别让丑角入场:寻找真正的真实主义

司马勤

一个多世纪以来,波特罗·马斯卡尼的《乡村骑士》(Cavalleria Rusticana,1889)和鲁杰罗·莱翁卡瓦洛的《丑角》(I Pagliacci,1892),一直像美国人在早餐中将花生酱配果冻一样搭配在一起——或者,以其他國家的饮食习惯为例,类似猪肉配卷心菜或香肠配土豆泥——但这种搭配并不是完全不可分离的。两部作品的“初次约会”是在1893年的纽约大都会歌剧院,如今偶尔各自还会搭配其他的剧目上演——我第一次观赏《丑角》是在一个大学制作的演出中,当时是与普契尼的独幕喜剧《贾尼·斯基基》(Gianni Schicchi)共度一晚——但几乎每个人都认为《乡村骑士》和《丑角》是绝配。

这主要是因为,尽管它们的故事背景不同,然而事实证明两部作品非常契合。两部剧的时长都约75分钟(虽然它们都被称为“独幕剧”,但严格意义上来说《丑角》有两幕),也基本上都是两位作曲家为当今观众所知的唯一作品(尽管类似总部位于伦敦的著名歌剧团体Opera Rara等组织一直在致力于发掘两位作曲家其他作品,安排高质量、高知名度的歌剧制作或录音)。

《乡村骑士》和《丑角》中的合唱和咏叹,精彩程度不相上下,两者都成为真实主义歌剧中的经典——用一位评论家的话来说,真实主义歌剧是一种短暂流行的意大利歌剧流派,“用社会最底层家庭的通奸、引诱、谋杀和自杀,取代了贵族阶层的通奸和引诱、谋杀和自杀”。

然而,如今真实主义歌剧可能很难再被接受。尽管其名字是含有“真实”之意的词根,但真实主义歌剧比起戏剧化风格的演绎更不“真实”。与意大利新现实主义一样——这场于真实主义歌剧半个世纪后出现的一场以电影为主导的运动,旨在戏剧化地表现社会问题——真实主义歌剧的特征虽然容易识别,但与今天的戏剧习惯完全不一致。

那么,你如何将这两个完全不同的故事串联起来,同时又能让这种风格看起来很现代呢?在今年早些时候希腊国家歌剧院的新制作中就尝试过其中的一种方法,即在上演《乡村骑士》和《丑角》时,将一个装饰有非洲图案的巨型风车放置在舞台中央,并在两侧环绕着两个巨大的红色罂粟花温室。

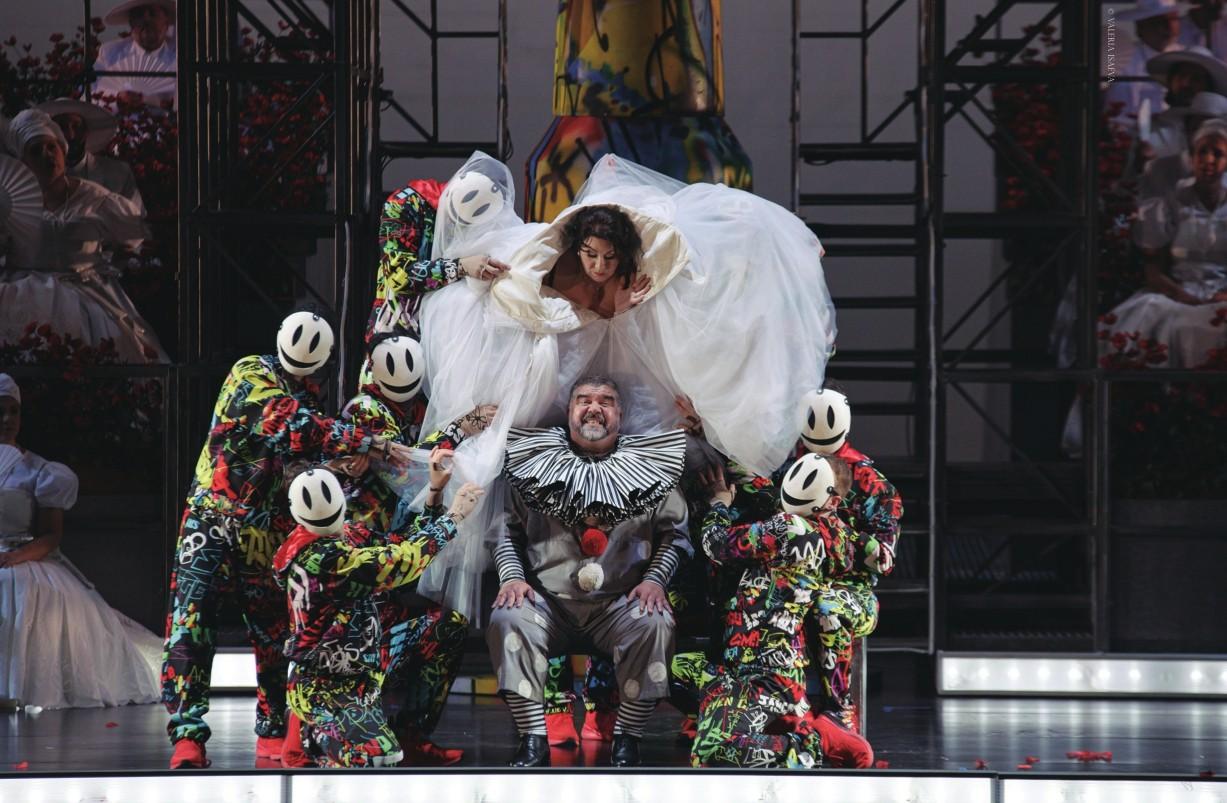

导演尼科斯·卡拉塔诺斯(Nikos Karathanos)备受赞誉,是因为消除神圣和世俗的陈词滥调并不容易。他的《乡村骑士》中没有清晰可辨的教堂,《丑角》中也没有“戏中戏”的舞台——尽管这并不意味着他完全抛弃了原著中的宗教戏或后台戏。事实上,《乡村骑士》中有大部分内容都融入了希腊东正教意象,尤其是大量的狂欢节装饰和一个围着缠腰布、头戴荆棘王冠的形象。《丑角》则散发着它独特风格的戏剧文化,一群持着枪踢足球的恶棍看起来很像歌舞伎中的忍者,但是又放弃了传统的黑色忍者服,改为身着充满涂鸦的彩色服装。

你这下明白了吧,没有人会把这个场景误认为是一个意大利村庄,或者是19世纪末的那个时代。但是,即使在当晚最愚蠢和最无关紧要的时刻——舞台上几乎没有任何宣叙调的呈现——莱斯利·特拉弗斯(Leslie Travers)的布景和服装设计成功地将这晚的两个部分融合在一起,让人们认为这实际上是发生在同一地点不同时间的两个片段。与此同时,指挥安托内洛·阿莱曼迪(Antonello Allemandi)在乐池中以完全合乎逻辑的真实主义风格,将希腊国家歌剧院管弦乐队和合唱团的力量结合在一起。

演唱也循规蹈矩,总是与舞台表演格格不入,但演员却为观众提供了一些引人入胜的串联元素。男高音歌唱家亚森·索格霍莫尼扬(Arsen Soghomonyan)在希腊国家歌剧院首秀,也是第一次在《乡村骑士》中饰演图里杜;之后,他又在《丑角》中饰演卡尼奥。他所塑造的两个角色引人注目——首先是一个诱惑者,然后是一个因嫉妒而杀人的丈夫(尽管索格霍莫尼扬饰演的卡尼奥并不像一个小丑)。

男中音迪米特里·普拉塔尼亚斯(Dimitri Platanias)在上下半场中,都成功地演绎了在犯罪边缘游走的阿尔菲奥和托尼奥。女歌者中,最强的表现也提供了最大的反差。叶卡捷琳娜·古班诺娃(Ekaterina Gubanova)在《乡村骑士》中热情洋溢的桑图扎(也是她第一次演唱该角色),与塞莉娅·科斯泰(Cellia Costea)在《丑角》中活泼的内达有着鲜明对比。两人都充分把握了作品的风格,但无奈两人的音色都过暗,发声技巧又都太丰富,在舞台上饰演年轻的农民形象缺乏可信度。

这种做法与几个月前我在世界另一端的新加坡看到的演出截然不同——尽管两者都有一个共同点。虽然《乡村骑士》和《丑角》可能已经捆绑演出了几十年,但直到最近,才出现在同一个晚上由同一位歌手在这两部剧中同时出演的情况。去年11月,新加坡抒情歌剧院不仅请到了多米尼加青年男高音何塞·埃雷迪亚(José Heredia)在《乡村骑士》中饰演图里杜、在《丑角》中饰演卡尼奥,请到了新加坡男中音吴翰卫(Martin Ng)出演阿尔菲奥和托尼奥,还邀请了意大利裔美国女高音丽莎·阿尔戈齐尼(Lisa Algozzini)出演桑图扎和内达。

这场冒险出乎意料地取得了成功,这在很大程度上是因为导演阮妙芬(Nancy Yuen)对于制作的其他考虑都十分谨慎,绝不疏忽。舞台中央是一个简单的平台(用作《丑角》中的舞台),周围有两个柱子(《乡村骑士》的主要装饰)。由于视觉干扰很少,歌手们可以放弃通常的歌剧架势,更多地专注于他们所需演绎的不同角色的微妙之处:埃雷迪亚的图里杜明显没有平时那么有男子气概,他的卡尼奥比起经典演绎的嫉妒更加充满绝望;阿尔戈齐尼的桑图扎和内达站在通奸行为的对立方(先是受害者,然后是施害者);吴翰卫从一个凶神恶煞的阿尔菲奥变成了一个笨拙无能的托尼奥,声音沉着冷静。

但也許促成当晚演出成功的最大因素是管弦乐的规模。指挥家陈康明(Joshua Tan)娴熟地指挥着一个12人合奏团,在丹尼尔·詹姆斯(Daniel James)精湛的缩编中,音乐线条从未显得苍白无力,也很少让歌手们超出他们的舒适区。尽管在《乡村骑士》的结尾表现出些许紧张,但埃雷迪亚在《丑角》中的嗓音强度从未减弱。同样来自国际的配角阵容也表现出了扎实的表演。唯一的不确定性来自成人和儿童合唱团,尽管一出场有些粗糙,最终他们还是设法用音乐填满了舞台。

“连一个完整的管弦乐队都没有?”我似乎已经可以听到正统主义者的抱怨了。但新加坡的制作显然是有一些可圈可点之处的。雅典人在音乐风格上可能具有明显的优势,但他们的戏剧性往往缺乏重点和明确性。雅典的舞台上挤满了经验丰富的歌手,而新加坡的表演者们则充满了青春活力。至于那些偶尔加入的地方戏……嗯,很难评论新加坡的《丑角》,毕竟这原本说的就是一个关于地方剧团的故事。

你甚至可以说,这才是真正的真实主义。

Pietro Mascagnis Cavalleria Rusticana (1889) and Ruggero Leoncavallos I Pagliacci (1892) have been paired together like peanut butter and jelly—or, depending on your culinary traditions, pork and cabbage or bangers and mash—for more than a century, but the match was hardly inevitable. The two first met on a blind date in New York at the Metropolitan Opera in 1893 and still occasionally see others—I first experienced Pagliacci in a university production sharing an evening with Puccinis one-act comedy Gianni Schicchi—but pretty much everyone still considers them a couple.

This is largely because, despite their different backgrounds, the two have proved remarkably com- patible. Both shows run about 75 minutes (despite both being generally described as “one-acts,” Pagliacci technically has two), and both are essentially the only works of either composer that audiences today know by name (though organizations like the London-based Opera Rara have been offering high-quality, high-profile productions and recordings of the composers other operas).

Both Cavalleria and Pagliacci display choral writing on par with their finest solo moments, and both became instant classics in the verismo repertory—a short-lived Italian genre that, in the words of one critic,“replaced adultery, seduction, murder and suicide in the highest families with adultery, seduction, murder and suicide in the lowest families.”

Verismo, though, can be a hard sell these days. Despite the roots of its name, verismo is less “real” than just a particular form of theatrical stylization. Like Italian neorealism, a predominantly cinematic movement that emerged half a century later to dramatize social concerns, the earmarks of verismo are both easy to recognize and wholly at odds with dramatic idioms today.

So how can you link these two disparate stories while also making the style seem current? One approach not attempted until the Greek National Operas new production earlier this year is to place a giant windmill decorated with African patterns at center stage for both productions and surround them on either side with two giant hothouses of red poppies.

To give director Nikos Karathanos some credit, its not easy to eliminate clichés of the sacred and profane. Theres neither a recognizable church in his Cavalleria nor a “stage” stage in his Pagliacci—though that doesnt mean he completely forsakes religion or backstage drama. Much of Cavalleria, in fact, is seasoned with Greek Orthodox imagery, not least being an abundance of Carnival decor and a beleaguered figure wearing a loincloth and a crown of thorns. Pagliacci exudes its own culture of stylized theatricality, with a group of gun-toting, football-playing ruffians resembling the ninja-like kuroko of kabuki, here eschewing their traditional black attire for colorful graffiti-filled garb.

You get the idea. No one would ever mistake the setting for an Italian village, or its time period for the late 19th century. But even in the evenings silliest and most irrelevant moments—very little of the dialogue being sung is actually represented on stage—Leslie Traverssets and costumes manage to blend both parts of the evening together as essentially two episodes occurring at different times in the same place. At the same time, from the orchestra pit, conductor Antonello Allemandi held the combined forces of the Greek National Opera Orchestra and Chorus together coherently in fully legitimate verismo style.

The singing, too, was practically the picture of tradition, often placing it rather at odds with the staging. The casting in particular offered some intriguing through lines. Tenor Arsen Soghomonyan, making his company debut and first professional appearance as Turiddu in Cavalleria, returned to the stage as Canio in Pagliacci to make a strong dramatic arc, first a seducer, then a jealous, murderous husband (Soghomonyans Canio was not much of a clown).

Baritone Dimitri Platanias effectively portrayed both Alfio before intermission and Tonio afterward as borderline thugs. Among the women, the strongest showings also provided the biggest contrast. Ekaterina Gubanovas richly warm Santuzza in Cavalleria (also her first time to sing the role) stood at the opposite end of the vocal spectrum from Cellia Costeas bubbly Nedda in Pagliacci. Both were fully assured stylistically, yet both were way too dark in tone color and rich in vocal technique to be credible young peasants.

This approach was starkly at odds with a production Id seen only a few months ago halfway around the world in Singapore, though on one matter the two shared something in common. Cavalleria and Pagliacci may have split a billing for decades, but only recently have the same singers been expected to perform in both in a single evening. Last November, Singapore Lyric Opera featured not only the young Dominican tenor José Heredia as both Turiddu (in Cavalleria) and Canio (in Pagliacci) and the Singaporean baritone Martin Ng as Alfio and Tonio but also the Italian-American soprano Lisa Algozzini as Santuzza and Nedda.

The gamble paid off surprisingly well, in large part because director Nancy Yuen took so few chances with anything else. At center the stage was a simple platform (serving as Pagliaccis stage-within-a-stage) surrounded by two pillars (the primary ornaments for Cavalleria). With so few visual distractions, the singers could forego the usual operatic grandeur and focus more on the subtleties that marked their different characters. Heredias Turiddu was noticeably less toxically masculine than usual, his Canio full more of desperation than classic jealousy. Algozzinis Santuzza and Nedda stood on opposite ends of the adultery divide (first a wronged woman, then the woman doing the wronging). Ng went from a thuggish Alfio to a bumblingly inept Tonio with vocal aplomb.

But perhaps the greatest factor contributing to the evenings success was the scale of the orchestration. Conductor Joshua Tan deftly led a 12-piece ensemble behind the set, with musical lines (in Daniel Jamess superb reduction) that never seemed malnourished and rarely drove the singers past their comfort zone. Despite showing a bit of strain toward the end of Cavalleria, Heredias intensity in Pagliacci never flagged. Solid performances also came from an equally international supporting cast. The only tentative moments came from the adult and childrens chorus, who eventually managed to fill the stage musically despite a few rough entrances.

I can already hear the purists grumbling(“Not even a full orchestra?”), but the Singapore production was clearly on to something. The folks in Athens may have had a clear edge in musical style, but their theatricality was often unfocused and ill-defined. Where Athens was packed with veteran singers, Singapore offered performers brimming with the energy of youth. And as for some occasionally provincial theatrics…well, its hard to criticize Singapores Pagliacci, which is, after all, a story about provincial theatrics.

You could even say, thats real verismo.