Purpose-driven Texts and Paratexts:A Comparative Study of Three Retranslations of Xixiang ji

Ann-Marie HSIUNG

I-Shou University

Abstract Ranked among the top three classics of world drama (Xu,2008,p.26),Xixiang ji 西厢记 is translated more than any other plays from China for its canonic status.This article examines three significant English translations in recent decades.From the U.S.,there is The Story of the Western Wing (1995) by prominent Western sinologists Stephen H.West and Wilt L.Idema.From China,there is the Romance of the Western Bower (2000/2008) by leading literary translator Xu Yuanchong.Finally,from Singapore,and arguably the first intersemiotic translation for stage performance,there is The West Wing:A Renaissance Production with Modern Music and Dance (2008a)by Grant Shen.On the basis of previous translations,these retranslators promote the particular values of the drama that they cherish,as evident in their texts,paratexts,and ST choice.West-Idema’s emphasis on scholarly semantic correspondence disregards the original need for stage performance.Xu’s effort in trumpeting the elegance of Chinese classics divorces his rendition from the colloquial and vigorous zaju tradition of ST.Last but not least,Shen’s imitation of ST musicality and his catering for audience taste result in distortions to stage script.This study,by critically comparing and contrasting these three retranslations via the interrelation between their texts and functional paratexts,hopes to help reveal the drama’s richness and nuances that have been missed or suppressed by any one rendition.

Keywords:Xixiang ji,retranslations,texts and paratexts,Chinese drama

1.Introduction

Considered by many as the best Chinese play (Xu,2008,p.17; Jiang,2009,pp.7-8),Xixiang ji西厢记enjoys unmatched popularity among dramatic literature and performing arts.Though drama as a genre has often been belittled in traditional China,the canonic status ofXixiang jiwas recognized as early as in the 15th century by liberal-minded literati.Jia Zhongming (ca.1343-1423),a prominent theater historian,praised it as “winning the highest place under the sun” among all the musical theaters,be them new or old (as cited in Zhong,1959,p.173).Wang Jide,a noted playwright and theater theorist,viewed its author Wang Shifu as “unprecedented in playwriting and unrepeatable in talent” (1995,p.ii).Its domestic reputation has no doubt contributed to its numerous translations,more than other traditional Chinese plays,introducing this medieval Chinese masterpiece to global audiences.

This study compares three distinctive and functionally diverse English retranslations in recent decades with intent to reveal how this masterpiece is reinterpreted and represented in modern English world.Retranslations,according to Lawrence Venuti (2013),create values by taking into consideration receptor factors and by justifying their difference from one or more existing versions; their source texts are usually those already achieving canonical status.Wang Shifu’sXixiang jimatches Venuti’s criteria and is considered as “one of those masterworks of world literature that merits a new translation with every generation” (West & Idema,1995,p.14).The retranslators discussed in this study are all purpose-driven to make a difference—to improve upon previous versions in one way or another.Their value makings are pronounced in the paratexts of introduction,preface,graphic design,color code,imagery,etc.,and realized (more or less) in the text of retranslations.

The three English retranslations examined and compared areThe Story of the Western Wing(1995)by Stephen H.West and Wilt L.Idema from the U.S.,Romance of the Western Bower(2000/2008) by Xu Yuanchong from China,andThe West Wing:A Renaissance Production with Modern Music and Dance(2008a) by Grant Shen from Singapore.Among them,Shen’s work claimed to be the first stage script serving the purpose of live operatic performance (Shen,2012b,p.183) and may be viewed as intersemiotic translation.This article will conduct a comparative study on text and paratext of these translations,paying special attention to the retranslators,their choices of source text,and how the retranslations react to previous translations.

2.Retranslators,source texts,and English texts

Xixiang ji,is probably China’s most popular love story,comparable to Shakespeare’sRomeo and Juliet(Xu,2008,p.32).Since its original composition by Wang Shifu (ca.1250-1300) during the Yuan Dynasty(1271-1368),this play has engendered numerous reproductions,imitations,parodies and adaptations,both for close reading and theatrical performance.The story of a love affair between a gentry lady and a scholar without parental approval pointedly challenged the prescribed social norm in pre-modern China,with its highly charged romantic scenes often deemed offensive by conventional moral judgment.Xixiang jiexperienced repeated official bans,which nonetheless failed to stop its circulation or performance.Viewed as lovers’ bible and potentially lethal (Rolston,1996,p.231),it has influenced the so-called “talent and beauty” romance tradition in Chinese drama and fiction.Its far-reaching influence is further evident in the well-known classic Chinese novels such as the Ming dynastyJin Ping Mei(The Golden Lotus) (ca.1618) and the Qing DynastyHonglou meng(The Dream of the Red Chamber) (1791) (West & Idema,1995,p.3; Jiang,2009,pp.433-459).

To translate such a traditional Chinese drama replete with arias and allusions,the expertise of the translators is essential.The retranslators discussed here,in particular,are distinctive scholars erudite in classic Chinese language and literature.West and Idema are reputed sinologists and professors of Chinese literature at the University of California,Berkeley and Netherlands’s Leiden University when they teamworked on this translation.Xu Yuanchong is China’s renowned literary translator and professor of English/French literature at Beijing University.Grant Shen is an Asian theater specialist born in China and an associate professor at National University of Singapore during the translation and production ofThe West Wing.They were all teaching at top universities of the countries they were based in.Among them,West and Idema are Westerners with PhD in Chinese,while Xu and Shen are of Chinese origin,one studying two years in France on comparative literature and Western literature and the other obtaining PhD in theater in the U.S.Despite not having an official doctorate degree,Xu is most advanced in age and the most productive translator,whose expertise could be largely derived from his aptitude and life-long dedication to translation.Their professional identity and academic training no doubt have affected their choice of ST,translation approach,and how they assert themselves in their texts.

As the popularity ofXixiang jihas resulted in numerous editions,the highest among vernacular Chinese literature (West & Idema,1995,p.7),there are plenty of choices of ST for the translators.West and Idema establish their difference by choosing the Hongzhi 弘治 edition of 1498,the earliest and most reliable extant version,as their ST.The Hongzhi edition was discovered and made known to the scholarly world only in the late 1940s (West & Idema,1995,p.7; Jiang,2009,p.419).West and Idema’s rigorous scholarly training of sinology could have prompted them to prioritize the authenticity of ST; they are the first to launch into the oldest edition for their English text.Xu Yuanchong,however,preferred to take the most popular Qing dynasty edition (1656) as his ST—the one edited and commented by talented literary critic Jin Shengtan (1610-1661).The idiosyncratic critic Jin asserted himself in Wang’sXixiang jiwith his heavy editorial hands,leading to substantial textual changes,mostly in prose dialogue,supposedly to refine its vulgar language.Jin made the utmost efforts to defyXixiang ji’s notorious name as a “licentious book” by defending for the young lovers and toning down its naturalistic features (Zhang,2005,p.3).His witty and insightful commentary improved reader-friendliness,hence increasing the general acceptability of the play (West & Idema,1995,p.9).Jin’s edition has become the most widely circulated,and is the most popular blueprint for Western translations.While making no difference in ST choice from earlier versions,Xu attempts to improve the literary quality of the existing English texts in terms of form,meaning,and expression.

Shen’s choice of ST differs from the others.Rather than the academic,acclaimed Hongzhi or the popular Jin edition,he adopted Li Rihua’s Mingchuanqiedition as ST for the sake of performance.Since the performance information and music of Yuanzajudrama gradually died out during the Ming Dynasty(1368-1644),playwright Cui Shipei and Li Rihua (1565-1635) adapted Wang’s originalzajulibretto into the then mainstreamchuanqimusic,and thus promoted and prolonged the play’s stage life,especially afterzajuceased to be performed in opera houses.As Li was the one that made the final revision,their work came to be known as Li’schuanqiedition.It is a full-fledgedchuanqiadaptation; apart from reworking of libretto and restructuring the acts to allow multiple singing roles,there were minor alterations in prose dialogue to link contemporary expression and to further entertainment value on stage.Shen (2013,p.179)argues for the necessity of using Li’s MingChuanqiedition for his ST in his research paper:

China’s classical drama peaked during Yuan Dynasty,when simplicity and immaturity marked its performance.[…] The Ming Chinese bridged the gap between the best dramatic literature of the preceding Yuan and the most effective performance practice of their contemporary stage by makingchuanqiadaptations ofzajuplays.

Shen highly praiseschuanqiadaptations ofzajuplays in Ming China as the “golden age of Chinese opera performance” (2013,p.179),comparable to the period of Elizabethan theater in Renaissance England.Shen sufficiently justifies his choice of Li edition as his ST; however,he prefers to have his libretto translation based on Wang’s original from the Hongzhi edition,considering it as unmatched.

As for the prior English texts ofXixiang jitranslation,they were by and large based on Jin edition.The best known among earlier translations was the first complete English rendition,Shi-I Hsiung’sThe Romance of the Western Chamber,published in London during the 1930s.Hsiung views his version as faithful,but acknowledged the extreme difficulty of translating libretto,opting to unrhymed verse in order to focus on semantic accuracy.Hsiung (1936,p.x1) finds his translation a humbling experience:

I hope the good qualities of this book will remain shining in spite of my clumsy English.However,gentle readers,when you find the poetry beautiful,let the merit be attributed to the original authors; and when you find phrases and words unworthy of the name of literature,the translator alone is to blame.

Hsiung’s modesty is not so readily seen in later translators,and his version soon became the standard translation,being reissued in 1968 by Columbia University Press with C.T.Hsia’s commentary as introduction.While praising the readability and reliability of the Hsiung version,Hsia lamented that Hsiung based his translation on the tempered Jin edition and thus missed out some succinct features of the original text (Hsia,1968).Hsiung’s gentle and reserved style of translation could also have to do with the lingering effect of conservatism from Victorian era during the time when his version was first published in the U.K.

Another version about the same period was Henry H.Hart’sThe West Chamber,A Medieval Drama,published by Stanford University Press in 1936.Despite being published by a noted U.S.publisher,Hart’s version did not receive as much attention.It was even critiqued as skipping period slang and misreading the libretto,thus leading to an “incomplete text and some unintelligible scenes” (Shen,2013,p.181).Presenting the libretto as free verse,Hart rebukes the rhymed German version of 1926 in his preface as distorting the sense of the original (West & Idema,1995,p.14).

There were two less known versions in the 1970s before the West-Idema version appeared in the 1990s.One is Henry W.Wells’s English rendition of 1972 asThe Western Chamber,collected inFour Classical Asian Plays,while another by T.C.Lai and S.E.Gamarekian published in 1973,under the same title as Hsiung version.Ironically,Wells version was but an adaptation of Hart version recasting Hart’s prose passages into blank verse,and unrhymed libretto into rhymed verse.Comparatively,Lai and Gamarekian adopted prose as medium for the whole translation adapting the masterpiece freely.These two versions seem to either go too far from the original or too restrained by the rhyme to the point of distortion.

It takes about four decades from the first two English versions ofXixiang jito the next two.From the two versions of 1970s to West-Idema’s in 1990s (1995),though only two decades apart,present a great leap and a breakthrough.The other two following versions,Xu’s (2000/2008) and Shen’s (2008a) to be discussed,however,are less than one decade apart from one another,indicating the increasing attention to this masterpiece in recent decades.The following tackles the three English texts’ paratextual aspect of retranslators’ intention shown in their introductory message.

3.Paratextual Comparison-I:the retranslators’ intention

Apart from the choice of source text,the retranslators show their differences and claim their values unambiguously in their introductory message,an important component of the paratexts.Brought about by Gerard Genette,paratexts include preface,introduction,title,book covers,illustrations,and other secondary signals relevant to the text (Genette,1997,p.3).Paratext,according to Genette,also means messages that “ensure the text’s presence in the world” (Genette,1987,p.1).Kathryn Bachelor (2018,pp.12-13) highlights Genette’s points about paratext as follows:

The paratext consists of any element which conveys comment on the text,or presents the text to readers,or influences how the text is received […] Any material physically attached to the text by definition conveys comment on the text […] Or influences how a text is received.

The most essential of the paratext’s properties […] is functionality […] the main issue for the paratext is not to“look nice” around the text but rather to ensure for the text a destiny consistent with the author’s purpose.

The author’s purpose or “authorial intention” (Batchelor,2018,p.12) would be referred to as retranslator’s intention here,as Genette has also implied the translated version as a text itself (Batchelor,2018,p.20).Retranslator’s intention is highly emphasized in the retranslation,as argued by Venuti (2013,p.100):

Retranslations typically highlight the translator’s intentionality because they are designed to make an appreciable difference.The retranslator’s intention is to interpret the source text according to a different set of values so as to bring about a new and different reception for that text in the translating culture.

The retranslators ofXixiang jihere do have their intention of interpretation based on different sets of values and criteria,as presented in the introductory message of their texts.

In their extensive 100-page introduction,West and Idema proclaim the value of their ST,assert their purpose,and detail their approach.They proudly declare their ST to be the earliest complete edition,indicating their ambition to present the fullness of this masterpiece to the Western world,“Our aim […]is to provide the Western reader with a rendition that is as close to the original as a literary translation will allow,warts and all” (West & Idema,1995,p.15).It is obvious that they treatXixiang jias literature,and not necessarily drama.They further stress,“Our feeling is that a translation,like an original work of literature,should allow the reader to discover the text for himself” (ibid.,p.52).Abiding by the age-old translation notion of faithfulness,they value the original Chinese play and wish to present it to the Western world as truthful as they can.Acknowledging that their version may appear excessively literal to some,West and Idema explain,“We have been guided by the belief that it is both unnecessary and undesirable to resort to well-worn English equivalents or clichés to smooth over any passages that challenge the reader to active engagement” (ibid.,p.15).Rather than the dominant Anglo-American domesticating translation strategy,their translated texts demonstrate a translatorial orientation to foreignizing approach,which features “sending the reader abroad” (Venuti,1995,p.20) by preserving unique cultural expression of the source text.The source-oriented effort of maintaining foreign characteristics often comes with non-fluent translation style,which may impose a barrier to average readers.

West and Idema’s statement of intention inscribes their visible identity as sinologists and serious scholars of Chinese classics.In addition to the more reliable ST formally unavailable,they distinguish themselves from all previous versions with their paratexts of the longest academic introduction and abundant annotations.As such,they not only question the accuracy of earlier translations,but also make efforts to assist further comprehension for avid readers.Their introduction ranges from background information to literary analysis,including a wealth of intricate language,multiple-layered puns,and complex allusion,which they view as all the more “making for a profound and brilliant literary work” (West& Idema,1995,p.52).By so doing,they hope to “point the way beneath the superficial aspects of the text to deeper levels of signification” (ibid.).From such paratexts,West and Idema signify their reverence towardXixiang jias high literature and rare treasure and point to the fact that no studious scholarly translation of this masterpiece has been done before.

While West-Idema’s text of 1995 is revised upon their 1991 edition entitledThe Moon and the Zither,Xu’s 2000/2008 version is revised upon his 1997 edition,a complete translation extended from his shortened 1992 version.Xu’s retranslation ofXixiang jicomes with numerous editions,all published in China under the same English title—Romance of Western Bower.The one this study shall focus on comes from a state-sponsored project,“Library of Chinese Classics” (大中华文库),published in 2000 and reprinted in 2008.After winning the Lifetime Achievement Award in Translation Culture (2010) from the Translators Association of China,Xu’s EnglishXixiang jiwas published again in 2012 under “Project for Translation and Publication of Chinese Cultural Works” (中国文化著作翻译出版工程项目).His 2012 edition remains identical to his 2000/2008 version in text but substantially differs in paratexts.The most significant paratextual variations include an assertive personal profile,abundant press compliments,and a confident introduction of translation theories of the Chinese school.

Xu’s introductory messages include eight-page Chinese and nine-page English versions,much shorter than West-Idma’s 100-page introduction.Xu justifies his choice of Jin Shengtan’s edition as ST only in the Chinese preface.Besides identifying the Jin’s edition as the favorite of most Chinese literati,he quotes the well-known drama theorist Li Yu (ca.1611-1680),who credits Jin Shengtan with helping establishXixiangji’s esteemed reputation with powerful argumentation (Xu,2008,p.18).From Xu’s lengthy citation of Jin’s remarks onXixiang ji’s theme,love verses,and writing style,his personal preference for Jin Shengtan and his edition is telling.Xu’s ST choice is at least partially guided by his own sentiment and aesthetics.Concurrently,one can see the affinity between Xu’s beautifying principle of translation (Xu,2012,p.349) and Jin’s refining edition.

While Xu does not explicitly state his translation purposes or approaches as other retranslators do,he definitely makes efforts to introduce this masterpiece to the Western world by highlighting the uniqueness of Chinese romance and comparing it to Shakespeare’sRomeo and Juliet.He takes in Jin’s view on the development of Chinese romance,from the earliest Chinese love poems inTheBook of Poetry(诗经) up to those inXixiang ji,considering the symbolic narration of eros in the latter as unique in China and even in the world (Xu,2008,pp.21-22).With specific correlated examples,Xu traces the evolution of love theme in Chinese literature from “implicit and suggestive” to “explicit and symbolic”; while the female being attracted to the male more by his literary talent than his physical strength (ibid.,pp.30-31).In comparison to the world-famous English play,Xu states thatXixiang jiis “as well-known in China as Shakespeare’sRomeo and Julietin the West,yet it was written about three hundred years earlier […]” (ibid.,p.27).He seems to subconsciously set China apart from the West,hinting that the former is more advanced in terms of production timeline.To shorten the distance for Western readers,he bridges the gap between those two plays by affirming their similar linguistic patterns in terms of prose narrative and verse lyrics.He compares some love verses of the two plays and comes to such a conclusion:Chinese lovers are more reticent while Western pairs are more outspoken.Both share the same theme of conflict between love and family honor,but while the Chinese drama ends with reconciliation that preserves both love and honor,the English play ends in the death of the lovers in order for the two opposing households to reconcile (ibid,pp.34-35).Xu furthers his Chinese preface with “the East use culture to solve conflict while the West use violence” (ibid.,p.25),a statement unfound in his English version.Xu’s approach to comparative literature,old-fashioned or not,represents his painstaking effort to elevateXixiang jito or above the status ofRomeo and Juliet.By illustrating China’s prolonged literary tradition of romantic love and comparingXixiang jito a Shakespearean play,Xu reveals his “authorial intention” (Batchelor,2018,p.12).

For a prolific translator like Xu,one can easily draw on his other writings and interviews for a fuller and clearer picture of his purposes and approaches to retranslation.In the Chinese preface of the 2000/2008 edition,Xu points out the prose lyrics employed in Hsiung’s and West-Idema’s translations and the apparently more demanding rhymed libretto in his retranslation.To the same end,in his Chinese preface of the 2012 edition,Xu quotes Lin Yutang’s critique that Hsiung’s translation is sufficiently accurate but insufficiently poetic (2012,p.233),implying his improvement in terms of poetic quality.In a 2013 interview,Xu unambiguously remarks that his translation was superior to Hsiung’s with an example in which his translation reveals the hidden ST meaning and adds musicality.He also makes a clear statement of his lifelong effort to surpass the previous translations in one way or another (Tian,2013).In the same interview,as well as in a number of other writings,Xu reiterates that literary translation for him is an art of creating beauty in meaning,and so he adopts the method of “recreation”,or searching for the best words,when equivalence is unreachable (Liu,2018; Xu,2012,p.345).Likewise,Xu’s purposes of translation,implicit in his introductory message of the 2000/2008 edition but explicitly expressed in various other sources,include the creation of beauty and a commitment to promote and convey Chinese culture to the world; this is a lifelong mission and “Chinese dream” for him (Gong,2017; Xu,2015).He believes that the beauty of Chinese culture “will contribute to making the world a better place” (Liu,2018).

Different from the other two full-fledged retranslations for readers,Shen’s is a script translation for stage performance,which may be viewed as between translation and adaptation,as it is shortened for target theatergoers.Shen demonstrates himself as a well-informed scholar of Chinese drama and theater,as shown mainly in his “Director’s Message” of the production pamphlet.He firstly presents a full-page message in English,starting from the origin ofXixaing ji,the reason for his choice ofchuanqiopera genre,to the reasons for foregoing classical or original music and how their young company members selected the popular melody for the libretto.It is followed by a half-page message in classic Chinese condensed from the English one.In fact,while most Singaporeans are bilingual and English is the dominant language,few can understand classic Chinese.Shen’s self-translation from English to classic Chinese could be a gesture to display his erudition and ability with classic Chinese in addition to his specialty in drama and theater,signifying his credibility in reinterpreting this classic drama.

Unlike Xu’s gentle and implicit style of writing,Shen makes his purpose plain and forceful.He declares that he will offer his audiences the genuine theatergoing experience of pre-modern China.He aims to representXixiang jias a popular theater as in its glorious past,both entertaining and full of vitality.In his own words (Shen,2008a,p.2):

I wanted anauthentic experienceof golden-age Chinese opera for the audience,meaning that a modern theatergoer may enjoy the show as a Ming Chinese did 400 years ago.I did not want to present a piece of museum art that is authentic in form,but lacking in both the vitality of contemporary life and the entertainment value that are imperatives in popular theater.

Shen’s purpose statement also sharply contrasts with West-Idema’s.While West and Idema strive to keep the archaic classic Chinese expressions to invite Western readers into the traditional Chinese world,Shen makes efforts to transform the medieval colloquial Chinese into the trendy modern English so as to infuse “vitality of contemporary life” into his stage translation.Though not a professional translator as Xu nor familiar with any translation theory,Shen apparently goes for functional equivalence,taking up a domesticating approach rather than the foreignizing one as West and Idema do.Shen is thus likely to use modern analogy or figurative expression to replace the age-old ones.Shen differentiates his stage translation from “a piece of museum art”,which seems to refer to the West-Idema version and the current Chinese opera house practice.

Shen goes on to justify his adoption of contemporary music,which affects his libretto translation,making it distinct from all the previous versions.One may be inclined to think he would translate libretto to fit intochuanqimusic such askunquwhich is still alive today.However,his claim of following the Ming pattern turns out to be adopting popular music today.He (ibid.) writes:

Classical theatres today were all popular theatres in their times […] In the heyday of Chinese opera,the audience enjoyed music contemporary to their time; Chinese opera then followed popular tunes in a manner comparable to what a modern audience would do in pop concerts.

Music is the soul of Chinese opera.In order for a modern audience to experience Chinese opera in its true performance spirit,modern music—instead of classical music—must be employed.

He legitimizes his adoption of contemporary pop music as a parallel to the practice of Chinese opera in its golden age.Such practice is in line with his previous claim of entertainment value,which,coupled with his so-called “true performance spirit,” could be Shen’s primary purpose.Doubtlessly,his libretto translation requires additional efforts to fit into pop melody.He stresses his intention in his final remark,“the ultimate proof of the effectiveness ofThe West Wingis […] in your actual enjoyment of the show.It is audience approval alone that will decide the appropriateness of this Renaissance attempt,and the popularity of our Renaissance production” (ibid.).Shen’s version is noticeably target-centered and aiming toward functional equivalence.

To further justify his retranslation,Shen (2013) critiques the insufficiency of the prior translations,including those by the well-known ones,such as West-Idema and Xu.While acknowledging the merits of the West-Idema version as the most scholarly and trustworthy version since it was based on the earliest reliable edition of 1498,he also points out some of the misinterpretations and drawbacks that make it unfit for stage performance.He compares a number of examples in West and Idema’s translation to his own,illustrating how the former misses out textual flavors,like “immediacy,intimacy,subtlety,or ambiguity”,necessary for stage presentation to stimulate a response in audience (Shen,2013,pp.184-188).As for the two existing rhymed translations,he harshly criticizes numerous mistranslations by Wells,while forgivingly lists Xu’s as “Xu imitates the dense rhyming scheme ofzajuopera more closely.Most of his textual deviations are explicable by the intense rhyming effort,rather than misreading” (ibid.,p.183).He points out that the major drawback of Xu’s version is using Jin’s edition of 1656 as ST,which he views as a tampered text for removing some essential arias (ibid.).

4.Paratextual Comparison-II:text design and scholarly endorsements

While translators’ introduction reveals “authorial intention”,the text design and additional information are also in line with translators’ purpose to ensure reception of their translated text.This section examines other paratextual features,from book cover and text layout to scholarly endorsements.

The covers and layouts of the three texts are widely different.West-Idema’s cover is a classic style illustration featuring the initiation of romance.Without seeing each other,scholar Zhang,the hero,plays the zither on one side of a garden wall,while Yingying,the heroine,listens attentively on the other side accompanied by her maidservant.Such illustration is in accord with West and Idema’s intention to invite Western readers into a medieval Chinese world of a sophisticated courting ritual.To illustrate the faithful adherence to the Hongzhi’s edition,West-Idema’s text layout goes to the extent of mirroring the original by inserting an illustration into every act of their English version.The page numbers of the ST are meticulously recorded on translation as well.Similarly,West and Idema keep the commercial title of Hongzhi’s edition,rendering it as “Newly Cut,Deluxe,Completely Illustrated,and Annotated” (1995,p.105).

Figure 1.West-Idema’s text cover and page layout

In contrast,there are few illustrations and no footnotes at all in Xu’s text.The book cover does not even list his name as the translator.Instead,the image of the flowing Yellow River is shown,which seems more to do with the well-known perception of the River being the “cradle” of the Chinese civilization rather than any theme or scene from the drama.The relatively large print of “Library of Chinese Classics”above the bilingual title and throughout the pages of the book unceasingly reminds readers of the patron’s visible presence and grand purpose.

Figure 2.Xu’s text cover and page layout

Shen’s performance-oriented text,a production pamphlet including all the libretto translations,is sharply different from the other two.Distinct from the book size and soft-colored cover of the other two,Shen’s work is an A4 size booklet featuring bright red on the front and black on the back.The eyecatching cover centers “The West Wing” in large print.Its subheading,“a renaissance production with modern music and dance,” presents an unconventional version to revitalize the old with the new.It is even more striking to have the Caucasian male dress in classic costume staring at the Asian heroine,below a whole line of repeated italic words of “Saucy! Saucy! Salacious!” Specifically,Shen’s 2008 production had two versions,opera version and dance version.His opera version followed conventional Chinese opera costuming (which was by and large of the Ming style) to practice genre authenticity,just like the hero shown on the cover page.His dance version,however,employed the Tang attire,an attempt at historical authenticity,similar to the heroine’s cover illustration.Red and black are also the main page color inside the booklet,in which all the introductory messages are printed on red pages while the bilingual librettos in white on black pages.All the colored pages come with noticeable shadowing of bamboo patterns.They are in accord with Shen’s intent for his stage version to be both entertaining and authentic,as can be seen by his choice of red,the color of passion and joy for the Chinese populace,and the image of bamboo,a spiritual icon for Chinese literati.

Figure 3.Shen’s text cover and page layout

Other messages are observed in the foreword,chief editor’s preface,and librettist’s note in West-Idema’s,Xu’s and Shen’s version respectively.The West-Idema version presents a 3-page-long foreword by Cyril Birch before their long introduction.Cyril Birch,the translator of another noted classical dramaMudan ting(The Peony Pavilion),is an even more renowned senior professor of Chinese literature and drama.The foreword from such a prominent scholar in the field no doubt enhances its credibility and influence.Birch starts by describing the typical scholar-beauty (caizi jiaren) romance of traditional Chinese drama for about two pages before discussing the fully mature plays in the Yuan Dynasty,among whichXixiang jistands out.He highly acclaimsXixiang jias “a work of consummate literary and dramaturgical skill […] there is a strong likelihood that it has delighted more people than any other play in human history” (Birch,1995,p.xi).Birch elevatesXixiang jito the world level,and comments on its surviving editions in late Ming and early Qing dynasties (1550-1700),the second greatest era for Chinese drama,as advancing in elegance but missing out the original vigor.He approves of West and Idema’s serious scholarship as they base their translation on the edition of 1498 so as to allow us to come closer to the vividness of the Yuan original and to dive into “the vanished culture of the Yuan stage”; for which he regards them as “two of its most distinguished interpreters” (ibid.,p.xii).Birth’s foreword is scholarly itself,highlighting the strength of West-Idema’s ST choice and dedicated scholarship without over compliment or exaltation.

The chief editor’s preface in Xu’s text is sharply different from the above; it is mission-driven,with a strong aim to promote and export Chinese classics and culture to the Western world.Yang Muzhi,the chief editor,represents the sponsor of the translation series from Chinese classics to English,the Library of Chinese Classics (大中华文库),or perhaps more accurately,Library of Great Chinese Texts.It is not hard to note that this edition belongs to a national project under a powerful patron,with all the translated works in the series sharing the same book cover and chief editor’s preface.In accord with the splendid cover,Yang’s bilingual messages are replete with the pride of the greatness of Chinese culture and civilization,though he keeps reiterating mutual learning between China and the West.

The implicit purpose stated in Xu’s introduction becomes rather explicit and vigorous in Yang’s preface.In a somehow sentimental and grandiose prose essay style,Yang starts with the motivation of this cross-century project,having Chinese translators translate the Chinese literary classics so as to introduce “the nation’s greatest cultural achievements” (2008,pp.1-9) to the world.He explains that those translated by foreign scholars often come with plentiful errors for their inadequate knowledge and grasp of Chinese culture and its written language.Yang then accounts for China’s leading rank of world civilization from the 5th to the 15th centuries with numerous anecdotes beginning with rather imposing remarks as,“If mankind wishes to advance,how can it afford to ignore China? How can it afford not to make a thoroughgoing study of its history” (ibid.,p.10).He starts the next section with “The Chinese nation is great” (ibid.,p.2),which is a sentence not seen in the English version.Yet the overall tone of both remains the same.Yang supports such a statement by quoting Paul Kennedy of Yale University that,“Of all the civilizations of the pre-modern period,none was as well-developed or as progressive as that of China” (ibid.,p.12).In conclusion,he reiterates the reason for the grand publication.With China’s accelerating absorption of other countries’ best culture,it is apparent that “both the West and the East need nourishment of the Chinese culture” (ibid.,p.16).He states in the final lines,“Our aim is to reveal to the world the aspirations and dreams of the Chinese people over the past 5,000 years and the splendor of the new historical era in China” (ibid.,p.16).As the representative of state sponsor,Yang’s China-centered statement shows not just his endeavor to promote Chinese culture via literary classics translated by Chinese translators; it inevitably unveils the rising power of China whose influence extends from economy to culture.Yang’s ambition seems a mirror or expansion of Xu’s vision of the Chinese dream.Xu’s text under such a weighty package deserves attention.

In Shen’s version,the librettist’s note serves a similar purpose.Leong Liew Geok points out the multiple challenges in translating classic Chinese libretto into rhymed English lyrics for singability in popular melody.She accounts for her dilemma in translation,rigorous techniques applied for versification,and adoption of metrics,syllable count,and popular music,such as (Shen,2008a,p.4):

The attempt to present Chinese verse in English translation is fraught with challenge.How can one untie literary and poetic language from its cultural contexts?

The lyrics which are sung to pre-existing popular melodies in opera should kindle in the audience some recognition of the original songs,now recast in another mode.It is in the creative interplay of the pre-existing and the currently embodied that the lyrics inThe West Wingare enriched.

Apparently,rhymed libretto translation to fit in popular tune highlights Shen’s text.Leong explains the advantage of singing to popular melodies as the pre-existing lyrics enhances and enriches the translated libretto.Leong’s final remark echoes and strengthens Shen’s assertion that modern music must be adopted for a modern audience to experience Chinese opera in its performance spirit (Shen,2008a,p.2).Comparative study of sample translations centering on libretto helps further clarify and expound retranslators’ stance in liaison with their paratextual features.

5.Textual Comparisons

As mentioned,the three versions are based on three different STs/editions,which vary mainly due to the lingual customs of the time period and the editor’s preference.This section focuses on libretto translation of the rendezvous scene,inspecting how different retranslators deal with the controversial and once forbidden libretto.One of Yingying’s earlier utterances will also be examined to illustrate the language style of the original and to discern how it is edited by Jin Shengtan.

Yingying’s initial response to Zhang’s love letter is delivered to her maidservant Hongniang.Yingying appears to be outraged,claiming a prime minister’s daughter should never be offended by such a letter.The STs and TTs from West-Idema,Xu,and Shen are displayed as follows:

小贱人!这东西那里将来的? ……谁敢将这简帖儿来戏弄我? (Wang,1955,p.96b)

You little hussy! Where did you get this? …Who makes sport of me with such a note? (West & Idema,1995,p.200)

红娘,这东西那里来的?……谁敢将这简帖儿来戏弄我? (Xu,2008,p.204)

Where has this come from,Rose? …Who dare to make fun of me with such a letter as this? (ibid.,p.205)

小贱人! 这书是那里来的? …… 谁敢将缄帖儿来戏弄我。 (Li,2001,p.579)

Bitch! Scarlet,come here youbitch! Littlebitch,where did you get this? … Who dares to harass me with this kind of letter? (Shen,2008b,p.26)

Among the three,Jin edition’s alteration of ST (in Xu’s bi-lingual version) is obvious,replacing Yingying’s swear word with her maidservant’s name,reflected in Xu’s text.While both West-Idema and Xu aim for readers,West-Idema adopts relatively archaic expressions,perhaps to make readers aware of reading a medieval masterpiece.Their diction represents Yingying as an aristocratic lady,who appears elegant even when scolding.Xu takes on a common expression of smooth English.Like the ST,by skipping some vulgar expression,he upholds Yingying’s image as a gentry lady.With basically the same source line as West-Idem’s,Shen conveys it rather colloquially and vigorously to the extent of exaggeration.Shen attends to Yingying’s human side,capable of cursing,of which he renders with the crude modern expression “bitch”,and even has Yingying repeat it three times,which triggers laughter from the audience (Shen,2016).

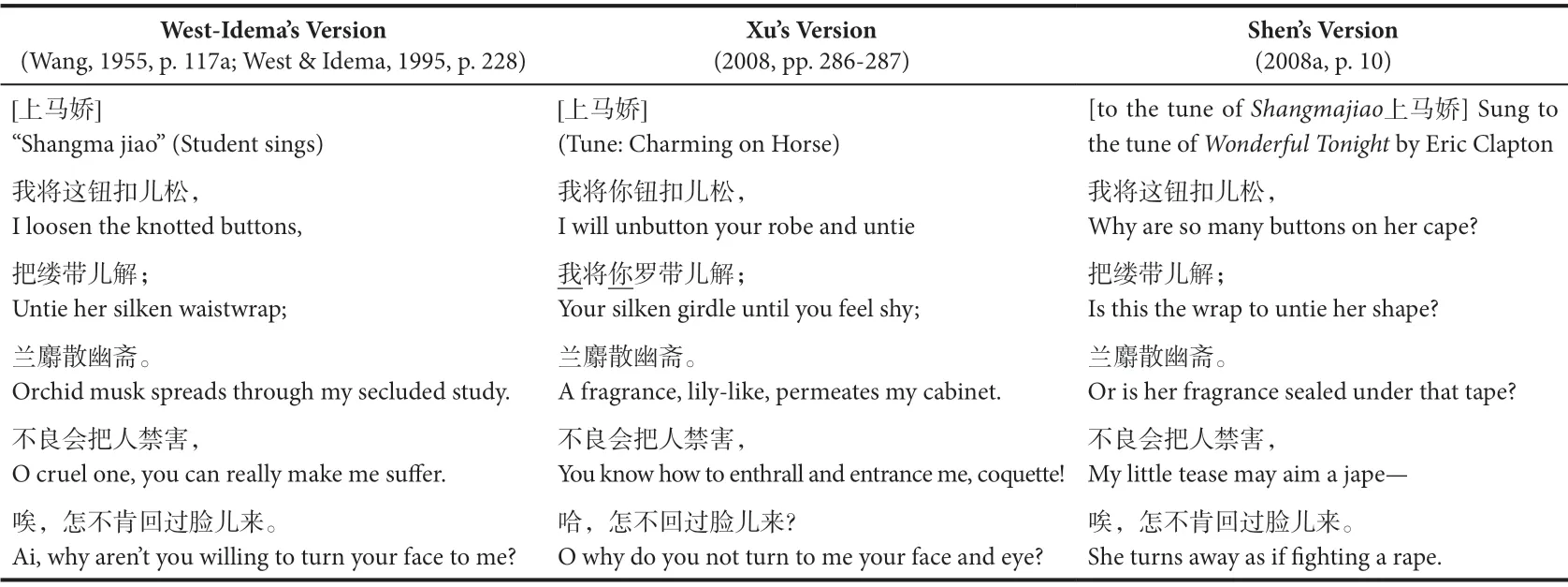

It is a climactic development from Yingying’s display of annoyance,to her night-time visit to scholar Zhang’s room where she throws herself into his embrace.The partial libretto translation of the sex scene to be examined are the episodes showing how Zhang physically approaches Yingying to attain consummation.Zhang sings out his act of undressing Yinging in the following lines,in which the melody is placed at the top,the West-Idema version on the left,Xu version in the middle,and Shen’s on the right:

As shown in Table 1,there is little difference among their STs,except Xu’s which stresses Zhang as the first person singing to Yingying as the second person,by adding “你” (you) in the first line as well as“我” (I) and “你” (you) in the second line.It could be the editor Jin’s intention to accentuate the couple’s intimacy with parallel expressions.Among the three,West-Idema and Xu follow the ST rather closely.West and Idema abide by their conviction of maximum fidelity to the extent of adhering even to the Chinese word order for most of the lines.Xu’s adoption of a limerick’s rhyme scheme,often used to describe taboo transgressions in English verse,shows his adeptness in poem translation.From the sample above,one can tell Xu is up to understandable,elegant English.He does,however,deviate from the ST for the sake of rhyming.For instance,in the second line of Zhang’s singing about his untying Yingying’s girdle,the addition of “until you feel shy” sounds odd and redundant.Apart from the other two sourcecentered translations,Shen’s appears to obviously depart from the wordings and even meaning of the ST,and follows the Chinese operatic end-rhymes system for the sake of singing,which is even stricter than traditional English poetry,as observed by Leong (Shen,2008a,p.4).Instead of Zhang singing out his undressing action toward Yingying as the other two TTs,Shen has Zhang sing out his inner thoughts in the process of undressing.Shen’s translation here appears to correspond to Philip Lewis’s “abuse in translation” (Lewis,2004,p.260),which is best described by Munday as “abusive fidelity” that involves“risk-taking and experimentation with the expressive and rhetorical patterns of language,supplementing the ST,giving it renewed energy” (2012,p.258).Hence,while deviating from the surface meaning of the source text,Shen’s text seems to activate the deeper meaning of source lines to enable the performing action of Zhang and Yingying on stage.For instance,in the final line about Yingying being too shy to turn to Zhang,Shen dramatizes it into Yingying running away from Zhang as if shunning a rape (see Shen,2012a),which displays how desperate Zhang is.

Table 1.

Table 2.

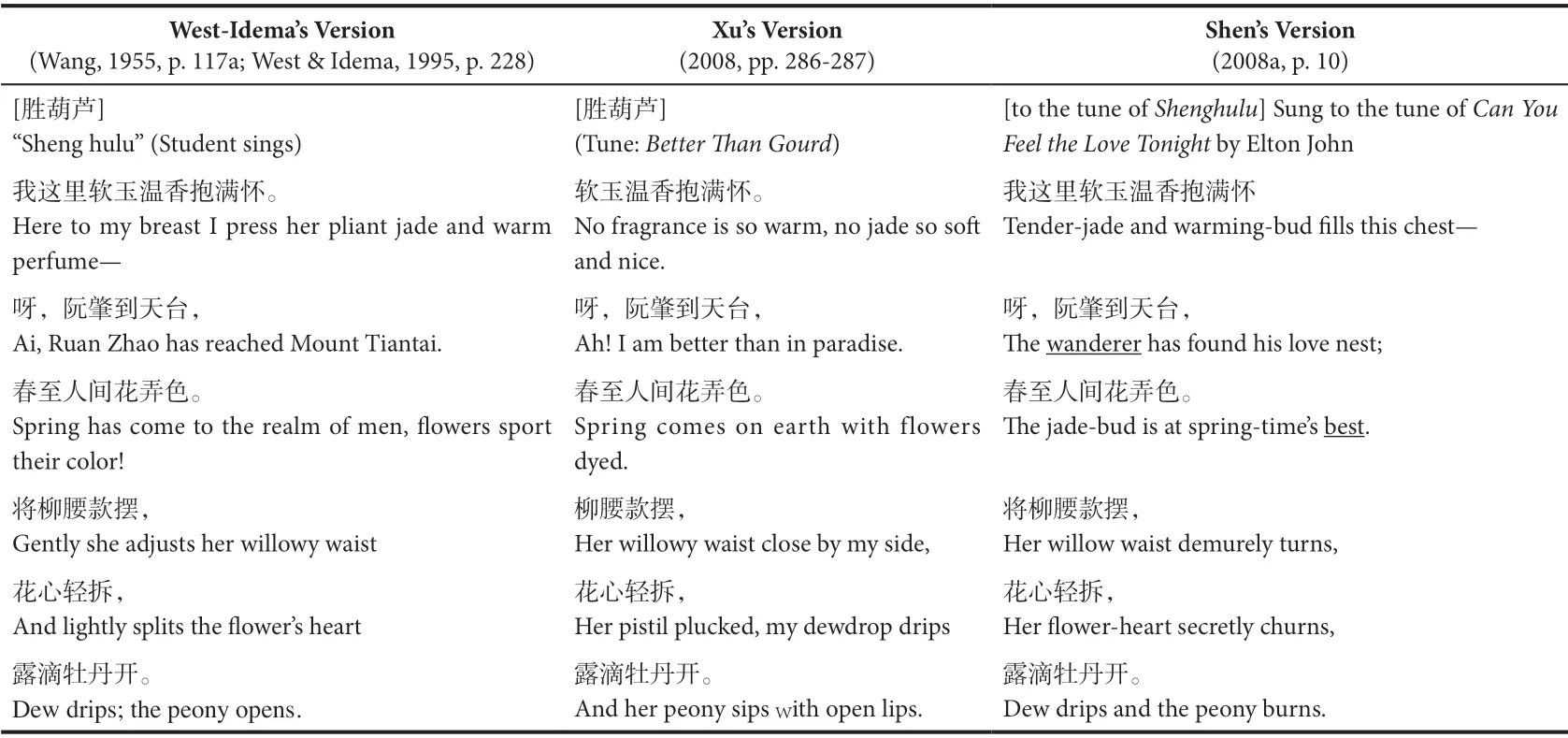

The following stanza proceeds to intimacy,physical embrace,and consummation.The Chinese source libretto is woven with classical allusions and idioms/metaphors that impose a fairly large amount of challenge on the translators in dealing with poetic beauty and accessible meaning.The three divergent libretto translations are displayed below:

This stanza is replete with poetic imagery about Zhang’s further physical advance toward Yingying.The ST of the first line uses the Chinese idiom “soft jade and warm fragrance” (软玉温香) to allude to Yingying’s body.This idiom is rendered with most fluent and poetic English by Xu in spite of its less than direct manner.Compared with West-Idema’s literal rendition of “pliant jade and warm perfume”,Shen-Leong’s “tender-jade and warming-bud”,though deviating from ST on the last word,carries a richer layer of cultural connotation,as the flower bud with fragrance often denotes the beautiful young woman in Chinese culture.In terms of the whole-line translation,West-Idema’s appears more deviating than the other two as Zhang seems to hug Yingying’s belonging objects like jade and perfume rather than her body.Xu’s fluent translation brings out poetic imagery,but leaves out the ST words of embrace (抱满怀).Thus,Shen-Leong’s condensed English lines here seem more accurate and poetic in transmitting the source meaning.

The most challenging classical allusion is the second line,where even most modern Chinese cannot readily comprehend.West and Idema abide by their fidelity principle and render it literally with a footnote to explain the allusion of Mount Tiantai as referring to sexual union.Xu’s text,though representative of Chinese official translation,has abandoned the surface wording of the old Chinese allusion by striking on its intended meaning with modern figurative English expression,“better than in paradise”,which ingeniously hints at Zhang’s climactic experience.In order to grab audience’ instant comprehension,Shen-Leong has made extra efforts to take in key words from the lyric of the music adopted for singing,as has suggested by Leong.Shen’s production team has chosen pop songs resembling the context of libretto as the singing melody to facilitate audience’s connection and speed up comprehension of the English libretto sung on stage.Shen obviously adopts intertextuality by using contemporary analogy to substitute medieval Chinese expression “on the basis of a semantic similarity that relies upon current definitions for source-language lexical items” (Venuti,2013,p.101).For instance,Shen’s stanza above is sung to the tune of popular love song “Can You Feel the Love Tonight” by Elton John,which contains the lyric like,“It’s enough for this wide-eyed wanderer […] It’s enough to make kings and vagabonds believe the very best” (John,2008).Shen-Leong borrows the keyword “wanderer” to refer to Zhang,intending to help the audience recall the context of romantic/erotic love,so does the use of “best” in the following line.

As for the translations of the other lines,they all render the source meaning fairly and adequately though with different strengths.Apart from the first line,West and Idema adeptly and faithfully translate the others with clarity and sufficient poetic imagery.Again,for the sake of rhyming,Xu alters the source meaning to some extent such as to add in Line 4 “close by my side” which is absent in ST,and omit the ST action verb,perhaps to create an image of static beauty before the following motion of love-making.Xu’s translation of the final two source lines alluding to sex with flower imagery,however,seems blatantly graphic.His addition of the third and first person pronouns makes the implicit source imagery explicit.It is also overt,though rather vivid and favored by Xu,with two lines of additional figurative explanation for the final three Chinese characters,which are literally and tersely rendered by West-Idema as “the peony opens”,while vividly and economically put by Shen-Leong as “the peony burns”.Though doubly constrained by rhyme and syllable count,Shen’s text appears to surpass Xu’s for most lines of this stanza in terms of language parallelism and vibrant imagery.

6.Concluding remarks

This comparative study ofXixiang ji’s recent English retranslations from texts to paratexts demonstrates the purpose-driven retranslators’ value creation in their version.It unveils the effect of paratextual elements on translation outcome.As shown,retranslators’ introductions openly reveal their authorial intention,which sets forth their purpose and determine the function of their text.Other paratextual features work together to reinforce the influence and sale of the translated text.The translated texts,on the other hand,disclose certain identity of their translators.For instance,the comparison of sample translations,such as their diction and word choice,can further attest to West and Idema’s primary identity as a sinologist,Xu as a verse translator,and Shen a theater director.

Among the three texts,West-Idema’s stands out as the most scholarly credible and reputable.Their detailed,lengthy introduction,not just their purpose and approach,but also their use of the earliest Hongzhi edition,academic assessment of that edition,and the strong backing from Cyril Birch,all contribute to the standing of their translated text.The classic-style book cover and the attached page number of the original all the more show their dedication to representing this classical Chinese masterpiece as exactly as they can.Jiang Xingyu,a leading expert ofXixiang jiin China,extols the West-Idema’s text as almost flawless and surpassing all previous translations (2009,pp.424,429).Jiang seems more than delighted to findXixiang ji,the object of his life-long studies,to have such international attention as to be translated by top scholars of Chinese literature in the West.He calls West-Idema’s text a significant event for cross-culture communication between China and West,signifying thatXixiang jiis marching forcefully toward the world (ibid.,pp.163,428).

Nevertheless,in an effort to represent the source text as accurately as possible,West and Idema have not rhymed the libretto in their rendition,hence partially missing the original quality.Though they follow the performance-oriented edition ofXixiang jias source text,their foreignization approach creates an estranging style,which is unfit for stage performance.As such,the West-Idema’s text serves well as dramatic literature for ardent Western readers to discover the wealth of classic Chinese drama,but it preserves little features of Chinese opera as a performing art.

Xu’s text is highly promoted by its official patron as part of China’s national project,though the extent of its influence has yet to be measured.The visibility of the patron is most apparent in this version,vividly shown in its paratexts.The chief editor’s remark makes good sense on having Chinese scholars translate Chinese classics so as to avoid lingual or cultural errors made by foreign sinologists.This is true that even West-Idema’s text has some mismatches of wording.Despite the fact that Xu has been a wellrecognized verse translator,his retranslation receives inadequate academic attention.This might have much to do with his chosen ST of the Jin edition.Nevertheless,for the common reader who wishes to glance the beauty of this classical drama,Xu’s text could be an adequate choice.Xu’s translation principle of creating beauty is by and large evident in his libretto translation.There is one positive overseas comment from Minerva Press,London,printed in the back cover of Xu’s 2012 edition as follows:“Romance of the Western Bowertranslated by Professor Xu might vie with Shakespeare’sRomeo and Julietin appeal and artistry.” This perhaps is the most acclaimed international review of Xu’sXixiang jiretranslation.

Shen’s text may hardly be compared with West-Idema and Xu’s in terms of length and state patron promotion.However,Shen is innovative and audacious to be the first one to translate and transformXixiang jion English stage.His credentials and innovative audacity are vividly shown in the paratexts of his production pamphlet,forcefully displaying his expertise in classical Chinese drama and theater with a justification of adopting pop music.Though often manipulating the text for dramatic effect and overtly pandering to the audience’s tastes,Shen’s translated text is not at all inferior and even at times superior to the other two versions.This is partially evidenced in some of his libretto translation which not only adheres to singability,but also conveys layers of cultural and literary imagery.Shen’s production was well received in Singapore,as reported in local newspapers with applauding titles (Hsiung,2012,p.50).The fusion of old Chinese art and Western fashion appeals to local critics.Drama critics in China,nonetheless,are ambivalent about Shen’s production,questioning his adoption of Western pop music and the explicit stage performance of sexual scenes (ibid.,p.51),usually skipped on stage.Positive comments from scholars of China include appreciation of his innovative libretto translation that captures classical qualities(Shen,2012b,p.198).

The three English texts demonstrate the retranslators’ endeavor with their specific individual purpose to present the medieval Chinese dramaXixiang jito English readers and audiences.Though having different strengths and limitations,it is fair to say that West-Idema’s by and large foreignized text provides great service to serious readers and scholars,while Xu’s fluent modern English text is suited for the average reader.As for Shen’s rather colloquial and domesticated stage version,though frowned upon by some Chinese critics,appears to be most appreciated by younger English-speaking audience.

The comparative studies of three retranslations ofXixiang jifrom 1995 to 2008 incidentally map the trend of translation studies,from source-centered to target-centered,and from drama translation to theater translation.Significantly,they reveal the infinite potential of this classic Chinese drama as a masterpiece capable of accommodating diverse interpretations and representations.These translated texts,functionally divergent,manifest the afterlife ofXixiang jithat continues to shine in different decades with different lights.

- 翻译界的其它文章

- The Re-narrated Chinese Myth:Comparison of Three Abridgments of Journey to the West on Paratextual Analysis1

- Nominalization and Domestication:Reconsidering the Titles of the English Translations of Pu Songling’s Liaozhai zhiyi

- Transference of Things Remote:Constraints and Creativity in the English Translations of Jin Ping Mei

- Classical Chinese Literature in Translation:Texts,Paratexts and Contexts

- Images of Chinese Women in the Hands of Translators:A Case Study of the English Translations of Pu Songling’s Liaozhai zhi yi

- Paratexts in the Partial English Translations of Sanguo yanyi