Risk of venous thromboembolism in children and adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Xin-Yue Zhang, Hai-Cheng Dong, Wen-Fei Wang, Yao Zhang

Abstract

Key Words: Thromboembolism; Children; Adolescents; Ulcerative colitis; Crohn’s disease; Meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a digestive system disorder characterized by chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract[1 -5 ]. The two common manifestations of IBD are ulcerative colitis (UC)and Crohn’s disease (CD)[1 -5 ]. The pathogenesis of IBD involves a complex interaction between the host genetics, external environment, gut microbiota, and immune responses[6 -8 ]. The incidence of pediatric and adult IBD is rising steadily worldwide, especially in developed countries[9 -11 ]. Approximately 25 %of patients with IBD are diagnosed before the age of 18 years[12 ,13 ]. Furthermore, 4 % of pediatric IBD occur before the age of 5 years and 18 % before the age of 10 years, peaking in adolescence[7 ].

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a potentially severe medical condition with a high recurrence rate[14 ,15 ]. IBD is a high-risk factor for the occurrence and development of VTE in adults[16 ,17 ]. Routine VTE prophylaxis is recommended for IBD patients during hospitalization[1 ,18 -20 ]. Pediatric patients with IBD also have an increased predisposition to develop VTE, including deep venous thrombosis(DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), although the available evidence is of lower quality[21 ,22 ]. The etiology of VTE in IBD is multifactorial and not well defined. It involves the cross-talk between coagulation and inflammation[23 ,24 ]. IBD-associated inflammation causes a hypercoagulable state,leading to systemic thrombotic events and local microthrombi in the vessels of the inflamed intestinal mucosa[25 ,26 ]. Pediatric IBD patients exhibit various clinical features, including disease location and severity, endoscopic appearance, histology, comorbidities, complications, and response to treatment options[27 ]. The reported risk factors for VTE in children with IBD include inherent genetics, ethnicity,gender, infection, parenteral nutrition, surgery, specific therapies, disease history, and increased use of central venous catheters (CVCs; the most common factor)[28 -30 ].

Nonetheless, whether the development of VTE complications in IBD treatment is age-dependent is yet to be clarified. The increased risk of VTE in adult patients with IBD is widely recognized[31 ]. A twoto three-fold increased risk of VTE has been demonstrated in patients with IBD compared to the general population[26 ]. However, less is known about the risk of VTE in child- and pediatric-onset IBD. In recent years, several studies have reported the rising incidence rate of VTE in juvenile patients with IBD,and the related risk factors have been explored[32 -35 ]. Therefore, this meta-analysis evaluated the association between postoperative VTE risk and IBD in children and adolescent populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

According to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews (PRISMA, 2020 ) guidelines, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis. PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science,SinoMed, CNKI, and WANFANG databases were systematically searched for studies published up to April 2021 .

Eligibility criteria

Articles were included if they met the following criteria: (1 ) Investigating the incidence or risk of VTE in children and adolescents with IBD; (2 ) IBD and VTE (DVT, pulmonary embolism; CVC-related thrombosis, intracranial venous sinus thrombosis, portal vein thrombosis, thromboembolic events,intra-abdominal thrombus, and cerebrovascular thrombosis) were confirmed medically; (3 ) language was limited to English or Chinese; and (4 ) RCT, cohort, or database review design.

Publications were excluded if they were: (1 ) Letters, review articles, meta-analyses, case-control, case reports, and experimental animal studies; (2 ) Missing primary data; or (3 ) Full text unavailable.

Search strategy

PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, SinoMed, CNKI, and WANFANG databases were systematically searched for potentially eligible studies published up to April 2021 . The MeSH terms used were as follows: “inflammatory bowel disease”, “Crohn Disease”, “Colitis, Ulcerative” and“Children”, “pediatric*” and “Venous Thrombosis Pulmonary”, “Embolism vein thrombosis”, as well as relevant keywords. The search strategy for PubMed, Embase and Cocharane Central is listed in Supplementary Table 1 .

Data extraction and quality assessment

The selection and inclusion of studies were performed by two independent reviewers in two stages,which included the analysis of the titles/abstracts, followed by a full-text assessment. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. Data including the authors’ names, publication year, study design,country, sample size, mean age, IBD therapy, patient, VTE type, and male percentage were extracted.The quality assessment was performed in duplicate by two researchers independently (xx and xx). The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)[36 ] was used to assess the methodological quality of eligible observational studies.

小米急了,打算拨打报警电话。“滴滴滴……”这时,监控系统突然提示已经定位到阿姆的位置,就在离家不远的小树林里。小米顾不上多想,飞快地向小树林赶去。

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using STATA SE 14 .0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The risk of VTE in IBD was estimated by ES (p) and the corresponding 95 % confidence interval (CI). The available odds ratio (OR) and the corresponding 95 %CI were extracted to compare the outcomes. In addition, the event incidence was relatively small (0 < P < 0 .2 ), and the double arcsine method was also used for data conversion.

Cochran’s Q statistic (P< 0 .10 indicated evidence of heterogeneity) was used to assess heterogeneity among the included studies[37 ]. When significant heterogeneity (P < 0 .10 ) was detected, the randomeffects model was applied to combine the effect sizes of the included studies; otherwise, the fixed-effects model was adopted[38 ]. In addition, sensitivity analyses were performed to identify individual study effects on pooled results and test the reliability of the results.

RESULTS

Literature search and study characteristics

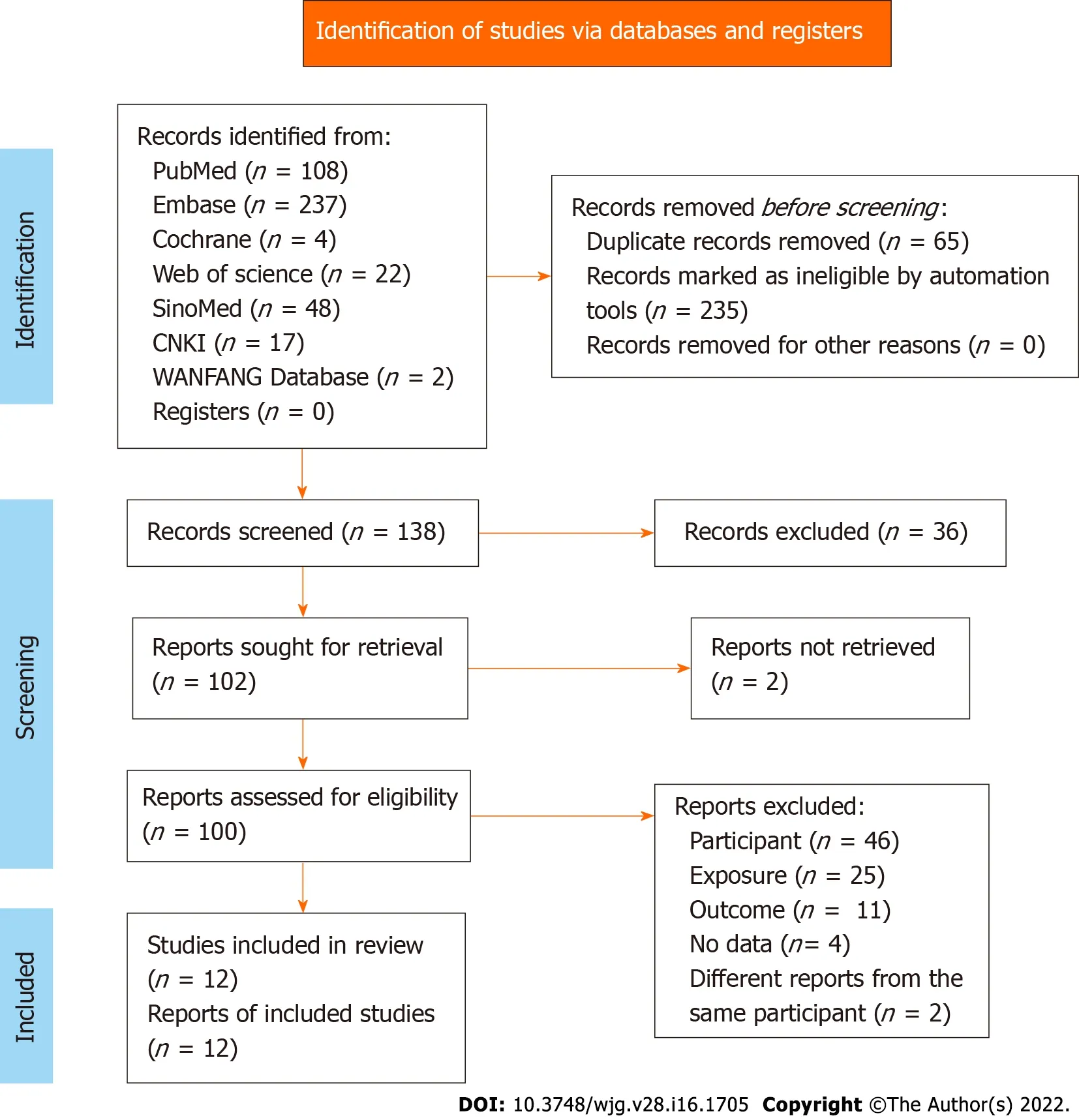

The initial literature database search retrieved 438 studies. The duplicate records and automatically marked ineligible records were filtered out. After screening, 100 reports were assessed for eligibility.Due to insufficient information on participants, exposure, outcomes, and different reports from the same participants, only 12 reports were finally included in this meta-analysis. The study screening flowchart is illustrated in Figure 1 .

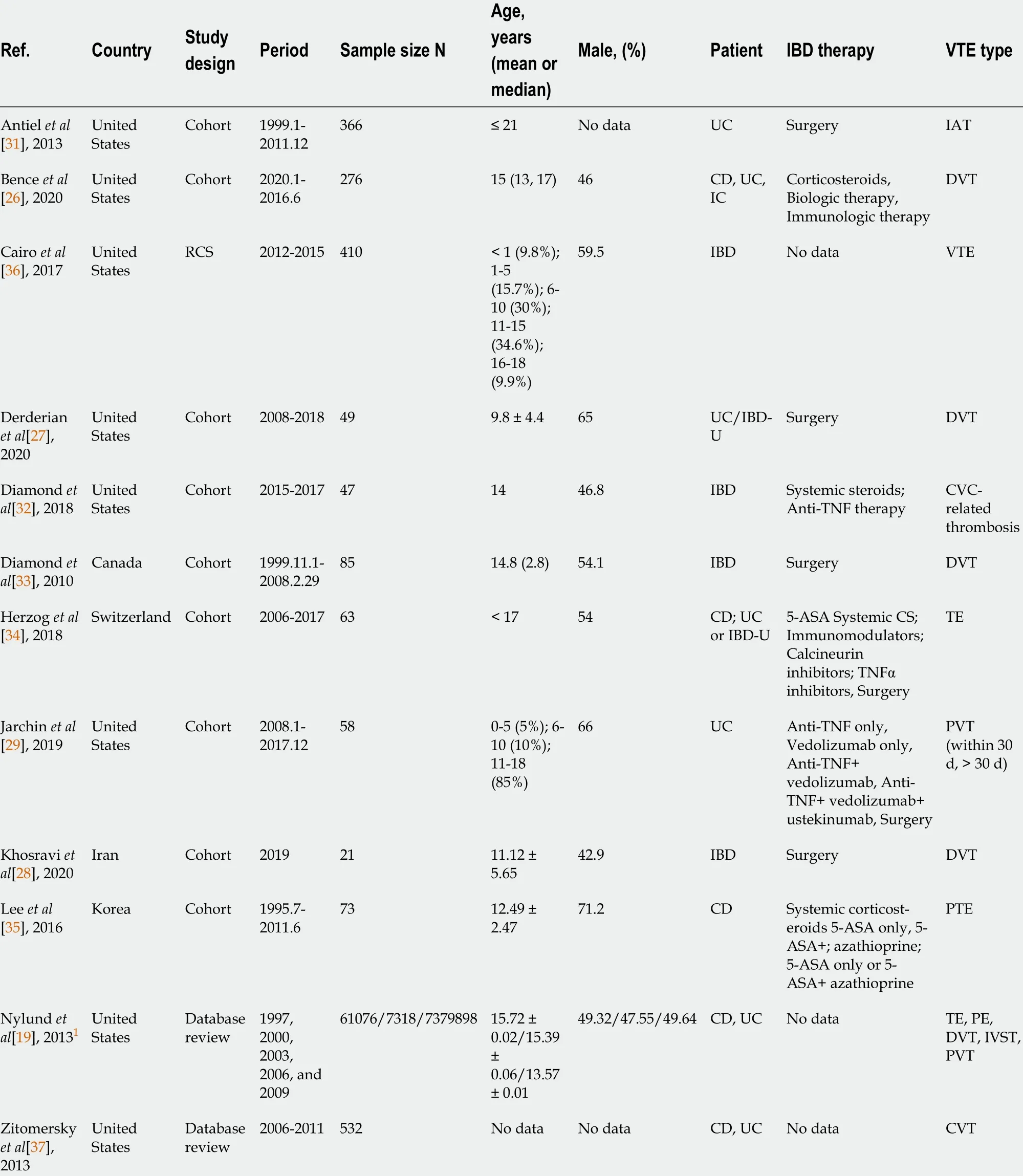

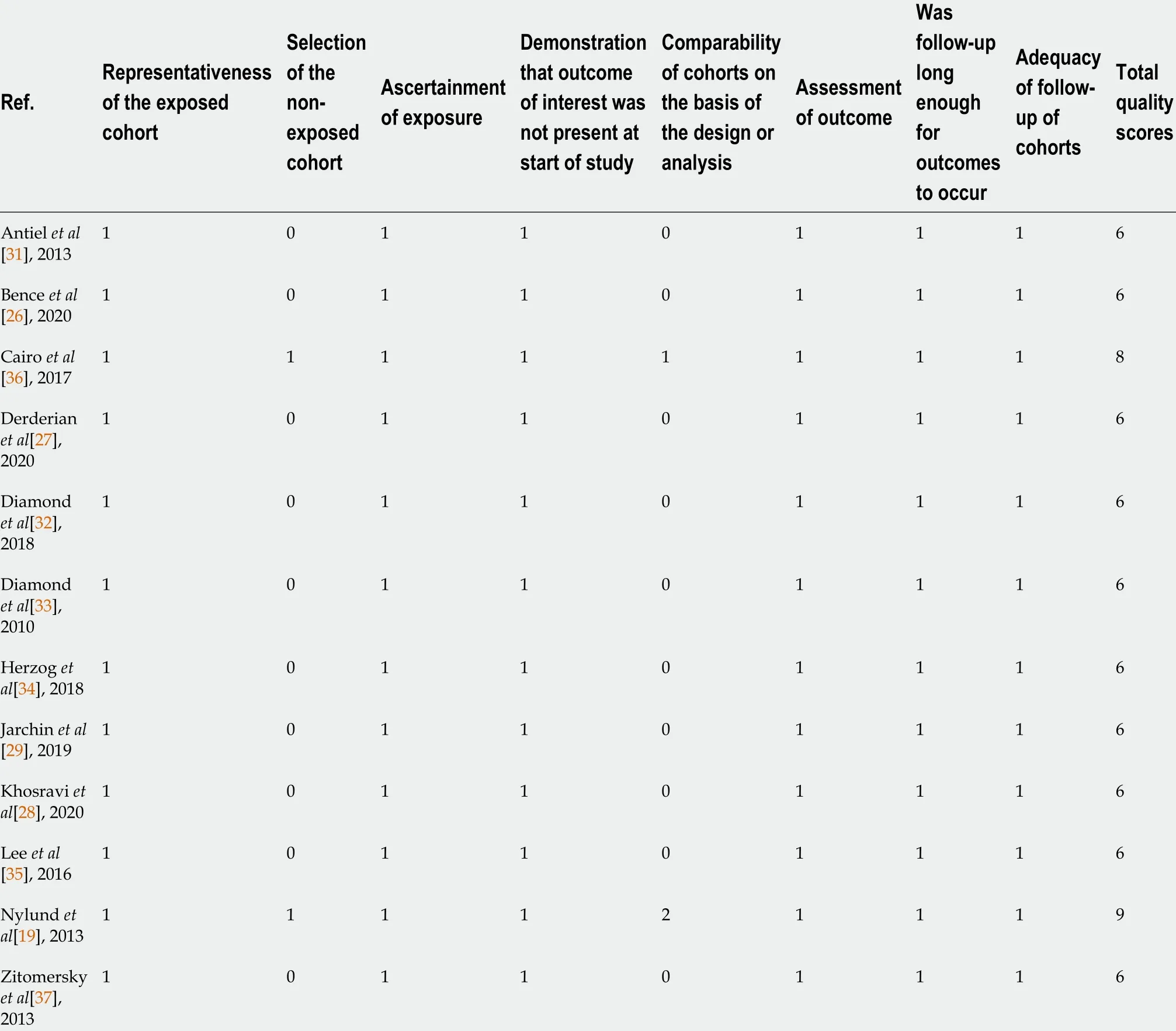

The characteristics of the 12 eligible studies, including nine cohort studies[21 ,27 ,30 ,32 -35 ,39 ,40 ], one RCT[28 ], and two database reviews[25 ,41 ], are listed in Table 1 . These studies encompassed 7450272 IBD patients. Eight studies were carried out in the United States, and the others were performed in Canada,Switzerland, Iran, and Korea. The IBD patients had a mean age of < 1 -21 years. The proportion of male patients ranged from 42 .9 % to 71 .2 %. The IBD subtypes covered UC, CD, indeterminate colitis (IC), and undefined IBD type (IBD-U). Moreover, various VTE subtypes, including intra-abdominal thrombosis(IAT), DVT, venous thromboembolism (VTE), TE, pulmonary thromboembolism (PTE), intracranial venous sinus thrombosis (IVST), PVT, and cerebrovascular thrombosis (CVT), were investigated. In addition, the confounding factors, including age, sex, hypercoagulable status, CVC, parenteral nutrition,cancer, sickle cell anemia, tobacco use, race/ethnicity, payer status, urban/rural status, hospital region,and length of inpatient stay, were adjusted in various studies. According to the NOS evaluation criteria,the methodological quality score was 6 for 10 studies and 8 and 9 for the other two studies, respectively,indicating low-to-moderate bias (Table 2 ).

Table 1 Characteristics of the included studies: ulcerative colitis patients and Crohn’s disease patients

Table 2 Quality assessment

Association between IBD and VTE risk

The association between IBD and the incidence of VTE was assessed in 12 studies. The pooled results showed that the risk of VTE was significantly increased in IBD patients compared to those without IBD (P= 0 .02 , 95 %CI: 0 .01 -0 .03 ). Moderate heterogeneity was detected across the included studies (I2 = 54 .7 %,Pheterogeneity= 0 .012 , Figure 2 ). In addition, double arcsine analysis showed similar results (P = 0 .03 , 95 %CI:0 .02 -0 .04 , Supplementary Figure 1 ).

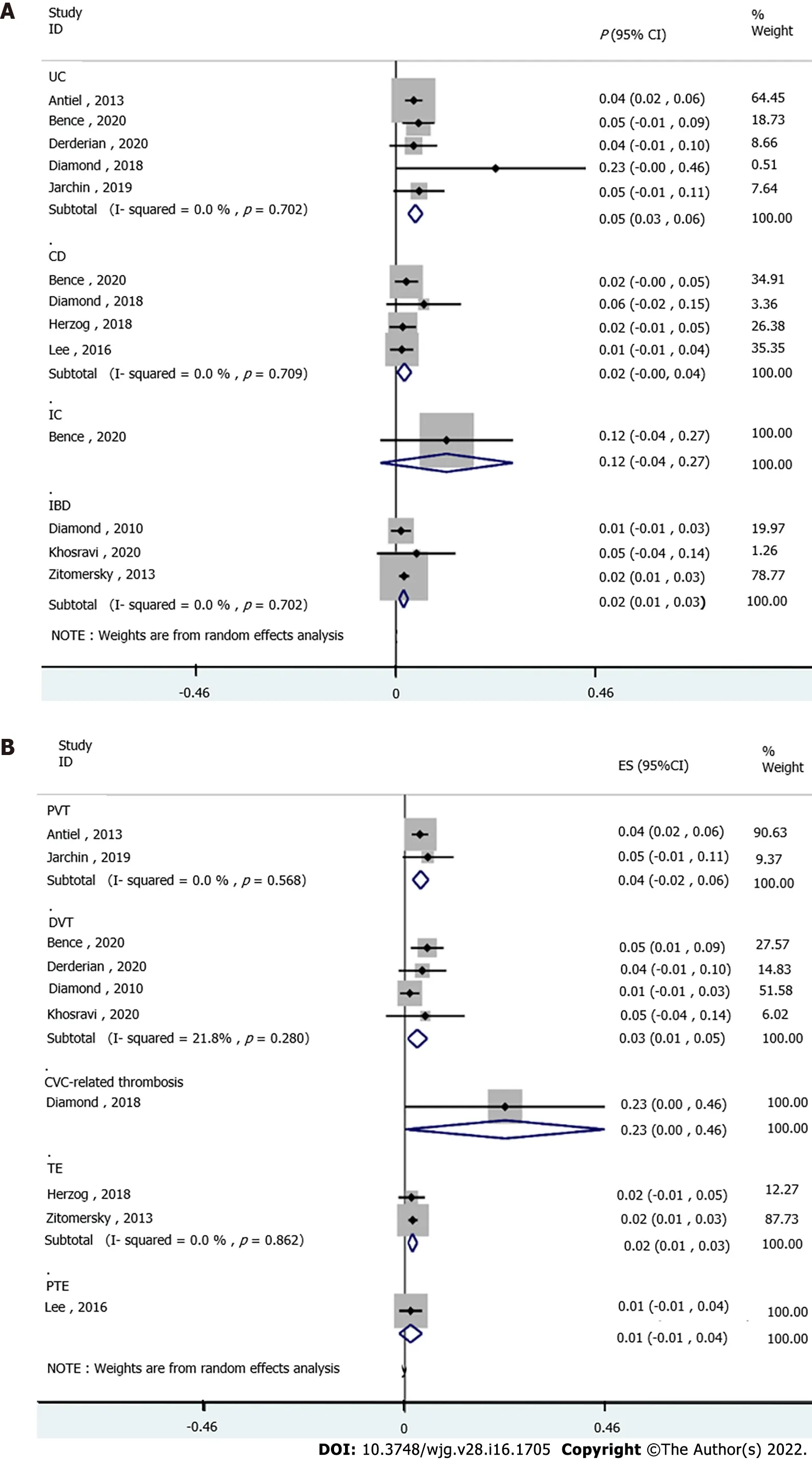

The subgroup analyses stratified by IBD subtype were performed to evaluate the VTE risk in IBD.Five studies analyzed the UC subtype, and the pooled results suggested significantly increased VTE incidence in UC patients (P= 0 .05 , 95 %CI: 0 .03 -0 .06 ). No heterogeneity was detected among the studies(I2= 0 .0 %, pheterogeneity = 0 .571 , Figure 3 A). Pooled analysis of four studies established a correlation between VTE risk and CD (P= 0 .02 , 95 %CI: 0 .00 -0 .04 ), without heterogeneity (I2 = 0 .0 %, pheterogeneity = 0 .709 ,Figure 3 A). The IBD subtype was not defined in three studies, and a high rate of VTE was also detected in these patients (P= 0 .02 , 95 %CI: 0 .01 -0 .03 ), without obvious heterogeneity (I2 = 0 .0 %, pheterogeneity = 0 .702 ,Figure 3 A). Based on one study, the VTE incidence was not increased in IC patients (P = 0 .12 , 95 %CI: -0 .04 to 0 .27 , Figure 3 A).

Stratified by VTE subtype, two studies showed significantly increased PVT incidence in IBD patients (P= 0 .04 , 95 %CI: 0 .02 -0 .06 ; I2 = 0 .0 %, pheterogeneity = 0 .568 , Figure 3 B). The pooled analysis of four studies showed a high risk of DVT in IBD patients (P= 0 .03 , 95 %CI: 0 .01 -0 .05 ) with low heterogeneity (I2 =21 .8 %, pheterogeneity = 0 .280 , Figure 3 B). In addition, one study revealed an increased risk of CVC-related thrombosis in IBD (P= 0 .23 , 95 %CI: 0 .00 -0 .46 , Figure 3 B). Furthermore, two studies showed a significant association between TE risk and IBD (P= 0 .02 , 95 %CI: 0 .01 -0 .03 ), without heterogeneity (I2 = 0 .0 %,pheterogeneity= 0 .862 , Figure 3 B). No association was found between PTE and IBD disease (P = 0 .01 , 95 %CI: -0 .01 to 0 .04 , Figure 3 B) based on one study.

Figure 1 Flowchart of the search process of our study.

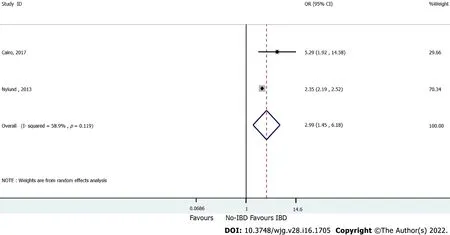

Pooled analysis of two studies comparing IBD and non-IBD patients showed a significant correlation between VTE risk and IBD disease (OR = 2 .99 , 95 %CI: 1 .45 -6 .18 ). Moderate heterogeneity was observed among these studies (I2= 58 .9 %, pheterogeneity = 0 .119 , Figure 4 ).

Publication bias

Publication bias was analyzed using a funnel plot. The asymmetrical distribution suggested significant publication bias (Figure 5 ).

DISCUSSION

The present meta-analysis found that the VTE risk was significantly increased in children and young adults with IBD. A high incidence of VTE was observed in the different subtypes of IBD, including UC,CD, and other undefined IBD diseases. Moreover, multiple VTE signs related to PVT, DVT, TE, and CVC-related thrombosis might be prone to developing during the progression of pediatric and adolescent IBD.

Figure 2 Forest plots of the incidence of venous thromboembolism in inflammatory bowel diseases.

This study suggested that children and young adult IBD patients were susceptible to VTE risk after treatment, despite a low overall incidence. The increased risk of VTE is specific to IBD. Other chronic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, or chronic bowel diseases, such as celiac disease,are not found to be accompanied by a high incidence of VTE[26 ]. The association between VTE risk and IBD has been demonstrated in various IBD patient populations. Currently, there is a lack of systemic reviews on VTE risk in pediatric and adolescent patients. Female pediatric IBD patients were found to be at a high risk of developing VTE[28 ]. The meta-analysis by Kim et al[42 ] focused on pregnant women with IBD. The findings showed a significantly higher incidence of VTE during pregnancy and postpartum in female IBD patients. According to the VTE subtype, the risk of DVT increased significantly in pregnant women, whereas the increase in PE was not significant during pregnancy. In the subgroup analysis based on the location of IBD, patients with UC had significantly higher VTE risk during both pregnancy and the postpartum period, while CD patients exhibited increased VTE incidence only during pregnancy. Therefore, elevated VTE risk was found to be more apparent in UC patients than CD patients. A recent study showed a high postsurgical VTE risk in patients with UC but not in those with CD[43 ]. Similar results were published earlier[44 ,45 ]. However, those studies were performed in the postsurgical setting, which is a state known to be associated with an increased risk of VTE[46 ,47 ]. Similarly, the current study showed a higher risk of VTE in UC compared to CD in children and young adult IBD patients, and consistently suggested that children with UC might be more susceptible to VTE. The exact causes for this higher VTE risk in UC than CD are unknown, but severe UC is associated with anemia and reactive thrombocytosis, which is conducive to VTE[48 ,49 ].

Another meta-analysis by Yuharaet al[50 ] demonstrated that adult patients with IBD (> 20 -years-old)were at increased risk for both DVT and PE. The study also showed that confounding factors, such as smoking and body mass index (BMI), did not affect the correlation between IBD and DVT/PE. A largepopulation database study by Nylundet al[25 ] found that hospitalized children and adolescents with IBD had a high incidence of TE, including DVT and PE. In addition, the study identified older age and abdominal surgery as risk factors for TE in children and young adults with IBD. The Hispanics had a low risk of TE among all children and adolescents. Although tobacco use was a risk factor for TE in adults, it was a protective factor in children with IBD. Interestingly, an increasing trend of TE was observed through the years among children and young adults with IBD, which might be associated with increased hospital admission rates. However, this increasing trend was not clear after multivariable regression analysis. Similarly, the review by Lazzeriniet al[51 ] suggested an increased risk of TE in pediatric IBD patients compared to the general population. Our meta-analysis included several updated publications and showed that the risk of PVT, DVT, TE, and CVC-related thrombosis was increased in IBD child and adolescent patients. Moreover, the underlying mechanism of location-related VTE occurrence and development needs further exploration.

Figure 3 Forest plots. A: Subgroup analysis of the incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) subtype; B: Subgroup analysis of the incidence of VTE subtype in IBD.

Figure 4 Forest plots of the risk of venous thromboembolism in inflammatory bowel diseases and non-inflammatory bowel diseases.

Figure 5 Publication bias; funnel plot of the incidence of venous thromboembolism in inflammatory bowel diseases.

Nevertheless, the present study has several limitations. First, moderate heterogeneity was detected in the overall analysis of the correlation between VTE and IBD. On the other hand, low or no heterogeneity was detected after stratifying the studies by subtypes of VTE and IBD. Patients’ characteristics,diagnosis of VTE, and intervention therapies might contribute to the variations across the studies and the magnitude of association. Second, certain subgroup analyses only involved a small number of studies and patients, and hence, the findings should be interpreted with caution. Third, the included large-size database review study incorporated registry data of medical records with different populations and settings, which might generate a high selection bias. Fourth, VTE was challenging to diagnose, which might have led to the misclassification of VTE.

CONCLUSION

Pediatric and adolescent IBD patients have an increased risk of VTE. UC and CD patients exhibited a high risk of VTE. The risk of VTE subtypes was increased in IBD patients.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

FOOTNOTES

Author contributions:Wang CL, Liang L, Fu JF, Zou CC, Hong F and Wu XM designed the research; Wang CL, Zou CC, Hong F and Wu XM performed the research; Xue JZ and Lu JR contributed new reagents/analytic tools; Wang CL, Liang L and Fu JF analyzed the data; Wang CL, Liang L and Fu JF wrote the paper.

Conflict-of-interest statement:The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

PRISMA 2009 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2009 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2009 Checklist.

Open-Access:This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BYNC 4 .0 ) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is noncommercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4 .0 /

Country/Territory of origin:China

ORCID number:Xin-Yue Zhang 0000 -0001 -9934 -1566 ; Hai-Cheng Dong 0000 -0001 -7830 -2728 ; Wen-Fei Wang 0000 -0001 -7373 -234 X; Yao Zhang 0000 -0003 -2855 -8690 .

S-Editor:Wang LL

L-Editor:Webster JR

P-Editor:Yu HG

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年16期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2022年16期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- LncRNA cancer susceptibility 20 regulates the metastasis of human gastric cancer cells via the miR-143 -5 p/MEMO1 molecular axis

- Guidelines to diagnose and treat peri-levator high-5 anal fistulas: Supralevator, suprasphincteric,extrasphincteric, high outersphincteric, and high intrarectal fistulas

- Association of maternal obesity and gestational diabetes mellitus with overweight/obesity and fatty liver risk in offspring

- Noninvasive imaging of hepatic dysfunction: A state-of-the-art review

- Small nucleolar RNA host gene 3 functions as a novel biomarker in liver cancer and other tumour progression

- Aspartate transferase-to-platelet ratio index-plus: A new simplified model for predicting the risk of mortality among patients with COVID-19