The Aesthetic Reception of Poetry Through Painting:“After Apple-Picking”as an Example

Hamzeh Ahmad Ali Al-Jarrah,Met’eb Ali Alnwairan

Drawing on reader-response criticism, this article aims at analyzing the aesthetic receptive experience of teaching imagery through painting/drawing. We argue that such an approach helps students transcend the limitations of written words by deconstructing the text and reconstructing the meaning, which, in turn, enriches students’creativity, free-thinking, and ability to describe sensory experiences. Our approach, in this case, is a medium of meta-reflection through which students undergo the aesthetic experience while painting/drawing mediates between the text and students’ unconscious mind. The role of reader-response through painting/drawing is to unravel the relational structures that mark this creative process. To this end, we applied this method to an undergraduate class of poetry at Taibah University, Saudi Arabia. The sample consisted of forty-four undergraduate students, who were asked to re-present Robert Frost’s poem, “After Apple-Picking,” in painting/drawing. To analyze the students’ act of reading, the participants were asked to write reflection letters on how they felt throughout the process of preparing their portraits and, consequently, their replies were used in analyzing their portraits. The study presents a replicable model for application to other genres and literary texts.

Keywords: “After Apple-Picking”, Robert Frost, sensory experience, aesthetics reception, reader-response theory

Introduction

Undergraduate students are always in search of the meaning and the interpretation of literary works. More often than not, they find themselves detached from the assigned works on the reading list. Many of them wait for their instructors to interpret and analyze the literary text. This, in fact, creates a gap between the literary text and the students, on the one hand, and makes the students disavow their role in the teaching-learning process, on the other hand.

In general, at the beginning of each lecture, some instructors of English literature are usually faced with such disconcerting questions about how to motivate students and how to get them actively engaged in generating meaning. To bridge the gap between the literary text and students, the researchers have proposed a new interactive method of teaching based on engaging students in the interpretation and analysis process by adopting an aesthetic stance through implementing Reader-Response theory. This aesthetic stance integrates painting in teaching poetry.

This method addresses students’ sensory experience in order to unravel their subconscious mind through the stream of consciousness. The stream of consciousness is rendered by responding to the imagery and metaphors embedded in the poem. Several types of imagery along with the visual metaphors trigger students’ subconscious minds to produce new meanings. Consequently, the interpretation of the literary text becomes the result of the psychological interaction and reaction to the text through the mediation of his/her past experience and social and cultural background.

Rosenblatt (1982) points out that reading is an interactive process between the reader and the text. The reader in this process gives “‘life” to the text. In this process, there is a two-way transaction that involves the reader interpreting the possible meanings of the text, on the one hand, and the text affecting the reader’s thinking, on the other hand. This is what Rosenblatt calls aesthetic involvement with the text, which enables the learner to establish a free subjective and intrinsically human learning experience. Rosenblatt believes that this tolerant learning atmosphere enables the learner to

Adopt the aesthetic stance with pleasant anticipation, without worry about future demands. [There will be freedom, too, for various kinds of spontaneous nonverbal and verbal expression during the reading. These can be considered intermingled signs of participation in, and reactions to, the evoked story or poem. (Rosenblatt, 1982, p. 275)

Our purpose is to show how the semiotic cues in the text generated by several types of imagery and metaphors arouse students’ emotions and make the students reproduce them in visual images. This teaches students how to think metaphorically. Lakoff and Johnson (2008) reiterate,

We observed that metaphor is one of the most basic mechanisms we have for understanding our experience. This did not jibe with the objectivist view that metaphor is of only peripheral interest in an account of meaning and truth and that it plays at best a marginal role in understanding. We found that metaphor could create new meaning, create similarities, and thereby define a new reality. Such a view has no place in the standard objectivist picture of the world. (p. 211)

The students’ paintings are a matter of re-symbolization of meaning. It reflects students’ subconscious experience by being engaged in interpreting the text, which occurs while reading the poem. Consequently, the students approach the text aesthetically rather than efferently. Rosenblatt (1994) emphasizes that our reading of the literary text should not be efferent but aesthetic and “pays more attention to the sensuous, the affective, the emotive, the qualitative” (p. 934).

Literature Review

In fact, many studies were conducted to analyze the numerous advantages of integrating the arts in the curricula at schools and universities. In a more basic sense, scholars argue that humans are born predisposed to respond to and use rhythmic-modal signals in making meaning. This is a major conclusion of Ellen Dissanayake’s intriguing book Art and Intimacy: How the Arts Began (2012). The book presents an outstanding argument on the significance of the arts in our lives today through an exploration of various topics from anthropology, psychology, and sociology among other disciplines. The book traces the psychological and biological evolution of human artistic practices starting with the mother-infant bonds in prehistoric eras. Dissanayake argues that “the antecedents of the arts—rhythmic-modal experiences—evolved to enable our human way of life in relationship with others” (Dissanayake, 2000, p. 205). In her book, Dissanayake sheds light on the “evolved human needs for finding and making “meaning”—needs for system and story—which are addressed and satisfied by cultures in myriad marvelous and singular ways” (Dissanayake, 2000, p. 74). Interestingly, we argue, these “human needs” are still visible in contemporary classrooms as our students—in the experiment group—showed a strong attitude to make meaning and create a “system and story” from the poem under discussion.

Metaphors in poetry are important to connecting words, images and experiences. Lakoff and Johnson’s Metaphors We Live By (2008) examines the role of metaphor in shaping both language and the mind. The authors see metaphors “as essential to human understanding and as a mechanism for creating new meaning and new realities” in life (Lakoff & Johnson, 2008, p. 196). For Lakoff and Johnson, metaphor can be perceived as a“neural phenomenon” which constitutes the neural mechanism that “recruits sensory-motor inference for use in abstract thought” (Lakoff & Johnson, 2008, p. 275). In a similar sense, the students’ paintings in our experiment group showed that the metaphors of the poem are fundamental for aesthetic understanding since they allow the reader to use what he/she knows about the sensual experiences around us to create innovative perceptions of countless other subjects. This conclusion is aided by Lakoff and Johnson’s view that “metaphor could create new meaning, create similarities, and thereby define a new reality. Such a view has no place in the standard objectivist picture of the world” (Lakoff & Johnson, 2008, p. 211).

In their article “Seeing the Value: Why the Visual Arts Have a Place in the English Language Arts Classroom”, Jordan and Dicicco discuss the benefits of incorporating modern visual arts in the English language class in a way that increases students’ motivation, equips educators with new useful teaching tools, and encourages students to think more critically. Jordan and Dicicco (2012) explain that “these benefits arise when visual arts practices are not viewed as separate from, but integral to English language arts instruction” (p. 28). Similar studies show that integrating visual art in language learning improves students’ motivation and attendance (Caterall & Peppler, 2007), increases the ability for creative thinking (Moga, Burger, Hetland, & Winner, 2000), and supports learners’ ability to produce imagery.

In a very interesting study “‘I Just Need to Draw’: Responding to Literature across Multiple Sign Systems”, Short et al. (2000) investigate how students transform what they understand from their literary readings into creative and meaningful expressions in art, drama, or music. The study sheds light on several experiments that ask students to respond to literature through multiple sign systems. The researchers point out that by integrating multiple sign systems in literature, learners skillfully merge and combine different forms of symbolizing in order to express what they want to convey/say. The researchers point out that by the variety of sign systems proposed for learners, children tend to embrace specific sign systems that they consider more suitable for particular ideas and expressions. The study concluded that “by engaging in transmediation across sign systems, they [the children] were encouraged to think and reflect creatively and to position themselves as meaning makers and inquirers”(Short et al., 2000, p. 170).

Another study that seeks to establish connections between the arts and literature is Smith and Herring’s“Literature Alive: Connecting to Story Through the Arts” (1996). This study seeks to answer typical questions posed by language arts teachers like “How can I create ‘living’ experiences that will support my students to explore the ‘layers’ of meaning in a story? What type of learning activity supports students to build personal‘connections’ with a story?” (Smith & Herring, 1996, p. 102). The researchers argue that the arts can be integrated into the curriculum as means to establish connections between various subject areas. This helps students have the opportunity to interact and participate “through personal connections in learning through reading literature” (Smith & Herring, 1996, p. 114).

Methods and Objectives

In order to elucidate the role of the arts in teaching literature and in applying literary criticism, this research tackles an original empirical teaching experiment undertaken by the researchers to scrutinize the new educational dimensions that result from what can be called aesthetic reception of poetry.

The creative nature of arts opens up new possibilities of free and flexible teaching opportunities. Our main concern is not to give answers or solutions, but to provide a new trajectory in teaching poetry that could contribute to the centuries-long argument over teaching/learning traditions. We believe in the virtues of helping students build personal connections with the text rather than implementing traditional reading comprehension skills. While traditional instructional teaching focuses on analyzing the style, themes, context of a story, etc., a more productive and illuminating approach would help students “live” the story while making authentic connections with it. This, in turn, makes the students penetrate deeper into the text’s devices and techniques throughout the process of generating new meanings and representations of the literary “text.”

Based on our experience in teaching literature in general and poetry in particular, we believe that today’s world, with its “intermediality”, can open new avenues to the intellectual, psychological and social development of learners. What we are trying to achieve in this study, as well as in our classrooms, is to encourage students to transform their responses to poetry into an aesthetic creation of their own. These responses can be presented as another type of artistic expression, i.e. painting and drawing.

The arts with their countless channels of expression are an invaluable means of transferring students’perceptions of the literary work beyond the traditional instructional teaching methods. Through implementing the arts in teaching, students present their own narration of the literary work. Students are encouraged to establish subjective connections, expand the existing interpretations, and reflect on them. Students will be trained to connect with literature using their senses, shifting between the verbal and nonverbal in the process. Through these multiple techniques of the aesthetic reception of poetry, the various layers of understanding and several types of expression will be exposed to the teacher.

There are numerous ways in which teachers can engage students in implementing the arts while studying literature. This will be always connected with the teachers’ creativity, the learning environment, and the available facilities. However, fusing the arts with the learning process raises many questions, too. Such questions could be: With what type of literary texts is this method best used? What do we need to know—as teachers of literature—about visual arts? What are the best practices that can help students get the fruits of fusing literature with the arts? What should students know about other arts? Do they need to be familiarized with any philosophical or aesthetic theories in advance? Such kind of questions is responsible, we believe, for locking most teachers in the traditional instructional learning practices. But it is not always as complicated and challenging as it seems. Therefore, the sample group in this study had no beforehand professional training or aesthetic knowledge related to visual arts. Students were not taught anything about such issues, as one of the purposes of this experiment is to unravel students’ thoughts through the stream of consciousness.

We believe that the first step in implementing the aesthetic reception of the poetry model in English language classrooms stems from the teacher’s strong belief in the arts as a liberating and empowering tool of education. When this fundamental “requirement” has been achieved, teachers would mix different art genres like music, drama, and visual arts with the study of literature. At the same time, teachers need to remind themselves of the fact that the focus of their teaching “experiments” is not art per se, but rather implementing the arts in teaching literature to help students develop their critical thinking skills and provide them with more personal and subjective learning experiences. As zealous supporters of this approach, we believe that by the means of the arts’rich and free expressive powers, students’ aesthetic creativity can be initiated and unleashed.

To maximize the benefits of this approach, the students are required to exchange their portraits, share their ideas with other students, and get acquainted with other possible interpretations and analyses of the poem. In Subjective Criticism, David Bleich emphasizes the process of exchanging ideas in the process of generating knowledge, “Even after a negotiation is completed, though, the final knowledge is only a judgment, whose authority may grow or diminish depending on how the judgment fares in ever-large communities” (Bleich, 1987, p. 151). This process helps students engage in a transcendental experience of reproducing knowledge and meanings. By sitting together and reproducing the poem in painting/drawing, students witness a transcendental process of the rebirth of meaning and practice group therapy. As being engaged in a collective spontaneous process of reading and painting/drawing, students’ spontaneous feelings generated through this process would lead to the purgation of their pent-up emotions and feelings.

We selected Robert Frost’s poem “After Apple-Picking” due to several reasons. This poem is very rich with imagery and metaphors and its length makes it appropriate to be taught in one session/lecture. Moreover, the language of the poem is straightforward and very appropriate to the students’ level in this study, in addition to the fact that Forest’s poems always appear on the Department’s syllabi. Robert Frost’s poems give insights into man’s affinity with nature and man’s relation with the universe, through which students can find the link between language and nature. In fact, our teaching model builds a connection between the language used in the text and nature, as exemplified by the students’ portraits of Frost’s poem.

Taking this into our consideration, we are in search of a student-poet painter who will be able to transcend the limitations of the pages, rediscover the meaning, and, therefore, transcend the limitations of the form. Consequently, our approach is an interdisciplinary one which transcends the limitations imposed by individual artistic forms. This does not mean a rejection of literary forms entirely, but rather an excavation of the meaning through an interdisciplinary approach. The fundamental aim of this teaching experiment is to create a teaching/learning process that invariably involves theorizing about this transcendental experience shared by the instructor and the student.

Discussion and Analysis

“After Apple-Picking”, one of Robert Frost’s most vibrant and rich poems, served as an excellent opportunity to test and investigate the reading approach we promote in this study. The experiment was carried out in the spring of 2020 among English major undergraduate students, aged 18-22 years at Taibah University, Saudi Arabia. Overall, 44 participants were asked to draw/paint their own visual understanding of Frost’s poem. Students were encouraged to reproduce and reconstruct the meaning and produce new possibilities of analyzing the poem to reach a deeper meaning and a higher level of understanding through the painting/drawing of the poem. Although challenging, we were intrigued by students’ remarkable interest and enthusiasm in the experiment as they responded with a good number of creative pieces. In order to keep the argument intact, the researchers grouped students’ works into three major categories: those who went scientific in their representation of the poem, those who went spiritual in reproducing the meaning and those who used meta-reflection in their analysis. Therefore, the researchers chose three representative samples of students’ works.

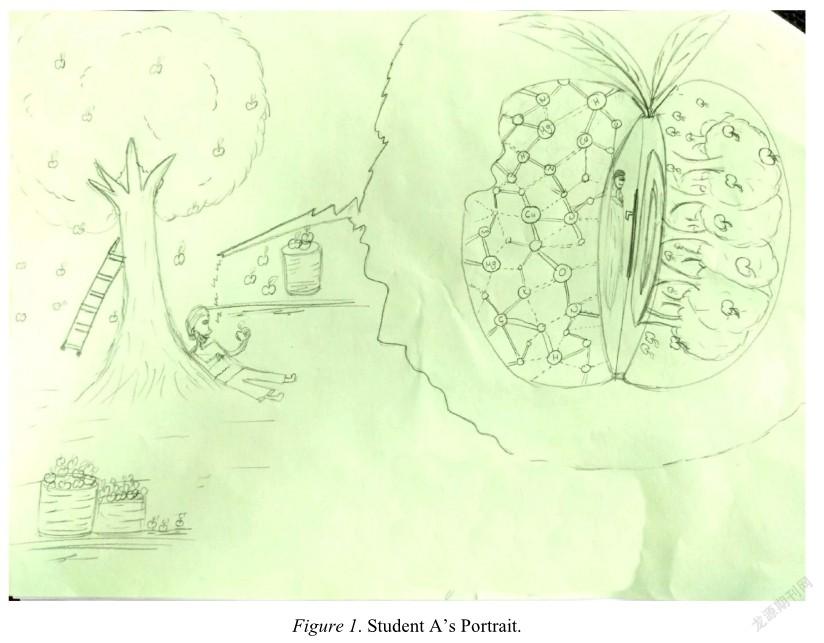

Student A (Figure 1) shows an unconventional understanding of the poem as she departs from traditional interpretations of the poem and goes more scientific. For her, everything revolves around the scent of the falling apples which performs all the magic in the poem. She builds her interpretation of the poem on the speaker’s reference to the effects of the scent of ripe apples and, therefore, the olfactory imagery becomes the new center of the poem to reach a new level of analysis while reproducing a visual representation of the poem: “The scent of apples: I am drowsing off” (Frost, 1971, p. 8). In her portrait, the exhausted apple-picker appears to be lying with his back against a big apple tree. The student makes the olfactory imagery the controlling factor in the poem, which controls other kinds of imagery in the poem such as kinesthetic and gustatory imagery. This helps the student build an organic representation both in the beholder’s mind and in her portrait. In addition to“reconstructing” the general scene of the poem, the student transcends the references to the “magnified apples”(Frost, 1971, p. 18) which “appear and disappear” (Frost, 1971, p. 18) and looks into the chemical ingredients of the apple. In one half of the “magnified” apple appear the chemical ingredients responsible for the “numbness” in the speaker’s mind. All of the chemical elements are connected to each other as they participate, collectively, in the transformation of the speaker’s feelings and attitudes towards life.

The other half of the apple contains an apple orchard loaded with mellow and ripe apples ready for harvesting. It is interesting to see how the student “plays” with the traditional, or rather a natural conception of enlargement and compression as a means to unleash the unconscious mind of the viewer. The magnified apple comprises a large number of apples and apple trees which, in turn, contain more apples in an endless cycle of play. In the dividing part between the two halves of Frost’s apple lies a human being facing a closed door. The door not only separates the two halves of the apple fruit, but forms a barrier between two different worlds, or two different levels of understanding; abstract and concrete. The idea here is about the student’s contemplation of the journey between the sensual and non-sensual in Frost’s poem. The student presents a remarkable attempt to rethink, redefine, and redesign Frost’s poem in a creative way, transcending her initial traditional understanding of the text into a new level that confronts the different possible interpretations of the text.

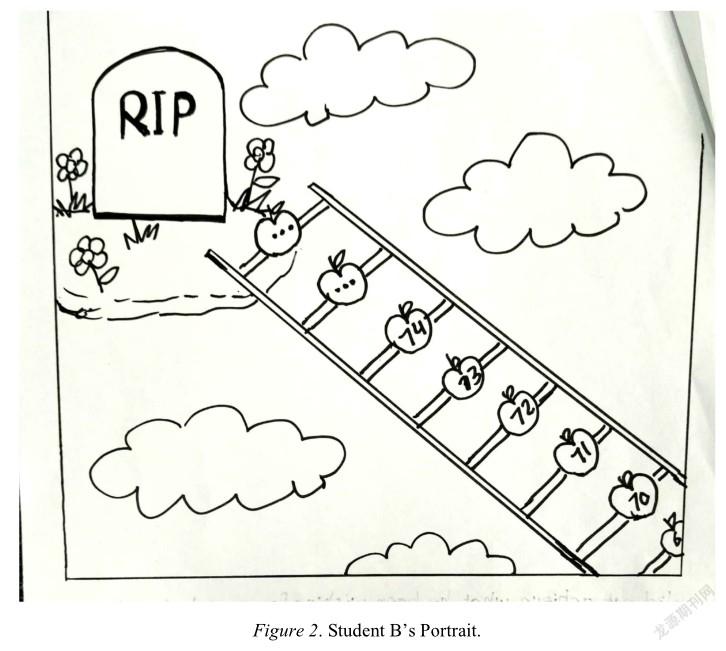

Student B (Figure 2), looks at the poem as a “spiritual’ journey up towards heaven or the afterlife. Here, there is more emphasis on the ladder which serves as a figurative escalator that “drives” the speaker forward in his life. The student’s ladder resembles and symbolizes the Emersonian stairway. The purpose of this allusion is to reach one of the central themes of the poem; the mortality of human beings. In fact, in “Art,” Emerson raises this issue:

‘T is the privilege of Art

Thus to play its cheerful part,

Man on earth to acclimate

And bend the exile to his fate,

And, moulded of one element

With the days and firmament,

Teach him on the seas stairs to climb

And live on even terms with Time ... (Emerson, 1904, p. 278)

Elsewhere, Emerson touches the metaphoric marriage between the sky and the earth in the poem, which creates our book of Fate. He describes the original poet as someone who “wrote without levity and without choice. Every word was carved before his eyes into the earth and sky; the sun and the stars were only letters of the same purport and of no more necessity” (Emerson, 1904, p. 269).

Interestingly, in the portrait by Student B, the apple tree is not visible this time. The apple fruits do not fall from the apple tree into the barrel. Instead, they rise higher and higher in the sky leading to the speaker’s final resting place. It is noteworthy to refer to the student’s bold and independent retold story. She resolves to eliminate some of the major components of Frost’s poem (like the speaker’s character and the apple tree) while reconstructing a totally unique and subjective understanding of the poem. Intentionally or not, the student uses a minimalistic style similar to Ernest Hemingway’s Theory of Omission. In Death in the Afternoon (1952), Hemingway describes his ideas about “theory of omission” or “iceberg theory.” Hemingway thinks if a writer:

Knows enough about what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of the iceberg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water. The writer who omits things because he does not know them only makes hollow places in his writing. (Hemingway, 1932, p. 192)

For Student B, the apple-picking process is another symbol of growing older with the number of apples representing the number of years of the speaker’s life. The more apples the speaker picks, the closer he gets to the end of his/her life. The last two apple fruits are not numbered, communicating the idea that the speaker has not achieved all of his/her plans in life. “After Apple-Picking,” for the student, is a rough voyage filled with opportunities and achievements that people need to experience and encounter. The approach Student B uses shows signs of free-thinking and creativity that is absolutely out of the box. Based on the drawing, the student is able to adapt the available meaning into a more sophisticated level of thinking as she reconstructs the various components of the poem into a new and unconventional human perspective.

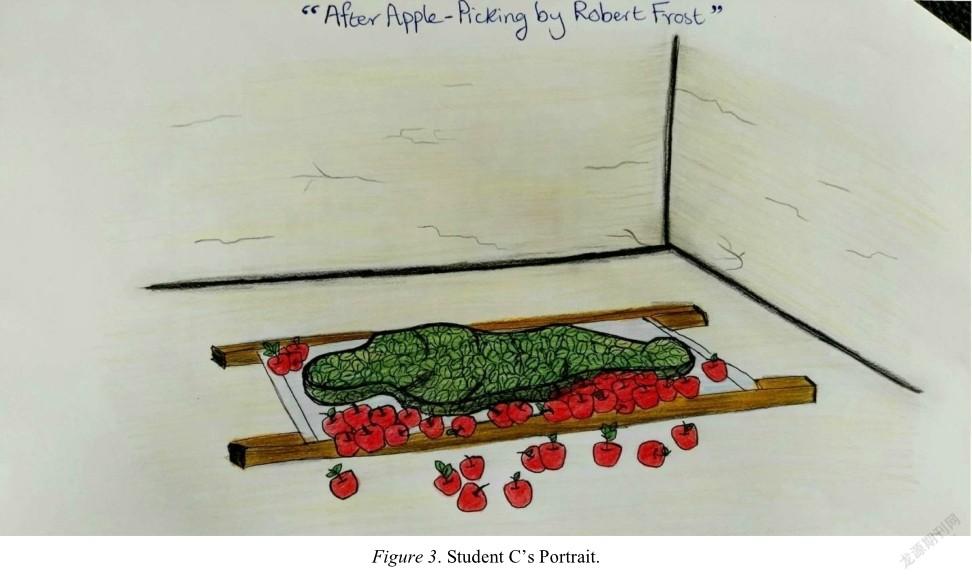

Student C (Figure 3), moves interpretation into a more sophisticated level while deconstructing/reconstructing the major elements of the poem. After analyzing, observing, and reinterpreting the poem as an intellectual task, the student produced a totally innovative version of Frost’s poem. Similar to students A and B, this student uses meta-reflection to enhance free-thinking and to move the interpretation towards new transcendental meanings. As one of the most original students’ works in this study, the painting fuses the major element of the poem into one entity to construct a concentrated vision of the student’s interpretation of the text. Poem elements like ladder, apple tree, apple fruit, sleeping, and dreams are merged to form a new interpretive perspective.

Student C’s painting shows a dead body placed on a ladder and shrouded by apple-tree leaves. According to the student, the funeral is attended only by the apples picked during the deceased’s work in apple-picking. She further said, only our good deeds could help us in the afterlife. It is interesting to see the way in which Student C renounces the traditional way of interpreting the poem. Going in line with this idea, Student C’s painting is no longer confined to the apple orchard boundaries or the natural landscape. The student’s perspective in this painting is rather gloomy and pessimistic as both death and the afterlife prevail in the scene. This sophisticated interpretation of the poem can be viewed as mediation between the text and the student’s unconscious mind. The painting serves as a testimony that the student is able to transcend the limitations of his/her reality through deconstructing and reconstructing the various elements of the text.

Nearly all of the students who undertook this experiment agreed that drawing/painting their personal understanding of the poem sharpened their ability to analyze and interpret Frost’s poem. Students A and B, for instance, highlighted the fruits of meta-reflection in analyzing, observing and re-interpreting literary works. They were able to show the different kinds of imagery in painting which were, for them, something very interesting, though challenging. The experiment enabled them to reconstruct the existing meanings and reproduce new possibilities for analyzing the poem. Most importantly, painting/drawing introduced a new medium to express their feelings towards the poem, towards life, and towards their individual selves, too. For student C, a poem is an artistic piece of art while the portrait serves as a “silent poem.” Each line, expression, or even every single word forms a particular visual image in the reader’s mind. Student C believes that her painting speaks for itself and it, in turn, can be interpreted as a genuine literary/artistic expression of its creator. The experiment, for Student C, enabled her to express thoughts and emotions freely as language, sometimes, is incapable of expressing what lurks deep in our minds.

In general, students’ responses support earlier findings regarding the effects of integrating literature with arts like Harland et al. (2000) who point out that the students from various levels developed their academic performance as a result of their exposure to the arts; Catterall et al., (1999) who explain that there is a positive association between students’ engagement in the arts and their future academic and social performance; and Fiske’s study (1999) which concludes that the arts engage students in multiple skills that improve their abilities. This process, Fiske adds, creates invaluable learning experiences in the classroom. Fiske concludes that the students who are engaged in the arts can achieve remarkable development in their scores (pp. vi-viii).

It is always interesting to see how students find new centers for their paintings. In most cases, they were successful in transcending the limitations of reality to find a new focus that reflects their creative minds. The process of centering and decentering, we believe, adds more to the students’ skills of interpretation and develops their literary expression. Student A, for example, finds a center in the very basic ingredients of an apple fruit. On the other hand, Student B boldly decenters the apple tree and the speaker’s character and replaces them with a new center; the ladder. This detachment from “safe” traditional readings of poetry requires high levels of creativity that we have only “triggered” in our classroom. In the same way, Student C decenters all the major possible “centers” in the poem and fuses them into a new center. Physical items like the ladder, apple tree, and apple fruit are combined with abstract ideas like sleeping, dreaming, and the afterlife to form the new center of the poem/painting. This trend to decenter and recenter, which our students enjoyed greatly, is but one sign of the endless and enormous creative abilities that need to be unleashed in classrooms around the world. As facilitators, teachers of literature (as well as all other fields of knowledge) need to encourage students’ creativity and free-thinking by guiding them to travel beyond the limitations of reality to enable them to voice their ideas and enhance their young creative minds.

One might notice that most students emphasized the spiritual journey of the apple picker, and, therefore, one could claim that it is a result of the students’ religious background. In fact, this is not caused by the students’ cultural background which is religion-oriented, but it is mainly caused by Frost’s religious allusions through fusing “natural world, humankind, poetry, word, and play in a realm of visionary imagination” (Morris, 2010, p. 727), which served as a stimulus for students’ subconscious that results in producing new meanings. Most importantly, through this amalgamation, the poem is able to achieve almost similar psychological reactions and effects on the students. On the other hand, Frost’s poem with its metaphors interacts with students’ latent images of the world through their minds’ eyes to reproduce divine truths about life and death.

Conclusion

Through this experiment, students are connected to the text through their sensory experiences that are triggered by the poem’s imagery and metaphors, shifting between verbal and nonverbal. Each student was able to represent the poem in painting, producing a new possible interpretation of the poem. It is intriguing to observe that each student of the study sample discussed in this paper found a new centre for reconstructing meaning.

Student A focused on the olfactory imagery while reproducing the meaning through her painting. The olfactory imagery controls other types of imagery that appear in the student’s painting. She was more scientific in her analysis as her painting shows. She presents two levels of understanding: the abstract and the concrete. On the other hand, Student B and C were more concerned with the spiritual world that the poem creates in their minds. In Student B’s painting, the visual imagery unleashes the student’s subconscious and, therefore, the student’s painting focuses on the link between the mundane life and the spiritual journey, or the afterlife. Interestingly, Student C’s painting fuses all the major elements of the poem into one entity as the painting mediates between the text and her subconscious.

References

Bleich, D. (1987). Subjective criticism. Taipei: Two Leaves.

Catterall, J., & Peppler, K. (2007). Learning in the visual arts and the worldviews of young children. Cambridge Journal of Education, 37(4), 543-560. DOI:10.1080/03057640701705898

Dissanayake, E., & Ellen, D. (2000). Art and intimacy: How the arts began. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press.

Emerson, R. W. (1904). The complete works of Ralph Waldo Emerson. E. Emerson (Ed.). Boston: Houghton.

Fiske, E. (Ed.). (1999). Champions of change: The impact of the arts on learning. Washington: The Arts Education Partnership.

Frost, R. (1971). Robert frost’s poems. New York: Pocket Books.

Harland, J., Kinder, K., Lord, P., Stott, A., Schagen, I., & MacDonald, J. (2000). Arts education in secondary schools: Effects and effectiveness. Slough: National Foundation for Educational Research.

Hemingway, E. (1952). Death in the afternoon. New York: Scribner.

Jordan, R. M., & DiCicco, M. (2012). Seeing the value: Why the visual arts have a place in the English language arts classroom. Language Arts Journal of Michigan, 28(1), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.9707/2168-149X.1928

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (2008). Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Moga, E., Burger, K., Hetland, L., & Winner, E. (2000). Does studying the arts engender creative thinking? Evidence for near but not far transfer. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 34(3-4), 91-104. https://doi.org/10.2307/3333639

Rosenblatt, L. (1982). The literary transaction: Evocation and response. Theory into Practice, 21(4), 268-277. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1476352

Rosenblatt, L. (1994). The transactional theory of reading and writing. In D. E. Alvermann, N. J. Unrau, & R. Ruddell (Eds.), Theoretical models and processes of reading (6th ed., pp.932-956). Newark: International Reading Association.

Saundra, M. (2010). Twentieth-century American poetry. In S. Petrulionis, L. Walls, & J. Myerson (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Transcendentalism (pp. 719-730). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Short, K. G., Kauffman, G., & Kahn, L. H. (2000). I just need to draw: Responding to literature across multiple sign systems. The Reading Teacher, 54(2), 160-171. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20204892

Smith, J. L., & Herring, J. D. (1996). Literature alive: Connecting to story through the arts. Reading Horizons: A Journal of Literacy and Language Arts, 37(2), Article 1.

Journal of Literature and Art Studies2022年1期

Journal of Literature and Art Studies2022年1期

- Journal of Literature and Art Studies的其它文章

- The Latest Development of Ethical Literary Criticism in the World

- Analyzing Darcy’s Pride and Change from a Naturalistic Point of View

- Barbara Longhi of Ravenna:A Devotional Self-Portrait

- Jewish Sources for Iconography of the Akedah/Sacrifice of Isaac in Art of Late Antiquity

- The Media Fusion and Digital Communication of Traditional Murals—Taking the Exhibition of the Series of Tomb Murals in Shanxi During the Northern Dynasty as an Example

- A Feature Analysis of Oroqen Ethnic Group’s Semiosphere