Advertising The Punch-Line

Advertising The Punch-Line

Joking around in adverts has become a popular way to make money By Yuan Yuan

A Chinese singer who struggled to gain popularity for years has finally made it—as a joke writer, or duanzi shou in Chinese, on social networks. By creating short and funny pieces on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like microblogging service, Xue Zhiqian now has more than 20 million followers and counting.

Originating from Chinese cross-talk, duanzi is defined as a comedic episode, and is often used to refer to short and humorous writing on the Internet. Duanzi emerged as a popular form of posting in the early days of Weibo. Shou is used to refer to people who are good at something.

Weibo users have gradually noticed Xue’s talent for jokes during the past few years, but it was only after he started appearing on TV reality shows in 2015 that he was able to exploit his skills to the fullest.

“Unlike many other pop figures who use acting to be funny, he behaves much more naturally. It’s like he was born to be a hilarious figure,” claimed a netizen after viewing Xue’s performance on TV.

Like many other active joke writers in China, Xue has become a commercial darling, as more and more companies seek to use joke writers to advertise their products. Xue now charges 450,000 yuan ($67,500) for each advertisement and is one of the most expensive joke writers on the market.

“The money I earn by doing this is almost 10 times the amount I could get from being a singer,” said Xue during the Mars Intelligence Agency TV show in May.

Laughing ads style

When Zhang Jianwei quit his job in April 2013, he was already able to gain more from advertising on Weibo than his regular salary. He now asks for more than 100,000 yuan ($15,000) to create an advertisement. He refuses to accept suggestions from clients and doesn’t guarantee that his efforts will produce successful results.

This is quite different from how traditional advertising agencies operate, since they normally cater to a client’s every request.

Here is one typical example of Zhang’s work, created for a smartphone company: A man set up his cat’s paw print as his phone’s password, but found out one morning that his phone was running out of battery. He therefore had to carry the battery charger as well as his cat to the office. Since he was carrying a cat, he was denied access to the subway, mocked by a cabbie, and caused a sensation among his coworkers. At a work meeting, in front of his boss and co-workers, he had to use his cat to unlock the phone and retrieve the PowerPoint document he was going to show.

By inserting simple sketches and cartoons alongside the text, the story has had more than 100 million hits and has been forwarded 170,000 times.

“It may seem that making up such content is easy, since it doesn’t involve much professional skill and the story itself looks like nothing but a brilliant idea in the brain,” Zhang said during an interview with GQ magazine. “This, of course, is not true. I sometimes spend months to come up with an idea, and it is very stressful.”

Ma Ling, famous under her pen name Mi Meng, used to be a journalist and book writer. In 2015, she decided to run her own company but almost failed.

“I lost 4 million yuan ($600,000) in one year,” Ma wrote in an article. “I realized that I was not cut out for business and got back to writing instead.”

She moved her office from Shenzhen in Guangdong Province to Beijing and started all over again. She set up a home page on social networking app WeChat and soon gained millions of followers. “I wrote for fun in the beginning. But as most of my articles are viewed more than 1 million times, some business people have come to me for commercial cooperation,” she said.

Like Zhang, Ma also takes a hardline toward her clients. She doesn’t accept suggestions from clients and refuses to work for brands she is unfamiliar with.

According to Newrank.com, a website that tracks social media in China, Ma’s asking price is 450,000 yuan per advertisement, skyrocketing from the 20,000 yuan ($3,000) she charged for her first piece last year. Despite this, she claimed that she has to reject a number of clients due to the excessive amount of requests she receives.

After she declined work from a computer game company, a senior executive of the company even wrote a 20-page-long letter in an attempt to persuade her to change her mind. “I was moved and said yes in the end,”Ma revealed in an interview with newspaper Beijing Evening News.

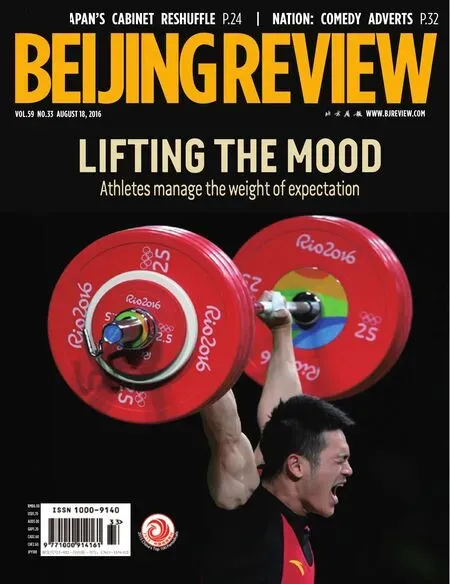

Xue Zhiqian performs during a TV reality show on May 29

Ma’s style is different from Zhang’s though, since her articles are all based on true stories that she’s gathered from friends as well as her own life experience.

Ma writes two stories per workday and publishes an average of two pieces a week. “This is definitely not an easy task,” Ma said. “It is common to stay up in the office.”

Long-term run

The transition from being a joke writer to an advertisement writer has now become more streamlined. In 2011, a blogging account that was simply an aggregation of all kinds of duanzi posted on the Internet could earn 15 million yuan ($2.25 million) per year.

Bai Er, an advertising executive, saw commercial potential in this field. After expanding his network of joke writers, he started to take orders from advertisers and contemporaries. Thus, an early business model for the nascent duanzi industry emerged.

Bai quit his job in 2013 and started a PR company. Yuan Zhuo was among the first joke writers to work with Bai. In 2013 he quit his sales job and set up a company similar to Bai’s and was able to secure some popular writers to work with him.

That same year, Lin Rui, then a 23-year-old fresh college graduate who had met Bai during an internship, established the industry’s third company. Now about 90 percent of full-time joke writers in China work through the three companies, and their combined number of Weibo followers exceeds 300 million, according to a report on GQ.

In March, the three companies held a meeting to discuss the prospects for the duanzi industry. All members were in accord that the business is no longer limited to writing jokes on the Internet. Their commercial value and influence are spreading to other areas like movies, publishing and music.

“If it doesn’t sell, it isn’t creative,” claimed David Ogilvy, one of the founders of Ogilvy & Mather, the world’s leading advertising agency, highlighting the need for creativity in all commercial sectors.

But does this type of advertisement really work? “Many of my clients keep sending me flowers and gifts, since their sales increased largely after I made advertisements for them,” Ma said.

But Xiao Liangshan, a former journalist who works as a social media analyst, pointed out that based on his research, not all clients of joke writers’ advertisements have achieved the results they’ve sought to attain. For example, B&Y’s Home, an interior decoration website in China, only got about 3,000 extra app downloads after spending 300,000 yuan ($45,000) promoting its app through Ma.

“I don’t think that the advertising business of joke writers can go for ever,” said Bai in an interview with GQ. “Now we judge the results of such advertisements largely on the number of views and re-posts, and such figures can be made up or misleading.”

Currently, advertising is still the main source of income for joke writers, but those standing at the top of the pyramid are gradually breaking away from the profession.

Zhang, for example, doesn’t like being called a duanzi shou, since he thinks it is a low-end job. Through his fame and influence, he has now become a partner at an onlineto-offline company.

Lin, too has already begun to move on by setting up subsidiaries to develop new businesses in publishing and moviemaking.

“The era of posting ads on social networking services will end, so the industry needs to break into other fields,” said Lin.

Copyedited by Bryan Michael Galvan

Comments to yuanyuan@bjreview.com