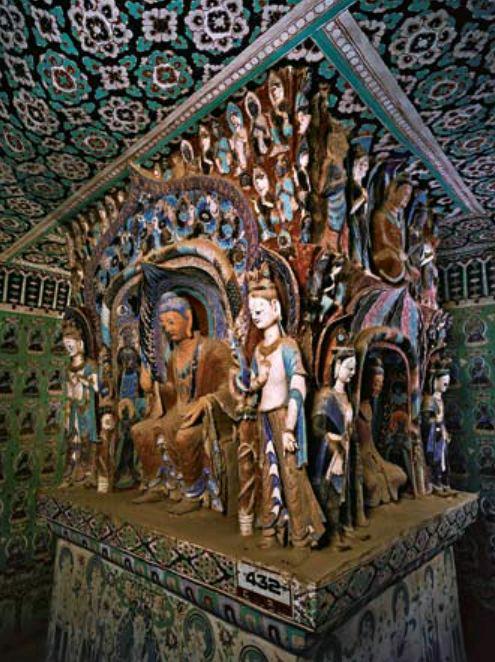

A total of 735 existing grottoes dating from the Northern Wei(386-534) to the Yuan (1271-1368) dynasties are now categorized in north and south areas. The southern area is the nucleus of the Mogao Grottoes and includes 487 grottoes, while the northern section has 248. A combination of paintings, sculptures and architecture, the Mogao Grottoes are most famous for their murals, found on the walls and ceilings of the caves and in niches, depicting Buddhist images and stories as well as prophets and deities. The images also touch on social topics such as hunting, farming, war, weddings, and funerals.

The moniker of the Western Thousand-Buddhist Cave derives from its location: west of the Mogao Grottoes near the Sounding Sand Hill. Included are 16 caves, most of which were dug during the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534).

The Yulin Grottoes are located 76 kilometers south of Guazhou County, a neighbor of Dunhuang, and include 42 grottoes. No historical records pinpoint the exact time of their construction, but due to the cave shapes and mural styles, experts date them earlier than the Sui and Tang dynasties (581-907). The Yulin Grottoes are also known for their murals, particularly several masterpieces of different dynasties.

Dunhuang Grottoes could be better preserved if not for extreme situations in modern times.

It was by chance that Wang Yuanlu, a Taoist priest residing near the Mogao Grottoes in 1900, discovered a square cave housing over 50,000 relics – writings, paintings, and embroideries from the 4th through 11th centuries.

The discovery attracted many archaeologists and antiquities traders from Western countries, who purchased the precious ancient books, records and murals cheaply from Wang and shipped them home, while other artifacts were either stolen or destroyed.

In 1944, a group of artists and scholars, led by Chang Shuhong(1904-1994), headed to Dunhuang and launched a new era of protection and study of the grottoes. The same year saw the founding of a research institute of Dunhuang art, which was renamed the Research Institute of Dunhuang Relics in 1950 and expanded into the Dunhuang Academy in 1984. Over the past 70 years, remarkable achievements have been made to study and protect the Dunhuang Grottoes. Over the last ten years in particular, state-of-theart technology has been employed in the archaeological progress.

Archaeological Report

The publication of the Report on Archaeological Study of Cave 266-275 in the Mogao Grottoes, the first volume of Collected Works of the Dunhuang Grottoes, in 2011 marked a new stage of archaeological study of the Dunhuang Grottoes. The book filled in remaining gaps in the comprehensive Chinese records despite the fact that illuminating data had already been collected in the 20th Century. Most measurements and other data were published by Western archaeologists and adventurers during the days following the initial discovery.

The publication of comprehensive archaeological reports on Dunhuang Grottoes has been a long-cherished dream of generations of Dunhuang researchers. Since the plan was conceived in the 1950s, the researchers have continued unremitting efforts, such as surveying the many caves. The first part of the report was finally published thanks to great endeavors of Fan Jinshi, president of the Dunhuang Academy, and her team, who formulated a long-term plan to produce a multi-volume Collected Works of the Dunhuang Grottoes back in the 1990s.

Collecting data for the book became the most difficult task due to irregular shapes of the caves and complicated composition of painted sculptures and murals. In the early days, archaeologists only estimated measurements in the dark caves and drew maps by hand. It usually took several months to finish a rough draft. There was so much work to do that precise data could not be guaranteed.

In the modern era, to obtain accurate image data of the structures, painted sculptures and murals in the caves, Dunhuang Academy uses a three-dimensional laser scanner and computer software. Moreover, modern mapping and surveying devices and other cutting-edge technology such as GPS and computer assistance have been introduced.

The report produced a comprehensive picture of 11 caves: their positions, structures, statues, murals, current condition, and inscriptions, through various means of documentation including text, maps, and photography. Sophisticated techniques were also used to scientifically analyze materials and pigments used on the murals and statues, thus enriching the archaeological report in a scientific way.

Further Discovery of the Northern Grottoes

For a long time, people paid greater attention to the southern section due to its gorgeous murals and statues in 487 caves, but few paid much attention to the northern part, which was used as the residential area for archaeological teams.

From 1988 to 1995, however, archaeologists led by Peng Jinzhang, a researcher from Dunhuang Academy, excavated the northern caves six times, increasing the number of labeled caves from 492 to 735 in Dunhuang. He determined the function and nature of the caves in the area as well as differences between north and south, proving that the northern caves were an important part of the Dunhuang grotto complex, based on valuable relics and distinct features and shapes of the caves.

During the excavations, numerous ruins and precious relics were discovered, many of which evidence cultural exchange between China and other countries.

Persian coins, for instance, were discovered in Cave B222, shattering previous theories that the Dunhuang region had little contact with the Middle East. The discovery of “international currency” of the Middle Ages also verifies the operation of trade routes during the era.

Copper crosses unearthed from Cave B105, the first such relics ever discovered in the Dunhuang region, evidence the existence of Nestorians during the Song Dynasty (960-1279).

A copy of the Old Testament in the Syriac language discovered in Cave B53 is the oldest of its kind ever found in China.