Demolition Dolls

The eviction notice came on the last day of June this year. For the residents living in Baishizhou, Shenzhen’s largest “urban village,” the end had finally come.

In 2017, the southern metropolis announced plans to transform all its urban villages into “clean, orderly, harmonious, safe, and happy homes” by July 2020. At the beginning of the year, there were 83,000 registered residents—possibly up to 150,000, according to some estimates—living in Baishizhou’s “handshake houses”

(握手樓), as neighbors call the multi-story buildings along alleys so narrow one might shake hands across them.

Many are young graduates and migrant workers, making their first way in the city. Having first arrived in Shenzhen in 2007, Hubei-born performance artist Nut Brother was once one of them. Now he’s lending them his voice.

“Parents with school-aged children were panic-stricken,” said Nut Brother, as China’s annual school-transfer applications are normally due in April. The sudden need for housing has seen higher rents in surrounding neighborhoods further inflate. Many began to contemplate packing up their “Shenzhen Dreams” to return home.

Amid the sweep of demolition notices, Nut Brother and his friends Zheng Hongbin, Zhang Xing, Shi Jie, and Duan Peng circulated posters asking Baishizhou families to donate toys for an art project to three collection points: a local vegetable stall, a mahjong hall, and a tattoo parlor.

The team eventually collected 400 toys over two weeks, some carrying the children’s names and the message written in black marker: “Baishizhou is being demolished. I don’t want to lose my education.” Each toy symbolized an affected child, as the Chinese word for “doll” (娃娃) is also a term of endearment for children.

Then, on August 4, a 29-ton hydraulic excavator—“a symbol for urban renewal,” explained Nut Brother—hummed to life on a plot of land between the Shenzhen and Huizhou border. A giant claw swirled over each toy lined up on the ground by volunteers, and clamped down. For five hours, each toy was lifted meters into the air before being deposited into a wetland on the other side of a fence.

“The message is clear and direct,” Nut Brother told TWOC. “The developer doesn’t care at all about tenant rights, causing several thousand children to have trouble re-enrolling in schools. Maybe the developer can say, ‘I don’t care about the people,’ but the government can’t say this.”

Having garnered attention in a handful of domestic media outlets for the performance, Nut Brother had hoped to find an exhibition site in Beijing, but unfortunately, “Nobody dared to give us space.” Instead, the artist turned to WeChat, enlisting 1,300 supporters who pledged to lend their social media feed as an online exhibition space, sharing project posters about the situation of Baishizhou families. “If we can’t get more media, we can all become media.”

Baishizhou’s days may be numbered, but Nut Brother is still intent on giving its tenants a voice. “It seems that those with money and property have the right to speak, and those without money can be forced [out],” he said. “The government should listen equally to all voices that have a stake in what happens to the land.”

– Tina Xu (徐盈盈)

Visible Darkness

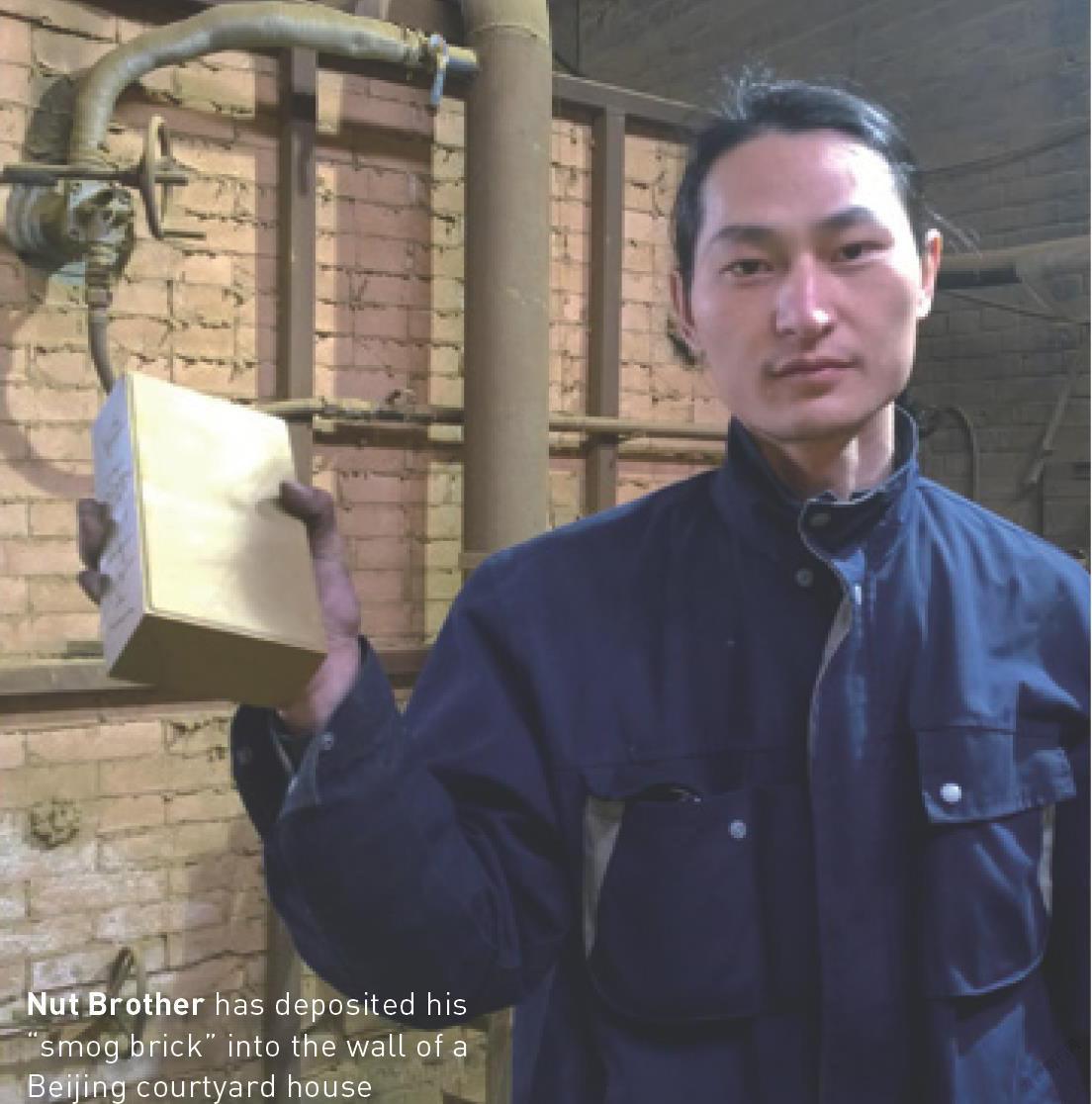

Hubei-born artist Wang Renzheng, better known as “Nut Brother,” rose to international fame in 2015 after he walked the streets of Beijing with an industrial vacuum cleaner for 100 days and transformed the accumulated PM 2.5 particles into a physical brick—turning, in his words, “an invisible problem into a clearly visible object.” A mastermind of jarringly symbolic performances, he has grappled with issues from environmental protection to education for migrant workers’ children.

“It’s nerve-wracking,” Nut Brother says with a soft laugh. When he spoke with TWOC, he had recently been released from 10 days’ detention, and was still dodging invitations from public security officers to “have tea.” Nevertheless, the subversive artist shares what it is like to work within “the cracks of this larger ecosystem” to “reveal the hidden side of things.”

How did you begin as an artist?

Between graduating from university in 2004, and starting to do art in 2011, I was in advertising for many years. It was pretty painful. The goal of advertising is to encourage spending. Often, you take people’s weaknesses and enlarge them, and endlessly expand people’s desires. I find that art is a reverse process that can criticize these very things.

Can you talk about your piece last year on water pollution?

Residents of Xiaohaotu village have complained of polluted drinking-water for many years. While the Shaanxi Environmental Protection Bureau admitted that the levels of heavy metals exceeded the standard, they wouldn’t admit that it was related to the natural gas and coal operations in the area.

So I went there with friends and investigated for around 10 days. We exchanged 10,000 Nongfu Spring water bottles with the villagers for their polluted drinking water. We brought the bottles filled with dirty water to exhibit in Beijing and Xi’an, creating a “supermarket” in the 798 Art District. It became a trending topic on Weibo. After around 10 days in Beijing, we were shut down for copyright infringement, so we got a van and continued to exhibit. The police came to us again and told us that we had parked illegally.

What has been the result of your piece?

On the second day of our exhibit in Beijing, the local government [in Shaanxi] put together an investigation committee. They found no problems. The residents didn’t believe it. Nobody believed it. The government wanted to release their water quality report and hold a press conference. We said, “If you hold a press conference, we’ll hold our own press conference in Beijing.” They cancelled their press conference. They never released the report to the public. To this day, I haven’t seen this so-called report.

The water in Xiaohaotu hasn’t improved on the whole, but there are some steps forward. The government put forward money to make a deepwater well. The China National Coal Group strengthened the leaking base of their wastewater reservoir, and spent some money to treat the water. But Sinopec gave no response. They directly pour their wastewater deep underground. There’s still not a single person to stand up and say how we are going to clean it up.

Would you consider the piece a success?

We can’t say. There are small improvements, but to do this kind of work, failure is a foregone conclusion. What is success? For governments and businesses to admit that they do have a responsibility.

How is art related to society?

Art can’t be separated from society. Art should be on the scene of action, and connected to the people living on this Earth right now. Some art within the system is a vain production; it has no relation, no resonance—like the scenery atop the surface of a bubble. Sometimes I will do this kind of art, too. But I hope to work within society to observe, find and address problems, and call out to others. There are so many problems I know, they know, we all know, but we all pretend. We know that it may only be a gesture, but it’s important to push the issue forward. Even if the room for discourse that exists is like the sound of a rustling skirt. – T.x.

汉语世界(The World of Chinese)2019年6期

汉语世界(The World of Chinese)2019年6期

- 汉语世界(The World of Chinese)的其它文章

- MY Country,My Cinema

- Sweet Nothings

- 摇

- You’ve got questions? she’s got answers

- 光影

- Rescue Fees