Bile leakage after loop closure vs clip closure of the cystic duct during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A retrospective analysis of a prospective cohort

Sandra C Donkervoort, Lea M Dijksman, Aafke H van Dijk, Emile A Clous, Marja A Boermeester,Bert van Ramshorst, Djamila Boerma

Abstract

Key words: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy; Cystic duct occlusion; Bile leak; Endo-loop

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) is one of the most frequently performed surgical procedures. Bile duct injury is a postoperative complication associated with significant morbidity[1,2]. Reports on the rate of bile duct injury as a complication of LC have consistently varied from 0.5% to 1%[3,4]. Recently, it has been reported that cystic stump leakage rates (type A bile duct injury) are underestimated, especially in a subpopulation of patients with complex biliary disease[5]. Patients with previous biliary events [history of cholecystitis, cholangitis, pre-operative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for suspected choledocholithiasis] or acute cholecystitis are at increased risk (4%-7%) for cystic stump leakage[6,7]. These patients often require percutaneous drainage of the biloma, endoscopic sphincterotomy, stent placement, or even re-laparoscopy or re-laparotomy[5,8].

Bile leakage from the cystic stump can be regarded a preventable complication, if during LC the cystic duct is correctly and securely occluded. To date, the application of non-absorbable metal clips for cystic duct closure is the standard of care in most hospitals and countries[8]. As an alternative for metal clips, we introduced the use of absorbable polydioxanone ligature (loops) for which few reports in literature can be found[1,9-15].

This technique is now the standard for appendix stump closure in appendectomy and has been widely reported. A decrease in bile leakage rate after LC may well be achieved using loop cystic duct closure, especially in the subpopulation of patients with complicated biliary disease. If so, this technique will lead to important improvements in patient safety for patients undergoing LC. However, there is little high quality evidence to support the hypothesis that looping the cystic duct during LC is safer than clipping.

In the present study, we analysed the effect of closure of the cystic duct using polydioxanone loops on overall bile leakage rate from the cystic duct in patients undergoing LC. Leakage rates were additionally assessed for patients identified as being at risk for postoperative bile leakage complication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source

The study cohort was part of a database created for all consecutive patients who underwent LC for symptomatic cholecystolithiasis over a 10-year period (2002-2012)in two large teaching hospitals. Details on data retrieval of both cohorts until 2009 have been previously described in more detail[16,17]. Data entry of patients with loop cystic duct closure into this database ran thereafter until June 2012.

Study population

The looped cystic duct closure was introduced after our previous studies on timing of LC after ERCP showed cystic stump leakage rates to be 3%-5% for patient who had undergone ERCP prior to LC[17,18].

The technique used to close the cystic duct has been recorded in all patients from the original operative reports. The standard of care in that period was the use of three parallel clips, two proximal and one distal, with transection of the cystic duct leaving two parallel clips in situ. In the loop closure group patients underwent an LC in which the cystic stump was closed after transection by a polydioxanone ligature(loop). In September 2010 loop-closure of the cystic stump was introduced in patients who underwent LC for complicated gallstone disease or when confronted with a wide or inflamed cystic duct during LC. After more experience was gained in the use of loops, the use of loop closure in patients with less evidently inflamed cystic ducts became more naturally, and use expanded. When polydioxanone ligature (loop) was used, the cystic duct was transected between two non-resorbable clips. The loop was then placed over de cystic duct stump behind the clip that initially secured the cystic stump.

Patient characteristics and outcome variables

Patient age, gender, co-morbidity as well as disease characteristics were noted. The primary end point of this study was the occurrence of bile leakage from the cystic duct stump. Post-operative bile leakage complications were identified by chart review. Identification of bile leakage complications was done by meticulous screening of postoperative charts, blood results, radiology reports, and readmission notes. To search for all bile leakage complications (predominantly type A bile leaks), the occurrence of post-operative re-interventions by ERCP, percutaneous drainage procedures or re-laparoscopy, and re-laparotomy were checked. In addition,complication data were compared with hospital complication registration systems.

The effect of a loop on bile leakage complication was analysed by determining overall bile leakage rates for both clipped and looped patients. We also assessed the bile leakage rate in the period before the introduction of loop closure in clinical practice (clip closure only period, 2002-2010) in comparison with the period after the introduction of loop closure (mixed closure period, 2010-2012).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 19.0. Statistical significance is expressed asP< 0.05. Categorical data were shown as number (%) and compared using the Pearsonχ2or Fisher’s Exact test (where appropriate). Continuous data were shown as median with interquartile range (25%-75%) and compared using the Mann-WhitneyUtest. In this study we did not use comparative statistics analysis, when describing groups with one or more zero-cell counts as calculation ofPvalue is less reliable in such cases and regular statistical tests are not designed for data with zero events.

From our database, independent risk variables predicting for a bile leakage complication were extracted. Risk variables included patient characteristics such as gender, age, American Society of Anaesthesiology (ASA) classification and body mass index. Furthermore, disease events such as previous choledocholithiasis, acute cholecystitis, pancreatitis and previous cholecystitis operated on in delayed setting were taken into account. With these variables a risk score was created as a tool to identify and define patients at increased risk for a bile leakage complication.Therefore, we used univariate and multivariate analyses with binomial logistic regression. All factors with a univariatePvalue < 0.1 were used in multivariate analysis. A risk score was created using the beta-coefficient from factors contributing to the multivariate analysis, for which variables withP< 0.1 were taken into account because of the small sample size of the loop closure group. Scores were calculated by dividing the beta of each variable by the lowest beta and then rounded. The sum of these values was expressed in a final risk score. For this retrospective study, the Medical Ethical Committee at the OLVG reviewed the study protocol and a waiver was granted.

RESULTS

A total of 4359 patients underwent LC in one of the two hospitals. The median age was 50 years (interquartile range 39-62). About half of the patients were female (54%).A total of 136 of 4359 (3%) patients underwent cystic duct closure by a loop (loop closure group) instead of traditional closure by clips only (clip closure group).

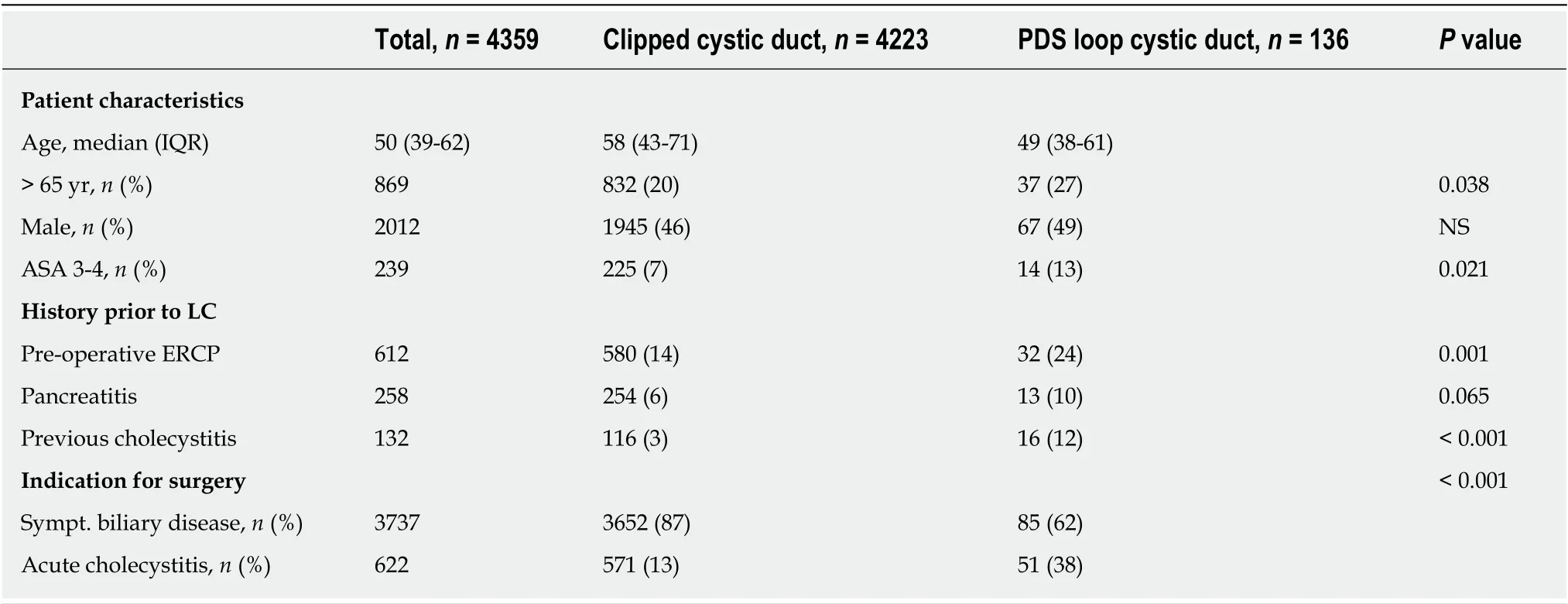

Table 1 shows the demographic data of patients in the clip closure and loop closure groups. Loop closure was significantly more often used in older patients (P= 0.038),co-morbid patients (P= 0.021), and patients with complicated biliary disease: Preoperative ERCP (P= 0.001), previous cholecystitis (P< 0.001) and acute cholecystitis(P< 0.001).

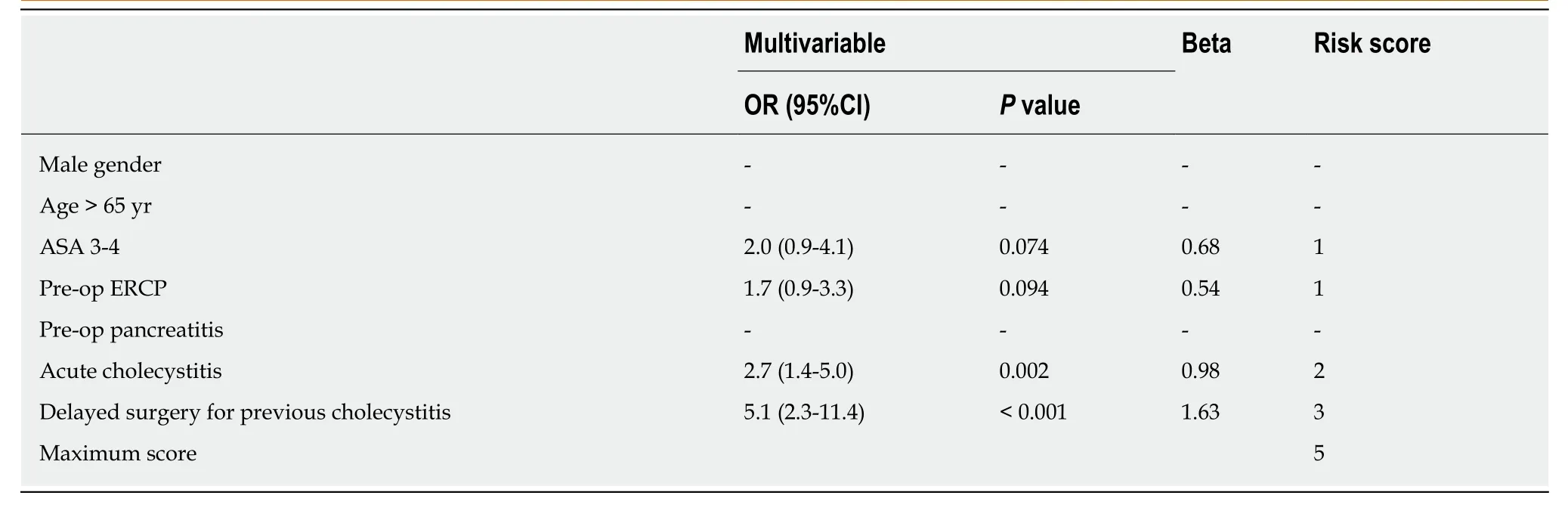

The overall bile leakage rate was 1.4% (59 of 4359 patients). Stratification for bile leakage risk of patients was done by developing a risk score based on logistic regression analysis (Table 2). Patients at risk for bile leakage in our population were patients with a higher (3 or 4) ASA classification (odds ratio [OR]: 1.7, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.9-3.3,P= 0.09), pre-operative ERCP (OR: 1.9, 95%CI: 1.5-2.5,P= 0.037),acute cholecystitis (OR: 2.7, 95%CI: 1.4-5.0,P= 0.002) and/or previous cholecystitis(OR: 5.1, 95%CI: 2.3-11.4,P< 0.001). The risk score, which was deducted from the beta values, showed patients with a previous cholecystitis to be at highest risk for a postcholecystectomy bile leakage complication. Male gender, age, and pre-operative pancreatitis were not independent predictors for bile leakage complication.

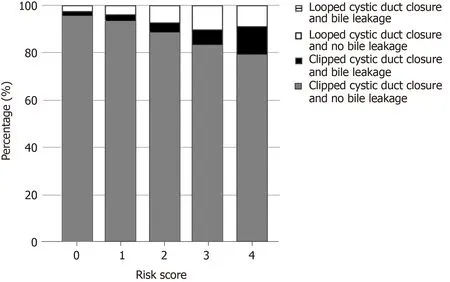

Figure 1 displays the bile leakage rates for both groups as a function of predicted bile leakage risks. The clip closure patients without a predicted bile leakage risk were shown to have a 0.9% bile leakage rate (27 of 3154)vs0% (0 of 60) for the low risk loop closure patients. For patients in the clip closure group with a bile risk score ≥ 1,leakage rate was 3.1% (33/1069), whereas 0% (0/76) in the intermediate-high risk loop closure patients had bile leakage. Leakage rates increased up to 13% (4/30) for patients with a risk score ≥ 4 or higher in the clip closure groupvs0% (0/3) for the loop closure group. No comparative statistics analysis was done because the loop closure group had zero events.

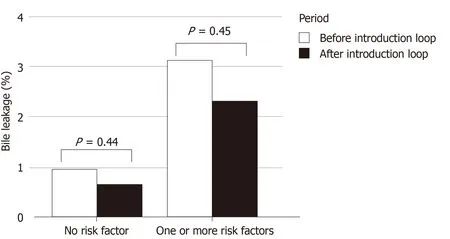

When comparing the time period with clip closure only to the time period in which clip closure as well as loop closure were used, overall bile leakage rates were 1.6%(41/2633) and 1.1% (19/1726;P= 0.2) respectively. No significant differences between observed bile leakage were found between the two time periods when stratifying for predicted risk of bile leakage; 0.9% (9/1307)vs0.7% (18/1907;P= 0.44), respectively for the low risk patients, and 3.2% (23/726)vs2.4% (10/419;P= 0.45), respectively for the high-risk patients (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

In this prospective consecutive series, no bile leakage complications occurred in patients with loop closure of the cystic duct during LC, whereas after clip closure bile leakage rates varied from 2% to 13% depending on patients’ bile leakage risk profile.This result stands out in particular, because loop closure was used more frequently in patients with an increased bile leakage risk.

Recently we showed that bile leakage risk is underestimated in the literature[6].Postoperative bile leakage can occur from cystic duct stump leakage due to unsecured closure of the cystic duct, leakage from an accessory duct on the liver bed (Luska) and injury to the common bile duct. The focus in our study was cystic duct stump leakage(type A bile leaks) due to unsecured closure. If a secure technique can be identified improvements can be pursued, avoiding a potentially life threatening complication.

Leakage rates are consistently reported to be 1%-2%[3,4,19,20]. Patients with uncomplicated symptomatic biliary disease have a 1% bile leakage rate, but a subgroup of patients with complicated biliary disease due to pre-operative ERCP for suspected choledocholithiasis, patients with an acute cholecystitis, and patients with a delayed cholecystectomy have a cystic duct leakage rate up to 6%[6]. The risk score provided the possibility to stratify for pre-operative risk for bile leakage and thus more complex procedures. Present data showed that the loop closure group had a very low leakage rate, even in the more difficult cases.

Focus on bile leakage complications after LC is important as there is a lot to gain. It is an unwanted complication with potential high morbidity inducing high healthcare costs as patients often require endoscopic intervention depending upon the nature of the leakage, with or without a percutaneous drainage procedure, re-laparoscopy, or even re-laparotomy[21-24]. Although the reported success rate of an initial treatment of bile leakage is high (96%), it is still a potentially life threatening situation, possibly leading to sepsis and multiple organ failure due to biliary peritonitis[2].

Table 1 Demographics and baseline data

Bile leakage after LC due to the failure of a closed cystic stump (1%) is preventable if a secure closing technique is used during cholecystectomy[3,25]. Different techniques for cystic duct closure exist, of which the placement of non-resorbable metal clips has been the standard of care to date. Clipped closure is reportedly complicated by postoperative bile leakage due to laceration of the duct[26], through the conduction of electricity[27], necrosis of the clamped tissue[28], or migration of the clips[6,11,29,30],especially when placed on inflamed tissue.

Other techniques of cystic duct closure, such as absorbable clips, ligatures, and vessel sealants, have been proposed. Gurusamyet al[31]reported a systematic review of three trials including a total of 255 patients. Duct occlusion with absorbable clips, nonabsorbable clips, and absorbable ligatures were compared. All three trials consisted of no more than 75 patients per group and were at high risk for bias. No difference in bile leakage complication between the groups was found.

Since the widespread use of harmonic scalpel (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati,OH, United States) and vessel sealants (LigaSure™) in laparoscopic surgery, these techniques have also been explored for closure of the cystic duct. Although studies have shown that these techniques are deemed safe and efficient, they have at least comparable bile leakage rates (1.75%) as clips[32,33].

Reports on other techniques of cystic stump closure (i.e. metal clips, locking clips,ligatures) are limited. There is not enough high quality evidence to either encourage or discourage a specific technique of closure during LC. As the overall bile leakage rate (1%) is low in LC, studies with a large number of patients are necessary to deliver evidence for superior cystic duct closure. When searching for a superior cystic duct closure technique, a study design with a subpopulation of high-risk patients will give the best insight. None of the aforementioned studies used a subpopulation with an increased risk for bile leakage complication for analysis. We are the first to analyse bile leakage complication in a subpopulation of patients with multiple risk factors for leakage. Previously we found that LC is technically more difficult in “complicated”biliary disease compared to patients with “uncomplicated” biliary disease[7,14]. Here,we show that bile leakage outcome is different for these subgroups and advocate to recognise that patients with gallstone disease consist of two different disease entities,”uncomplicated” and “complicated” disease.

Present data should be regarded with caution. A few limitations of the present study have to be highlighted: First, the low number of looped patients; the looped cohort consisted of only 3% of the total population. No events/bile leakage occurred in the looped cystic duct group, which made statistical analysis difficult. The lack of events may have been caused by chance rather than an effect of the loop closure. No formal sample size calculation was done in this retrospective setup. Larger patient populations are needed to be able for a more accurate estimation of the effect.However, with all limitations in mind, loop closure of the cystic duct performed far better than the clip closure group, and foremost, better than expected based on predicted risk of postoperative bile leakage.

Table 2 Stratification of 4359 patients after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, according to risk score prediction of bile leakage based on a logistic regression model

Figure 1 Identified risk for a bile leakage complication and bile leakage rate for clip closure and loop closure patients. X-axis: Summarised risk score for bile leakage complication; Y-axis: Percentage of patients with and without bile leakage in loop closure patients and cystic duct closure patients.

Figure 2 Bile leakage complication rate in patients after laparoscopic cholecystectomy for the period with only clip closure of the cystic duct (clip closure only period) and the period after loop cystic duct closure had been introduced (mixed closure period). No risk score: No bile leakage risk according to risk score prediction of Table 2; Risk score ≥ 1: Bile leakage risk score ≥ 1 according to risk score prediction of Table 2.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Joep. E.E.M Maeijer from the AVD of Teaching Hospital at OLVG for his creative support in creating figures.

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery2020年1期

World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery2020年1期

- World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery的其它文章

- Isolated colonic neurofibroma in the setting of Lynch syndrome: A case report and review of literature

- Outcomes associated with the intention of loco-regional therapy prior to living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma

- Pathological abnormalities in splenic vasculature in non-cirrhotic portal hypertension: Its relevance in the management of portal hypertension