The implementation and impacts of national standards forcomprehensive care in acute care hospitals: An integrative review

Beiei Xiong ,Christine Stirling ,Melinda Martin-Khan

a Centre for Health Services Research, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia

b School of Nursing, University of Tasmania, Hobart, Australia

c College of Medicine and Health, University of Exeter, Exeter, United Kingdom

d School of Nursing, University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, Canada

Keywords:Acute care Coordinated care Health policy Implementation science Multidisciplinary care Patient-centred care Standard of care

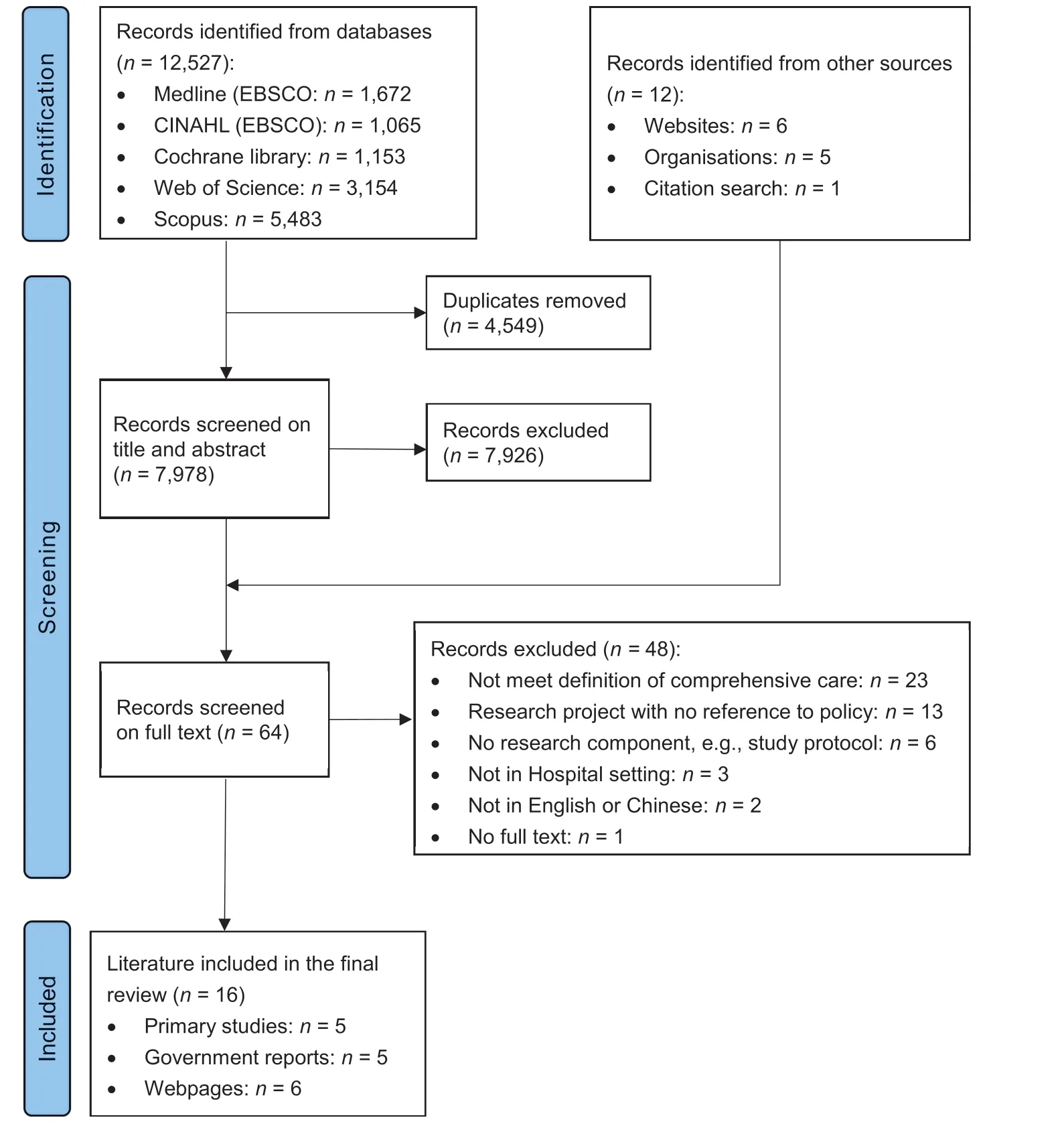

ABSTRACT Objectives: To synthesise current evidence addressing implementation approaches,challenges and facilitators,and impacts of national standards for comprehensive care in acute care hospitals.Methods: Using Whittemore &Knafl’s five-step method,a systematic search was conducted across five databases,including Medline(EBSCO),CINAHL(EBSCO),Cochrane Library,Web of Science,and Scopus,to identify primary studies and reviews.In addition,grey literature(i.e.,government reports and webpages)was also searched via Google and international government/organisation websites.All searches were limited to January 1,2000 to January 31,2023.Articles relevant to the implementation or impacts of national standards for comprehensive care in acute care hospitals were included.Included articles underwent a Joanna Briggs Institute quality review,followed by qualitative content analysis of the extracted data adhering to PRISMA reporting guidelines.Results: A total of 16 articles were included in the review(5 primary studies,5 government reports,and 6 government webpages).Three countries (Australia,Norway,and the United Kingdom [UK]) were identified as having a national standard for comprehensive care.The Australian standard contains a unique component of minimising patient harm.Norway does not have a defined implementation framework for the standard,whereas Australia and the UK do.Limited research suggests that challenges in implementing a national standard for comprehensive care in acute care hospitals include difficulties in implementing governance processes,end-of-life care actions,minimising harms actions,and developing comprehensive care plans with multidisciplinary teams,the absence of standardised care plans and patient-centred goals in documentation,and excessive paperwork.Implementation facilitators include a new care plan template using the Identify,Situation,Background,Assessment and Recommendation framework for handover,promoting efficient documentation,clinical decision-making and direct patient care,and proactivity among patients and care professionals with collaboration skills.Limited research suggests introducing the Australian standard demonstrated some positive effects on patient outcomes.Conclusion: The components and implementation approaches of the national standards for comprehensive care in Australia,Norway and the UK were slightly different.The scarcity of studies found during the review highlights the need for further research to evaluate the implementation challenges and facilitators,and impacts of national standards for comprehensive care in acute care hospitals.

What is known?

· Comprehensive care is becoming a widely acknowledged standard for modern healthcare not just because it provides highquality care but also because it is cost-effective for care providers and patients and their families.

What is new?

· This paper provides a unique overview of current evidence of addressing policy,implementation,and impacts of national standards for comprehensive care in acute care hospitals globally.

· Some differences existed in the components and implementation of Australian,Norwegian,and British national standards for comprehensive care in acute care hospitals.

· The findings of this study indicate a gap in research regarding national standards for comprehensive care in acute care hospitals,which highlights the time-sensitive need for more policybased research following the recent introduction of the new standards in Australia and the United Kingdom.

1.Introduction

Comprehensive care is becoming a widely acknowledged standard for modern healthcare,as the traditional disease-specific approach to care delivery is not sufficient to meet the complex needs of patients [1].The traditional approach often results in reported gaps in safety and quality which can lead to inadequate care for patients under specific conditions or to undesired outcomes within particular populations[2].Many patients require a range of care services from multiple healthcare providers across several settings,but lack of care coordination may result in inefficient,inadequate,or fragmented care,which may cause unnecessary hospitalisation,increased length of stay,and/or adverse events[3,4].As a result,modern healthcare is gradually shifting to a more comprehensive or integrated approach to care delivery.A rapid literature review identifying 16 articles on the effectiveness of comprehensive care indicated that comprehensive care has the potential to improve health service delivery which impacts both patient-centred care and clinical outcomes in acute care hospitals[5].Additionally,comprehensive care has been shown to be costeffective for both care providers and patients [1,6].

According to the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC),comprehensive care is defined as the “coordinated delivery of the total health care required or requested by a patient”(p.44)[7].This definition includes three components:a.coordinated delivery of health care;b.multidisciplinary care plan and delivery;and c.shared decision-making with patients,carers and families.“Comprehensive care” as a concept has been established in several countries,where many different terms are being applied to the same concept such as “patient-centred care”,“multidisciplinary care”,“coordinated care”,and “integrated care”[1,8].However,in reality,those terms have slightly different meanings.To better represent the concept of comprehensive care,we developed a concept map of comprehensive care (Fig.1).

Fig.1.Comprehensive care concept map.

In Australia,the ACSQHC released the Comprehensive Care Standard as part of the National Safety and Quality Health Service(NSQHS) Standards to ensure that patients receive comprehensive health care that meets their individual needs[4].The first edition of the standards was released in 2011,followed by a series of additional standards.One of the latest,the Comprehensive Care Standard was released in November 2017 and came into effect in January 2019.Health service organisations have to meet all of the NSQHS Standards to be awarded accreditation.The delivery of comprehensive care relies on effective communication and teamwork among members of the healthcare team and patients,carers and families partnering to identify,assess and address patients’clinical risks,and determine their preferences for care[7].

Regardless of the magnitude of money invested every year in health care,the quality of health services may still be poor [9].Findings from previous studies indicate that healthcare organisations’efforts to implement changes often fail[10,11].Hence,there is a need to assess not only summative endpoint health outcomes,but also to conduct formative evaluations to examine implementation strategies and challenges in a specific context to optimise the benefits of new care standards,prolong its sustainability,and promote the dissemination of findings into other contexts[12].The objective of this literature review is to synthesise the available research evidence on implementation approaches,challenges and facilitators,and impacts of national standards for comprehensive care in acute care hospitals.This review was initiated by an awareness of the Australian Comprehensive Care Standard.However,we aim to identify and analyse national standards or guidelines for comprehensive care in acute care hospitals globally.By doing so,we aim to contribute to a better understanding of the implementation and impacts of national standards for comprehensive care in acute care hospitals internationally.

2.Method

This study used an “integrative review” approach and adhered to the PRISMA guidelines for reporting on the research methodology and findings.An “integrative review” is the broadest type of research review allowing for combining data from studies conducted using diverse methodologies and can provide a much more holistic view of the prevalence of research on a topic compared to a systematic review limited to a single preferred study design[13,14].Whittemore and Knafl’s (2005) framework for integrative review was followed,consisting of five stages: problem identification,literature searches,data evaluation,data analysis,and presentation[14].

2.1.Problem identification

The problem is identified: What are the implementation approaches,challenges and facilitators,and impacts of national standards for comprehensive care in acute care hospitals?

2.2.Literature search

A search of computerised databases (Medline [EBSCO],CINAHL[EBSCO],Cochrane Library,Web of Science,and Scopus)was carried out using key concepts (comprehensive care standard,hospital/acute care,implementation,and impact/outcome).Medline(EBSCO),CINAHL (EBSCO),and Cochrane Library were searched using subject headings for all key concepts with supplementary keywords for concept 1 (comprehensive care standard) and concept 2 (hospital).Scopus and Web of Science were searched using keywords for all key concepts.Specific search strategies are listed in Table 1.The database search was limited to the period between January 1,2000 and August 31,2021.The 2000 start date was chosen to allow international comparisons and to capture any preliminary Australian work,because the first edition of the NSQHS Standards was released in Australia in 2011,and comprehensive care has been used internationally for a longer period.Based on the references included in full-text screening,we identified countries(i.e.,Australia,the United Kingdom [UK],Norway,Canada,and the United States of America[USA])that may have a national standard for comprehensive care and associated emerging terms (i.e.,individualised care plan,individualised plan,personalised care).To locate relevant grey literature (i.e.,government reports and webpages),we performed country-specific searches on Google and international government/organisation websites using the existing and emerging terms on October 28,2021 (see details in Appendix A).Database search and grey literature search were updated to include the more recent research available up to January 31,2023.Additionally,we searched the reference lists of the included papers for any potentially relevant primary studies,reviews,and government reports and webpages.We also searched the papers published by the authors whose articles had been included in the review.To better understand the context in which the standards for comprehensive care have been implemented,demographic,economic,and health service utilisation for each identified country were also investigated and described.

Table 1 Key concepts and search strategy.

2.3.Literature selection

The results of computerised searches were downloaded to Endnote,and duplicates were removed.Publication titles and abstracts were then uploaded to Covidence,and any additional duplicates were also removed.The eligibility criteria for literature selection,including the operational definitions of “comprehensive care” and “national standard”,are presented in Table 2.The operational definition of “implementation” involves the actions,steps,or strategies employed to introduce,adopt and execute a national standard,including elements such as policy development,resource allocation,education and training,monitoring and evaluation.“Impacts” refers to the specific measures or indicators used to assess and evaluate the effects or consequences of implementing a national standard,such as changes in clinical processes,patient outcomes (e.g.,hospital-acquired complications,mortality rates,readmission rates),patient satisfaction,resource utilisation,and healthcare provider adherence to the standard.

Table 2 Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Using the eligibility criteria (Table 2),literature selection was conducted in two stages:Stage 1,title and abstract screening;Stage 2,full-text screening.Two authors(BX,MMK)worked as a pair and independently reviewed the titles and abstracts,followed by the full-text papers that were deemed relevant.Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or in discussion with the third author(CS) if required.

2.4.Quality appraisal

The quality assessment of included articles was performed using Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools [15].JBI Critical appraisal tools have been developed through collaboration between JBI and its partners,and endorsed by the JBI Scientific Committee after undergoing rigorous peer review.It covers appraisal guidance for various types of articles.Quality reviews of included articles were undertaken by two independent reviewers(BX,MMK),and disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion and mutual agreement.Quality ratings for each article are provided in Appendix B Table S1.Because the aim was to synthesise a body of literature to provide a picture of national standards for comprehensive care worldwide,studies were not excluded based on quality assessment.

2.5.Data extraction

Our study aimed to explore the implementation approaches,challenges and facilitators,and impacts of a national standard for comprehensive care internationally.To facilitate comparisons we used the same extraction template for each article reviewed,using the Australian NSQHS Comprehensive Care Standard [7] as a framework.The template includes information on the release year,title,aim,governing body,scope,status,service receivers,coordinator,and implementation framework,resources challenges and facilitators,and impacts of each identified standard.For each article reviewed,we also extracted information on year,country,author,article type,target audience,aim,contribution,and conclusion.Data extraction was executed by one author(BX) and reviewed by all authors.

2.6.Data analysis

The extracted data were managed via Excel spreadsheets.The studies included were heterogeneous in nature owing to the diverse methodology involved,making it unfeasible to pool quantitative data.Therefore,a qualitative content analysis [16] of theextracted data was conducted.A concept-driven approach was employed in the analysis,whereby a predefined set of codes (i.e.,components of a standard,implementation approaches of a standard,factors affecting the implementation of a standard,impacts of implementing a standard)aligned with the research questions was used to systematically assign codes to the qualitative data in a structured manner.Quantitative data from individual studies were reported when applicable,whilst ensuring the rigour and comprehensiveness of the synthesis of information.

3.Results

Through the systematic search,a total of 7,978 non-duplicate articles were identified,of which 7,926 were excluded during the title and abstract screening stage.The full texts of the remaining 52 articles and 12 articles identified from other sources were reviewed,of which 48 were excluded after the full-text screening.Finally,16 articles were included in this review.The reasons for exclusion and the numbers included/excluded are described in the PRISMA flowchart (Fig.2).

Fig.2.PRISMA flow diagram of the selection process for articles related to the national standards for comprehensive care.

3.1.Characteristics of included articles

Of the 16 included articles,5 were primary studies (3 quantitative studies and 2 qualitative studies).Three countries(Australia,Norway and the UK) were identified as having national standards for comprehensive care(Appendix B Table S2).

3.2.Countries with national standards for comprehensive care

As shown in Appendix B Table S3,the three countries vary greatly in population with the UK,Australia,and Norway having a population of 67.1,25.7,and 5.4 million,respectively[17].Australia has a slightly lower percentage of the population over age 65 and a lower mortality rate than Norway and the UK.Australia spent a lower percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP)on health than Norway and the UK,but it has more acute care hospital beds per capita and a shorter average length of stay for acute care than Norway and the UK.As shown in Appendix B Table S4,the three countries all have national healthcare systems,which offer automatic and universal coverage for primary healthcare [18].Approximately half of the Australian adult population has private supplementary insurance,while in the UK and Norway,it is only about 10%.Unlike Australia and Norway,the UK mostly has casebased payments,which is a way of funding according to the cases treated rather than per service or bed days.

3.3.Overview of national standards for comprehensive care

Australia introduced the “Comprehensive Care Standard”(Table 3)as part of the NSQHS in 2017 for uptake in 2019[19].This standard was developed and released by the ACSQHC,which is a corporate Commonwealth entity and part of the Australian Government Department of Health.The Comprehensive Care Standard is mandated in all public and private hospitals,day procedure services and public dental services across Australia [20].Some other health service organisations may be required to implement the Comprehensive Care Standard due to funding arrangements.

Table 3 Summary of identified countries that have a national standard for comprehensive care.

Norway introduced the “Individual Care Plan” (Table 3),a mandatory multidisciplinary plan for individual care,by law in 2001[21].It was included in the Patient Right Act in 2001 and the Act related to social services in 2005[8].The Norwegian Directorate of Health is the authority of administrating,applying and interpreting legislation and regulation in areas of health policy.The Individual Care Plan is provided in all settings where health and care services are provided [22].Different parts of the health and care service are required by laws to cooperate on an individual care plan and care coordination [23].

The UK introduced “Personalised Care” (Table 3) by National Health Service (NHS),as one of five key priorities within the NHS Long Term plan in 2019 [24].Resource allocation and oversight in the UK were delegated to NHS England,an arms-length body,by the Health and Social Care Act 2012(an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom).NHS England and NHS Improvement,as a new single organisation since April 2019,have been working together to better support care delivery.Personalised Care was set to be implemented through 21 Personalised Care demonstrator sites.Each site implements Personalised Care at a local-level scale.The delivery of Personalised Care aims to reach 2.5 million people by 2023/24 and the aim is to double by 2028/29.

3.4.Components of national standards for comprehensive care

As specified in the Australian Comprehensive Care Standard,comprehensive care is delivered to all patients in acute care hospitals,including patients at the end of life[25].Comprehensive care planning commences after the clinical assessment and diagnosis[25].More in-depth risk screening and assessment will inform the development of a comprehensive care plan with the patient.A comprehensive care plan is a single document describing the agreed goals of care,and outlining identified risks,actions taken and key treatment information for a patient to achieve those goals[25].Information should be together in an accessible format.No default template or content was required for the comprehensive care plan.Nine key components of a comprehensive care plan were recommended to be included in comprehensive care plans [25].The Comprehensive Care Standard contains a unique component of minimising patient harm including actions related to falls,pressure injuries,nutrition,mental health,cognitive impairment,and endof-life care.However,the Comprehensive Care Standard does not cover detailed information about the care coordinator[26].

The Norwegian Individual Care Plan is delivered to patients with long-term and complex needs for coordinated care in acute care hospitals,including children[8,22].For the Individual Care Plan,the planning process needs to be initiated promptly upon request from any party,including the patient,next of kin or legal guardian.An individual care plan includes an outline of the patient’s goals of care,along with the necessary objectives,resources and services required for meeting various aspects of their needs,independent of diagnosis,age or level of care[21].The plan indicates the allocation of responsibility between the patient and various professionals,along with a schedule for implementation[8].No default template was required for an individual care plan except for the content for the individual care plan specified in Norway’s health and social care legislation[23].In Norway,it is statutory that all municipalities and health trusts must have a coordinating unit for habilitation and rehabilitation [22].This unit is given overall responsibility for the work with the individual plan and the appointment,training and supervision of the coordinator,preparation of procedures and more.A coordinator must be appointed among the serviceproviders,giving priority to the preferences of the patient and user when selecting one.Even if the patient and user do not desire an individual care plan,a coordinator should still be offered.

British Personalised Care not only supports people with longterm health conditions or complex needs in acute care hospitals,but it takes whole-population approaches to support people of all ages and their carers to manage their health and wellbeing and make informed decisions and choices[24].Personalised Care has a unique component of personal health budgets and integrated personal budgets.The personalised care and support plan(PCSP)is developed following an initial comprehensive assessment [27].There is no set template for the PCSP,but it has to meet five criteria[27].As specified in Personalised Care,each person has a single,named care coordinator,but the detail of the care coordinator is not given [24].

3.5.Implementation approaches of national standards for comprehensive care

In Australia,a conceptual model was developed by ACSQHC to support the implementation of the Comprehensive Care Standard in acute care hospitals.This model categorised the organisational requirements necessary to support the delivery of comprehensive care into three domains (Table 3) [26].ACSQHC also specified four criteria for implementing the Comprehensive Care Standard(Table 3) [25].ACSQHC has developed implementation guides,accreditation workbooks,online courses,and other resources to help health service organisations to meet the Comprehensive Care Standard [28-30].An accreditation scheme and a survey study were used to evaluate the implementation of the standard[28,29].

Norway does not have a defined framework for implementing the Individual Care Plan in acute care hospitals.Norway published laws,regulations,and national guides to guide the delivery of the Individual Care Plan.The Norwegian Directorate of Health developed guidelines,provided mandatory training programs,and initiated projects to inform care professionals and managers about the Individual Care Plan and to ensure that proper planning processes were followed by both hospitals and municipalities [21].

A comprehensive model of Personalised Care was developed in the UK to make personalised care ‘business as usual’ across health and care [24].This model comprises six key components or programs (Table 3),and each is defined by a standard.NHS England also developed a delivery plan that listed 21 actions to roll out Personalised Care across England [24].NHS has developed guidelines and accredited personalised care training programs for general practitioners,nurses and allied health professionals.A virtual organisation,the Personalised Care Institute,is responsible for setting the standards for evidence-based training in personalised care in England.

3.6.Factors affecting implementation of national standards for comprehensive care

A range of factors has been found to affect the implementation of the Australian Comprehensive Care Standard in acute care hospitals.Murgo et al.’s (2022) [28] evaluation of the assessment outcome data of health service organisations revealed underperformance in implementation and identified common issues experienced by organisations.These issues include difficulties in implementing governance processes,demonstrating effective care planning,and implementing end-of-life care actions and some minimising harms actions.ACSQHC’s (2022) [29] survey study identified the challenges of implementing the Comprehensive Care Standard,with developing a comprehensive care plan being the most challenging due to reasons such as no standard care plan used by all disciplines and difficulties in care planning with a multidisciplinary team (MDT).Patersen et al.(2022) [31] implemented a new care plan template to meet the requirement of the Comprehensive Care Standard.They found the aspects that worked well in practice included efficient structure of the documentation,using the Identify,Situation,Background,Assessment and Recommendation (ISBAR) framework for handover,and promoting clinical decision-making and direct patient care.On the other hand,the aspects that did not work well in practice included patient signature on the daily care plan,lack of MDT involvement supported by the documentation,excessive documentation of paperwork,and patient-centred goals not being captured in the documentation.

Two peer-reviewed papers that examined the implementation of the Norwegian Individual Care Plan in acute care hospitals were found[8,21].Bjerkan et al.’s(2011)[21]questionnaire study of the use of individual care plans revealed that the deployment of individual care plans did not cover the expected proportion of the population.This was independent of the municipalities’ size,political government,funding situation,or planning process of the plan.The planning process was mostly managed by local health and social care professionals,rather than hospital staff and general practitioners.Bjerkan et al.’s (2014) [8] interview study reported that if either users or care professionals (or both) were proactive,care planning worked well.If neither users nor care professionals were proactive,no planning activities occurred.It was important to make both patients and care professionals see the planning process as meaningful and develop the technical skills required for webbased collaboration.

No publications were identified that reported on the implementation of British Personalised Care.

3.7.Impacts of the standards for comprehensive care

Only one peer-reviewed paper that examined the outcome of the Australian Comprehensive Care Standard in acute care hospitals was found [32].Oberai et al.(2021) [32] reported that the implementation of the tailored delirium intervention increased adherence to the Comprehensive Care Standard and led to a gradual decrease in the rate of delirium in patients aged 65 years and over admitted to the hospital with a hip fracture.In this study,there was 33.6% adherence to the Comprehensive Care Standard after the implementation in 2019 compared to 4.7% before the implementation.Findings suggest more work is required to further increase adherence.The research also highlighted the importance of exploring whether adherence varies in particular populations,such as non-English speakers.Paterson et al.(2022) [31] found that patients had high satisfaction with person-centred care and variable involvement in their daily care plan.However,they also found that communication between clinicians and patients was sometimes insufficient,and patients experienced a lack of integration between MDTs.

No publications were identified that examined the explicit outcomes of the Norwegian or British comprehensive care related standards.

4.Discussion

Australia,Norway,and the UK were identified as countries having national standards for comprehensive care in acute care hospitals.The three countries vary greatly in population size but are similar in the percentage of the population over age 65 and life expectancy.Australia spent a lower percentage of GDP on health and had a shorter average length of stay for acute care than Norway and the UK.The three developed countries have a national healthcare system and a decentralised trusteeship structure.However,some differences existed between the structure and implementation of the standards across the three countries.

In Norway,the standard is intended for patients with long-term and complex needs.This is currently the same in the UK.They intend to extend this to all patients,but the date is uncertain.In Australia,the Comprehensive Care Standard already applies to all patients,showing a move towards inclusiveness by ensuring that standards for comprehensive care are guiding the care of all patients.However,there is no evidence to indicate whether implementing standards for comprehensive care will benefit all patients,especially regarding the economic effects[5,33].Future studies are needed to explore the effects of implementing a national standard for comprehensive care among all patients.This will help policymakers in other context to understand the potential benefits and challenges of implementing such standards and inform their decision-making.

The evidence from Australia suggests there is an opportunity to incorporate specific harms,including falls,pressure injuries,cognitive impairment,malnutrition,self-harm and suicide,violence and aggression,and seclusion and restraint,into patient care plans to ensure that patients are receiving safe and highquality care in acute care hospitals.These specific harms are common in acute care hospitals and can cause serious consequences [34],and incorporating them into care planning has the potential to develop targeted interventions to address them.However,due to the current lack of evidence regarding the impacts of addressing them in a national standard for comprehensive care,there is an opportunity to explore the effect of the Australian Comprehensive Care Standard on these specific harms in the future.

A care plan is a document describing agreed goals of care and outlining planned activities for a patient.It is intended to strengthen the coordination between care professionals and the patient [8].The three countries specified that patients only have one integrated care plan,and no default template was required.The focus of a care plan is not its form,but the shared decision-making with patients,carers and families to achieve their goals of care.Norway’s health and social care legislation specified the content of the Individual Care Plan.However,in Australia and the UK,the type and the content of the plan are expected to vary depending on the complexity and needs of the patient,the setting,and the type of service.Given the common challenges in developing a standard care plan,policymakers,healthcare providers,and researchers could consider developing a compatible template that could be adapted to different patients,settings,and types of services to improve care coordination and delivery.

Information about a care coordinator varies greatly among these three countries.The Comprehensive Care Standard does not cover information about a care coordinator,considering that allocating an official care coordinator for every patient may not be feasible[26].It does recognise that delivering safe and high-quality comprehensive care requires a distinct care coordinator assigned to support the patient care journey[26].Norway has specified a care coordinator for the Individual Care Plan in the laws and regulations.NHS has mentioned a care coordinator but does not specify more details.However,a lack of instruction,training,and specified care coordinators may cause the underuse of the standards [35].Future studies are needed to understand how to optimise care coordinators’ role in implementing the standards,and whether different approaches have had an impact on effectiveness.

The legislation progress of the standards for comprehensive care differs among these three countries.In Australia,there is no direct legislation governing the accreditation process used to assess and guarantee the implementation of the Comprehensive Care Standards.There is a provision for legislative oversight through funding mechanisms that require accreditation and can impose various sanctions if standards are not met (including administrative oversight by the regulator,loss of licenses and/or loss of funding) [2].Norway has included the standard in laws and regulations.Personalised Care was set out in the NHS Long Term Plan and its legislation is still in progress in the UK.The change set out in the Long Term Plan started by voluntary effort and empirical experiment,then establishes itself by merit,and ultimately the State steps in and makes it a universal service [36].The legislation would support more rapid progress in implementation [36].Strength in legislation development needs to be matched by strength in the implementation of the standards for comprehensive care to achieve desired outcomes.There is no evidence to indicate whether the Norwegian or UK way is better for implementing the standards for comprehensive care.

Australia and the UK have a defined framework and published explicit guidelines on implementing the national standards for comprehensive care,while Norway does not.Australia has the ACSQHC and the UK has NHS England to govern their standards.Norwegian Health Authorities used a dissemination strategy to implement the Individual Care Plan,but without comprehensive guidelines on how managers within health and social care should carry out further implementation in their organisations [37].The dissemination strategy is a targeted distribution of information,mainly written,to spread information about laws and regulations to health and social care workers [37].This strategy is not necessarily a systematic use of strategies to introduce the Individual Care Plan.Previous literature indicates that passive dissemination of information is generally ineffective when it comes to the implementation of changes [38].In order to have a more effective implementation,countries like Norway may benefit from the design of a systematic strategy and defined frameworks and structures in the implementing a national standard for comprehensive care.

The Norwegian Individual Care Plan,the first national standard for comprehensive care introduced in 2001,involves a collaboration of health care and social care services across sectors after 2005.In the UK,Personalised Care,introduced in 2019,takes a wholesystem approach,integrating services around the person including health,public health,social care,and wider services[24].In Australia,the Comprehensive Care Standard,introduced in 2017,is targeted at hospitals and similar health services and does not appear to link directly to social care,which may limit the role of the care coordinator and care plan.There was some reporting of implementation work in Norway[21],but more research is needed to explore solutions for improved care standard implementation.There is limited evidence showing the impacts of the national standard for comprehensive care on patient outcomes in any of the three countries identified through this literature review.Follow-up research needs to be undertaken to understand the impact of health policy on health services and patient outcomes.

5.Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this review include a rigorous and systematic search strategy.To our knowledge,these findings provide a unique overview of current evidence of addressing policy,implementation,and impacts of national standards for comprehensive care globally.Two papers were excluded because they were not able to be translated in a timely manner for this review and other publications may have been missed due to different terminologies not being picked up by the authors despite due diligence.The international evidence presented is limited to comparisons among three countries (Australia,Norway,and the UK),as these were the only countries identified with national standards for comprehensive care in acute care hospitals based on our search strategy and criteria.Although it is a synthesis of articles mostly made up of nonresearch evidence,the best available evidence has been included.As McArthur et al.(2015) [39] pointed out,“systematic reviews of text and opinion may be considered as legitimate sources of evidence,especially when there is an absence of other research designs”(p.195).Results of the literature search indicate several gaps in research regarding national standards of comprehensive care which highlights the time-sensitive need for more policy-based research following the recent introduction of the new standards in Australia and the UK.The scarcity of research papers evaluating the national standard for comprehensive care may be attributed to several constraints,both methodological and political,in realworld public policy evaluations.The widespread nature of the national standard would have made experimental designs unfeasible,further complicated by the concurrent or sequential implementation of multiple standards.The rapid implementation and poor data availability would also have hindered comprehensive assessments.Hospitals’ cautious approach and the fear of negative evaluation results likely added to the lack of research.Addressing these challenges and fostering collaboration between researchers and health authorities can improve the quality and depth of policy evaluations in the future.

6.Conclusion

Although comprehensive care has become a central theme in healthcare worldwide,only Australia,Norway,and the UK were identified as having national standards for comprehensive care.Differences in the components and implementation of the national standards for comprehensive care among these countries holds significant implications for policymakers,healthcare providers,and researchers,and the insights gained from this study can be generalised to other contexts.Policymakers should take into account the specific needs and challenges of their own countries when formulating and implementing national standards for comprehensive care.Findings from this study revealed a gap in the literature reflecting knowledge about the implementation challenges,and the impacts of the standards of comprehensive care.There is the opportunity to examine the factors affecting the implementation of the national standards for comprehensive care and its effects on patient outcomes in both Australia and the UK given the more recent requirement for implementation in 2019.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was not required for this study as it is a review of existing published data.

Funding

Beibei Xiong is supported by Graduate School Scholarships from the University of Queensland.This work is part of the project“Improving quality of care for people with dementia in the acute care setting (eQC)” which is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council of the Australian Government (ID:APP1140459).The research was designed,implemented,and analysed independently,with no involvement from the funding organisation.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Beibei Xiong:Conceptualization,Methodology,Validation,Formal analysis,Investigation,Data Curation,Writing -original draft,Writing -review &editing,Visualization,Project administration.Christine Stirling:Conceptualization,Methodology,Formal analysis,Writing-original draft,Writing-review&editing,Supervision.Melinda Martin-Khan:Conceptualization,Methodology,Validation,Formal analysis,Investigation,Resources,Writing-original draft,Writing -review &editing,Visualization,Supervision,Funding acquisition.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Appendices.Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2023.09.008.

International Journal of Nursing Sciences2023年4期

International Journal of Nursing Sciences2023年4期

- International Journal of Nursing Sciences的其它文章

- Relationship between nurses’ perception of professional shared governance and their career motivation: A cross-sectional study

- 《国际护理科学(英文)》2024年征稿

- The associations among nurse work engagement,job satisfaction,quality of care,and intent to leave: A national survey in the United States

- Nurse-coordinated home-based cardiac rehabilitation for patients with heart failure: A scoping review

- Effectiveness of a family-based program for post-stroke patients and families: A cluster randomized controlled trial

- A psychometrics evaluation of the Thai version of CaregiverContribution to Self-Care of Chronic Illness Inventory Version 2 in stroke caregivers