Depressive symptoms and their associated factors in heart failure patients

Deng-Xin He*, Ming-Hao Panb

aSchool of Nursing, Hubei University of Chinese Medicine, Wuhan, Hubei 430065, China bSchool of Medicine, Xinyang Normal University, Xinyang, Henan 464000, China

Abstract: Objectives: Depressive symptoms are common in heart failure (HF) patients and they may exacerbate the progression of HF. Thus,identifying associations with depressive symptoms is essential to develop effective interventions to alleviate patients’ depressive symptoms. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the factors related to HF patients’ depressive symptoms.

Keywords: depressive symptoms • dispositional optimism • functional capacity • heart failure • social support

1. Introduction

Depressive symptoms are common in patients with heart failure (HF).1It has been found that the prevalence rates of depressive symptoms range from 24% to 42% in patients with HF,2and 58% in hospitalized older patients with HF.3Depressive symptoms are demonstrated to be associated with poor prognosis in patients with HF.4,5It was found that both depressive symptoms in baseline and worsening depressive symptoms in 1-year followup increased the risk of HF patients’ death or cardiovascular hospitalization.6,7Similarly, depressive symptoms could significantly predict increased all-cause mortality during 1-year follow-up.8Furthermore, the hazard was found to differ over time with depressive symptoms posing a little risk for HF patients’ mortality in the first year, but the greater risk in the second and third years of follow-up.9In addition, depressive symptoms were reported to be associated with reduced quality of life in patients with HF.4,5,10Therefore, it is essential to understand the factors associated with depressive symptoms to develop effective interventions to relieve HF patients’depressive symptoms.

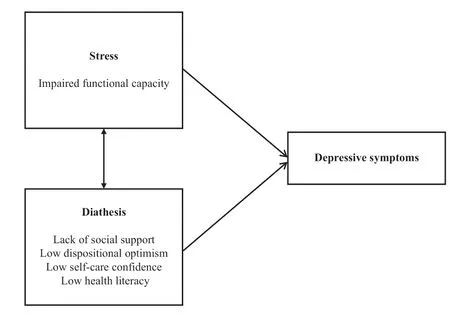

Diathesis-stress theories provide the basis for developing frameworks for investigating potential factors of depressive symptoms.11Diathesis, which could be considered as vulnerability, includes cognitive and psychosocial factors that cause individuals to be vulnerable to depressive symptoms in response to stress. Stress is defined as “environmental events or chronic conditions that objectively threaten the physical and/or psychological health or well-being of individuals of a particular age in a particular society”.12Diathesis-stress theories suggest that diathesis and stress contribute to the development of depressive symptoms, and particular stress may interact with diathesis. Thus, some specific diatheses and stress may cause HF patients to be vulnerable to depressive symptoms. Based on diathesis-stress theories, we operationalized impaired functional capacity as potential stress, lack of social support, low dispositional optimism, low self-care confidence, and low health literacy as potential diathesis (Figure 1).

It is critical to identify the potential factors related to HF patients’ depressive symptoms because this would provide referential information for the development of interventions to relieve their depressive symptoms.Thus, the current study aimed to assess the associations between potential factors and HF patients’ depressive symptoms. We inferred that impaired functional capacity, low social support, low dispositional optimism,low self-care confidence, and low health literacy were associated with depressive symptoms in patients with HF and impaired functional capacity may interact with potential diatheses.

Figure 1. The conceptual model guiding this study.

2. Methods

2.1. Design and procedures

This study was designed to examine the factors associated with depressive symptoms in patients with HF.Potential patients were recruited from a universityaffiliated hospital by convenience sampling. A trained research assistant assessed whether patients were eligible and obtained written consent from eligible patients.After patients completed the questionnaires provided,the assistant checked the questionnaires to ensure accuracy and integrity.

This study conforms to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Researchers recruited eligible patients in three cardiovascular units of a large, university-affiliated hospital in Shandong province, China,from November 2016 to June 2017. Patients who (a)had HF diagnosed, (b) were aged 18 years, (c) were within New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II–IV, (d) spoke or read Chinese, and (e) were willing to participate in this study, were recruited. Patients who (a) had serious comorbidities or mental disorders,(b) had severe hearing or visual impairments that meant they were unable to communicate, or (c) were unable to understand the questionnaires, were excluded. Written consent was obtained at the beginning of the investigation. To ensure the accuracy and integrity of the questionnaires, researchers checked the questionnaires after the patients finished completing them. Later, researchers collected patients’ demographics and clinical characteristics by reviewing medical records or interviewing patients. Three hundred and twenty-one eligible participants with completed data were included in this study.

2.2. Participants

All of 321 patients in the original study were included in this study. The participants had a mean age of 63.6 ± 10.6 years. Of the 321 patients, nearly half(48.6%) were female. The majority (85.7%) of the patients were married or living with a partner, and 27.4%earned <1000 RMB (approximately 148 American dollars) monthly. In all, 63% of the patients were classified into NYHA functional class II, with a higher level of NYHA class, indicating more severe HF. The median of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-pro BNP)was 2384.6 pg/mL. The details are shown in Table 1.

The target number of patients was 234 conducted by G*Power software Version 3.1 based on a moderatef2effect size of 0.15, α of 0.05, and a power of 0.95.13A total of 321 participants were enough for the sample size requirement in this study.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Depressive symptoms

The Chinese version of the Depression Subscale of Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D) was used to measure patients’ depressive symptoms.14This scale contains seven items that use a 4-point scale.The total score of this scale ranged from 0 to 21, with a higher score indicating more severe depressive symptoms. Patients whose scores are >7 were considered to have depressive symptoms. The Chinese version of HADS-D is suitable for patients with HF, with Cronbach’s α of 0.83.15The Cronbach’s α of HADS-D was 0.75 in our study.

2.3.2. Functional capacity

Functional capacity was measured using the Chinese version of the Duke Activity Status Index (DASI) in patients with HF.16The DASI contains 12 items that assess whether the patients can do the activities. The total score for DASI was computed according to 12 items and their weighted scores. It ranges from 0 to 58.2, and a lower score indicates a poorer functional capacity. In HF patients, the Chinese version of DASI is reliable for HF patients, with Cronbach’s α of 0.86.17The Cronbach’s α of DASI was 0.71 in our study.

2.3.3. Social support

Social support was assessed using the Chinese version of The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS).18The MSPSS contains 3 dimensions and 12 items. Each item uses a 7-point scale. The total score of this scale ranges from 12 to 84, and a lower score indicates a lower social support. The Chinese version of MSPSS is reliable for HF patients, with Cronbach’s α of 0.91.19The Cronbach’s α of MSPSS was 0.84 in our study.

2.3.4. Dispositional optimism

The Chinese version of the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R) scale was used to measure patients’dispositional optimism.20The LOT-R contains 6 items which are rated on a 5-point Likert scale. According to the recommendation of scale developers, this study used this scale as a unidimensional scale. In this study,after deleting an invalid item, the total score ranges from 5 to 25, with a lower score indicating less dispositional optimistic. The Chinese version of LOT-R is with Cronbach’s α of 0.72.21The Cronbach’s α of LOT-R was 0.61 in our study.

2.3.5. Self-care confidence

Patients’ self-care confidence was measured by the Chinese version of the subscale of self-care confidence in the Self-care of HF Index.22The scale comprises six items with four options to assess patients’ perceived confidence to engage in self-care behavior in the last month. The total score was standardized to a 0–100 range, with a lower score indicating lower confidence in the ability to engage in self-care behaviors. The Chinese version of the subscale of self-care confidence in the Self-care of HF Index has been reported to be with Cronbach’s α of 0.87.23The Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.63 in our study.

2.3.6. Health literacy

The Chinese version of the Health Literacy Scale for Patients with Chronic Disease (HLS) was applied for assessing HF patients’ health literacy.24This scale was developed from Health Literacy Management Scale.25The HLS consists of 24 items that assess the personal capacity to obtain, understand, and use health information. Each item uses a 5-point Likert scale. The total score for HLS ranges from 24 to 120, and a lower score indicates poorer health literacy. HLS has been reported to be valid and reliable, and the Cronbach’s α for HLS in Chinese patients ranges from 0.89 to 0.93.24The Cronbach’s α was 0.88 in our study.

2.3.7. Demographic and clinical characteristics

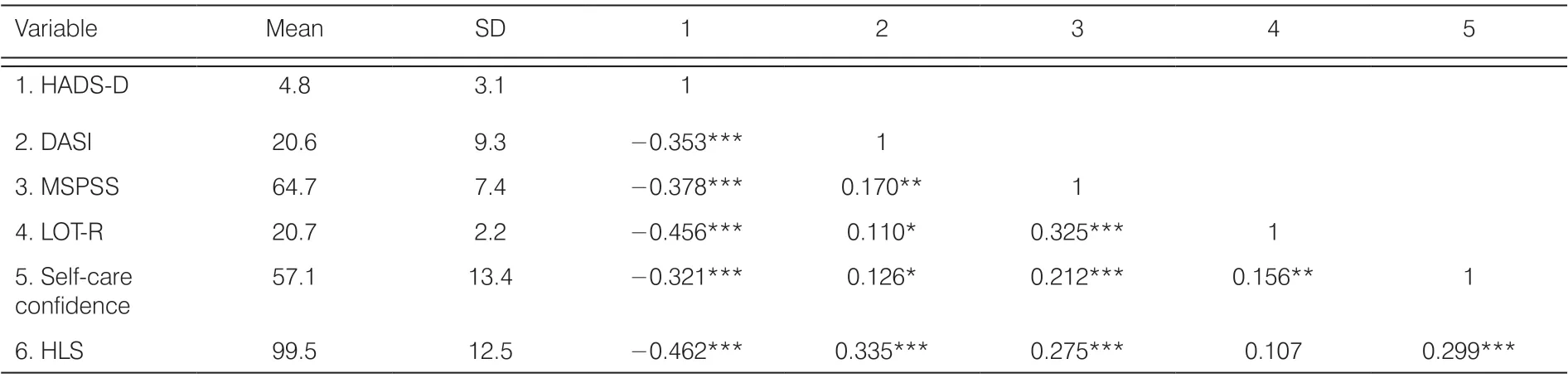

Demographic information included gender, age, education ( SPSS software for Windows version 20.0 (IBM Corp,Armonk, New York) was used for data analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the sample. Independent groupt-tests and one-way analysis of variance were used to assess the difference in HADS-D score in demographic and clinical characteristics; Pearson correlation was used to assess the associations among continuous variables. To assess the interaction effects, the interaction terms between potential stress and potential diatheses (DASI * MSPSS, DASI * LOT-R, DASI * self-care confidence, DASI * HLS) were generated. To control the effects of covariates on the study results, stepwise multiple linear regression with an entry criterion ofP< 0.050 and exit criterion ofP> 0.100 was used to assess the potential factors associated with HADS-D score. The independent variables included gender, age, education, employment, marital status,residence, income, left ventricular ejection fraction,NYHA class, NT-pro BNP level, previous hospitalizations due to HF, disease duration, comorbidities, BMI,DASI, MSPSS, LOT-R, self-care confidence, HLS,DASI * MSPSS, DASI * LOT-R, and DASI * self-care confidence, DASI * HLS. AP-value of 0.050 was considered as significant. In this study, 58 (18.1%) patients had depressive symptoms. Higher HADS-D scores were found in patients whose education were less than high school(P< 0.001), who were unemployed (P= 0.018), who were single, divorced, or widowed (P= 0.046), who were living in an urban area (P= 0.002), whose income was <1000 RMB per month (P= 0.001), whose hospitalizations for HF were over three times (P= 0.002), and whose HF duration were over 6 months (P= 0.028). Age(r= 0.110,P= 0.048) and NT-pro BNP level (r= 0.135,P= 0.015) were positively correlated with HADS-D score.The HADS-D score had significant differences among NYHA class groups, and BMI groups. The details are shown in Table 1. Mean scores for study variables and the correlation coefficients are shown in Table 2. The mean HADS-D score was 4.8 ± 3.1. Scores for functional capacity (r= −0.353,P< 0.001), social support (r= −0.378,P< 0.001), dispositional optimism (r= −0.456,P< 0.001), self-care confidence (r= −0.321,P< 0.001), and health literacy(r= −0.462,P< 0.001) were negatively correlated with the HADS-D score. A stepwise multiple linear regression identified that scores for functional capacity (β = −0.043,P= 0.007),social support (β = −0.047,P= 0.016), dispositional optimism (β = −0.513,P< 0.001), self-care confidence(β = −0.032,P= 0.002), and health literacy (β = −0.076,P< 0.001) were independently associated with the HADS-D score. In addition, the interactive term between scores for functional capacity and dispositional optimism (β = 0.017,P= 0.007) was significant. This model accounted for 45.2% of the variance in HADS-D score.There was no multicollinearity issue in this study (tolerance was >0.1, and the variable inflation factor was<10). The details are shown in Table 3. In the present study, we examined the possible factors associated with HF patients’ depressive symptoms.Consistent with a previous study, we found that depressive symptoms were more prevalent in HF patients than in the general population.26Functional capacity,social support, dispositional optimism, self-care confidence, and health literacy were negatively connected to depressive symptoms; these findings add to the existing literature. In the present study, 58 (18.1%) patients had depressive symptoms. In HF patients, there is a variation in the reported prevalence of depressive symptoms.Similar to our results, an observational study showed that 22.4% of HF patients had depressive symptoms.27However, Fan and Meng28reported that the prevalence was 44.1% in this population, which was higher. The differences in the prevalence across studies may be attributed to the differences in the severity of HF. Patients with more severe HF, as indicated by a higher NYHA class,have been reported to have a higher risk of depressive symptoms.29The proportion of patients with an NYHA class of β or χ was much higher (55.6%) in the study by Fan and Meng than in this study (37.1%) and in the study (33.3%) by Graven et al.27This may explain the relatively low prevalence in our study. In this study, functional capacity was negatively related to depressive symptoms. Consistently, it was reported that functional capacity was related to HF patients’ depressive symptoms.30Further support is provided by previous studies which suggested that exercise training improved HF patients’ functional capacity and clinical outcomes, and reduced patients’ depressive symptoms.31,32Our finding adds evidence concerning the negative association between functional capacityand depressive symptoms, and indicates that preventing HF patients’ functional capacity from decreasing may be helpful to relieve depressive symptoms in HF patients. Table 2. Mean scores and correlation coefficients between potential influencing factors and HADS-D (n = 321). Table 3. Stepwise multiple linear regression analysis of HADS-D score (n = 321). Our study showed that HF patients with lower social support had more severe depressive symptoms. Similarly, in a review of 15 studies, 11 studies showed a consistent result that lower social support was significantly related to HF patients’ depressive symptoms.33Family members are key sources of social support for Chinese HF patients. However, elderly patients with HF may lack support from their young family members due to the changes in society and economy in China, wherein young people relocate to more developed cities for work or study, leaving their older family members at home.34Our result suggests that improving HF patients’ social support be a potential target of intervention to alleviate depressive symptoms. In this study, low dispositional optimism was related to depressive symptoms in patients with HF. Similarly,two other studies showed that optimism was significantly related to depressive symptoms in the general population and depressive population.26,35Our study adds evidence to confirm the negative relationship between dispositional optimism and depressive symptoms in patients with HF. As a group-based optimism training program has been proved to be beneficial to cardiac patients,36improving dispositional optimism may reduce depressive symptoms in HF patients. This study showed that HF patients with a lower level of self-care confidence had more severe depressive symptoms. Similarly, it was reported that interventions that self-care education could reduce depressive symptoms in patients with thalassemia.37Our study provides a novel view that HF patients’ low self-care confidence is important in the development of depressive symptoms.The present study suggested that interventions aimed at promoting HF patients’ self-care confidence, such as motivational interviewing or cognitive behavioral interventions, may be beneficial for reducing their depressive symptoms. We found that lower health literacy was related to more severe depressive symptoms in HF patients. Our finding was supported by a meta-analysis of 23 studies,38which revealed that health literacy was correlated with mental quality of life. The current study expands our understanding that low health literacy may be a potential diathesis to develop depressive symptoms when patients confront HF. Strategies, such as providing health-related comic books, focused on improving health literacy may contribute to relieving HF patients’depressive symptoms. It is worth noting the interaction effect between functional capacity and dispositional optimism on HF patients’ depressive symptoms. Our study indicated that HF patients with lower dispositional optimism may have more depressive symptoms when their functional capacity decreased. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the interaction effect on HF patients’depressive symptoms, which adds evidence to the existing literature. Several limitations of this study should be recognized. First, the current study was a secondary data analysis of a cross-sectional study, the primary purpose of which was not to explore the possible factors associated with depressive symptoms. Perhaps choices were limited to the factors measured in the original study. For instance, treatment for depression was not available,but it was a covariate in this study. Further intervention studies are warranted to confirm the causality. Second,in our sample, most of the patients were classified as NYHA class II, which may limit the potential to generalize our results to the entire HF population. Future studies need to be conducted with a more representative sample. Third, this study used self-reported measures.Thus, potential reporting bias may threaten the evidence of our findings, despite the good reliability and validity of the instruments. Our study makes sense for clinical practice because it provides referential information for the development of interventions to relieve HF patients’ depressive symptoms. Our findings suggest that healthcare providers should take these factors, including functional capacity, social support, dispositional optimism, self-care confidence, and health literacy, into consideration to develop effective interventions to relieve their depressive symptoms. In conclusion, as many HF patients have depressive symptoms, healthcare providers should pay attention to early detection and management of depressive symptoms to improve HF patients’ outcomes. Moreover,impaired functional capacity, low social support, low dispositional optimism, low self-care confidence, and low health literacy were associated with more severe depressive symptoms in patients with HF. Therefore,interventions targeted at improving the above factors may result in a reduction of depressive symptoms in HF patients. Ethical approval Ethical issues are not involved in this paper. Conflicts of interest All contributing authors declare no conflicts of interest.2.4. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of HADS-D score by sample characteristics

3.2. Mean scores and correlations between potential influencing factors and HADS-D

3.3. Stepwise multiple linear regression analysis of HADS-D score

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Frontiers of Nursing的其它文章

- Predictors of nurse’s happiness:a systematic review

- Redefining the concept of professionalism in nursing: an integrative review

- Clinical nursing competency assessment:a scoping review

- Moderating effect of psychological resilience on the perceived social support and loneliness in the left-behind elderly in rural areas†

- Effects of progressive muscular relaxation and stretching exercises combination on blood pressure among farmers in rural areas of Indonesia: a randomized study†

- Visualization analysis of research“hot spots”: self-management in breast cancer patients†