School and community physical activity characteristics and moderate-to-vigorous physical activity among Chinese school-aged children:A multilevel path model analysis

Lijun Wng ,Yn Tng ,b,*,Jiong Luo

a School of Physical Education and Sport Training,Shanghai University of Sport,Shanghai200438,China

b Shanghai Research Center for Physical Fitness and Health of Children and Adolescents,Shanghai University of Sport,Shanghai200438,China

c School of Physical Education,Southwest University,Chongqing 400715,China

1.Introduction

Physical activity(PA)has been considered an important health-enhancing behavior for school-aged children and adolescents.1,2Mounting evidence shows that regular PA in childhood and adolescence improves muscular strength and endurance,reduces cardiovascular disease risk,builds healthy bones and maintains healthy weight,and increases physical and mental wellbeing.3,4However,in addition to various individual factors,5,6motivation to exercise is often influence by social and built environmental factors in schools and around communities.Accordingly,there is an increased interest in understanding contextual factors or correlates that contribute to levels of PA participation in these environmental settings so that appropriate school-and after-school-based interventions to increase PA for children and adolescents can be developed.6-12

While both schools and communities have been shown to provide an important PA promotion venue where children can be taught to adopt and maintain a healthy,active lifestyle,13,14there is little available research in China that examines how these settings affect or influenc children’s levels of PA,which has been shown to be low,15,16especially outside of school.17An early regional study has identifie several factors,such as school environment,access to public facilities in the community,availability of sidewalks and open space near homes,and residential density,that were important in promoting PA among Chinese children and adolescents.18However,additional research is needed in order to understand the extent to which school and community environments may either facilitate or impede the engagement of children in PA in the Mainland of China.

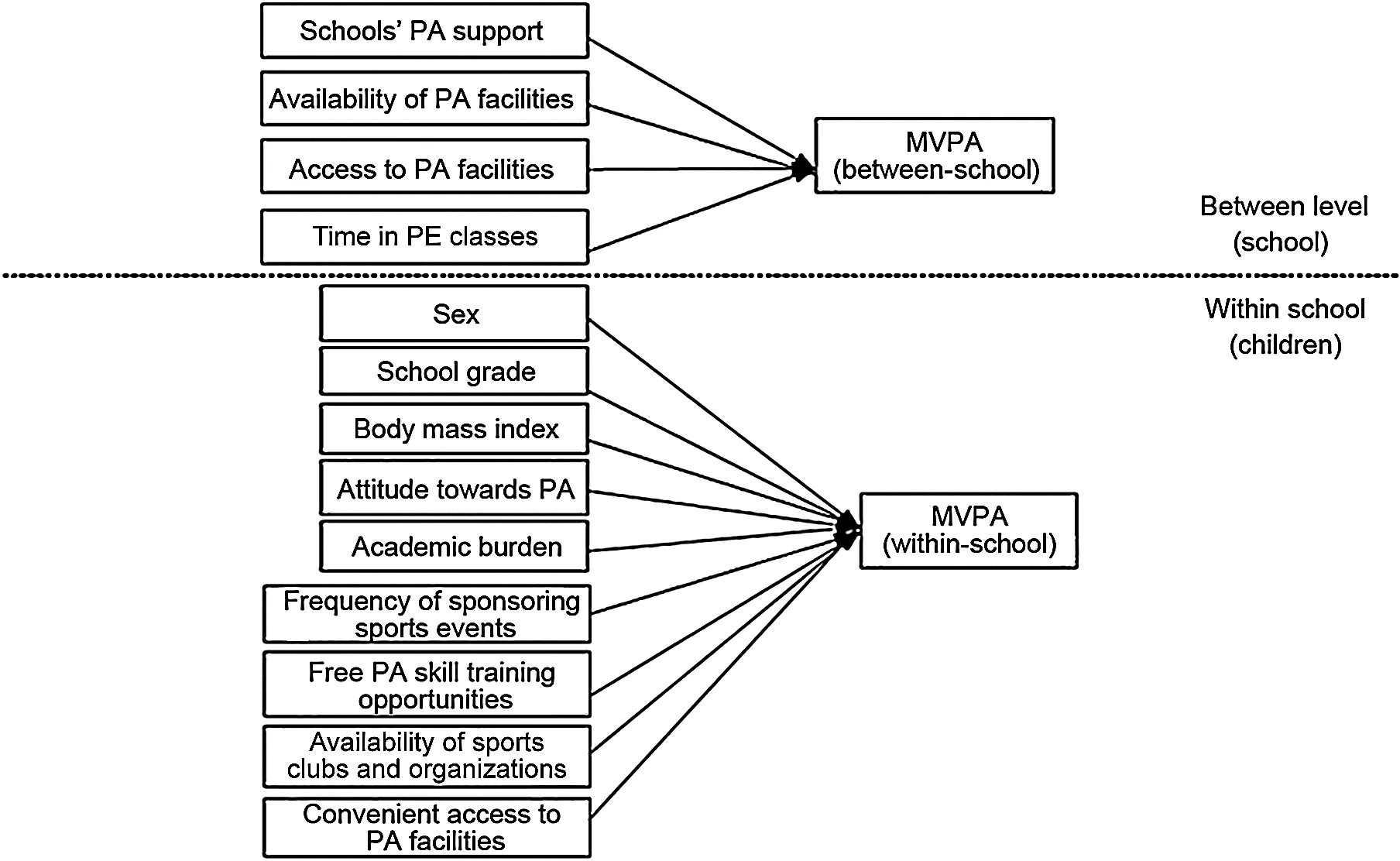

Using a national dataset and a multilevel analysis,we examined the association between school and community PA characteristics and levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity(MVPA)among Chinese school-aged children.On the basis of prior research,6,17we hypothesized that school-level factors,such as PA support,availability of and access to PA facilities,and the duration of school physical education(PE)classes would be associated with MVPA among children and adolescents at the school level,and perceived individual-level community resources factors,such as the frequency of sponsored sports events,PA skill training opportunities,availability of sports clubs and organizations,and convenient access to PA facilities,would be associated with child-level MVPA.

2.Methods

2.1.Study design and participants

Data were extracted from the 2016 Physical Activity and Fitness in China—The Youth Study(PAFCTYS)project,a cross-sectional and nation wide survey of PA and fitnes among Chinese school-aged children.Conducted between October and November 2016,the PAFCTYS involved a stratifie 3-stage cluster sample design to select a representative sample of the Chinese school-aged children population.Details on the study design,methodologies,and research protocol are described elsewhere.19Briefl,a total of 125,281 students,Grades 4–12,from 991(primary(Grades 4–6),junior middle(Grades 7–9),and junior high(Grades10–12))schools in China participated in the survey portion of the PAFCTYS.Children from Grades1 through 3were not included in the survey because of concerns about their cognitive ability to understand and complete the questionnaire items.As part of the study,1 PE teacher from each participating school was also invited to participate.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Shanghai University of Sport.Permission to conduct the study was obtained from principals of each school.Verbal consent was obtained from the children’s parents or guardians and from all participating children and PE teachers prior to data collection.

2.2.Procedures

Following a standardized protocol,trained research staff administered the survey during regular school hours.Some of the students(44.2%)completed the survey online,while the remainder(55.8%)completed a paper version of the survey.The purpose of the study was explained to the PE teachers and students prior to survey administration.Participants were given detailed instructions on how to fil out the survey and were provided ample time for questions.PE teachers completed their surveys individually whereas students completed their surveys as a group in the classroom.

2.3.Measures

The measures used in this study were gathered from the PE teacher and student surveys,which are described in detail below.

2.3.1.MVPA

Children’s self-reported MVPA was assessed by the validated Chinese version20of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form(IPAQ-SF).21The IPAQ-SF questionnaire consists of 4 questions that ask participants to recall aspects of their PA over the previous 7 days,including information on the amount of time(i.e.,number of days and average time per day)spent on sitting,walking,and participating in moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity activities.In the current study,total weekly accumulation of minutes spent on engaging in moderate-intensity and vigorous-intensity activities for at least10min in duration were used as a study outcome variable.

2.3.2.PA measures at the school level

Four subscales were used;each was ascertained from the school PE teachers.Specifical y,teachers were asked about(1)the school principal’s support of PE work(4 items);(2)the availability of school PA facilities(2 items);(3)access to school PA facilities(2 items);and(4)the number of minutes of school PE class time offered weekly(2 items).The items about principal support included queries on the provision of PE staff,professional training of PE teachers,remuneration,and fin an cial support for PE.The response to each item was anchored on a5-pointscale,ranging from 1(strongly disagree)to5(strongly agree).Availability of school PA facilities was measured by whether the teachers were satisfie that the PA facilities met the needs of PE teaching and extracurricular PA by students.Access to school PA facilities was measured by whether school PA facilities were open at no cost to students on weekends and holidays.Items in each of these2 subscales were anchored to a 3-point scale,ranging from 1(not satisfie)to 3(completely satisfie)for avail ability of school PA facilities,and from 1(not open)to 3(open all day)for access to school PA facilities.Finally,the amount of PE class time was measured by responses to 2 items regarding the number of 30–45m in PE classes and 60–90m in PE classes offered each week.The overall minutes of PE class time per week were calculated by multiplying the number of classes taught by the number of class minutes per week.Scores from these 4 subscales were aggregated from individual teacher responses,with higher scores indicating favorable school-level PA environments.

2.3.3.PA resource measures in communities

Children were asked to respond to a series of survey questions about PA resources in their neighborhood communities.These included 4 single-item scales:(1)frequency of sponsoring sports events;(2)convenient access to PA facilities;(3)free PA skill training opportunities;and(4)availability of sports clubs and organizations.Convenient access to PA facilities and availability of sports clubs and organizations were measured using a 2-pointscale(no or yes),and the remaining 2measures were assessed using a 5-pointscale,ranging from 1(none)to 5(much),with high scores on each of these measures indicating favorable community PA resources.A 2-week interval test–retest reliability was assessed by the intra class correlation coefficien(ICC)on 270 children in Grades 5,8,and 11,with a coefficien of 0.51 for the single-item community’s frequency of sponsoring sports events scale and 0.47 for the free PA skill training opportunities scale.

2.3.4.Attitude toward PA and academic burden

These 2 measures were used as control variables in the structural path model evaluated(see the section“Statistical analysis”for details).Attitude toward PA was measured by the question regarding children’s attitude toward PA participation in the future with responses recorded on a 5-point scale,ranging from 1(no plan to exercise)to 5(keeping physically active everyday).Academic burden was assessed by a single question:“How pressured do you feel by the schoolwork you have to do?”22with responses being recorded on a 5-point scale,ranging from 1(not at all)to 5(a lot).Test–retest reliabilities of these 2 scales,as measured by ICC,were 0.64 for attitude toward PA and 0.53 for academic burden.

2.3.5.Demographic information

Demographic information was obtained from the children’s survey.This information included age,school grade(primary,junior middle,or junior high school),sex,height,and weight.Children’s height and weight were measured objectively by a portable instrument(GMCS-IV;Jianmin,Beijing,China).

Their body mass index(BM I)was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters(kg/m2).

2.4.Statistical analysis

Data were preliminarily analyzed using SPSS(Version 21.0;IBM Corp.,Armonk,NY,USA)to check for data normality and to conduct a descriptive analysis of the study variables.A list wise deletion approach(complete-case analysis)was used.Given the multilevel structure of the PAFCTYS data,a multilevel path analysis was used to analyze the 2-level model shown in Fig.1,in which all variables across between-parts and within-parts of the model were observed or manifested.As shown,the model was specifie on the 2 levels of the data hierarchy(i.e.,student-level data,school-level data)in the PAFCTYS.School-level variation in MVPA was assessed by calculating the ICC(intra school)and design effects(define as 1+(average class size–1)×ICC).23This correlation describes the degree of similarity among students of the same school on MVPA and is define as a ratio of(between-school variability)/(between-school variability+within-school variability).

For the between-school part of the model(with as ample size of 935 schools),MVPA was regressed on 4 school-level exogenous variables.In the within-school part of the model(with a sample size of 80,928 students), student-level MVPA was regressed on the5 individual variables(i.e.,school grades,sex,BM I,attitude toward PA,academic burden)and 4 variables measuring children’s perceived PA resources in communities.

Fig.1.Hypothesized path model examining associations between school and community PA characteristics and MVPA among Chinese school-aged children.MVPA=moderate-to-vigorous physical activity;PA=physical activity.

The multilevel path model was tested using the M plus24structural equation modeling software,which allows estimation of multilevel models that contain random variation in intercepts and between-group regression slopes(i.e.,a regression with random coefficients while adjusting for clustering due to the complex sampling of the PAFCTYS.A maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors was used to generate the estimates of the model’s parameters.Goodness-of-fi of the hypothesized model was evaluated using the χ2statistic and root mean square error of approximation,with values of0.06 or less indicating an acceptable level of fit25Both standardized and unstandardized regression coefficient are reported.Estimates with a p value of≤0.05(2-tailed)are interpreted as statistically significant

In an exploratory mode,we examined urban–rural differences in the structural relationships under scrutiny.We used a multi group approach in which we started an unconstrained model(M0,i.e.,no urban–rural cross-group equality constraints on the structural regression paths)followed by a series of increasingly constrained models(i.e.,constraining the structural paths of interest across the urban and rural groups to be equal:M1-8).Differences between each of the constrained and unconstrained(nested)models(e.g.,M0and M1)were tested by calculating the difference between the χ2statistic(Δχ2)for the 2models under comparison.

3.Results

3.1.Preliminary analysis

An initial inspection of the raw data showed that 33 schools(3%;4711 children)did not have the school-level information relevant to this study,and 39,642 children(32%)had either missing individual data or provided data that were out of normal range.These children(n=39,642)and the schools they attended(n=23)were subsequently removed.Removal of the missing and outliers’data resulted in a total of 935 schools(94%)and 80,928 children(65%)that were included in the current analyses.The average number of children in each school was 87 children.

Descriptive statistics for the study population of children and the outcome measures for the total sample(also segmented by residence locale)are presented in Table 1.The children in the study were equally distributed in terms of sex(50.9%girls)and school grades(primary,junior middle,and junior high schools),and had an age of 13.71±2.94 years old.The MVPA among the participating children was 52.34±50.58m in/day(366±346m in/week).

A bivariate correlation matrix including all observed variables in the structural path model is shown in Table S1 in the online supplement.An ICC value of 0.08 was estimated in the school MVPA,indicating a small,but possibly important,8%variation at the school level,with a strong design effect of 7.9,calculated by 1+(87–1)×0.08.Both the ICC and the design effect provided justificatio for a multilevel path analysis.

3.2.Relationships between school and community factors and MVPA

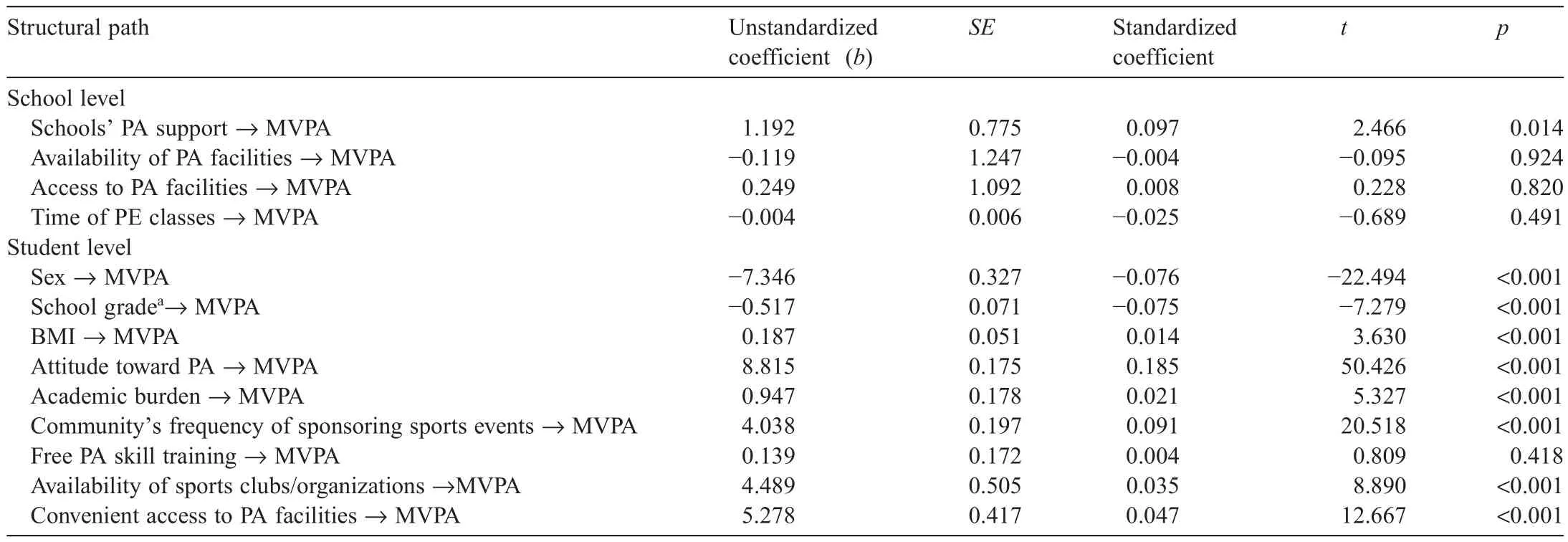

The path model estimated using the total sample(935 schools,80,982 children)resulted in a χ2of11,389.61(df=40,p<0.001)with an acceptable fi as judged by 0.068 in rootmean square error of approximation.Table 2 shows parameter estimates generated from the multilevel path model.At the school level,an inspection of the path coefficient indicates that school PA support was the only variable that was significant y(p=0.014)related to high levels of school-level MVPA(b=1.192,where b is the unstandardized path coefficient)None of the remaining 3 factors was significant y related to school-level MVPA in children.

Table1 Descriptive statistics of the study population—the 2016 Physical Activity and Fitness in China—The Youth Study.

At the student level,results indicate that children who reported high scores on frequency of community-sponsored sports events(b=4.038,p<0.001),availability of sports clubs and organizations(b=4.489,p<0.001),and convenient access to PA facilities(b=5.278,p<0.001)were significant y more likely to report high levels of MVPA.Free PA skill training was not significant y related(p=0.418)to the children’s MVPA.Inaddition to these perceived community factors by children,boys(b=–7.346,p<0.001)and children who were in the lower school grades(b=–0.517,p<0.001),who had higher BM I(b=0.187,p<0.001)and highly positive attitudes toward PA(b=8.815,p<0.001),were significant y and positively related to high levels of within-school MVPA.Children who reported experiencing a heavy academic burden were significant y related to high levels of within-school MVPA(b=0.947,p<0.001)(Table 2).

Table2 Parameter estimates of the multilevel path model.

Overall,the school-level variables jointly accounted for 1%of the between-school variation in MVPA,whereas the individual-level variables jointly accounted for about9%of the within-school variation in MVPA.

3.3.Urban and rural differences

Details of model testing statistics are shown in Table S2 in the online supplement.Differences in χ2statistics show that the path from availability of PA facilities to MVPA varied across urban and rural samples(Δχ2=5.749, Δdf=1,p=0.016).Specifical y,compared with those living in rural areas(b=0.29,p=0.6),availability of PA facilities was significant y related to decreased levels of MVPA among children living in urban areas(b=−1.744,p=0.004).None of the remaining paths in the model was found to be significan in regard to urban versus ruralareas.

4.Discussion

In this study of the PAFCTYS data,we show that PA support from school administrators was significant y associated with an increased level of school children’s participation in MVPA.None of the other school-level factors(the avail ability of school PA facilities,access to school PA facilities,weekly school PE class time)were found to be related to school-level MVPA.However,across urban–rural settings,availability of school PA facilities was significant y but inversely related to school-level MVPA among urban children.At the individual level,children’s perceptions of the frequency of community-sponsored sports events,availability of clubs and organizations,and convenient access to PA facilities were found to be associated with a high level of MVPA participation.

Within a multilevel modeling framework,this is the firs study that examined the influenc of school-level factors on MVPA of Chinese school-aged children.We show that,among several factors examined, PA support from the school principals was the only factor positively associated with school children’s MVPA participation.This findin is consistent with another report in the United States that students’perceptions of being supported for PA at school was related to adolescents participating in more PA,26which suggests the importance of the role that school plays in promoting school-level MVPA among Chinese school-aged children.

Unlike the finding reported elsewhere,10our hypotheses regarding the influenc of the availability of PA facilities,access to those facilities,and the duration of school PE classes on overall school-level MVPA were not supported.Notably though,when urban–rural differences were explored,the findings show that the availability of school facilities for PA was negatively related to MVPA among children living in urban areas.Although limited availability of recreational facilities creates barriers to PA,26finding from this study suggest that availability of PA facilities at urban schools were associated with low levels of MVPA among school students.One speculation may be that the overemphasis of and high expectations for academic performance and achievement in urban elite schools27may have made led to underutilization of the PA facilities in urban schools,thus impeding school-wide PA promotion.

The failure to show significan differences related to other school-level factors in this study suggests that there may be limited utility in our use of subjective measures for effectively capturing MVPA variation among schools and school children.Self-reports such as those used in our study are subject to response biases(e.g.,socially desirable reporting).Future studies should incorporate objectively measured school-level factors,including policies related to the actual availability of PA facilities,assessments resulting from direct fiel observations,assessments of availability that are audited or generated by geographic information systems,and factors related to access to and use of play areas,sports fields and sports facilities.

At the level of children,our results indicate the importance of children’s perceptions of their immediate community’s(neighborhood’s)PA-related resources in either facilitating or maximizing their MVPA participation.These finding are consistent with those reported in the current literature,which shows that use of community-based facilities,28availability of PA facilities near school areas,29and accessibility to sports and PA equipment30were associated with active participation in PA among children.

Interestingly,children in our study who perceived a high burden of academic pressure reported high levels of MVPA,a findin that is contrary to those reported in other studies in which academic pressure was seen as a barrier for participation in PA.31,32Although the reasons underlying this counterintuitive find in are not clear,it may be that in the highly academic focused culture of China,children see their participation in MVPA as a coping mechanism to combat the heavy academic burden and pressure.Future studies should examine the potential mechanisms that mediate the academic burden and PA relationship.

A strength of this study is that it provides the firs attempt aimed at delineating variation in MVPA at the school level and at the child level.This type of multilevel analysis approach is underutilized,especially in China,but it is important because it allows us to examine the potential impact of school support and school policies on promoting PA in schools,which can in turn lead to the development and implementation of school-level policies and initiatives aimed at increasing multilevel(e.g.,school level,community level,or a combination of both)PA interventions and promotion programs among school-aged children.

Interpretation of the results from this study should be made with caution due to a few inherent limitations.First,the cross sectional data preclude any causal inference from being made on the observed structural relationships.Second,a significan number of study children(35%)were excluded due to missing data or non-normality problems in the data.Our list wise approach for handling missing and non-normality data,therefore,threatens the generalizability of the finding to larger Chinese school-aged populations.A third limitation is that all study measures were based on self-reports,which are known to produce recall or response biases.For example,children and youths have been found to overestimate their PA when compared to measurements made through the use of objective measures such as accelerometers.20,33Similarly,the use of teachers’self-reports on school PA support may have reduced the objectivity of measuring support at schools,which may in turn have led to the statistical in significanc of many of the school level results,which might yield a less robust model that explained only 1%of school-level variation.Last but not least,our data were unable to delineate children’s MVPA in schools,in after-school periods,or in communities.Therefore,specifi influence of school-or community-related factors on MVPA among Chinese school-aged children remain unknown and require future investigation.

In conclusion,finding from this study indicate that school support for PA and availability of and access to community PA resources are associated with school-level and individual-level MVPA participation among Chinese school-aged children.Our finding also indicate that school PA facilities appear to be underutilized at urban schools,where low levels of MVPA among school children were observed.Taken together,our findings suggest that strengthening policies on PA support at school and maximizing PA resources and opportunities in school environments and communities may help promote PA in school aged children in the Mainland of China.

Acknowledgment

This work is supported by the Key Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China(No.16ZDA227).

Authors’contributions

LW participated in the data analysis and drafted the manuscript;YT conceived of the study,participated in its design and coordination,and helped to draft the manuscript;JL performed the statistical analysis and helped to interpret the data.A ll authors have read and approved the fin a version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix:Supplementary material

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2017.09.001

1.U.S.Department of Health and Human Services.Physical activity guidelines advisory committee report.Washington,DC:U.S.Department of Health and Human Services;2008.

2.World Health Organization.Physical activity and young people—Recommended levels of physical activity for children aged 5–17 years.Available at:http://www.who.int/dietphysical activity/factsheet_young_people/en;2015[accessed 26.07.2017].

3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical activity facts.Available at:https://www.cdc.gov/healthyschools/physical activity/facts.htm;2014[accessed 26.07.2017].

4.Janssen I,LeBlanc AG.Systematic review of the health benefit of physical activity and fitnes in school-aged children and youth.Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act2010;7:40.doi:10.1186/1479-5868-7-40

5.Sterdt E,Liersch S,Walter U.Correlates of physical activity of children and adolescents:a systematic review of reviews.Health Educ J 2014;73:72–89.

6.Lu C,Stolk R,Sauer P,Sijtsma A,Wiersma R,Huang G,et al.Factors of physical activity among Chinese children and adolescents:a systematic review.Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2017;14:36.doi:10.1186/s12966-017-0486-y

7.Haerens L,Craeynest M,Deforche B,Maes L,Cardon G,Bourdeaudhuij I.The contribution of home,neighborhood and school environmental factors in explaining physical activity among adolescents.JEnvir Public Health 2009;2009:320372.doi:10.1155/2009/320372

8.Machado de Rezende LF,Machado Azeredo C,Sliva KS,Claro RM,França-Junior I,Tourinho Peres MF,et al.The role of school environment in physical activity among Brazilian adolescents. PLoS One 2015;10:e0131342.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0131342

9.McGrath LJ,Hopkins WG,Hinckson EA.Associations of objectively measured built-environment attributes with youth moderate-vigorous physical activity:a systematic review and meta-analysis.Sports Med 2015;45:841–65.

10.Morton K,Atkin A,Corder K,Suhrcke M,van Sluijs E.The school environment and adolescent physical activity and sedentary behavior:a mixed-studies systematic review.Obes Rev 2016;12:142–58.

11.Remmers T,Van Kann D,Thijs C,de Vries S,Kremers S.Playability of school-environments and after-school physical activity among 8–11 year-old children:specificit of time and place.Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016;13:82.doi:10.1186/s12966-016-0407-5

12.Mears R,Jago R.Effectiveness of after-school interventions at increasing moderate-to-vigorous physical activity levels in 5-to 18-year olds:asystematic review and meta-analysis.Br J Sports Med 2016;pii:bjsports-2015-094976.doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-094976

13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth physical activity: the role of schools.Available at:https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/physical activity/toolkit/factsheet_pa_guidelines_schools.pdf;2011[accessed 27.07.2017].

14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Youth physical activity:the role of communities.Available at:https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/physical activity/toolkit/factsheet_pa_guidelines_communities.pdf; 2009[accessed 27.07.2017].

15.Zhang X,Song Y,Yang TB,Zhang B,Dong B,Ma J.Analysis of current situation of physical activity and influencin factors in Chinese primary and middle school students in 2010.Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi2012;46:781–8.[in Chinese].

16.Liu Y,Tang Y,Cao ZB,Chen PJ,Zhang JL,Zhu Z,et al.Results from Shanghai’s(China)2016 Report Card on Physical Activity for Children and Youth.J Phys Act Health 2016;13(Suppl.2):S124–8.

17.Tudor-Locke C,Ainsworth BE,Adair LS,Du S,Popkin BM.Physical activity and inactivity in Chinese school-aged youth:the China Health and Nutrition Survey.Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2003;27:1093–9.

18.LiM,Dibley M,Sibbritt D,Yan H.Factors associated with adolescents’physical inactivity in Xi’an,China.Med Sci Sports Exerc 2006;38:2075–85.

19.Fan X,Cao ZB.Physical activity among Chinese school-aged children:national prevalence estimates from the 2016 Physical Activity and Fitness in China—The Youth Study.J Sports Health Sci 2017;6:388–94.

20.Wang C,Chen P,Zhuang J.Validity and reliability of international physical activity questionnaire-short form in Chinese youth.Res Q Exerc Sport 2013;84(Suppl.2):S80–6.

21.Craig CL,Marshall AL,Sjostrom M,Bauman A,Booth ML,Ainsworth BE,et al.International physical activity questionnaire:12-country reliability and validity.Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:1381–95.

22.Lemma P,Borraccino A,Berchialla P,Dalmasso P,Charrier L,Vieno A,et al.Well-being in 15-year-old adolescents:a matter of relationship with school.J Public Health 2015;37:573–80.

23.Kish L.Survey sampling.New York,NY:Wiley;1965.

24.Muthén LK,Muthén BO.Mplus user’s guide.8th ed.Los Angeles,CA:Muthén&Muthén;1998–2017.

25.Hu L,Bentler PM.Cutoff criteria for fi indexes in covariance structure analysis:conventional criteria versus new alternatives.Struct Equ Modeling 1999;6:1–55.

26.Findholt NE,Michael Y,Davis MM,Brogoitti VW.Environmental influence on children’s physical activity and diets in rural Oregon:results of a youth photovoice project.J Rural Nurs Health Care 2010;10:11–20.

27.You Y.A deep reflectio on the“key school system”in basic education in China.Front Educ China 2007;2:229–39.

28.Babey SH,Wolstein J,Diamant AL.Adolescent physical activity:role of school support,role models,and social participation in racial and income disparities.Environ Behav 2016;48:172–91.

29.Matisziw TC,Nilon CH,Wilhelm Stanis SA,LeMaster JW,McElroy JA,Sayers SP.The right space at the right time:the relationship between children’s physical activity and land use/land cover.Landsc Urban Plan 2016;151:21–32.

30.Sallis JF,Conway TL,Prochaska JJ,McKenzie TL,Marshall SJ,Brown M.The association of school environments with youth physical activity.Am J Public Health 2001;91:618–20.

31.Haugland S,Wold B,Torsheim T.Relieving the pressure?The role of physical activity in the relationship between school-related stress and adolescent health.Res Q Exerc Sport2003;74:127–35.

32.Rajaraman D,Correa N,Punthakee Z,Lear S,Jayachitra K,Vaz MS.Perceived benefits facilitators,disadvantages,and barriers for physical activity amongst South Asian adolescents in India and Canada.J Phys Act Health 2015;12:931–41.

33.Long C,Brand S,Feldmeth A,Holsboer-Trachsler E,Pühse U,Gerber M.Increased self-reported and objectively assessed physical activity predict sleep quality among adolescents.Physiol Behav 2013;120:46–53.

Journal of Sport and Health Science2017年4期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2017年4期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- The Wingate anaerobic test cannot be used for the evaluation of grow th hormone secretion in children with short stature

- The effects of aerobic exercise training on oxidant-antioxidant balance, neurotrophic factor levels, and blood-brain barrier function in obese and non-obese men

- Correlates of long-term physical activity adherence in women

- Empowering youth sport environments:Implications for daily moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and adiposity

- Prevalence of physical fitnes in Chinese school-aged children:Findings from the 2016 Physical Activity and Fitness in China—The Youth Study

- Overweight,obesity,and screen-time viewing among Chinese school-aged children:National prevalence estimates from the 2016 Physical Activity and Fitness in China—The Youth Study