营造健康社区:场所、过程与未来的思考

著:(美)安·福赛斯 译:刘康 刘欣宜 校:陈崇贤

1 健康场所:回顾与展望

如何营造一个健康场所?大多数城市规划设计,从自行车友好城市到绿地空间可达性,都关注建成环境如何影响健康。但是,长期致力于从事该研究领域的人意识到,仅靠建造一个物理空间是无法营造真正的健康场所的;事实上,规划师和设计师在城乡地区还需要解决评估、设计、建造、使用、运营、管控、策划以及更新等一系列问题[1-2](图1~4)。这种综合的工作方式把营造的过程与场所融合,不仅是建造一个包含促进健康作用要素的场所,而且更全面地回应了“应该建造什么”“如何建造”,以及“为谁建造”的问题。在这种方式下,场所不再是一个静态的环境,而是一种随着时间的推移、根据不同的用途和使用者而发展的存在[3]。

图1 公园为人们提供了可以进行体育活动的场所,而其绿色空间可以提升人们的心理健康(中国北京)Parks provide settings where people can choose to undertake physical activity and as green areas can enhance mental well-being (Beijing, China)

图2 健康场所提供了各种实现健康生活的基础,但有时也会带来安全与污染问题(中国北海)Healthy places provide options for gaining access to the resources needed for a healthy life but some options can also can pose problems in terms of safety and pollution(Beihai, China)

图3 健康场所既关于如何使用空间,也关于如何设计空间。图中,人们在人行道上跳舞(墨西哥瓦哈卡)Healthy places are as much about how spaces are used as how they are designed.In this image people dance in a pedestrianized street (Oaxaca, Mexico)

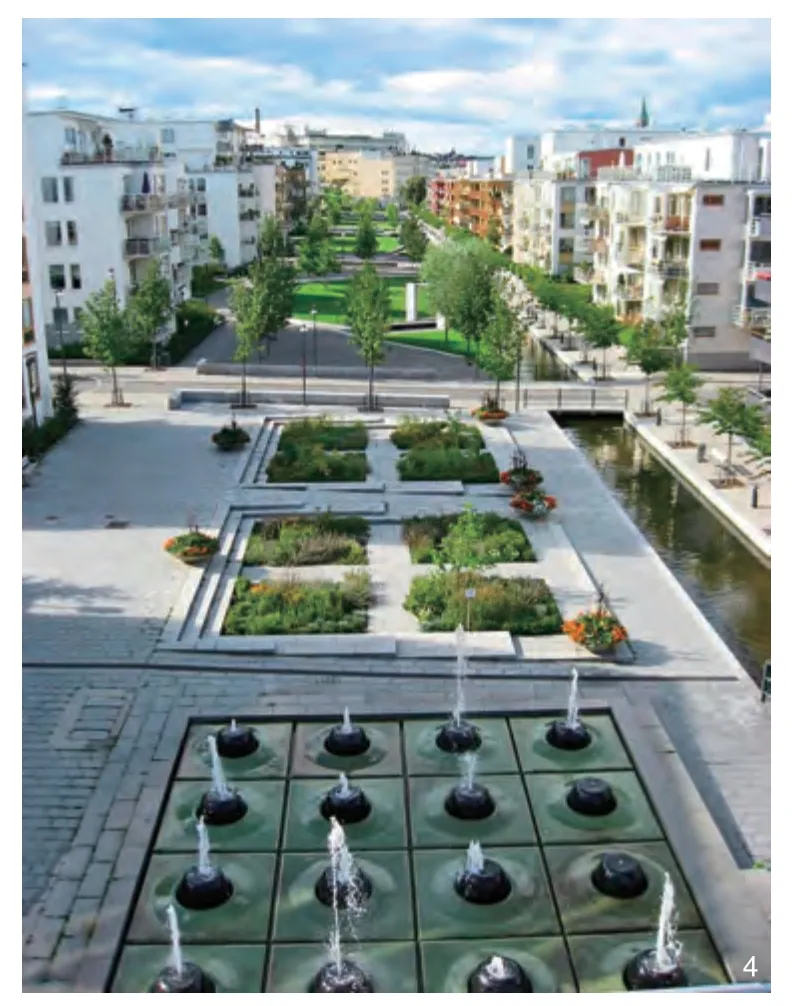

图4 营造健康场所的相关策略,与实现可持续发展和提高生活质量目标所需要的策略类似。斯德哥尔摩的哈马碧滨水新城是一个城市更新项目,旨在减少其生态足迹,但同时它有许多促进健康的要素,如网络化的道路系统以及方便到达的蓝绿空间(瑞士哈马碧滨水新城)Many strategies for creating healthy places are similar to those achieving other aims such as sustainability or quality of life.Hammarby Sjöstad in Stokholm is an urban redevelopment designed to minimize its ecological footprint but it has many health promoting features such as networked path systems and access to water and green space (Hammarby Sjöstad, Sweden)

在2017年出版的《营造健康社区:基于循证的规划设计策略》(Creating Healthy Neighborhoods: Evidence-Based Planning and Design Strategies,简称《营造健康社区》)中,探讨了关注场所的物理环境的同时也应重视营造更健康场所的过程性。该书是由我与埃米莉·萨洛蒙(Emily Salomon)、劳拉·斯米德(Laura Smead)二位合著的,综合了各个领域的研究,是一本城市规划与设计领域的实践手册[4]。该书主要针对中高收入国家的居住区环境,也受到了当下为老龄化社会创造更健康环境的挑战的启发,旨在弥补研究与实践之间的鸿沟。书中提出8项普遍性原则与20项针对性建议,并列举了83项具体措施。其中5项原则关注环境:有利健康的空间布局、可达性方式的选择、支持积极的社会关系、防止危害与污染物的措施、满足最弱势群体基本需求的规划(包括住房条件、食物来源与交通等)。另外3项原则考虑了营造场所的过程及居住与使用的人群,包括在特定情景下评估健康的重要性:关键的健康问题与相关利益者、物理干预与其他健康促进措施之间的权衡、持续动态化的措施。

在《营造健康社区》出版几年后,经历了新冠肺炎疫情,我又重新回顾了这项工作,以此思考基于循证方法营造健康场所的潜在可能性与局限性。这篇文章是实践反思的一个例子,审视先前的工作以理解循证实践是如何产生的,是否经得起自我检验,以及它对未来营造更健康的社区意味着什么。完善的循证实践可以产生诸多效益,但由于它需要建立长时间的多方协作,所以难以实现。

2 如何产生:《营造健康社区》的形成过程

《营造健康社区》不是一蹴而就的,它整合了几十年来有关健康与场所的研究工作,试图让它变得更具实用性。其中包括先前的研究简报与健康影响评估工具的开发,开展健康和创新社区的原创性研究,以及对循证实践优势与局限的探究。我与合著者曾作为规划师的实践经验也为这项工作提供了重要的基础。

2.1 证据权衡的整合

该书直接借鉴了已有的健康研究结果,基于实用性视角进行了2次整合梳理。在这些研究报道中筛选了许多独立研究与综述的文章,确定了证据权衡支持的关键发现以及有待探究的问题,同时,还考虑了与弱势群体相关的内容,以便为设计实践提供参考[5]。受到其他领域类似项目的启发,我们做了大量整合多项研究的工作。这项工作意味着规划师与设计师可以利用一个研究领域中所有证据发现综合的结果,而不是依赖于一两个高度公开但无法反映更大范围结果发现的研究。该整合工作的第一阶段成果——健康设计(design for health, DFH)规划信息表,是来自我在2005年左右在明尼苏达大学负责的第一个项目;而第二阶段成果——“怡城”(Health and Places Initiative, HAPI)项目研究简报,是2015年左右在哈佛大学负责项目的一部分成果,该项目主要关注中国地区人口老龄化问题[5]。

尽管每个研究领域探究的具体问题有所不同,但我们的整合研究工作基本聚焦在几个方面:即使人们暴露在有噪声或低空气质量等有害因素中,也能免受其害的环境;让人们能够获得社区服务或社会互动等健康生活基本需求的环境;支持健康饮食和体力活动等健康行为的环境。由于研究结果参差不齐,一些问题的相关研究较为丰富,而另一些则相对缺乏,这增加了整合研究结果的复杂性。但最终这些对多项研究结果的总结构成了《营造健康社区》的主体内容。

人们也许会问既然已有许多作者在尽心撰写文献综述,为什么还需要这些总结?尽管类似的综述十分有必要,但它们涉及的内容范围较为局限。在实践中,设计师需要站在更高的角度以应对更广泛的问题,同时还需要考虑哪些是真正适合规划和设计的干预措施。

《营造健康社区》中提及的策略也体现了我们在相同的项目中进行2次健康影响评估工作的经验总结,相关工作包括了制定清单、举办研讨会以及基于地理信息系统(geographic information system, GIS)的 大尺度场地处理[6-8]。这些工作强调了找出健康相关问题的过程,让当地居民参与并理解具体问题,评估方案、策划和现有场所的健康效益。虽然这些工作内容的设定是为了评估设计与开发提案,但也能用于评估现有的场所,这种回顾性健康影响评估(health impact assessment, HIA)的形式,也可称为健康评估(health assessment)。

在开发这些评估工具的10多年时间里,我担心这种措施清单的模式在某种程度上过度简化了研究内容。然而,从业者十分感谢能通过一种简单的方法评估他们所做的工作,尤其是针对城市规划和设计领域。在历代工具中,我更倾向于快速健康影响评估(the rapid HIA)。通过精心设计的研讨会形式,让来自不同领域及不同知识背景的参与者都可以对提案和现有的证据(如研究、项目调查及地方知识等)提出反馈。《营造健康社区》既借鉴了以清单为导向的评估要素,也参考了研讨会形式背后的想法,即把不同的群体和不同形式的知识聚集在一起。

2.2 关于健康场所和社区规划的研究

我开始创建这类研究整合和健康评估工具的部分原因是希望健康与场所的研究更容易在实践中应用,但这是一项棘手的工作。在健康研究领域,规模庞大的团队通常将一个问题拆分为许多相互联系且小而细的问题进行研究。这就意味着每个研究人员都只了解一个相对细小的问题,但在实践中,各类问题和不同的环境因素都有可能是重要的。此外,需要筛选大量研究来找出细微但重要的差异,关于“密度”(density)的讨论就是其中一个例子。密度差异会带来不同的效应,取决于具体的健康问题、场地及人群,这在关于紧凑型和分散型城市的争论中有所体现[9]。同样地,混合用地并不是对所有人群与健康问题都有益,一个高密度混合使用区,对身体健康的成年人来说有助于他们进行体力活动与获取相关资源,但对于患有哮喘的老年人却是具有挑战性的。

关于体力活动和饮食环境的研究,让我站在了专业的角度看待健康研究的动机和实践。过往的工作使我明白外部环境、体力活动以及健康饮食之间的联系比最初预想的要复杂,这种复杂联系的呈现通常可见于研究文章中,而非媒体报道中。我意识到当证据的权衡起到关键作用的时候,去推广一项研究的内容在某些方面会有很大压力。

我的第二个研究领域是包括新城镇在内的创新型社区规划,这也是该书框架的核心。我对健康的兴趣源自可持续性设计,为此写了一系列有关全球各地社区规划调查的书和文章[10-12],这些基于案例研究的项目让我深刻认识到采取创新方法来营造城市空间的必要性[13]。我对如何营造更好的场所以及创造什么样的空间的兴趣,促成了《营造健康社区》这本书。

2.3 循证实践

最后探讨的是循证实践(evidence-based practice, EBP)最大的问题——即它如何以及是否能真正改善规划和设计的结果[14],这是一个长期存在的问题。目前循证实践的实施也面临诸多挑战,包括:从业者通常依靠自己所受的设计训练和实践经验做出决定,而不依赖于研究性知识,因而循证实践对他们来说没有吸引力;一个具有稳定扎实的研究领域可能与规划设计关联较少,这使得循证实践缺少实用性;针对一类地区或一个时间段的研究结果难以具有普适性;另外,一些研究由于缺少研究结果而无法发表,从而导致研究的不均衡[15]等。

但是,我在《营造健康社区》中阐述了我的观点,即循证实践是具有可操作性的,该书的确解决了它的局限性。该书以过程为导向,让使用者能够根据不同的情况来运用健康知识。同时,我们也阐明了现有证据的优势所在,以免夸大其结论确定性的程度。例如,书中提出的83项措施根据证据确定性程度分类,即直接由研究证据获得、大体上由此类证据获得,以及可能有助于改善健康且至少不会损害健康的实践。我们还尝试解决在缺乏证据的情况下如何做出决策的问题,并区分一些普遍的健康结果和行为。例如,对污染物的身体反应,个人、社会或文化方面的健康问题的比较[4]4-7。虽然物理场所对健康很重要,但并不是唯一决定因素,而这也是该书的关键主题。

另一个问题与创造力和专业判断力相关。虽然一些从业者认为在研究现状和人与场地的各种问题时,循证实践会帮助他们更确切地知道怎么做规划,而另一些人则认为这会削弱他们的创造力。该书和来自同一项目的配套书,尤其是戴维·玛(David Mah)和阿塞西欧·维罗利亚(Ascencio Villoria)[16]的《生活方式:健康生活与场所》(Life-Styled: Health and Places),试图改变大家对循证实践抑制创造力的看法,提出健康证据概念化可以激发想象力的观点[4,12]。在我较早的一本书里,我将公园设计中社会与生态问题之间的权衡,看作是不同类型的设计灵感来源,最终的规划设计取决于优先考虑什么。尽管项目中健康目标不同,但可以产生相同的效益[17]。

3 后疫情时代

营造一个健康的场所到底需要什么?《营造健康社区》写于疫情时代之前,虽然明确地指出洁净的空气和水的重要性,但更强调了建成环境如何影响像肥胖、癌症这类非传染性和慢性疾病。总的来说,该书比我想象中更能经受住时间的考验,这在一定程度上得益于这些策略涉及的是较为开放的社区,而不是封闭的工作场所或室内空间。

在后疫情时代,人们对社区空间的使用发生了许多微妙的变化[18]。在文献研究中,户外空间一直是进行体力活动、社会互动、精神恢复等活动的重要场地,但由于疫情时代下室内更易感染,户外空间变得尤为重要。远程办公的兴起让居住区成为日常生活的主要场所,这恰恰强调了该书中对居住和混合用途社区的关注。这场疫情给予我们的教训是有所准备十分必要,就像早先抗击过重症急性呼吸综合征(SARS)的国家在面对新冠肺炎疫情时会先取得初步进展[18]。尽管近年来这种观点流传十分广泛,但这不是新的见解。

该书一个更细分的主题是人口老龄化的规划设计,这也是一个全球都关注的问题。在人口增长和气候变化等外部因素共同作用下,老龄化问题愈发突出[19-20],新冠肺炎疫情也让我们清晰地看到这类人群的脆弱性。当然,社区并不是老年人唯一关键的环境因素——家庭情况、住宅条件及文化要素也扮演重要的角色[21]。我从新冠肺炎疫情中认识到,将老年人视为更广泛社区潜在资源的必要性,创造能让他们充满活力的环境将有益于整个社会,这也是该书的一个细小但重要的主题。

在后疫情时代,最后一个需要明确的是创造健康环境过程中合作和治理的问题。正如我在其他地方所提到的,新冠肺炎疫情刺激了公众与政府采取紧急措施,如隔离政策、保障必要的医务和后勤工作人员,以便应对疫情及产生的后果[18]。我在新冠肺炎疫情暴发前完成的一篇关于不同健康场所营造的文章中,探讨了大众和专业讨论中常见的几种形式。这其中包括最基本的途径,即与其他机构,如与世界卫生组织的健康城市项目(WHO Healthy Cities program)[22]合作进行健康建成环境研究,涉及的议题包含老幼友好社区规划以及在健康城市中应用新技术等[2]。即使不是每项战略和部署都需要跨机构和区域的合作,但它们仍是创造健康城市基本理念的核心,也是《营造健康社区》的未来愿景。

在疫情期间,即使将健康问题摆在重要的位置,建立这样的合作关系显然也是困难的,因为社会关系会遭遇危机,合作有可能中断,人们也会对政府的职能感到失望。此外,需要公众参与的行动本就具有挑战性,更不用说在新冠肺炎疫情这一严重的形势下。而规划师和设计师讨论典型但细微的健康影响,让人们更有可能忽略或否定干预措施,质疑其必要性,这阻碍了创造真正的健康场所所需的合作。即使合作十分困难,我们在《营造健康社区》一书中仍对合作持乐观的态度。该书的大多数策略和行动除与健康相关之外,还具有多种益处,以便它更容易被接受。总之,一个关键的要点是,营造更健康的场所需要同时应用多种不同的策略,这需要紧密的合作,但新冠肺炎疫情的经历让合作变得非常困难。

图片来源:

文中图片均由安·福赛斯提供。

(编辑/刘玉霞)

著者简介:

(美)安·福赛斯/女/博士/哈佛大学设计研究生院城市规划专业露丝和弗兰克·斯坦顿讲席教授、城市规划硕士项目主任/研究方向为社会层面的实体规划

译者简介:

刘康/女/华南农业大学林学与风景园林学院在读硕士研究生/研究方向为风景园林规划设计与理论

刘欣宜/女/华南农业大学林学与风景园林学院在读硕士研究生/研究方向为风景园林规划设计与理论

校者简介:

陈崇贤/男/博士/华南农业大学林学与风景园林学院副教授/本刊特约编辑/研究方向为风景园林规划设计与理论

FORSYTH A.Creating Healthy Neighborhoods: Reflecting on Places, Processes, and Prospects[J].Landscape Architecture, 2023, 30(1): 12-19.DOI: 10.12409/j.fjyl.202208050470.

Creating Healthy Neighborhoods: Reflecting on Places, Processes, and Prospects

Author:(USA) Ann Forsyth Translators: LIU Kang, LIU Xinyi Proofreader: CHEN Chongxian

Abstract:[Objective]What does it really take to create a healthy place? What are the potentials and limits of evidence-based practice?[Methods]Reflecting on the experience of many years of writing about healthy places, I consider the potential for evidence-based practice.[Results]Neighborhoods can protect from harmful exposures, help people connect to the resources they need to live a healthy life, and support health promoting behaviors.[Conclusion]Creating healthy places involves more than developing environments with features thought to be health promoting, however, but rather also engaging the process of making, maintaining, and using such places.Most challenging for this kind of comprehensive approach is the need to create ongoing collaborations.

Keywords: healthy city; healthy neighborhood; healthy place; built environment;evidence-based practice

1 Healthy Places in Retrospect and Prospect

What does it really take to create a healthy place? Many in urban planning have focused on how the built environment can affect health — from planning for bicycle safety to green space access.But even those who have invested great time in this research area also understand that to make healthy places it is not enough to just build a physical space;rather planners and designers need to address the processes of assessing, designing, constructing,using, managing, regulating, programming,and revitalizing urban and rural areas as well[1-2](Fig.1-4).Such comprehensive approaches,combining places with processes, do more than assume that building a place with features thought to be health promoting will improve health.Rather,they more comprehensively address what should be built, how, and for whom.They not only look at a place as a static environment but as something that evolves over time with different uses and users[3].

图1 Parks provide settings where people can choose to undertake physical activity and as green areas can enhance mental well-being (Beijing, China)

In 2017, I published a book that while focused on physical places, also addressed the process of making healthier places.Creating Healthy Neighborhoods: Evidence-Based Planning and Design Strategies, co-authored with Emily Salomon and Laura Smead, synthesized research from a variety of fields to create a handbook for urban planning and design practice[4].Targeted at residential areas in middle and high-income countries, and inspired by the challenges of creating healthier environments for an aging population,it aimed to bridge the research-practice gap.Built around eight general principles and 20 specific propositionsit also outlined 83 actions.Five of the major principles focused on the environment —health promoting layouts; access options; supports for positive social connections; protections from hazards and pollutants; and planning for basic needs for the most vulnerable such as housing options,food access, and mobility.Three considered the process of making places and the people inhabiting and using them.These included assessing health’s importance in the specific situation — important health issues and constituencies; balancing physical interventions and other health-promoting activities;and implementing strategies over time.

Several years after completing Creating Healthy Neighborhoods, and in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, I look back at that work,using it as a lens for considering the potential and limits of evidence-based approaches to making better places.This article is an example of reflective practice, examining prior work to understand how it came about, how it stands up to my own scrutiny in hindsight, and what this might mean for creating healthier environments in the future.Robust evidence-based practice has many benefits but is hard to pull off, not least because it requires collaboration over time.

图2 Healthy places provide options for gaining access to the resources needed for a healthy life but some options can also can pose problems in terms of safety and pollution(Beihai, China)

2 How It Came About: The History of Creating Healthy Neighborhoods

Creating Healthy Neighborhoodswas not a one-off manual but rather drew on some decades of work trying to make research on health and places more accessible.This included prior work developing research summaries and health impact assessments, conducting original research on health and on innovative communities, and trying to understand the strengths and limitations of evidence-based practice.I and my co-authors had also practiced as planners and those experiences provided an important context for the work.

2.1 Summarizing the Balance of Evidence

Most immediately the book drew on two iterations of developing short practical syntheses of health research.These briefs sifted through many individual studies and review articles, identified key findings supported by the balance of evidence as well as what was up in the air, considered the topic in relation to vulnerable groups, and developed insights for practice[5].Inspired by similar projects in other fields, we did the hard work of synthesizing multiple studies.This would mean that planners and designers could use the results of a whole body of evidence on a topic and would be less prone to relying on one or two highly publicized studies that might not reflect the larger field.The first generation of these summaries,Design for Health (DFH) Planning Information Sheets, came from a project I co-directed in the mid-2000s at the University of Minnesota.The second generation, the Health and Places Initiative(HAPI) Research Briefs, were developed as part of a project in the mid-2010s at Harvard University in a project with an emphasis on the aging population and a geographical interest in China[5].

图3 Healthy places are as much about how spaces are used as how they are designed.In this image people dance in a pedestrianized street (Oaxaca, Mexico)

While the exact topics explored in each series differed, the summaries generally focused on areas where the environment could expose people to often harmful elements such as noise or poor air quality but alsoprotect them from these effects,connect them to the resources they need to lead a healthy life including community services or social interactions, and support health related behaviors such as eating well and being physically active.Research is unevenly available with many studies on some topics and few on others posing complexities for synthesizing the results.These summaries of multiple studies formed the backbone of theCreating Healthy Neighborhoodsguidebook.

It would be reasonable to ask why these summaries were needed when there are many authors industriously churning out literature review articles? Such reviews are of course tremendously useful but also often quite narrow in scope.For practice one needs to address a wider range of topics at a high level as well as consider which ones are really amenable to planning and design interventions; many are not.

The strategies inCreating Healthy Neighborhoodsalso reflected the experience of developing two iterations of health impact assessments — checklists, workshops, and larger GIS-based processes — created in those same projects[6-8].These emphasized the ongoing process of identifying where health issues may be relevant;engaging local people in to understand specific concerns; and evaluating plans, programs, and existing places in terms of their health outcomes.Developed to assess plans and proposals, they were also potentially used to assess existing places, a form of retrospective health impact assessment (HIA)perhaps better termed as a health assessment.

Over the decade of developing these assessment tools I was hesitant about them, worried the checklist format of some oversimplified the research.However, practitioners expressed gratitude to have an easy way to assess what they were doing,and one tailored to urban planning and design.In each generation the tool I liked the best was the rapid HIA.This was an elaborate workshop format where participants representing different constituencies and sources of knowledge would reflect both on a proposal and existing evidence about it including evidence from research, project investigations, and local knowledge.Creating Healthy Placesadapted elements of both the more checklistoriented assessments and the big idea behind the workshop format which was to bring together various constituencies and forms of knowledge.

2.2 Research on Healthy Places and Planned Communities

Part of the reason I had started along the path of creating such research summaries and health assessments was a desire in the practice world for health and place research to be more easily applied to practice.This is a tricky endeavor.In the health research field large teams often look at small and narrowly defined problems with many studies building on one another.That means any single researcher knows a lot about a relatively narrow topic while for practice many topics and a wide range of contextual factors are likely to be important.There may also be a great many studies to sift through with subtle but important differences.The density debate is one example of this where different densities seem to have differing benefits and problems depending on the healthrelated issue, location, and population group,exemplified by competing critiques of congestion and sprawl[9].Similarly mixed land uses can be beneficial for some populations and some health issues and not for others.A high-density mixeduse area might be quite positive in terms physical activity and access to resources for an able-bodied adult but have challenges for a frail older person with asthma.

图4 Many strategies for creating healthy places are similar to those achieving other aims such as sustainability or quality of life.Hammarby Sjöstad in Stokholm is an urban redevelopment designed to minimize its ecological footprint but it has many health promoting features such as networked path systems and access to water and green space (Hammarby Sjöstad, Sweden)

My own research on physical activity and food environments gave me an insider’s view of the motivations and practices of conducting health research.From my own work I knew the connections between the environment, total physical activity, and healthy eating are more complicated than many at first thought.Such connections were typically reflected in the research articles though not the press releases about them.I also understood that there was great pressure in some quarters to promote the message of an individual piece of research when it was obvious that the balance of evidence was what mattered.

A second area of my own research, on innovative planned communities including new towns, was also key in framing the book.I came to an interest in health from an initial interest in how to design for sustainability writing a series of books, articles, and chapters investigating planned communities on multiple continents[10-12].These case-study-based projects on multiple continents gave me a strong appreciation of what it takes to undertake innovative approaches to creating urban places[13].This interest in the how to make better places as well as whatto make informedCreating Healthy Neighborhoods.

2.3 Evidence-Based Practice

Finally, was the larger question of evidencebased practice (EBP) — how it might be possible and whether it actually improves planning and design outcomes[14].This is a longstanding question.Practitioners typically make decisions using their own training and experience rather than research knowledge, making EBP unattractive to some.An area with robust research may have few links to planning and design, making it less useful.Results from one type of place or one time period can be hard to apply to another.Studies that do not find effects are less likely to be published, biasing the research record[15].All this makes EBP quite challenging.

Obviously by writing the book I have declared my opinion that evidence-based practice is possible.However, the book does address its limitations.the book’s process orientation allows users to tailor health knowledge to multiple situations.We also clarified the strength of the existing evidence so as not to overstate its level of certainty.For example,the 83 actions in the book are classified in terms of the level of certainty — directly informed by research evidence, generally informed by such evidence, and good practices that might help improve health and at least would not harm it.We also attempted to address how to make decisions in the absence of evidence and to distinguish between somewhat universal health outcomes and behaviors e.g., bodily reactions to pollutants, compared with health issues that were more individual, social, or cultural[4]4-7.While physical places matter for health they are not the only determinant of health, and this is also a key theme in the book.

Another issue is that of creativity and professional judgment.While some practitioners want more certainty about what to do than is possible given the state of research and the diversity of people and places, others chafe at what they perceive as a diminution of creativity in EBP.The book and its companion volumes from the same project, particularly David Mah and Ascencio Villoria’s[16]Life-Styled: Health and Places, tried to move beyond the perceptions evidencebased practice as suppressing creativity.Rather they conceptualize health evidence as a potential spark for the imagination[4,12].In an earlier book I had addressed the tradeoffs between social and ecological concerns in park designs as inspirations for different kinds of designs depending on what is prioritized; different health objectives can have something of the same role[17].

3 The Post-COVID Picture

What does it really take to create a healthy place? Written in the pre-COVID world the book emphasized how the built environment affected non-contagious and chronic diseases like obesity and cancer, although it did point out that clean air and water were important.On balance, this has stood the test of time better than I thought it would.This is in part helped by the situation that the strategies deal with neighborhoods, rather than workplaces or home interiors.

Post-COVID, many of the changes in neighborhood spaces use have been subtle[18].Outdoor spaces became important given the potential for indoor contagion; but they had always been important in the literature, providing space for physical activity, social interaction, mental restoration, and the like.The rise of remote work made residential areas key sites for daily life, but this just reinforced the message of the manual that focused on residential and mixed-use neighborhoods.A lesson of the pandemic was preparedness matters, hence the countries that had earlier faced SARS had initial success in combatting COVID-19[18].Again, however, this was not such a new insight though very powerfully conveyed in recent years.

A more subtle theme of the book was the issue of planning and design for an aging population, a topic of concern globally as the difficulties of aging are combined with demographic shifts and external forces like climate change[19-20].COVID-19 has demonstrated the vulnerability of this population.Of course,neighborhoods are not the only important environment for older people — the home and building are also key as is the wider culture[21].A lesson I eventually took from COVID-19 was the importance of seeing older people as a potential resource for the wider community.Creating environments that allow them to thrive and flourish is important for the whole society and is a theme of the book, if a subtle one.

A final important topic made more clear after COVID is the issue of cooperation and governance to create a healthier environment,something we indicated would be needed.As I have noted elsewhere COVID-19 spurred very notable public and governmental initiatives to address the pandemic and the fallout from the response — from banning evictions to redefining essential workers[18].In an article on types of healthy places, completed pre-COVID, I looked at different types common in popular and professional debates.These included the most basic approach combining healthy built environments and collaborative approaches like the WHO Healthy Cities program[22], along with ageand child-friendly versions, and those using new technologies[2].Collaboration across institutions and constituencies is at the core of the basic idea of the healthy cities and was also key in the larger vision ofCreating Healthy Neighborhoods, if not needed for every single strategy or action.

Even at times when health is front and center, as in the COVID-19 pandemic, it is obvious that collaboration is difficult.Social ties can fray,cooperation might break down, and populations can become disenchanted with government mandates.While some of the actions required of the public were quite challenging, so was the seriousness of the situation under COVID-19.The typical kinds of subtle health effects planners and designers are dealing with make it even more likely that people will ignore or dismiss interventions,questioning their necessity, and undermining the kind of cooperation needed to create truly healthy places.The bookCreating Healthy Neighborhoodsstruck an optimistic tone about cooperation,even as we knew it would be difficult.Most of the strategies and actions in the guidebook have multiple benefits beyond those related to health making them more likely to be adopted.However,a key idea is that healthier places use many different strategies at once requiring very substantial coordination.The COVID-19 experience has shown how difficult this can be.

(Editor / LIU Yuxia)

Author:

(USA) Ann Forsyth, Ph.D., is Ruth and Frank Stanton Professor of Urban Planning and Director of the Master in Urban Planning Program, Graduate School of Design,Harvard University.Her research focuses on social aspects of physical planning

Translators:

LIU Kang is a master student in the School of Forestry and Landscape Architecture, South China Agricultural University.Her research focuses on landscape planning and design,and theory of landscape architecture.

LIU Xinyi is a master student in the School of Forestry and Landscape Architecture, South China Agricultural University.Her research focuses on landscape planning and design,and theory of landscape architecture.

Proofreader:

CHEN Chongxian, Ph.D., is an associate professor in the School of Forestry and Landscape Architecture, South China Agricultural University, and a contributing editor of this journal.His research focuses on landscape planning and design, and theory of landscape architecture.