Dynamic monitoring of menopause hormone therapy and defining the cut-off value of endometrial thickness during uterine bleeding

Qiu Sheng, Jun Yang, Qiaoling Zhao, Fen Li,✉

1Center of Maternal and Child Health, First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an, Shaanxi 710061, China;

2Department of Ultrasound, First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an, Shaanxi 710061, China.

Dynamic monitoring of menopause hormone therapy and defining the cut-off value of endometrial thickness during uterine bleeding

Qiu Sheng1, Jun Yang1, Qiaoling Zhao2, Fen Li1,✉

1Center of Maternal and Child Health, First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an, Shaanxi 710061, China;

2Department of Ultrasound, First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an, Shaanxi 710061, China.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of low-dose tibolone therapy on ovarian area, uterine volume and endometrial thickness, and define the cut-off value of endometrial thickness for curettage during uterine bleeding. We followed 619 postmenopausal women, aged 40-60 years, for two years. There were 301 subjects in the low-dose tibolone treatment group and 318 subjects in the control group. The ovarian area, uterine volume and endometrial thickness in all participants were measured by transvaginal ultrasound prior to, one and two years post enrollment, respectively. Endometrial specimens were collected from all subjects with abnormal uterine bleeding during the follow-up period. We found that the uterine volume in the treatment group was greater than that in the control group, and the difference was significant (P<0.05), but there were no significant differences in ovarian area and endometrial thickness between the two groups (P>0.05). When the cut-off value for endometrial thickness was 7.35 mm, the sensitivity and specificity were 100% and 79.07%, respectively, and 85.71% and 93.02% when 7.55 mm was set as the cut-off during tibolone therapy. The results indicate that low-dose tibolone therapy may postpone uterine atrophy and the cut-off value of endometrial thickness may be appropriately adjusted for curettage.

low-dose tibolone, ovarian area, uterine volume, endometrium, dynamic monitoring, cut-off value

Introduction

Longer human lifespan has resulted in an increasingly larger menopausal population with over 100 million women in China estimated to be aged between 45-59 years in 2009[1]. It has been reported that >50% of the women in China, between the ages of 40-59, present with menopause-associated symptoms[2]. Menopause hormone therapy (MHT), also known as hormone replacement therapy (HRT), has been used in China for over 20 years as a major treatment for disorders in periand post-menopausal women[3]. There is a consensus on the timing and guidelines for the use of MHT. In addition to strict adherence to the indications and contraindications of MHT, patients are closely monitored for the potentially harmful side effects of the hormones on target organs. The possible negative side effects may cause fear in patients and even result in discontinuation of the therapy so monitoring and follow-up is of vital importance during treatment.

The influence of MHT on the target organs was different in postmenopausal women due to differences in therapeutic regimen, drug dosage and treatment duration, so results are not consistent[4-7]. Even for identicaltherapy regimens, studies often yielded different results because of physiological differences in subjects[8-11]. Moreover, there was no consensus on an endometrial thickness cut-off value for endometrial curettage to control uterine bleeding during post-menopausal MHT.

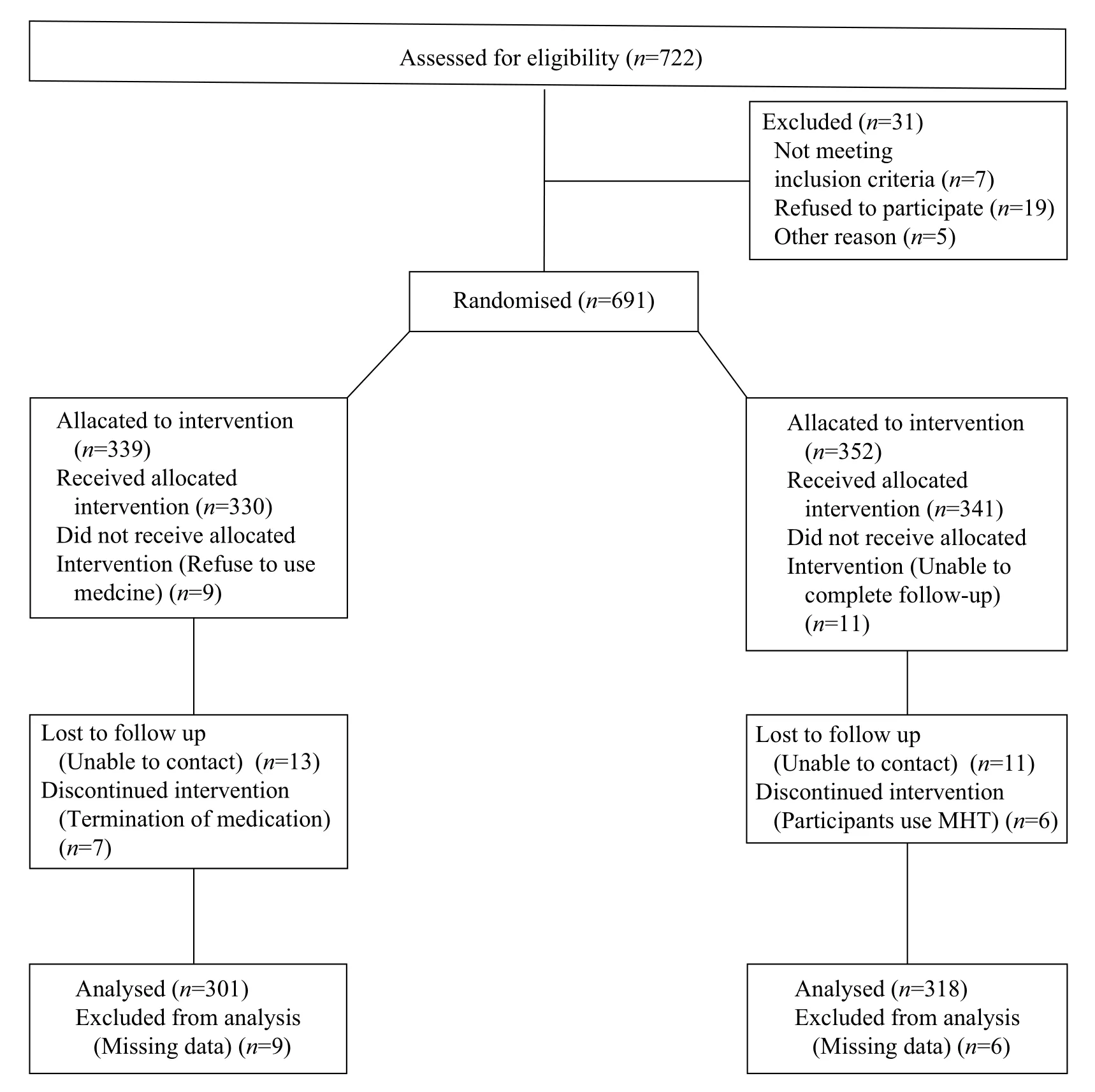

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of the progress of the study.

Tibolone effectively relieves menopause-related symptoms and prevents osteoporosis[12]and is recommended for treating postmenopausal women[13]. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of low dose tibolone therapy on the ovarian area, uterine volume and endometrial thickness by transvaginal ultrasound at three defined intervals, and investigate the optimum cut-off value of endometrial thickness for curettage at uterine bleeding.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

A total of 619 postmenopausal women, aged 40-60 years, who were admitted to the outpatient menopause clinic of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University between June 2009 and June 2013, were enrolled in this prospective study. The subjects were assigned into the tibolone group (1.25 mg once a day) (n=301) and the control group (n=318). The ovarian area, uterine volume and endometrial thickness were measured by transvaginal ultrasound in all participants prior to enrollment, one and two years post enrollment. Endometrial specimens were collected from all patients who experienced abnormal uterine bleeding during follow-up. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) over one-year duration of menopause, serum follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) >40 IU/L, and serum estradiol (E2)<20 pg/mL; (2) development of postmenopausal symptoms; (3) presence of the uterus and bilateral ovary; (4) non-placement or removal of intrauterine device (IUD). Patients who met the following criteria were excluded from the study: (1) previous or current treatment with other sexual hormones; (2) history of coagulopathy or other systemic diseases; (3) development of endometrial disorders or oophoropathy.

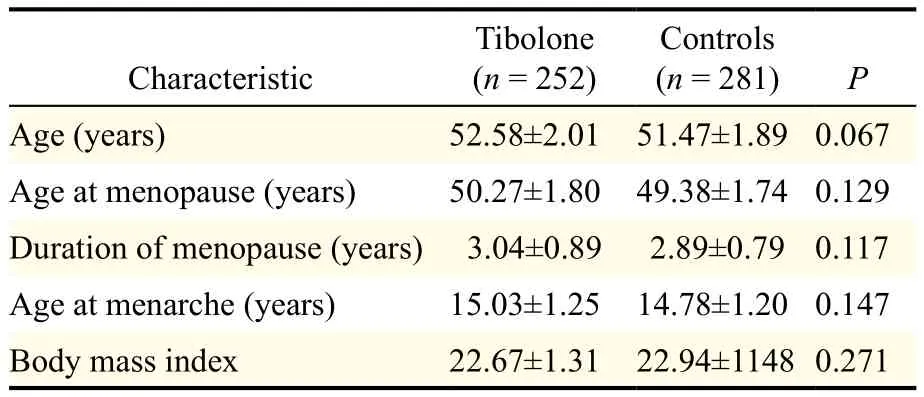

Table 1 Baseline characteristics of the study participants (mean± SD).

Methods

The maximum longitudinal diameter (D1), diameter (D2) and anteroposterior diameter (D3) of the uterus were measured at the standard plane using a Voluson E6 Color Doppler ultrasound diagnostic system with a 7.5-MHz transvaginal transducer (GE Medical Systems; Zipf, Austria). Uterine volume was calculated according to the following formula: Volume (cm3) = 0.5233 (π/6)×D1×D2×D3[14]. The thickness of the anterior and posterior layers of the endometrium was measured in the longitudinal section of each uterus in triplicate, and the mean thickness was estimated. Ovarian longitudinal (d1) and anteroposterior diameters (d2) were measured in the ovaries' maximum longitudinal section; ovarian area was calculated according to the following formula:Area (cm2)=0.785(π/4)×d1×d2[15].

Ethical consideration

This study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University and informed consent with detailed descriptions of the potential benefits and risks of the study was obtained from all participants.

Statistics

All data were entered into Microsoft Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corporation; Redmond, WA, USA), and all statistical analyses were done in the software SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL, USA). Differences of means of the measurement data were tested for statistical significance with Student's t test, with repeated ANOVA test, while chi-square test was employed to compare the difference of proportions. Optimal cut-off value of endometrial thickness was explored by ROC analysis and AUC score. A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

General characteristics

During the follow-up period, pathologic examinations were performed on endometrial specimens collected from subjects with abnormal uterine bleeding. There were 49 in the treatment group and 37 from the control group. Two hundred fifty-two and 281 subjects from the treatment and control group were enrolled in TVS monitoring (Fig. 1). There were no significant differences between the treatment group and control group in age, age at menopause, duration of menopause, age at menarche and body mass index (all P>0.05, Table 1).

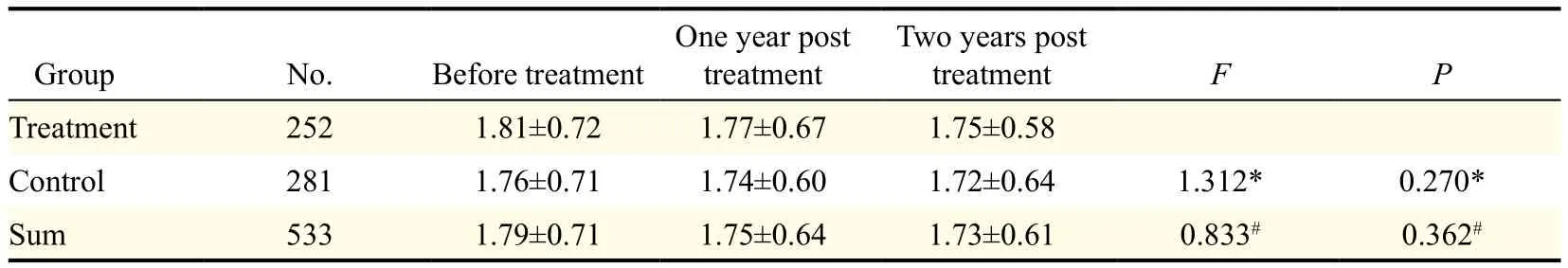

Ovarian area changes

The average ovarian area of patients in the treatment group and the control group is shown in Table 2. There was no statistical difference, between the treatment group and the control group, in the average ovarian area at different time periods (all P>0.05).

Changes in uterine volume

The mean uterine volume of the subjects receiving tibolone did not significantly differ from that measured before treatment (P>0.05). However, there were significant differences in the size of uterine volume between before and after treatment in the control group (P<0.05). There were statistical differences between the tibolone group and the control group in the volume of the uterus; the uterine volumes in the tibolone group were larger than those of the control group in the different measurement periods (P<0.05, Table 3).

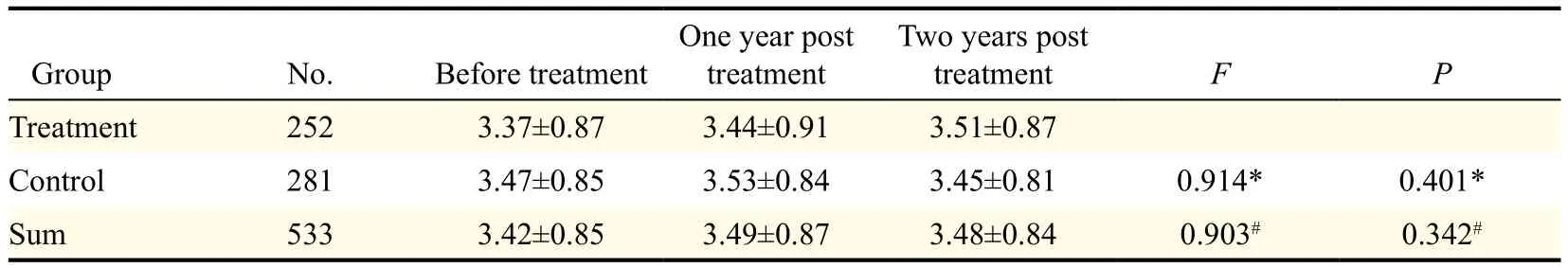

Changes in endometrial thickness

The mean endometrial thickness of patients in the tibolone group and the control group is shown in Table 4.There was no statistical difference between the tibolone group and control group in mean endometrial thickness in the different evaluation periods (P>0.05).

Table 2 Comparison of ovarian area in the treatment and control group (cm2).

Table 3 Comparison of volume of the uterus of the treatment and control group (cm3).

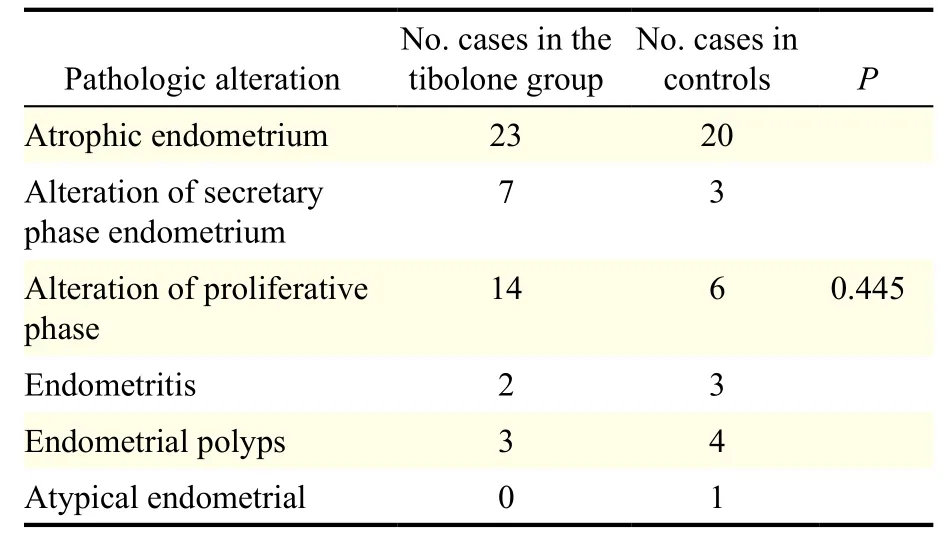

Pathologic characteristics of the endometrium of subjects with abnormal uterine bleeding

Endometrial specimens were collected from 49 and 37 cases in the treatment and control groups, respectively. Pathologic examination of all samples revealed atrophic endometrium, secretary endometrium, proliferative endometrium, endometritis, endometrial polyps and atypical endometrial hyperplasia. No significant difference was found in the constituent ratio of the pathologic alterations of the endometrium between the treatment and control groups (P>0.05, Table 5).

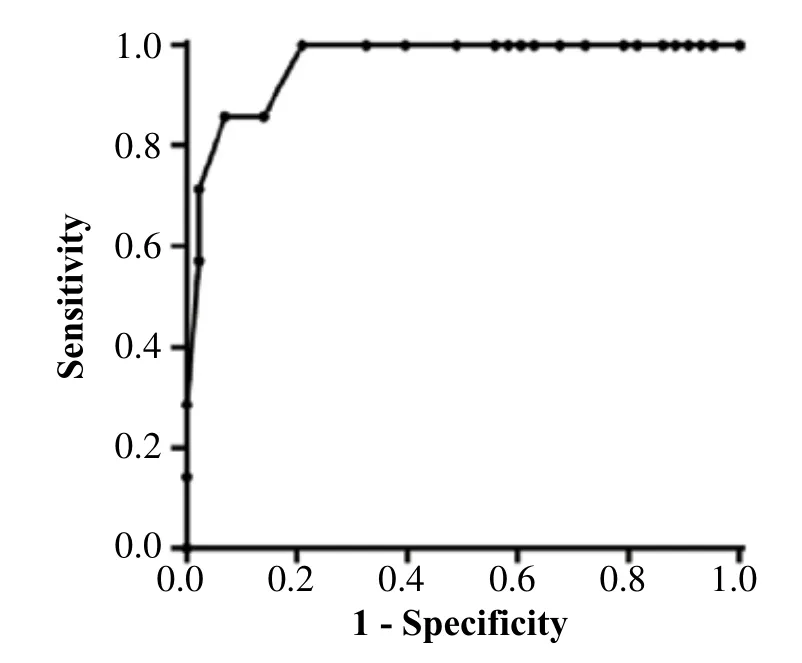

Defining the cut-off value of endometrial thickness during uterine bleeding

When the cut-off value of endometrial thickness was 7.35 mm, the sensitivity and specificity by ROC analysis was 100%, 79.07% and 85.71%, 93.02%, respectively, when the cut-off was set at 7.55 mm (Fig. 2). The AUC score was 0.96, P<0.05.

Discussion

The ovarian volume decreases after menopause. Theoretically, the feedback made by the exogenous hormones has little influence on atrophy. However, researchers found that there were no statistical differences on the volume of bilateral ovaries in the different menopause stages with MHT, and the volume of ovaries decreased without MHT as a result of aging[16-17]. Our research showed that the differences in the ovary area of patients before and after treatment with low-dose tibolone were not significant (P>0.05). Although the volume of the ovary showed no difference after the treatment compared with that before the treatment, the control group also showed no statistical difference during the whole time period. Some researchers thought that the reduction of the area of the ovary to half of its size required a longer period of time (more than 5 years)[18], so extending the follow–up time is needed for further researches.

Existing studies have shown that MHT is related to ovarian tumors[19-20]and is closely related to the length of time it was used. The hazard ratio of ovarian tumors was 1.58[21]for MHT for 5-6 years. For >10 years of MHT, the risk increased slightly[22]and more than 14 years of usage increased the risk ratio to 2.2[23]. In our study, we did not find ovarian malignancy, which indicated that tibolone therapy for two years was safe for the ovary.

A study reported that the uterine volume began to shrink visibly 2 years after menopause and mainly happened in 3-5 years[18]. It has been reported that the volume of the uterus in the treatment group was not statistically different from that of the control group with low level tibolone treatment for the 13-15 months and 12-24 months[4,16]. In our research, the degree of uterine atrophy with the low-dose tibolone treatment was much smaller than that of the control group (P<0.05), suggesting that low-dose tibolone may slow down uterine atrophy, which is not consistent with previous reports[4,16]. The reason for the difference may be related to the study population. Females who went into early menopause were the subjects of our study and their average menopause time was 3.04±0.89 years,which is the critical period of uterine volume contraction[18], and hormone therapy largely affected the volume of the uterus.

Table 4 Comparison of endometrial thickness between the treatment and control group (mm).

Table 5 Pathologic characteristics of patients with abnormal uterine bleeding.

Some studies have shown that short-term tibolone therapy resulted in mild proliferation of the endometrium, which was more remarkable than estrogen-progesterone treatment, while long-term treatment with tibolone led to an atrophic endometrium[9-11]. Another study revealed that postmenopausal women given a low-dose of tibolone for 12 to 24 months were found to have a larger endometrial thickness than those without therapy[4]. Our findings showed that endometrial thickness in patients treated with tibolone at a daily dose of 1.25 mg was similar to that in patients before therapy in the both the treatment and control group (P>0.05). Our results are not entirely consistent with the previous research and this may be associated with different study durations.

A 15% incidence of endometrial polyps was reported within 2 years of tibolone therapy[24]. Histological detection of endometrial specimens collected from women undergoing tibolone treatment revealed that the proportion of changes of proliferative phase endometrium increased and the proportion of atrophic endometrium declined[25]. Another study showed a low prevalenceof endometrial hyperplasia[26]. In the present study, we found that there was no significant difference in the proportion of pathologic alteration of the endometrium at abnormal uterine bleeding between the treatment and control group (P>0.05).

Fig. 2 ROC curve of endome trial thickness and pathologic results.

Meta-analyses recommend 3-5 mm as the cutoff value of endometrial thickness during postmenopausal uterine bleeding[27], while the guidelines of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists defines 5 mm as the cut-off value for endometrial curettage, with a sensitivity of 90% and negative predictive value of 99%[28], which has been widely employed in China. Hanegem and colleagues[29]reported a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 47% when using the 4 mm cut-off value of endometrial thickness, and a sensitivity of 88.6% and a specificity of 90.6% when using 6 mm as the cutoff. It was considered that endometrial curettage was not needed in women who received MHT and had an endometrial thickness of <8 mm due to the effect of exogenous hormones[30]. Our findings showed 100% sensitivity and a specificity of 79.07% when using 7.35 mm as the cutoff value; a sensitivity of 85.71% and a specificity of 93.02% when using the 7.55 mm cut-off value.

In conclusion, the study demonstrates that tibolone therapy for two years does not exert a remarkable effect on ovarian area, endometrial thickness and pathologic alteration during uterine bleeding and it may delay uterine atrophy. An increased cut-off value of endometrial thickness is suggested for curettage if uterine bleeding occurs during tibolone therapy. However, further large-scale, long-term evaluation is required to validate our findings.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the Sci-tech Research Development Program of Shaanxi Province (No. 2015SF015).

References

[1] Ministry of Health (2012): China Statistical Yearbook 2012. (Accessed June 6, 2012 at http://www.moh.gov.cn/ moh wsb wstjxxzx/s7967/201206/55044.shtml.)

[2] Lin SQ. How do the correct application of hormone therapy in postmenopausal women[J]. Chin J Pract Gynecol Obstet (in Chinese), 2011,27(5):321-4.

[3] Baracat EC, Barbosa IC, Giordano MG, et al. A randomized, open-label study of conjugated equine estrogens plus medroxyprogesterone acetate versus Tibolone: effects on symptom control, bleeding pattern, lipid profile and tolerability[J]. Climacteric, 2002,5(1):60-9.

[4] Qu MG. The replacement therapy of long-term low-dose postmenopausal hormone on uterus after menopause[J]. China Med Herald (in Chinese), 2010,7(13):35-6.

[5] Luo T, Han Y, Liu Y. Clinical efficacy of low-dose tibolone in treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis[J].Maternal and Child Health Care of China (in Chinese), 2008,23(23):3284-5.

[6] Wang SH, Lin SQ, Jin MJ, et al. Efficacies of different low-dose regimens of hormone therapy in postmenopausal women[J]. Chin J Pract Gynecol Obstet (in Chinese), 2007,23(3):184-8.

[7] Sun LH, Xu HQ, Chen Y, et al. Comparative study of two hormone replacement therapies during peri-menopausal period[J]. J Clin Med Pract (in Chinese), 2006,10(5):107-8.

[8] Lu JL, Lei XM, Lin SQ, et al. Influence of continuous combined hormone replacement therapy on endometrium--search of optimal regimen[J]. Chin J Med (in Chinese), 2002,37(10):24-6.

[9] Klaassens HA, Heidy VW, Payman HM, et al. Histological and immunohistochemical evaluation of postmenopausal endometrium after 3 weeks of treatment with tibolone, estrogen only, or estrogen plus progestogen[J]. Fertil Steril, 2006,86(2):352-61.

[10] Taboe A, Watt HC, Wad NJ. Endometrial thickness as a test for endometrial cancer in women with postmenopausal vaginal bleeding[J]. Obstet Gynecol, 2002,99(4):663-70.

[11] Levine D, Gosink BB, Johnson LA. Change in endometrial thickness in postmenopausal women undergoing hormone replacement therapy[J]. Radiology, 1995,197:603-8.

[12] Li Y, Yu Q, Ma L, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms and their influence factors during menopausal transition and postmenopause in Beijing city[J]. Maturitas, 2008,61(3):238-42.

[13] Shinde VP, Pudage A, Jangid A, et al. Application of UPLC–MS/MS for separation and quantification of 3α-Hydroxy Tibolone and comparative bioavailability of two Tibolone formulations in healthy volunteers[J]. JPA, 2013,3(4):270-7.

[14] Pirhonen JP, Vuento MH, Makinen JI, et al. Longtime effects of hormone replacement therapy on the uterus and uterine circulation[J]. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 1993,168(2):620-30.

[15] Takahashi K, Yoshino K, Eda Y, et al. Prevalence of polycystic ovaries by transvaginal ultrasound and serum androgens[J]. Int J Fertil, 1992,37(5):290-4.

[16] Xue JQ, Cai JQ, Liu XC. Effect of tibolone on postmenopausal uterus and ovaries atrophy[J]. Prog Obstet Gynecol (in Chinese), 2000,9(1):45-6.

[17] Li N, Jiang YX, GE QS. Observing the effects of longterm and low dose hormone replacement therapy on the uterus, ovary and breasts of postmenopausal women by ultrasonography[J]. J Reprod Med (in Chinese), 2005,14(4):198-203.

[18] Lin SQ, Lin P, Jiang YX, et al. The Shrinkage of Ovarian and Uterine Size and the Decline of Serum Estradiol Level in Post-menopausal Women[J]. Chin J Obstet Gynecol (in Chinese), 1997,32(9):524-6.

[19] Ibeanu O, Modesitt SC, Ducie J, et al. Hormone replacement therapy in gynecologic cancer survivors: Why not? Gynecol Oncol, 2011,122:447-54

[20] King J, Wynne CH, Assersohn L, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and women with premature menopause – A cancer survivorship issue[J]. Eur J Cancer, 2011,47:1623-32

[21] Garnet LA, Howard L, Judd MD, et al. Effects of Estrogen Plus Progestin on Gynecologic Cancers and Associated Diagnostic Procedures[J]. JAMA, 2003,290(13):1739-48.

[22] Garg PP, Kerlikowske K, Subak L, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of epithelial ovarian carcinoma:a meta-analysis[J]. Obstet Gynecol, 1998,92(3):472-9.

[23] Rodriguez C, Patel AV, Calle EE, et al. Estrogen replacement therapy and ovarian cancer mortality in a large prospective study of US women[J]. JAMA, 2001,285(11):1460-5.

[24] Levine D, Gosink BB, Johnson LA. Change in endometrial thickness in postmenopausal women undergoing hormone replacement therapy[J]. Radiology, 1995,197:603-8.

[25] Xue JQ, Kong QY. Histological observation on endometrium following tibolone therapy in postmenopausal women[J]. J Pract Obstet Gynecol, 1999, 15(4):188-9.

[26] Archer DF, Hendrix, S, Ferenczy A, et al. Tibolone histology of the endometrium and breast endpoints study: design of the trial and endometrial histology at baseline in postmenopausal women[J]. Fertil Steril, 2007,88(4):867-78

[27] Breijer MC, Peeters JA, Opmeer BC, et al. Capacity of endometrial thickness measurement to diagnose endometrial carcinoma in asymptomatic postmenopausal women:a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 2012,40(6):62162-9

[28] American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 426: the role of transvaginal ultrasonography in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding[J]. Obstet Gynecol, 2009,113:462-4.

[29] Hanegem N, Breijer MC, Khanc KS, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of the endometrium in postmenopausal bleeding: an evidence-based approach[J]. Maturitas, 2011,68:155-64.

[30] Levine D, Gosink BB, Johnson LA. Change in endometrial thickness in postmenopausal women undergoing hormone replacement therapy[J]. Radiology, 1995,197:603-8.

✉ Fen Li, MD, Center of Maternal and Child Health, First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University, 277 Yanta Western Road, Xi'an, Shaanxi 710061, China. Tel: +86-25-85323223, E-mail: lifen418@126.com.

22 October 2015, Revised 12 December 2015, Accepted 13 January 2016, Epub 10 April 2016

R711.51, Document code: A.

The authors reported no conflict of interest.

THE JOURNAL OF BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH2016年3期

THE JOURNAL OF BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH2016年3期

- THE JOURNAL OF BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH的其它文章

- Lipid transport to avian oocytes and to the developing embryo

- Role of stromal cell-derived factor 1α pathway in bone metastatic prostate cancer

- A pilot exome-wide association study of age-related cataract in Koreans

- Polycystic ovary syndrome patients with high BMl tend to have functional disorders of androgen excess: a prospective study

- Effect of vitamin D3 on production of progesterone in porcine granulosa cells by regulation of steroidogenic enzymes

- Human lgG Fc promotes expression, secretion and immunogenicity of enterovirus 71 VP1 protein