Pharmacokinetics of Milbemycin Oxime in Dogs Following Its Intravenous and Oral Administration

Lu Yi-tong, Qi Lian-wen, Xu Qian-qian, Ding Liang-jun Wang Bo Liu Hai-rui and Li Ji-chang*

1 State Key Laboratory of Natural Medicines, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, China

2 College of Veterinary Medicine, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin 150030, China

3 Shandong Binzhou Animal Science and Veterinary Medicine Academy, Binzhou 256600, Shandong, China

Introduction

Milbemycin oxime is a member of macrolide antiparasitic antibiotics produced through fermentation byStreptomyces hygroscopicussubspeciesaureolacrimosus(Takiguchiet al., 1980; Okazakiet al.,1983), which consists of a mixture of milbemycin A3oxime and milbemycin A4oxime at a 20: 80 ratio (Bater, 1989), and is used as a feline and canine anthelmintic agent.It has been shown to be highly effective at a recommended dosage of 0.25-1.0 mg · kg-1against canine heartworm (Guerreroet al., 2002; Genchiet al., 2004) and various parasitic nematodes e.g.Toxocara canis,Ancylostoma caninum,Trichuris vulpis,Spirocerca lupi,Thelazia callipaedain cats (Humbert-Drozet al., 2004; Schenkeret al.,2007) and dogs (Bowmanet al., 2005; Schenkeret al., 2006; Ferroglioet al., 2008; Kellyet al., 2008;Koket al., 2010; 2011), as well as against generalized demodicosis in dogs at 0.75-2 mg · kg-1orally every 24 h for 1-6 months (Scottet al., 2001; Holm, 2003).

The closely related chemical structure to milbemycins and avermectins (Shoopet al., 1995;Mckellaret al., 1996) leads to insecticidal activities for milbemycin oxime against important pests,as has been found for ivermectin, abamectin and emamectin.Currently, the widely accepted mode of action of macrolide antiparasitic drugs is to open the glutamate-gated chloride ion channels, which is phylogenetically related with GABAA receptor/channel present in the musculature of invertebrates,but not in vertebrates (Wolstenholme and Rogers,2005; Wolstenholme, 2010), thus resulting in a unrestricted slow release of chloride ions into the postsynaptic neuron to prevent initiation of action potentials in the parasite neuromusculature leading to flaccid paralysis and death (Mckellar and Jackson,2004; Beech, 2010).Activity of the transmembrane P-glycoprotein is mainly responsible for the lack of toxicity in mammals, which can reduce tissue distribution and bioavailability, and enhance the elimination of macrocyclic lactones, whereas those mammalian species sensitive to drugs present a deficient expression of P-glycoprotein showing greater bioavailability after oral administration and higher levels of drugs in their central nervous system tissue(Edwards, 2003; Danaheret al., 2006).

Although oral administration of milbemycin oxime has been used for a long time, knowledge of its pharmacology is still extremely limited.There is not enough pharmacokinetic data available in the literature supporting the current oral dosage regimens of milbemycin oxime in dogs.The objective of this study was to investigate the plasma pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of milbemycin oxime in dogs, after its oral administration formulated as tablets at three single doses of 0.25, 0.5 and 1.0 mg · kg-1, respectively referred to the commended dose of the commercial milbemycin A tablets (Meguro chemical Industry Co.,Ltd., Japan).Plasma milbemycin oxime concentrations were measured by LC-MS/MS.Data generated in the present work would help to optimize the efficacy of current antiparasitic regimens and to delay the emergence of resistance.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All the experiments were performed with dogs in accordance with Heilongjiang Regulations for the Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals and approved by Heilongjiang Animal Care and Use Committee, Harbin, China.A total of 24 pure-bred beagle dogs were purchased from Tumor Hospital in Heilongjiang Province (Harbin, China),ageing 9-11 months old, weighing 8-12 kg and having no history of any antiparasitic medications in the previous three months.They were put in separated stainless-steel cages and fed with appropriate quantity of non-medicated commercial dog foods composed of carbohydrate, protein, vitamin, fat and mineral elements from Royal Canin (Crown Pet Foods Ltd.,France) twice daily and tap water from drinking nipplesad libitum, with the light/dark cycle 12/12.An acclimation period of one week was observed prior to initiation of the trial.

Pharmacokinetic experiment

Animals were randomly allocated into four groups,and each consisted of six dogs (three males and three females).Milbemycin oxime tablets were ground coarsely, folded in a small piece of ham to camou flage the drug, and orally administered to three groups of dogs which were fasted overnight before dosing at doses of 0.25, 0.5 and 1.0 mg · kg-1body weight(BW), respectively.All the animals received their first fedding 4 h after drug administration.Heparinized blood samples (3-5 mL) were collected by limb vein prior to administration then at 30, 60 and 90 min and 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24, 36 and 48 h after dosing.The fourth group received milbemycin oxime IV,which (>98% purity, Zhejiang Hisun Pharmaceutical,China) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO),diluted 20-fold in 25% hydroxypropyl-βcyclodextrin(HPBCD), and dosed at 0.5 mg · kg-1BW in the small saphenous vein of the hind limbs.Heparinized(1 U · μL-1) blood samples (3-5 mL) were collected prior to drug administration and at 10, 15, 20, 30,45 and 60 min and 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 h thereafter.Blood samples of all the experimental groups were centrifuged (1 000 g for 10 min) immediately.Plasma was collected and stored at –20℃ pending the assay.

Sample preparation and LC-MS/MS analysis

A 4 mL volume of acetonitrile and 0.3 g of sodium chloride were added to centrifugal tubes containing 1 mL of plasma samples.After gentle agitation in a rotating mixer for 3 min and centrifugation at 3 000 g for 5 min, the supernatants were transferred to new centrifuge tube and evaporated to dryness under a nitrogen stream at 50℃.The dry residues were reconstituted with 3 mL of a mixture of methanolammonium acetate (5 mmol · L-1) (10 : 90; v/v).The reconstituted samples were passed through C18cartridges (Sep-Pak C18, 100 mg; Waters, Milford,Mass.), which were pre-conditioned with methanol(3 mL) and water (3 mL; Milli_Q ultrapure water system, Merck Millipore Company, USA).After samples were passed through, the cartridges were washed with 3 mL of a mixture of methanolammonium acetate (5 mmol · L-1) (10 : 90; v/v).Elutions (methanol 3 mL) were collected into plastic test tubes and evaporated to dryness under a nitrogen atmosphere at 50℃.Dry residues were solubilised in 1 mL of mobile phase composed of acetonitrileammonium acetate (5 mmol · L-1) in a proportion of 85 : 15 (v/v) and filtered through a 0.22 µm nylon syringe filters (Lubitech Technologies Limited,Shanghai, China).Aliquots of 5 µL were injected into LC-MS/MS system (TSQ Quantum, Finnigan, San Jose, CA, USA).

LC-MS/MS analysis

Concentrations of milbemycin oxime in plasma were determined by a sensitive LC-MS/MS method developed in our laboratory.LC-MS/MS system consisted of a Finnigan Surveyor LC pump, a Surveyor AS 100-well automatic sampler, an electrospray ionization source and a three-pole tandem mass spectrum.It was operated in electrospray ionization(ESI) mode under the following conditions: highpurity nitrogen (>99%) was used as the nebulizing gas at a pressure of 49 psi (1 psi=56 894.78 Pa),and argon as the collision gas at a pressure of 20 psi for tandem mass spectrometry.The capillary temperature was maintained constant at 300℃, and the spray potential of ESI interface was set at 4.8 kV.The molecular ion was selected at m/z 536.Chromatographic separation was performed on a WAT044375 HPLC column (steel, 5-μm-particlesize C18, 250 mm×4.6 mm; Waters, USA) with a mobile phase of acetonitrile-ammonium acetate(0.5 mmol · L-1, 85 : 15, v/v) pumped at 1 mL · min-1.Under these conditions, the retention times of milbemycin A3and A4oxime were 4.9 and 5.6 min,respectively.To examine the linearity of the detector response, a plasma calibration line with the following standard's concentrations: 0, 5, 10, 50, 100, 150, 200 and 500 ng · mL-1was prepared and assayed.The curve drawn by the comparison of peak areas with the plasma drug concentrations of the samples was determined to be linear in the concentration range of 5 500 ng · mL-1, and its regression equation wasy=94.2379x–60.4477 withr=0.9996.The limit of quantitation (LOQ) was 5 ng · mL-1.

Analysis of independently prepared quality-control plasma samples (5, 150 and 400 ng · mL-1) indicated good precision because of the inter-day accuracies of 1.44%, 3.73% and 5.80% and the intra-day accuracies of 3.32%, 4.59% and 7.10%, respectively.The recovery rates of milbemycin oxime in dog plasma were 87.5±6.1%, 86.4±7.9% and 95.4±13.2%,respectively.

Pharmacokinetic and statistical analysis of data

Non-compartmental analysis of milbemycin oxime in plasma was performed by using a commercially available software program (WinNonlin 4.0, Pharsight Corporation, CA, USA).The area under the concentration versus time curve to infinite time(AUC0→∞) and the area under the first-moment curve(AUMC0→∞) were calculated by the linear trapezoidal rule to the last quantifiable plasma concentration(Clast) and further extrapolated to time infinity by dividing the last concentration point by the elimination rate constant (λz); the terminal rate half-life(t1/2λz) was calculated by linear least-square regression analysis using the last five log-transformed plasma concentration points; the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and time to reach the maximum plasma concentration (Tmax) were obtained by visual inspection of the experimental data; AUMC0→∞divided by AUC0→∞provided the mean residence time(MRT), and the mean absorption time (MAT) was the difference between MRT obtained after oral (per os,PO) administration and MRT after intravenous (IV)administration.

The bioavailability (F, %) after PO administration was calculated by the formulaF=AUCPO/AUCIV×DoseIV/DosePO×100%.Further pharmacokinetic parameters determined, included the total clearance(Cl=Dose/AUC0→∞), volume of distribution based on the terminal phase (Vz=Dose/λz/AUC0→∞).Cl andVzafter oral administration were initially calculated by WinNonlin directly, as Cl/FandVz/F, respectively.To obtain the real Cl andVz, they were corrected byF.

Pharmacokinetic parameters were reported as mean±standard deviation (mean±SD), their statistical evaluation of parameter was performed by using SPSS 13.0 software.A non-parametric Mann-Whitney test was utilized to compare the mean values of parameters.

Binding of milbemycin oxime in dog plasma

Protein binding of milbemycin oxime was determined by equilibrium dialysis at concentrations spanning the range of values observedin vivoin dog plasma.The perspex dialysis cell unit contained two reservoirs(750 μL volume in each) separated by a Spectra/ Por-2 membrane (Spectrum Laboratories, Inc., Rancho Dominguez, Calif.).Fresh plasma pooled from four drug-free dogs was adjusted to pH 7.4 with 0.5 mol · L-1hydrochloric acid and spiked with milbemycin oxime at 50, 100 and 200 ng · mL-1.Two replicates at each concentration were incubated at 37℃ for 30 min.A portion (600 μL) of the plasma (donor) was dialyzed against the same volume of isotonic phosphate buffer (pH 7.4, 0.067 mol · L-1) (acceptor) at 37℃ for 24 h.Samples of plasma and buffer were removed from each reservoir and stored at –20℃ by analysis.The fraction of drug unbound in plasma (fu) was calculated as the ratio of milbemycin oxime concentration in buffer to that in plasma and was expressed as a percentage.

Results

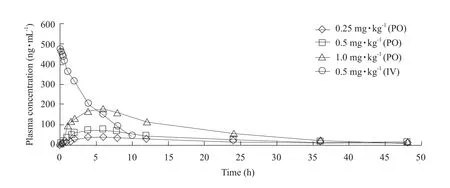

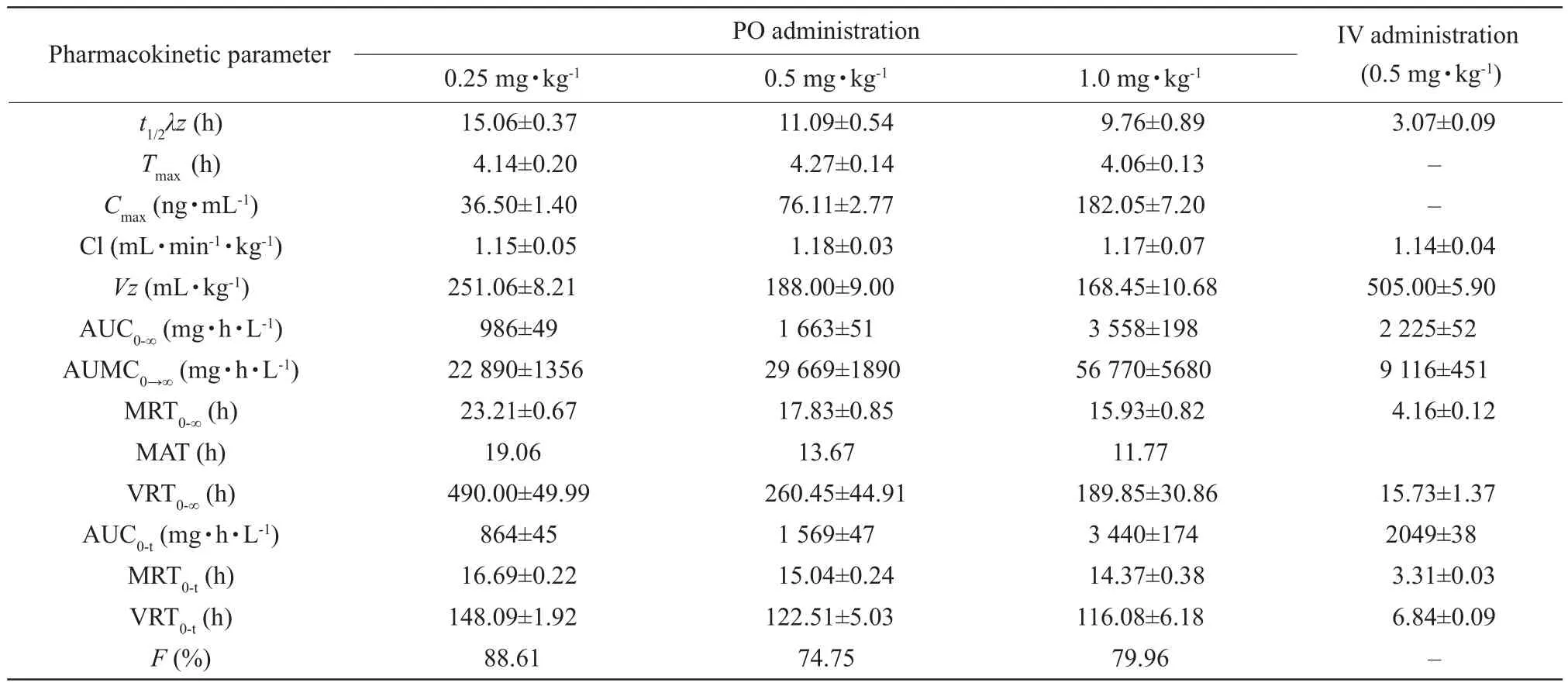

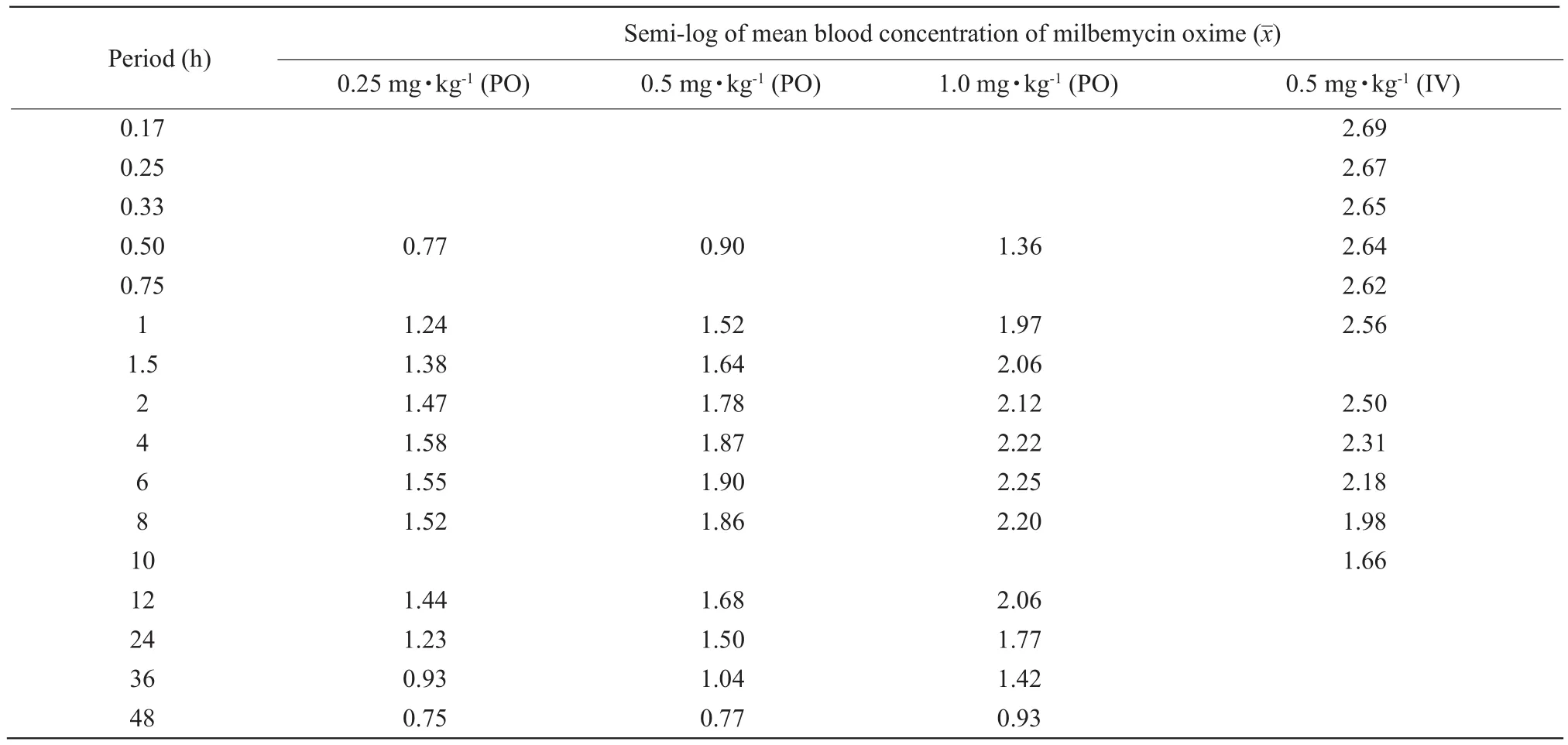

No signs of discomfort were observed in the dogs after PO or IV administration of milbemycin oxime.Fig.1 showed the mean plasma milbemycin oxime concentration-time curves obtained after its oral administration as tablets at three different dose rates(0.25, 0.5 and 1.0 mg · kg-1) and after its intravenous administration at a dose rate of 0.5 mg · kg-1in dogs.Fig.2 showed the semi-log plasma concentration-time curves of milbemycin oxime in dogs.The main pharmacokinetic parameters estimated by non-compartmental analysis and the semi-log plasma concentrations of milbemycin oxime after oral and intravenous administration are presented in Tables 1 and 2.

After PO administration, milbemycin oxime was slowly absorbed and eliminated.The absorbed amount followed a linear dose-relationship, asCmaxand AUC0→∞increased proportionally with the administered dose rates.It was calculated that the absolute bioavailabilities of milbemycin oxime tablet were estimated as 88.61%, 74.75% and 79.96% at dose rates of 0.25,0.5 and 1.0 mg · kg-1, respectively.

Fig.1 Plasma concentrations vs time to dogs following different PO and IV dose rates of milbemycin oxime (mean±SD)PO, Oral administration (per os); IV, Intravenous administration.

Fig.2 Semi-log plasma concentration-time curve of milbemycin oxime in dogs following different PO and IV dose rates PO, Oral administration (per os); IV, Intravenous administration.

Table 1 Pharmacokinetic parameters (mean±SD) of milbemycin oxime after PO and IV administrations in beagle dogs

t1/2λz, Terminal rate half-life;Tmax, Time to reach the maximum plasma concentration;Cmax, Maximum plasma concentration; Cl, The total body clearance;Vz, Apparent volume of distribution; AUC0-∞(t), Area under the concentration versus time curve to in finite (t) time; AUMC0→∞, Area under the first-moment curve; MRT0-∞(t), Mean residence time from zero to in finite (t) time; MAT, Mean absorption time; VRT0-∞(t), Variance of residence time from zero to in finite (t) time;F, Bioavailability; –, Unknown data.

Table 2 Semi-log plasma concentrations of milbemycin oxime after oral and intravenous administration

After IV administration at the dose of 0.5 mg · kg-1,milbemycin oxime presented a volume of distribution(Vz) of 50.50±0.59 mL · kg-1and AUC0-∞of 2 225±52 mg · h · L-1.Cl was 1.14±0.04 mL · min-1· kg-1andt1/2λzwas 3.07±0.09 h.In the protein binding test,values offuwere 0.12%, 0.14% and 0.13% in dog plasma at 50, 100 and 200 ng · mL-1, respectively.

Discussion

Macrocyclic lactone (macrolide) antiparasitic drugs comprise two major groups: milbemycins and avermectins.The former group included milbemycin oxime and moxidectin.The latter one included ivermectin, abamectin, selamectin and eprinomectin.The pharmacokinetic behaviours of ivermectin and doramectin had been investigated more extensively as they were so far the most widely used parasiticides across animal species.However, very few recent pharmacokinetic data of milbemycin oxime in dogs were available.McKellar and Benchaoui (1996)reported that the pharmacokinetic behaviours of avermectins and milbemycins were significantly affected by route of administration, pharmaceutical formulation, and interspecies and interindividual variation, but due to their highly lipophilic nature,these anthelmintics were extensively distributed throughout the body and slowly eliminated with faeces regardless of the administration route in all the species.It was reported that the absorption of ivermectin was faster in dogs than that in ruminants and pigs, and similar to horses (Gokbulutet al., 2006; González Cangaet al., 2009).In horses, although subcutaneous injection resulted in a greater bioavailability than does oral administration (AUCoral=36.5% of AUCsc), the oral route was preferred, as parenteral administration could produce local swelling and other adverse reactions(Anderson, 1984).

In the present work, by LC-MS/MS analysis, the pharmacokinetics of milbemycin oxime in dogs were shown to be linear with the dose-dependent increase in AUC andCmax.The data above are in agreement with report of Ideet al.(1993), in which milbemycin 5-oxime concentrations in dog plasma were determined by method of enzyme immune assay,and also in accordance with the pharmacokinetic properties of ivermectin by oral, intramuscular or subcutaneous routine (González Cangaet al., 2009).The drug plasma level reached a maximum in all the dogs approximately 4 h, showing that milbemycin oxime given orally was slowly absorbed into vascular compartment and persisted in the body for a prolonged period, mainly due not only to the lower Cl, but also to longer elimination half-life as ivermectin(González Cangaet al., 2009).The half-life was found to be longer after oral than after IV doses, probably because the oral elimination could be affected by intestinal environmental impact as enteroheptic cycle,existence of specific absorption site; in addition, small differences in formulation might result in substantial changes absorption (Lifschitzet al., 2004), the accessories in the oral medicine preparation might affect the drug release, then influence its absorption and elimination, resulting in its longer biological half-life.

The binding study in dogs had shown that milbemycin oxime had higher plasma protein binding(about 96% to 98%), which was similar to ivermectin(Rohrer and Evans, 1990).The binding drug could not be metabolized, and stored in blood temporarily.The apparent volume of distribution (Vz), one of the most widely used parameters for drug distribution, was lower (168-251 mL · kg-1) in this work, showing that the milbemycin oxime concentration in plasma was higher than that in tissues, being favourable for killing haematophagous parasites likely leading to highly prophylactic and curative efficacy against canine heartworm.The livers could be regarded as temporary deposit organs of milbemycin oxime, in which the drug clearance depended on the hepatic blood flow and intrinsic clearance which was the main metabolic style under the certain hepatic blood flow.The rate of elimination depended on the livers' inherent ability to metabolise the drug, and the amount of drug presented to the livers for metabolism.This is important because drugs administered orally are delivered from the gut to the portal vein to the livers: the livers gobble up a varying chunk of the administered drug (pre-systemic elimination) and less is available to the body for theraputic effect.In the present study, milbemycin oxime had higher plasma volume and protein binding,resulting in lower rate of elimination.The adipose tissues might be deposit organs, due to its high lipophilic nature, so milbemycin oxime might have a prolonged period in the body.The drug distributed to other organs smoothly through plasma (Ideet al.,1993).Like ivermectin through bile as the main route of excretion, milbemycin oxime was mainly eliminated in the faeces, the faecal excretion accounted for 90%of the dose administered with <2% of the dose excreted in urine (Ideet al., 1993; González Cangaet al., 2009).

Bioavailability is the cornerstone of deciding the drug dose-effect relationship.There is no previous data available describing PO bioavailability of milbemycin oxime in dogs.In our study, at the oral dose of 0.50 mg · kg-1, its absolute bioavailability was estimated to be 74.75%, without significant differences with those of 0.25 and 1.0 mg · kg-1, indicating that the tested tablets containing milbemycin oxime were appropriate in dogs by oral administration at a single dose of 0.50 mg · kg-1.

Conclusions

In summary, it was the first pharmacokinetic study of milbemycin oxime following oral administration in dogs by LC-MS/MS analysis.Consideration of its higher oral bioavailability and advantageous pharmacokinetic properties (e.g.its lower total body clearance and longer elimination half-life) showed that 0.50 mg · kg-1oral administration of milbemycin oxime allowed good distribution and concentration of the drug in blood, supporting the recommended dose application of milbemycin oxime in parasitological efficacy studies.

Anderson R R.1984.The use of ivermectin in horses: research and clinical observations.Compendium on Continuing Education, 6:S517-S520.

Bater A K.1989.Efficacy of oral milbemycin against naturally acquired heartworm infection in dogs.Proceedings of the Heart worm Symposium '89, Charleston, South Carolina.pp.17-19.

Beech R, Levitt N, Cambos M,et al.2010.Association of ion-channel genotype and macrocyclic lactone sensitivity traits inHaemonchus contortus.Molecular & Biochemical Parasitology, 171: 74-80.

Bowman D D, Ulrich M A, Gregory D E,et al.2005.Treatment ofBaylisascaris procyonisinfections in dogs with milbemycin oxime.Veterinary Parasitology, 129: 285-290.

Danaher M, Howells L C, Crooks S R H,et al.2006.Review of methodology for the determination of macrocyclic lactone residues in biological matrices.Journal of Chromatography B, 844: 175-203.

Edwards G.2003.Ivermectin: does P-glycoprotein play a role in neurotoxicity?Filaria Journal, 2(Suppl 1): S8.

Ferroglio E, Rossi L, Tomio E,et al.2008.Therapeutic and prophylactic efficacy of milbemycin oxime (interceptor) againstThelazia callipaedain naturally exposed dogs.Veterinary Parasitology, 154:351-353.

Genchi C, Cody R, Pengo G,et al.2004.Efficacy of a single milbemycin oxime administration in combination with praziquantel against experimentally induced heartworm (Dirofilaria immitis)infection in cats.Veterinary Parasitology, 122: 287-292.

Gokbulut C, Karademir U, Boyacioglu M,et al.2006.Comparative plasma dispositions of ivermectin and doramectin following subcutaneous and oral administration in dogs.Veterinary Parasitology, 135: 347-354.

González Canga A, Sahagún Prieto A M, Diez Liébana M J,et al.2009.The pharmacokinetics and metabolism of ivermectin in domestic animal species.The Veterinary Journal, 179: 25-37.

Guerrero J, McCall J W, Genchi C.2002.In: Vercruysse J, Rew R S.The use of Macrocyclic lactones in the control and prevention of heartworm and other parasites in dogs and cats.Macrocyclic lactones in antiparasitic therapy.CABI Publishing.pp.353-369.

Holm B R.2003.Efficacy of milbemycin oxime in the treatment of canine generalized demodicosis: a retrospective study of 99 dogs(1995-2000).Veterinary Dermatology, 14: 189-195.

Humbert-Droz E, Büscher G, Cavalleri D,et al.2004.Efficacy of milbemycin oxime againstAncylostoma tubaeforme(fourth stage larvae and adults) in artificially infected cats.Veterinary Record,154: 140-143.

Ide J, Okazaki T, Ono A.1993.Milbemycin: discovery and development.Annu Rep.Sankyo Research Laboratory, 45: 1-98.

Kelly P J, Fisher M, Lucas H,et al.2008.Treatment of esophageal spirocercosis with milbemycin oxime.Veterinary Parasitology, 156:358-360.

Kok D J, Williams E J, Schenker R,et al.2010.The use of milbemycin oxime in a prophylactic anthelmintic programme to protect puppies,raised in an endemic area, against infection withSpirocerca lupi.Veterinary Parasitology, 174: 277-284.

Kok D J, Schenker R, Archer N J,et al.2011.The efficacy of milbemycin oxime against pre-adultSpirocerca lupiin experimentally infected dogs.Veterinary Parasitology, 177: 111-118.

Lifschitz A, Sallovitz J, Imperiale F,et al.2004.Pharmacokinetic evaluation of four generic formulations in calves.Veterinary Parasitology, 119: 247-257.

Mckellar Q A, Benchaoui H A.1996.Avermectins and milbemycins.Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 19: 331-351.

Mckellar Q A, Jackson F.2004.Veterinary anthelmintics: old and new.Trends in Parasitology, 20: 456-461.

Okazaki T, Ono M, Aoki A,et al.1983.Milbemycins, a new family of macrolide antibiotics: producing organism and its mutants.Journal of Antibiotics, 36: 438-441.

Rohrer S P, Evans D V.1990.Binding characteristics of ivermectin in plasma from Collie dogs.Veterinary Research Communications, 14:157-165.

Schenker R, Cody R, Strehlau G,et al.2006.Comparative effects of milbemycin oxime-based and febantel-pyrantel embonate-based anthelmintic tablets onToxocara canisegg shedding in naturally infected pups.Veterinary Parasitology, 137: 369-373.

Schenker R, Bowman D, Epe C,et al.2007.Efficacy of a milbemycin oxime-praziquantel combination product against adult and immature stages ofToxocara catiin cats and kittens after induced infection.Veterinary Parasitology, 145: 90-93.

Scott D W, Jr Miller W H, Griffin C E.2001.Small animal dermatology.6th ed.W.B.Saunders, Philadelphia.pp.457-474.

Shoop W L, Helmut S M, Michael H F.1995.Structure and activity of avermectins and milbemycins in animal health.Veterinary Parasitology, 59: 139-156.

Takiguchi Y, Mishima H, Okuda M.1980.Milbemycin, a new family of macrolide antibodies: fermentation, isolation and physico-chemical properties.Journal of Antibiotics, 33: 1120-1127.

Wolstenholme A J, Rogers A T.2005.Glutamate-gated chloride channels and the mode of action of the avermectin/milbemycin anthelmintics.Parasitology, 131: S85-S95.

Wolstenholme A J.2010.Recent progress in understanding the interaction between avermectins and ligand-gated ion channels:putting the pests to sleep.Invert Neuroscience, 10: 5-10.

Journal of Northeast Agricultural University(English Edition)2018年1期

Journal of Northeast Agricultural University(English Edition)2018年1期

- Journal of Northeast Agricultural University(English Edition)的其它文章

- Effect of Inoculation Rhizobium and Response of Soybean-Rhizobium System to Insoluble Phosphate

- Characteristics and Degradation Mechanism of Fomesafen

- Comparative Study of Proximate, Chemical and Physicochemical Properties of Less Explored Tropical Leafy Vegetables

- A Comparative Study on Photosynthetic Characteristics of Dryopteris fragrans and Associated Plants in Wudalianchi City, Heilongjiang Province, China

- Effect of Mineral and Vitamin Supplementation on Performance and Haemotological Values in Broilers

- Comparative Research on Facultative Anaerobic Cellulose Decomposing Bacteria Screened from Soil and Rumen Content and Diet of Dairy Cow