Jewish Sources for Iconography of the Akedah/Sacrifice of Isaac in Art of Late Antiquity

Bonnie L.Kutbay

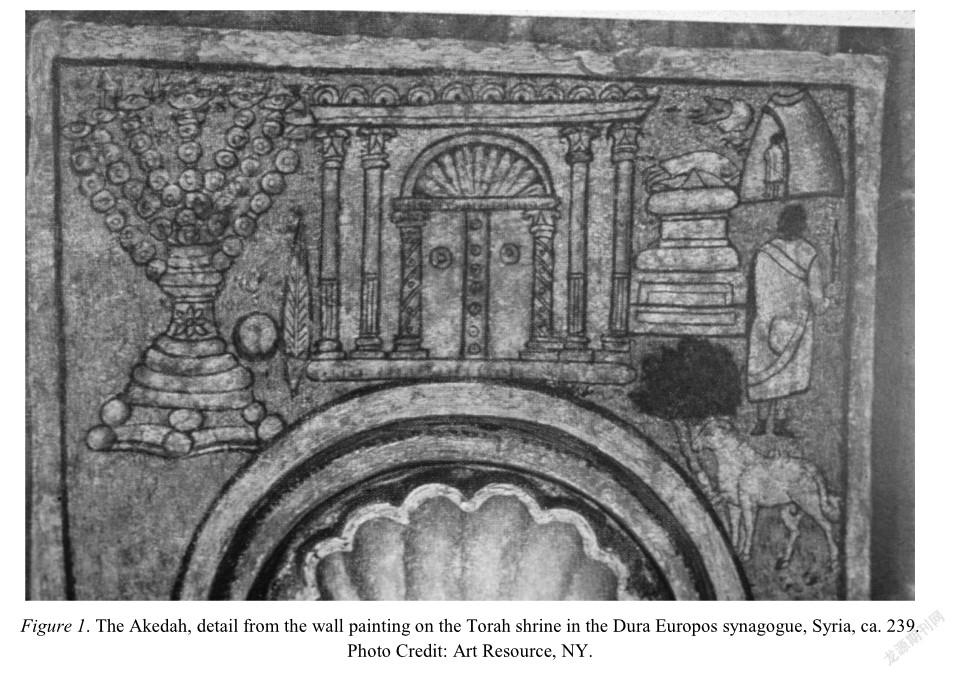

The earliest known image of the binding of Isaac, known as the Akedah, is on a Torah shrine in a synagogue in Dura Europos, Syria dating before 244 (fig. 1). It shows a fully developed iconography of a young Isaac on the altar with the burning wood, the ram by the tree, Abraham holding the knife, and the hand of God issuing from a cloud. Though the visual narrative is largely based on the account of the Akedah in Genesis 22, it also relies on details found in other Jewish literary sources that include the Talmud, Targum Onkelos, Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, commentary on Genesis by Rashi, Midrash account of Pirkei De Rabbi Eliezer, and Genesis Rabbah. This paper will present unexplored Jewish sources for the iconography of the Akedah/Sacrifice of Isaac in art of Late Antiquity.

Keywords: Akedah, Dura Europos, sacrifice of Isaac, Shekinah

Introduction

The earliest known image of the binding of Isaac, known as the Akedah, is on a Torah shrine on the western wall of the synagogue in Dura Europos, Syria dating before 244 (fig. 1) (Kraeling, 1956, pp. 346-363; Berman, 1997, p. 21; Gutman, 1987, p. 67).1 It shows a fully developed iconography of a young Isaac on the altar with the burning wood, the ram by the tree, Abraham holding the knife, and the hand of God issuing from a cloud.2 Though the visual narrative is largely based on the account of the Akedah in Genesis 22, it deviates slightly, borrowing details from other Jewish literary sources that include the Talmud, the Targum Onkelos, the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, the commentary on Genesis by Rashi, the Midrash account of Pirkei De Rabbi Eliezer, and Genesis Rabbah. The iconography of the binding/sacrifice of Isaac, first seen in the synagogue at Dura Europos, appears in all later Jewish and Christian art with some modification.

The Akedah in the Synagogue at Dura Europos

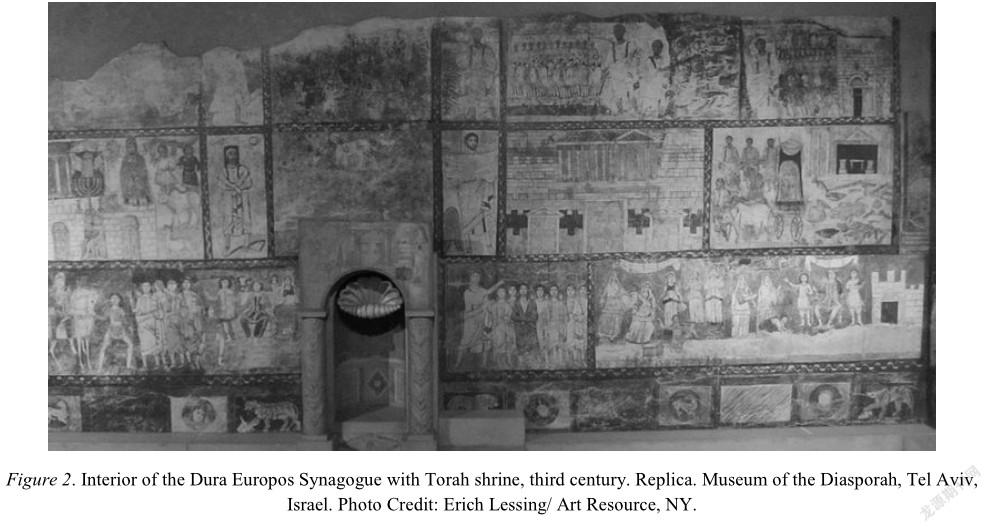

Originally a private house, the synagogue was part of a group of buildings located along the western wall street ca. 50-150 during Parthian rule (Kraeling, 1956, p. 327). Later, during Roman rule, 165-200, the house was converted into a place of worship. Commemorative inscriptions on ceiling tiles indicate the synagogue was renovated beginning 244-245.3 The assembly room, approximately 10 by 5 meters, and 7 meters high, was encircled by over thirty paintings of Old Testament stories in three registers on all four walls (fig. 2). On the western wall was the Torah shrine which portrayed the Akedah alongside images of the Jerusalem Temple, a lulav (palm branch), an etrog (citron), and a menorah.4 These are painted in a rectangular area measuring 1.47 meters wide and 1.06 meters high. The style of the decoration on the Torah shrine appears to date earlier than the surrounding wall paintings of ca. 244-245 (Fine, 2007, p. 38).5

Though Dura Europos provides the earliest known visual narrative of the binding of Isaac and with full iconography, the extent of its influence on later Jewish and Christian art remains uncertain since Dura Europos was buried by the Romans in their defense again the Sasanian attacks ca. 256 and remained buried until excavated in 1932 (Gutmann, 1988, pp. 25-29). We have no evidence who the artists were. They may have been Greek, Jewish, Persian, Roman, or Syrian since Dura Europos was a multicultural city. Located on the border of the Roman and Persian Empires, the city was marked by religious diversity. Whoever the artists were, most likely they were itinerant and carried their ideas with them from town to town, perhaps in pattern books, and this is how the visual formula spread to other areas. There is no evidence whether it first originated at Dura Europos or was conceived earlier at another synagogue now lost.

Nevertheless, surviving examples of the binding/sacrifice of Isaac in art of the third and fourth centuries strongly indicate that Jewish art first created the visual motifs that disseminated throughout the Jewish and Christian worlds. The Jews told the story first in the Torah. Isaac’s binding is such an important part of Jewish liturgy that was practiced in all synagogues. The story of the Akedah in Genesis 22:1-19, an example of faithful obedience, was read during the Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah. A shofar was blown several times during the reading of Genesis, referring to the ram that was substituted as the sacrifice in place of Isaac. Because of its long association with Jewish liturgy, the story of the binding of Isaac would easily have been presented in art first by the Jews, whether on plates, vessels, lamps, or floors and walls in synagogues.

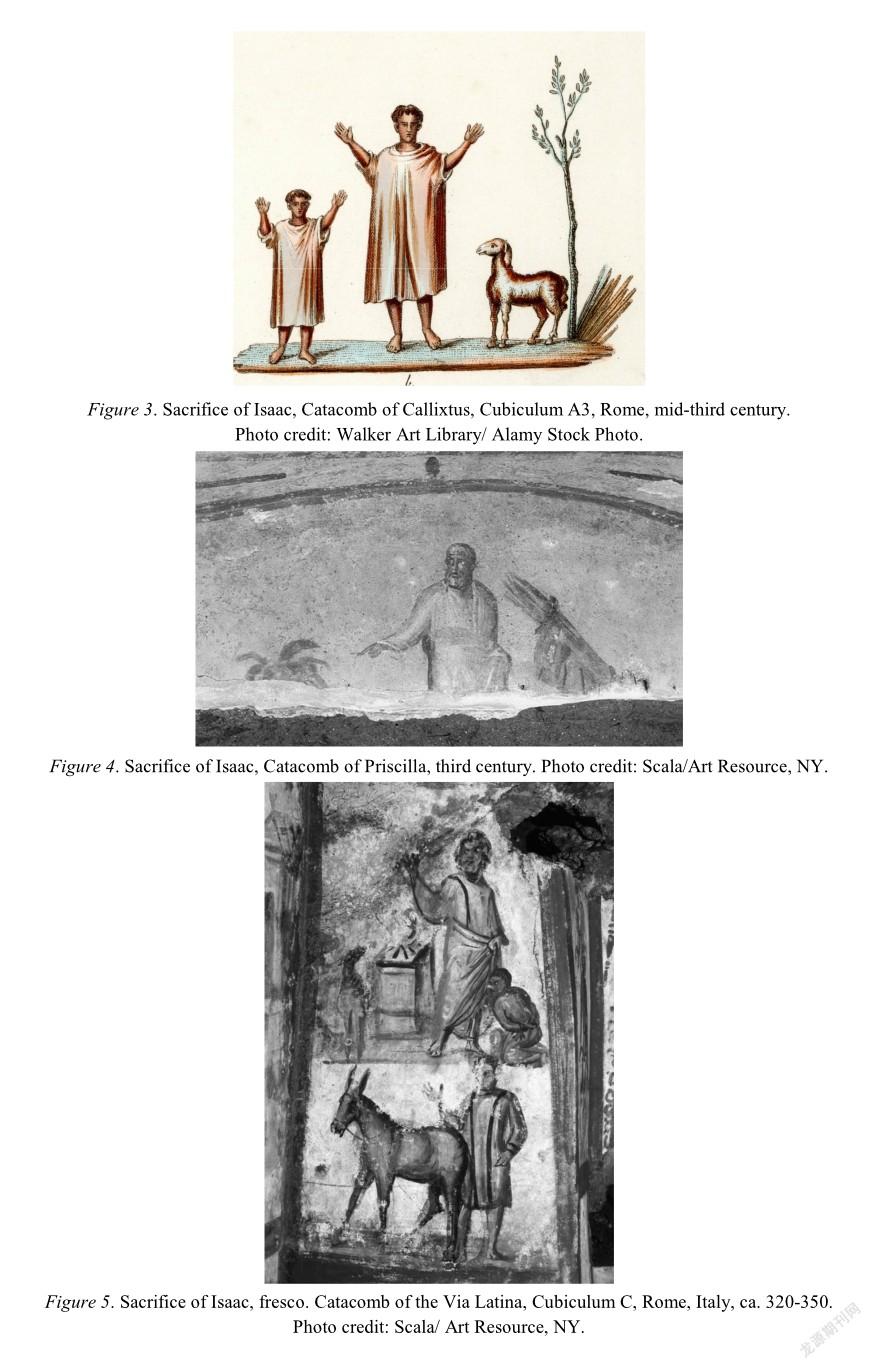

The Akedah in Dura Europos (pre-244) predates one of the earliest known Christian images of the Isaac story, known as the sacrifice of Isaac, from a fresco in the catacomb of Callixtus in Rome (fig. 3), dating from the mid-third century. It may also predate the third-century fresco of the sacrifice of Isaac in the Roman catacomb of Priscilla (fig. 4). Yet in both Christian examples, the iconography of the sacrifice is not fully developed, lacking the actual binding of Isaac. Full iconography occurs later in the fourth-century fresco of the sacrifice of Isaac in the Roman catacomb of the Via Latina (fig. 5) which presents an image of Isaac bound at the wrists. This formula continues in all future Christian and Jewish images of the sacrifice of Isaac.

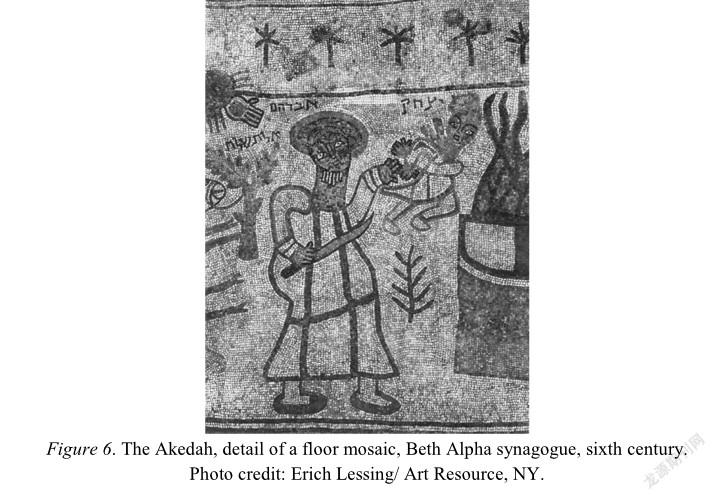

In later Jewish examples, though scarce, the Akedah is known from a floor mosaic in the Beth Alpha synagogue in Israel dating from the second half of the sixth century (fig. 6) (Sukenik, 1932; Gutmann, 1992, pp. 79-85), and a floor mosaic (badly damaged) in the synagogue at Sepphoris in Galilee dating from the fifth to seventh centuries (Weiss, 2000, pp. 48, 50-55, 58-61, 70). After these, there is no further evidence of the Akedah in Jewish art until the thirteenth century in Germany (Gutmann, 1987, p. 68).6

Jewish Motifs in the Iconography of the Binding of Isaac

Early Jewish literary sources on the Akedah and the earliest established iconography of the Akedah in art(first known at Dura Europos) had a major influence on specific motifs that appear in later Jewish and Christian art. The Torah account in Genesis 22 is the main source for the iconography.7 In this account, God told Abraham to bring Isaac as an offering on a mountain in the land of Moriah. “He said, ‘Take your son, your only son, Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the mountains that I shall show you”’ (Gen. 22:2).8 Abraham took Isaac, two young men, and a donkey, and went to the place. Leaving the two men and the donkey behind, Abraham went further with Isaac. Isaac carried the wood that Abraham placed on him. Abraham carried in his hand the fire and the knife for the sacrifice. At the place, Abraham bound Isaac and placed him on the altar on top of the wood. As he stretched his hand and took the knife to slaughter his son, an angel of the Lord called to him from heaven and said not to stretch out his hand against Isaac nor do anything to him. Abraham saw a ram caught in the thicket by its horns and gave it as an offering in place of Isaac.

In addition to the Torah, other Jewish literary sources provide information on the Akedah that fill out the story. They include the Talmud,9 the Targum Onkelos,10 the Targum Pseudo- Jonathan,11 the commentary on Genesis by Rashi,12 the Midrash account of Pirkei De Rabbi Eliezer,13 and Genesis Rabbah.14 Christians were very interested in the stories told in the numerous Jewish sources since they offered additional descriptive information to the narrative of Genesis. These accounts filled in the missing gaps of the biblical stories and provided visual motifs that made their way into early Christian and medieval art.

Motifs of Jewish origin in the depiction of the Akedah include: (1) the image of Isaac with his hands tied in front or in back of his body, on or near the altar; (2) the ram with the tree (‘ilan) rather than the biblical thicket as told in Genesis; (3) the hand of God (bat-kol) pointing downward from the sky issuing from a cloud which does not occur in the Genesis account; (4) the image of Isaac as a young boy; and (5) Abraham with a knife in his hand. Isaac Bound

In Genesis, it is never explained how Abraham bound Isaac, nor is the visual image of the bound Isaac ever described. It only says that Abraham tied up his son, Isaac, and put him on top of the wood on the altar. Early Jewish and Christian portrayals of Isaac show him in a variety of poses lying on the altar, kneeling on the altar, or kneeling alongside the altar, with hands tied in front or back of the body. The Dura Europos painting (pre-244) shows Isaac lying on his side on the altar with his back facing the viewer (fig. 1). His arms are not visible, but most likely his wrists were tied in front of his body.15 In the sixth-century mosaic of the Akedah at the Beth Alpha synagogue (fig. 6), Isaac is floating in the air with his hands tied in front of him.

Many early Christian examples show Isaac bound. On the sarcophagus of Agape and Crescentianus (ca. 325-350), Isaac sits on an altar with hands bound behind his back (fig. 7).

The fresco image of Isaac in Cubiculum C of the Via Latina catacomb in Rome (ca. 320-350) shows Isaac kneeling on one knee alongside the altar with his hands tied behind him (fig. 5). On the sarcophagus of Junius Bassus (ca. 359), Isaac kneels on one knee alongside the altar with his hands tied behind his body (fig. 8). The Great Berlin Pyxis (ca. 400) shows Isaac with hands bound behind his back standing in front of an altar (fig. 9). In the mosaic at San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy (526-547), Isaac kneels on one knee on an altar with hands tied behind his back (fig. 10).

Though the iconography of the bound Isaac varies throughout Jewish and early Christian art, one account from the Midrash, a form of Rabbinic literature that interprets the Hebrew Bible, emphasizes one compelling request from Isaac. According to the Midrash, Isaac asks to be bound tightly so he will not instinctively jerk and possibly injure his father. Isaac said:

Father, I am young and I suspect that my body might move from fear of the knife and I will cause you sorrow, or the slaughter will be invalid and the sacrifice will not rise for you, you should tie me very tight. He sent out his hand to take the knife and tears were flowing from his eyes and his tears were falling into the eyes of Isaac because of the compassion of a father (Genesis Rabbah, 56:8).

These words reflect a person who is very willing to lay down his life for a sacrifice. All images of Isaac in early Jewish and Christian art reveal this. Isaac’s willingness to offer his life for the sacrifice is an important part of the Rosh Hashanah liturgy (of sacrifice and the forgiveness of sins).

The Ram with the Tree

The Book of Genesis states that Abraham saw a ram caught in the thicket by its horns. Early Jewish and most early Christian artworks deviate from the biblical text showing the ram not in the thicket but standing next to a tree or tethered to a tree. The Akedah from Dura Europos shows a ram standing next to a tree (fig. 1). At the Beth Alpha synagogue, the Akedah mosaic depicts a ram tethered to a tree (fig. 6). The ram tethered to a tree also occurs in the badly damaged mosaic of the Akedah in the synagogue at Sepphoris (Weiss, 2000, p. 53), and in the fresco of the sacrifice of Isaac in the Exodus Chapel in the Bagawat necropolis, Egypt, dating from the late third to about the eighth century (Martin, 2006, p. 241). A ram stands next to a tree in the fresco of the sacrifice of Isaac in the catacomb of Callixtus (ca. 200-250, fig. 3) and on the sarcophagus of Junius Bassus (ca. 359, fig. 8). On the Great Berlin Pyxis (ca. 400), the tree is on one side of the altar and the ram is on the other side to the left of Abraham (fig. 9). The fresco in the Via Latina catacomb (fig. 5) shows the ram standing beside an altar without a tree, and the sarcophagus of Agape and Crescentianus shows no ram or tree (fig. 7) probably due to lack of space. In the mosaic of the sacrifice of Isaac at San Vitale, the ram is at the far left standing beneath Abraham’s raised arm with sword while the tree is placed at the far right of the composition (fig. 10). The ram seems to be untethered, ready to be sacrificed in place of Isaac.

According to Rabbinic tradition, the ram of Abraham was created at twilight on Sabbath Eve during the time of creation (Pirkei De Rabbi Eliezer, Avot 5:6). Jewish literary sources do not mention the ram tethered to a tree(Kessler, 2002, p. 91).16 In the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan on Genesis 22, it says Abraham saw a certain ram which had been created between the evenings of the foundation of the world; it was held in the entanglement of a tree by his horns (Targum Pseudo-Jonathan on Genesis. 22:13-14). The Babylonian Talmud says the ram that Abraham sacrificed in place of Isaac was created just before Shabbat (Sabbath) (Pesachim 54a). It seems that the ram was created on Sabbath eve at the beginning of time and was kept in the Garden of Eden, where it grazed beneath the Tree of Life until it was time for its part in the Akedah. The visual formula of a ram standing next to a tree or tethered to one, first depicted in Jewish art of the Akedah and later in Christian images of the sacrifice of Isaac,apparently represents the ram waiting in the Garden of Eden under the Tree of Life until its part in its sacrifice (in place of Isaac), connecting the Akedah to the creation of the world celebrated on Rosh Hashanah.

The Hand of God

The hand of God, whose earliest known appearance is in the synagogue wall painting of the Akedah at Dura Europos (fig. 1) was a symbol of the divine voice of God (the bat kol) (Kessler, 2013, p. 145; Kessler, 2002, p. 90). It is not mentioned in the Bible but occurs in other rabbinic and non-rabbinic literary sources that include Josephus and Philo (Josephus, 1.13; 4.233; Philo, 32, 176; Kessler, 2002, p. 90). In art from the time of Dura Europos through the Middle Ages, whenever the hand appears in art, it is in a narrative context associated with a story from the Bible in which God speaks. At Dura Europos, the hand of God occurs in the Akedah and in several other paintings.17

Though the hand of God emerging from a cloud or the sky is not mentioned in the Old Testament, the cloud of God accompanied by his voice is found throughout. The cloud represents the glory, or the divine presence of God. In the book of Exodus, while the Jews wandered in the desert, the glory cloud is mentioned several times. Some examples include the following, “On Mount Sinai, amidst a cloud, smoke, and the sound of a trumpet, God spoke to Moses delivering the Ten Commandments” (Exod. 19:16-25). In Exodus 24:15-18, Moses went up the mountain and the glory of God, in the form of a cloud, covered it for six days. On the seventh day, God spoke to Moses out of the cloud. The dwelling place of the divine presence of God, frequently shown as a cloud, is known as the Shekinah (the dwelling). Shekinah is not mentioned in Genesis or anywhere in the Old Testament but is found in the Talmud (Talmud Pesachim 117a, Talmud Sanhedrin 39a, Talmud Berachot 6a, Talmud Shabbat 12b, Talmud Tractate Yoma 56b ) and first appears in the Targums.

In Targum Pseudo-Jonathan on Genesis 22, it is written, “On the third day Abraham lifted his eyes and beheld the cloud of glory fuming on the mount, and it was discerned by him afar off…” (Gen. 22:4). “On this mountain Abraham bound Isaac his son, and there the Shekinah of the Lord was revealed unto him” (Gen. 22:14). The Shekinah, the divine presence of God in the form of a pillar of light, rising from the mount where Abraham is leading Isaac, is mentioned in Chapter 31 of Pirke De Rabbi Eliezer in the story of the Akedah.18 A similar story is found in the Midrash.19

The hand of God appears in the mosaic at the Beth Alpha synagogue from the sixth century (fig. 6). In the scene of the sacrifice of Isaac on the sarcophagus of Junius Bassus (ca. 359), the hand of God originally came down and held the knife of Abraham, but both are now broken off (fig. 8).20 On the Great Berlin Pyxis (ca. 400, fig. 9) and in the mosaic of the sacrifice of Isaac at San Vitale (fig. 10), the hand of God appears above Abraham.

The Image of Isaac as a Young Boy

The Old Testament does not state how old Isaac was during the time of the Akedah, but according to Jewish tradition in the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, an Aramaic translation and commentary of the Torah, Isaac was thirty-seven years old (Targum Pseudo-Jonathan 22:20; Scherman, 2000, p. 11, note to Chapter 22).21 This chronology was based on Sarah’s age at ninety, when Isaac was born, to her age at one hundred twenty-seven when she died.22 According to the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, Sarah died from grief upon hearing that Isaac was taken to be slaughtered (Targum Pseudo-Jonathan on Genesis 22:20). Her death occurred immediately following the Akedah that would place Isaac at thirty-seven years of age.

Most images of Isaac in art, whether Jewish or Christian, show him as a young boy. The earliest known portrayal of Isaac in art, seen in the synagogue at Dura Europos dating pre-244 (fig. 1), shows Isaac as a young boy lying on the altar. Images of the sacrifice of Isaac in the Roman catacombs (e.g., catacomb of Priscilla, second half of the third century, fig. 4) and on sarcophagi (e.g., the Mas d’ Aire sarcophagus, ca. 270; the sarcophagus of Marcus Claudianus, ca. 330-340; the sarcophagus of Agape and Crescentianus, ca. 325-350, fig. 7; the sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, ca. 359, fig. 8) all show him as a young boy.

Na’ar is the Hebrew word used for boy in Genesis 22:5: “He (Abraham) said to his servants, ‘stay here with the donkey while I and the boy go over there.”’ The word na’ar occurs in Genesis 22:12 when God tells Abraham not to lay a hand on the boy. Na’ar can mean a young male ranging in age from infancy to adolescence. The word is also used to indicate a man who has yet to be married.

So why the discrepancy between the images of an older Isaac, presented in the traditional rabbinic text, and that of the much younger Isaac, seen in the visual material beginning in the third century? One scholar, Edward Kessler (2013, p. 121), has noted that some early Church Fathers described Isaac as a boy. Origen of Alexandria(ca. 183/184-253/254) portrayed Isaac on the three-day journey as a “child might weigh in his father’s embraces for so many nights, might cling to his breast, might lie in his bosom (Origen, Homily on Genesis 8.4. PG 12, 206-209; Heine, 1982, p. 140).” Eusebius (ca. 260/265- 339/340), bishop of Caesarea, wrote that Genesis 22.3 did not say a lamb, young like Isaac, but a ram, full-grown, like the Lord (Eusebius, Catena no. 1277).

There is a parallel between the attempted sacrifice of Isaac and the attempted sacrifice of Iphigenia from ancient Greek mythology. Both were offered as a sacrifice by their fathers, and both were rescued at the last minute by divine intervention. God saved Isaac at the last moment from the sacrificial knife of his father while on the altar, and the goddess Artemis saved Iphigenia at the last moment from the sacrificial knife of her father while on the altar. A ram (provided by God) was substituted for Isaac at the altar, and a deer was substituted for Iphigenia by Artemis at the altar. Could there have been an earlier pictorial tradition in manuscript illumination of the sacrifice of a young Iphigenia, now lost, that provided the visual formula for a young Isaac at the altar? Whatever the reason for portraying a young Isaac, it continued in most Jewish representations of the Akedah and in most Christian representations of the sacrifice of Isaac that followed. Perhaps Hellenistic culture provided a visual vocabulary that influenced these portrayals of Isaac.

Abraham with the Knife

All images of Abraham in the sacrifice of Isaac story depict him with a knife. This follows what is written in the Bible and the Targums. “Then he reached out his hand and took the knife to slay his son” (Gen. 22:10).

Conclusion

In summary, these are examples of early Jewish iconography of the Akedah that were based on the biblical narrative in Genesis 22:1-19, the Talmud, the Targum Onkelos, the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, the commentary on Genesis by Rashi, the Midrash account of Pirkei De Rabbi Eliezer, and Genesis Rabbah that made their way into the Christian portrayal of the sacrifice of Isaac. Isaac, who volunteered to be bound, led to the name of the event, the Akedah, which means binding. It refers to the marks left on his wrists and ankles discussed in the Midrash. The Tree of Life under which the ram waited until its part in its sacrifice (in place of Isaac) connects the Akedah to the creation of the world celebrated on Rosh Hashanah. Lastly the hand of God issuing from a cloud, the image of a young Isaac on an altar, and Abraham holding a knife first appear in Jewish art at Dura Europos. These notable Jewish contributions went on to influence the Isaac story for centuries making it one of the most celebrated stories in art. More importantly, because of its association with the liturgy of Rosh Hashanah, the Akedah painting in the synagogue at Dura Europos sets the tone of salvation and liturgy iconography that will follow in all later depictions of the binding/sacrifice of Isaac in Jewish and Christian art.

References

Berman, L. A. (1997). The Akedah: The binding of Isaac. Northvale: Jason Aronson Inc.

Etheridge J. W. (2005). The Targums of Onkelos and Jonathan Ben Uzziel on the Pentateuch (Vol. 1). New Jersey: Gorgias Press.

Fine, S. (2007). Jewish art and biblical exegesis in the Greco-Roman world (pp. 25-50). Picturing the Bible. J. Spier, (Ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press.

Gutmann, J. (1987). The sacrifice of Isaac in medieval Jewish art. Artibus et Historiae, 8(16), 67-89.

Gutmann, J. (1988). The dura europos Synagogue paintings and their influence on later Christian and Jewish art. Artibus et Historiae, 9 (17), 25-29.

Gutmann, J. (1992). Revisiting the “binding of Isaac” Mosaic in the Beth-Alpha synagogue. Bulletin of the Asia Institute, 6, 79-85.

Hayward, R. (2010). Targums and the transmission scripture into Judaism and Christianity. Leiden: Brill.

Heine, R. E. (1982). Fathers of the church, origen, homilies on genesis and exodus. Washington D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press.

Josephus. (2018). Antiquities of the Jews (W. Whiston, Trans.). St. Paul, MN: Wilder Publications.

Kessler, E. (2002). The sacrifice of Isaac (the Akedah) in Christian and Jewish tradition: Artistic representations. In M. O’Kane(Ed.), Borders, boundaries and the bible (pp. 74-98). New York: Sheffield Academic Press Ltd.

Kessler, E. (2013). Jews, Christians and muslims in Encounter. London: SCM Press.

Kraeling, C. H. (1956). The synagogue. The excavations at dura Europos: Final report 8.1 (pp. 346-363). New Haven: Yale University Press.

Martin, M. (2006). Observations on the paintings of the Exodus Chapel, Bagawat Necropolis, Kharga Oasis, Egypt. Byzantine Narrative. Papers in Honor of Roger Scott (pp. 233-257). J. Burke (Ed.). Melbourne, Australia: Australian Association for Byzantine Studies.

McNamara, M. (2010). Targum and testament revisited, Aramaic paraphrases of the Hebrew Bible (2 nd). Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

Mortensen, B. (2006). The priesthood in Targum Pseudo-Jonathan: Renewing the Profession. Leiden: Brill.

Neusner, J. (1985). Genesis Rabbah: The Judaic commentary to the book of genesis: A new American translation (Vol. 2). Philo, On Abraham: University of South Florida.

Sawyer, J. F. A. (2012). (Ed.). The Blackwell companion to the Bible and culture. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Scherman, R. N. (2000). The Chumash: The stone edition, The Torah: Haftaros and Five Megillos with a commentary anthologized from the rabbinic writings. Art scroll series. New York: Mesorah Publications, Ltd.

Solomon, N. (2009a). Judaism, a brief insight. New York: Sterling Publishing.

Solomon, N. (2009b). The Talmud: A selection. New York: Penguin Classics.

Spitzer, A. N. (2010). Abraham and Isaac. Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion (Vol. 1). D. A. Leeming, K. W. Madden, and S. Marlan, (Eds.). New York: Springer.

Steinsaltz, A. (2006). The essential talmud. New York: Basic Books.

Sukenik, E. L. (1932). The ancient synagogue of Beth Alpha. Jerusalem: Jerusalem University Press.

Weiss, Z. (2000). The sepphoris synagogue mosaic. Biblical Archaeological Review, 26(5), 48, 50-55, 58-61, 70.

1 Art as decoration was permitted in synagogues if not used for idolatrous purposes. See the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan (on Lev. 26:1); “You shall not make to you idols or images, nor erect for you statues to worship, neither a figured stone shall ye place in your land to bow yourselves toward it. Nevertheless, a pavement sculptured with imagery you may set on the spot of your sanctuary, but not to worship: I am the Lord your God.” Targum Pseudo-Jonathan; Etheridge, 2005. Mosaics and frescoes occur in synagogues at Capernum, En Gedi, Beth Shean, Beth Alpha, and Gaza; Kessler in Sawyer, 2012, p. 128.

2 The figure of Isaac is seen from his back as he lies on his right side on the altar. His hands are most likely tied in front of him.

3 Inscriptions (1a, 1b, 1c) were written in Aramaic, Greek, and Middle Persian; C. Torrey in Kraeling, 1956 = Syr 84, Syr 85.

4 The menorah, described in the Bible, is a seven-lamp Hebrew lampstand of pure gold that was originally set up by Moses in the wilderness and later in the Jerusalem Temple. A lulov (palm branch) was joined with myrtle and willow branches. Together with an etrog (citron fruit), they were held and waved to send out a blessing to all creation during the synagogue service on Sukkot. Sukkot, also known as the Feast of Tabernacles or the Feast of Booths, commemorates the years the Jews spent in the desert on their way to the Promised Land.

5 The original paintings of the assembly room are now in the National Museum in Damascus.

6 Between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries about twenty-seven illustrations are known, mostly from the Franco-German regions (known as Ashkenaz) in medieval Hebrew sources. Three others are known from Spain (known as Sepharach), and one is known from Naples. These are mostly found in manuscripts which include Bibles, festival prayer books called Mahzorim, and private liturgical books (Haggadot) used for the seder (the ceremonial dinner that celebrates the exodus of the Jews from Egypt) at Passover Eve. Many of these show the standard iconography that one associates with the Christian portrayal of the subject. Scholars have noted the interchangeable influence between Christian and Jewish elements throughout the centuries. See Weiss, 2000, pp. 48-61, 70.

7 The Torah is the Hebrew name for the first five books of the Old Testament. It is also known as the Chumash, the Pentateuch, or the Five Books of Moses.

8 Many Muslims believe that it was Ishmael, and not Isaac, who was intended for the sacrifice since Ishmael was the only son for fifteen years until the birth of Isaac. The story of the sacrifice of Abraham’s son is mentioned in the Koran (Sura 37:100-107), but the name of the son is not given. See Spitzer, 2010, p. 1.

9 The Talmud, commonly known as the oral Torah, is the summation of Hebrew oral law and customs from thousands of years. See Solomon, 2009, Judaism, xv; Solomon, 2009, The Talmud; Steinsaltz, 2006. It explains Jewish tradition, religion, culture, and oral law. The oral laws were given to Moses by God on Mount Sinai along with the Ten Commandments and were transmitted orally for centuries. Consisting of an enormous body of information, the Talmud was compiled in writing ca. 200-500 by many Hebrew scholars who lived in Palestine and Babylonia. It has two main parts: (1) the Mishnah, a book of law (halakhah); and (2) the Gemarah, a commentary on the Mishnah. In all, there are sixty-three sections called tractates. The Palestinian Talmud dates ca. 400, and the Babylonian Talmud dates ca. 500.

10 The Targum Onkelos is an Aramaic paraphrase of the Pentateuch that includes translation and commentary. Its authorship has been attributed to Onkelos (ca. 35-120). Etheridge, 2005, viii.

11 The Targum Pseudo-Jonathan (Targum Yonasan) is an Aramaic paraphrase of the Pentateuch that includes translation and commentary initially thought to have been written by Yonasan ben Uziel, a first-century rabbi. However, when scholars realized that the Talmud only mentioned that ben Uziel had translated the Prophets, and was not mentioned translating the Torah, the Targum Jonathan, also known as the Targum Yonatan, came to be known as the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan. Its date is highly debated. Dates range from the late fourth century to 900, though most scholars agree that it was most likely based on earlier works. See McNamara, 2010, pp. 2-3. Hayward, 2010, dates it from the late fourth century to the early fifth century. Mortensen (2006) says it is a late fourth-century work.

12 Rashi was a medieval French rabbi and scholar who lived 1040 to 1105. His commentary on the Pentateuch and the Talmud are considered essential in the study of these works even to this day. Scherman, 2000, p. 1301.

13 Midrash is the name given to the extensive body of Jewish commentaries on the Old Testament that were compiled from the second through the fourteenth centuries. While reading the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh or Old Testament), the Jews realized that there were many gaps in the stories being told. Through examination over the years, the Midrash filled in the missing parts. The word Midrash is based on the Hebrew word meaning “interpretation.” Much of the Midrash appears in the Talmud. The account of Pirkei De Rabbi Eliezer is an aggadic midrashic work on Genesis, part of Exodus, and part of Numbers. It is accredited to Rabbi Eliezer ben Hyrcanus (ca. 80-118) and has fifty-four chapters. Scherman, 2000, p. 1301.

14 Genesis Rabbah is a Midrash comprised of rabbinic interpretations of the Book of Genesis. Much of it dates ca. 330 to 500, with some later additions. See Neusner, 1985.

15 The small figure entering a tent in the background may be Isaac shortly after he was released from the intended sacrifice.

16 There is mention of a tethered ram in a fourth-century Coptic Bible; Sacrorum Bibliorum: Fragmenta Copto-Sahidica, vol. 1, 22.

17 It is seen in the stories of the Akedah of Isaac, Exodus and Moses parting the Red Sea, Moses and the Burning Bush, and Ezekial’s vision of the Valley of the Dry Bones. Of these the Akedah is the only one in which the hand of God is coming down from the sky out of a cloud. The rest show the hand coming down from the sky with no cloud.

18 “On the third day they reached Zophim, and when they reached Zophim, they saw the glory of the Shekinah resting upon the top of the mountain, as it is said: On the third day Abraham lifted up his eyes and saw the place afar off (Gen. 22:4). What did he see? (He saw) a pillar of fire standing from the earth to the heavens. Abraham understood that the lad had been accepted for the perfect burnt offering.”

19 Genesis Rabbah 56:2 on Genesis 22:4. “What did he see? He saw a cloud enveloping the mountain and said, ‘It appears that this is the place where the Holy One, blessed be He, told me to sacrifice my son.’ He then said to him: ‘Isaac, my son, do you see what I see?’ He answered: ‘Yes.’ He said to his two servants: ‘Do you see what I see?’ They answered: ‘No.’ He said: ‘Since you do not see it, stay here with the ass, for you are like the ass.’”

20 Abraham grips the handle of the knife, though the blade is missing.

21 Targum Pseudo-Jonathan to Genesis 22:1 indicates that Isaac was thirty-seven at the time of the Akedah. Josephus (1.13:2) writing ca. 94, says Isaac was twenty-five years old.

22 “Sarah lived one hundred twenty-seven years; this was the length of Sarah’s life (Gen. 23:1).”

Journal of Literature and Art Studies2022年1期

Journal of Literature and Art Studies2022年1期

- Journal of Literature and Art Studies的其它文章

- The Latest Development of Ethical Literary Criticism in the World

- Analyzing Darcy’s Pride and Change from a Naturalistic Point of View

- Barbara Longhi of Ravenna:A Devotional Self-Portrait

- The Aesthetic Reception of Poetry Through Painting:“After Apple-Picking”as an Example

- The Media Fusion and Digital Communication of Traditional Murals—Taking the Exhibition of the Series of Tomb Murals in Shanxi During the Northern Dynasty as an Example

- A Feature Analysis of Oroqen Ethnic Group’s Semiosphere