Codeswitching in East Asian University EFL Classrooms:Reflecting Teachers’ Voices①

The University of Waikato, New Zealand

During the 20th century, it was commonly assumed that the best way to teach English as a foreign language was through the exclusive use of English as the medium of instruction. Although recent publications have challenged this view, many educational policy-makers in schools and universities still tend to to insist on “English only”, and decry the practice of codeswitching between the target language and the first languages of learners and teachers. Findings from a recent volume of case studies clearly show that codeswitching is a common practice across a wide range of university EFL classrooms in Asian contexts. In many cases, this codeswitching may be regarded as a “flexible convergent approach”, where languages are switched more or less spontaneously and at random. Often, however, the teachers reported in Barnard and McLellan (2014) responsibly alternated between languages in a principled and systematic way. This paper presents and discusses observational data and extracts from interviews with teachers on the rationale for codeswitching. Thus codeswitching is both normal and can be pedagogically justifiable. The paper will then suggest how teachers can reflect in-, on- and for-action (Farrell, 2007) by systematically recording, listening to, and analysing their use of language(s) in their own classrooms, using a set of interactional categories (Bowers, 1980). Reflective practitioners may then develop collaborative action research projects (Burns, 1999, 2010) which could empower them to critique and challenge monolingual language-in-education policies.

Keywords: codeswitching, East Asia, universities, teacher beliefs, teacher practice.

Correspondence should be addressed to Professor Roger Barnard, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Gate 1 Knighton Road, Hamilton 3240, New Zealand. Email: rbarnard@waikato.ac.nz

INTRODUCTION

This article uses the following broad definition of code switching:

a change by a speaker (or writer) from one language or language variety to another one. Code switching can take place in a conversation when one speaker uses one language and the other speaker answers in a different language. A person may start speaking one language and then change another in the middle of their speech, or sometimes even in the middle of a sentence (Richards & Schmidt, 2002, p. 81).

The latter form of code switching is sometimes referred to as code mixing which, according to the same authors (2002, p. 80), is “quite common in bilingual or multilingual communities and is often a mark of solidarity”. Despite its frequent and natural use in bilingual communities—and, after all, language teaching classrooms are essentially bilingual communities—code switching is frowned upon by many educational policy-makers in teaching English as a foreign language (EFL). The origins of this attitude lie in the rejection by language teaching theorists in the early 20th century of Grammar-Translation as a valid way of teaching modern languages—even though this approach is still widely used by EFL teachers in many contemporary classrooms. The rejection was most clearly enunciated in a conference organised by the British Council in 1961 at Makarere University in Uganda, where those present enunciated several principles for teaching ESL/EFL, among which were that English is best taught monolingually- and also the best teacher of English is a native speaker of that language (Phillipson, 1992). Since then, it has been widely assumed by many textbook writers, methodologists, and researchers into Second Language Acquisition that English should be taught through English, and that the first language of the learners, and that of many of their teachers, should be kept to a minimum if not altogether prohibited. This principle has been adopted by methodologists and teacher trainers advocating such approaches as the Direct Method, Audiolingualism, the Silent Way and more recently Communicative Language Teaching. Hall and Cook (2012, pp. 274-277) provide a comprehensive review of the origins and development of this monolingual approach to teaching English.

However, the monolingual principle has increasingly come under scrutiny. Atkinson (1987, p.24) contended that “the potential of the mother tongue as a classroom resource is so great that its role merits considerable attention and discussion.” The arguments that he outlined in this article and a later one (Atkinson, 1993) have been reinforced at greater length by other applied linguists. V. Cook argued that “treating the L1 as a classroom resource opens up several ways to use it, such as for teachers to convey meaning, explain grammar, and organise the class and for students to use as part of their collaborative learning and individual strategy use” (2001, p. 402). More recently, Macaro (2009) and Levine (2011) have argued for the ‘optimal’ use (i.e., the best balance) of both English and other languages in order for the language learners to become “truly bilingual and bicultural” (Levine, 2011, p. 172). In his recent book on the subject, G. Cook (2010) has provided detailed arguments for the use of languages other than English on three grounds. Firstly, there is little or no evidence that supports a monolingual position; he points out that very few Second Language Acquisition studies have ever considered whether translation might aid the acquisition of grammar, and “the rightness of monolingual teaching was never scrutinized” (2010, p. 91). Secondly from an educational point of view, “[t]ranslation can answer both societal and individual needs, further personal fulfilment and development, promote positive social values such as cross-cultural understanding, and extend linguistic knowledge.” (2010, p. 91). Thirdly, he reinforces the point made by Atkinson (1987, 1993) and V. Cook (2001) that “translation can help and motivate students in a variety of pedagogical contexts ... (and) is suited to different types of teachers, and different ages and stages of students” (2010, p. xvii). Butzkamm and Caldwell (2009, 13) even insist that the learners’ first language is “the greatest pedagogical resource” that learners bring to foreign language learning. Hall and Cook (2012, p. 273) have taken the issue more broadly, arguing “the monolingual teaching of English has inhibited the development of bilingual and bicultural identities and skills that are actively needed by most learners, both within the English-speaking countries and in the world at large”. These views have to some extent modified the attitude of some methodologists and textbook writers as may be seen, for example, in the way in which the matter has been treated over recent years in the four editions of Harmer’s (2007)ThepracticeofEnglishlanguageteaching.

Despite these criticisms, many policymakers such as those in ministries of education, schools and universities in East Asia (as elsewhere) have maintained the “English only” position in their mandated curricula and textbooks. For example, in 2001, all universities under the control of the Chinese Ministry of Education “were instructed to use English as the main teaching language in the following subjects: information technology, biotechnology, new-material technology, finance, foreign trade, economics and the law (Nunan, 2003, pp. 595-6). At much the same time, about ten of the most famous Chinese universities decided to buy and use almost all of the textbooks being used at MIT, Harvard and Stanford Universities (Liu, 2009). The Vietnamese Ministry of Education instructed universities there to make plans to “use English as a medium in their training programs. Priority should go... to science, economics, business administration, finance and banking” (MOET, 2005; objective 3, output 2). Public universities in Malaysia mandated the use of the English language in Science and related subjects (Mohini, 2008), and the government allowed, indeed encouraged, an increasing number of private universities to introduce EMI programmes, partly to attract international students-from 87,000 in 2010 to “a target of 150,000 by 2015” (Tham, 2013, p. 4). In Hong Kong, English language teachers are urged to use English “in all English lessons and beyond: teachers should teach English through English and encourage learners to interact with one another in English” (Curriculum Development Council, 2004, p. 109, cited in Swain, Kirkpatrick & Cummins, 2011, p. 3). It is to be hoped that such views could be modified not only by arguments such as those outlined above, but also by empirical evidence. A number of studies have investigated first language use in various Asian school settings (e.g., Canh, 2011; Carless, 2008; Dailey-O’Cain & Liebscher, 2009, Forman, 2007, 2008; Hobbs, Matsuo & Payne, 2010; Kang, 2008; Lin, 1996; Littlewood & Yu, 2011; Liu, Ahn, Baek, & Han, 2004; Pennington, 1995; Qian, Tian, & Wang, 2009, Yoshida,etal., 2009). However, relatively few studies have investigated case studies in East Asian tertiary contexts (e.g., Burden, 2000, 2004; Tian & Macaro, 2012; van der Meij & Zhao, 2010).) The findings reported in this paper are intended to be a modest contribution to inform educational practitioners at all levels about what university teachers actually do and believe about code switching in their regular classrooms. It is also hoped that foreign language teachers both in universities and other contexts will collect and analyse empirical evidence from their own classrooms so as to be able to make principled decisions (Macaro, 2009, p. 38) about the use of their students’ first language.

THE PRESENT STUDY

The data which follow were taken from recorded lessons and interviews with a convenience sample of EFL teachers in four Asian University contexts. These extracts were selected from a wider number of specially-commissioned case studies, fully reported in Barnard and McLellan (2014) and the four authors have kindly given their permission to use the data in this article. The language policies in these institutions were either ‘English only’, or else the maximum use of the target language. One or two teachers, all of whom shared the same first language as their students, were observed in EFL settings in China, Japan, Thailand and Vietnam. All the participating teachers were native speakers of the students’ first language; the students in all these examples were non-English majors.

Table 1 Settings and Participants (pseudonyms are used)

The questions which drove the individual case studies were as follows:

1. How often did code switching occur in these lessons?

2. In what ways were languages mixed?

3. For which interactional purposes did the teachers use the students’ first language?

4. What reasons did the teachers give for their use of the learners’ first language?

To address these questions, two approaches to data collection were adopted: firstly, following informed consent, intact (i.e., complete, uninterrupted, normal) lessons taught by the students’ usual teacher were observed and audio-recorded by a researcher—the author of the relevant case study in Barnard and McLellan (2013). In most cases, this observer-researcher was a peer colleague of the participant

teachers; in the Vietnamese setting, the observer was an experienced teacher educator and researcher from another university. After the lesson observations, each researcher calculated the amount of time that L1 and L2 were used, transcribed the codeswitching episodes that occurred in the lessons, and analysed the extent of different levels of code switching, and examined the purposes served by these episodes. Secondly, each teacher was individually interviewed shortly afterwards by the same researcher. Summaries of the interviews were given to the teachers for respondent validation.

OBSERVATIONAL FINDINGS

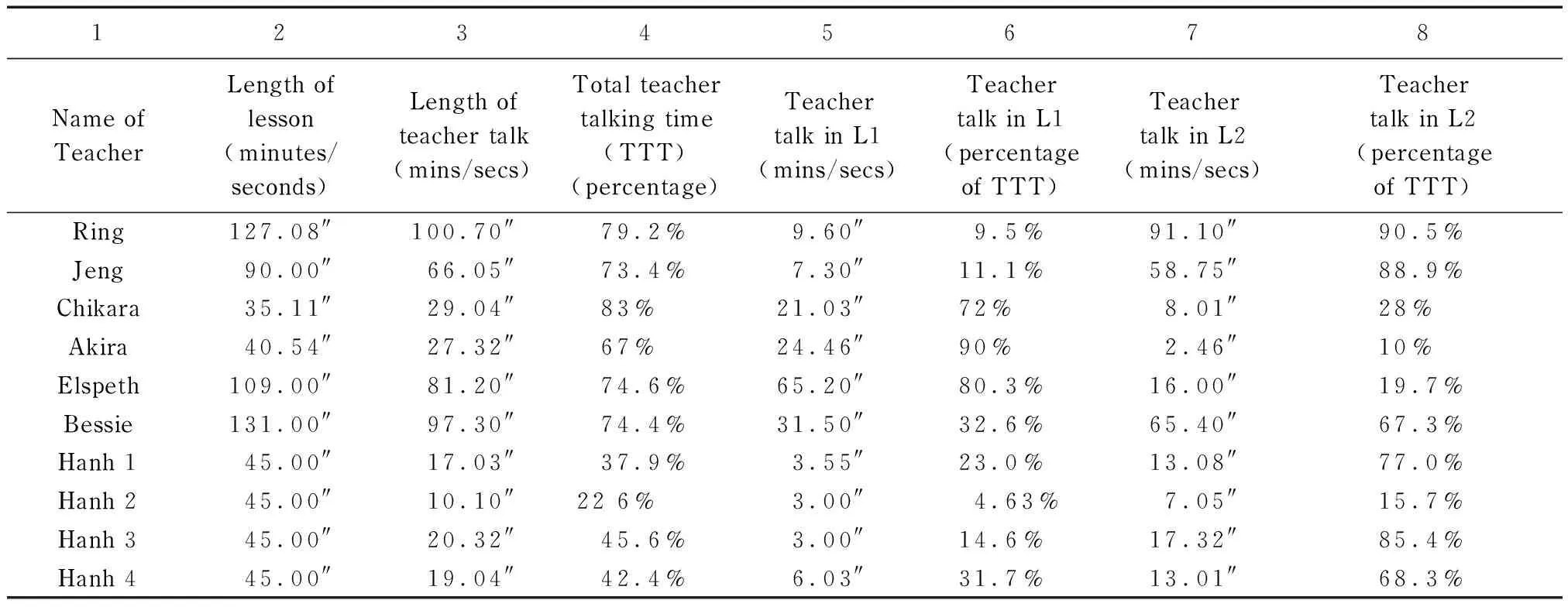

The data collected in regard to the first two questions are provided in Table 2 below.

Table 2 Proportions of Teacher Talk and Code Switching by the Teachers

As can be seen from the table above, there was considerable variation in language use among the teachers. The length of lessons ranged from 35 minutes to well over 2 hours, during which-with the exceptions of the four lessons taught by Hanh in Vietnam-the teacher talked most of the time. (See column 4 above.) In the other six classes, there was much more teacher-talk: an overall average of 75.3%, which is rather higher than indicated in empirical research into classroom interaction elsewhere. Wragg (1999, p. 8) estimated that, on average, teachers spoke for two-thirds of lessons. All the teachers to a greater or lesser extent used code switching: as can be seen from column 6 above, first language use ranging from 4.63% (Hanh) to 90% (Akira), and their reasons for their use will be discussed when the interview data are considered below.

The third question was considered in terms of the extent to which the two languages were mixed or switched, according to the three categories originally devised by Sankoff and Poplack (1981), to which a fourth was added to cover longer code switching utterances in the observed lessons, as indicated in table 3 below.

Table 3 Levels of Code Switching

Note: the use of the word “sentence” is somewhat inappropriate here, as code switching occurred in spoken utterances; however, for the sake of convenience “sentence” is retained throughout this paper.

The fourth question, concerning interactional purposes, was addressed with reference to six categories of classroom interaction originally devised by Bowers (1980). These are provided in table 4 below.

Table 4 Classroom Interactional Categories

Sample data regarding the extent of code switching are presented in table 5 below, which shows that the teachers used their shared first language at different levels for a range of interactional functions.

Table 5 Examples of Extent of Code Mixing /Code Switching According to Speech Categories

Note: plain font=teacher’s original speech;italics=teacher’s use of alternative code; [...]=translation into English of original first language.

From the above table, and other observational data, the following broad statements can be made. Firstly, code switching was most frequently used to explain (a) vocabulary, usually realized by short tags-typically, a translated word, and (b) grammatical forms, realised by inter-sentential code switching and longer terms, such as Ring’s explanation of subject and predicate above. Secondly, both elicitation and directives occurred very frequently; the former was mostly used to check students’ understanding through tags and inter-sentential switching; directives telling students to do a task occurred mostly in inter-sentential switching, and occasionally longer turns such as that of Chikara in Table 5 above. Thirdly, inter-sentential switching and longer terms were used to organise, or structure, learning and also to keep discipline. Finally, evaluation of students’ production was mostly given in English, and where the first language was used it occurred in tags and inter-sentential switching. There was very little sociating going on in most classes and the few teachers who did so tended (as shown above) to use the first language in inter-sentential switching and longer turns. In summary, the above findings indicate that code switching to a greater or lesser extent was a common practice in these EFL settings, and suggest that the code switching practices of university teachers do not substantially differ from those of EFL teachers in primary and secondary school contexts, despite the fact that their own proficiency in English was usually of a high order. Although Walsh (2011, p. 35) argued that “a quantitative view of teacher talking time (TTT) is, to a large extent, redundant”, the significantly higher proportion of TTT displayed in these lessons may be worthy of investigation in other university EFL contexts. The findings relating to the alignment of levels of code switching with the six interactional categories (Bowers, 1980) may indicate that further empirical study in this area would also be useful.

INTERVIEW FINDINGS

It is equally, or perhaps more, important to find out what the teachers believed about their use of the first language, and the following extracts give some indications of this. While there were examples of spontaneous, random and perhaps unnecessary codeswitching, referred to by Garcia (2009) as a “flexible convergent approach”, it was also evident that the teachers made principled decisions about their use of the first language as a means of making language learning more effective.

People’sRepublicofChina

Both teachers switched to Chinese mostly to clarify the meaning and usage of vocabulary in the light of their perceptions of students’ English competence. Jeng explained that “I gave Chinese meanings because the Chinese equivalents correspond well with these English words, and if I used English explanation for these English words I’m afraid that the students would be even more confused.” Likewise, Ring said, “If there is a criterion for me to choose between Chinese and English explanation, it is to judge students’ needs upon their English proficiency level.” She stated in her interview that switching to Chinese was necessary in order to make the point clearer and to save time. Although Ring also switched codes to explain grammatical points (as in table 5 above), Jeng did not use English for this purpose at all, saying that her main focus was on giving information about the content of the lesson, and organizing matters such as assigning homework, for which Mandarin was a more efficient medium.

Japan

Both of these Japanese teachers had a high command of English, but spent a lot of classroom time speaking Japanese. Chikara believed he should use as much English as possible and encourage the students to do likewise. However, he admitted that he actually used Japanese frequently and explained that his students struggled to produce English sentences:

Asking them, sometimes I use English and Japanese, and but for their answers always, I ask them to use English.

His colleague, Akira asserted that students needed a sound foundation in grammar and vocabulary before they could converse in English:

But you see conversation is OK. When you have no solid ground for understanding English, it’s really bad. So before you start teaching, there’s a battle going on how mentally making them turn around to listen to you/or the class, but you know some kids are not interested in listening at all.

Thailand

Although the institutional norm required them to speak as much English as possible, neither of the teachers agreed with the use of only one language, whether English or Thai. However, they showed significant differences in their code switching levels and functions. Elspeth argued:

The Thai language serves as a link to make students better understand what they are learning. Using English only is not a good idea either because students are at different levels. Only some students can cope with English-speaking classes, while the others may not be benefited from this.

She added: “They may roughly understand what the teacher says in English, but Thai makes them understand things more deeply.” Like Elspeth, Bessie sometimes switched codes to explain grammar features or vocabulary items, but she also used Thai to lighten the atmosphere in class:

I codeswitch when students are not so involved in learning. When I speak Thai either to explain or to chitchat, the classroom atmosphere will change. Thai is good for joking. They do not laugh when we make jokes in English.

Vietnam

Hanh’s use of Vietnamese varied from 4.3% to 31.7%. To explain her relatively high use in her first and fourth lessons, she said that it depended on the students’ competence in English:

In my opinion, the students’ reading comprehension would be improved if I explained the important information or difficult sentences in the reading text in Vietnamese.

She added:

In teaching grammar if only English is used, the students just sit quietly with a vague look. They understand nothing. ...I usually switch to Vietnamese to explain grammar or pronunciation because if I use only English the students cannot understand, especially the terminology. If there are words the students don’t know in the rules, I define the words in Vietnamese. If the students don’t understand the grammar point, I explain everything in Vietnamese. If I am correcting the grammar exercises, I use English first and then translate it into Vietnamese.

Like the other teachers reported above, her primary concern was to make the content of the lesson intelligible to her students.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

Every teacher observed in these studies switched to a greater or lesser extent between the target language (English) and the students’ first language, which was also their own. In all cases, although to different extents, code switching occurred at the three levels identified by Sankoff and Poplack (1981): from mixing two languages within one sentence, and switching languages at the clause level, to mixing languages intersententially; there were also often longer turns spoken entirely in the mutual first language. Code switching was seen to serve different interactional functions (Bowers, 1980): presenting, eliciting, organising, directing, evaluating, and sociating, although, as is typical of many EFL classes, very little socialising occurred in either first or target language. Finally, in their interviews, teachers presented various beliefs about the value of code switching in their specific context, but all acknowledged that using the first language facilitated language learning and teaching, especially in regard to their perceptions of the competence and motivation of their students. Evidently, there are many contextual variables to take into account when seeking to evaluate code switching practices, among them: the strictness of an “English only” institutional policy; whether or not the students are English majors; the type and purpose of the lesson; the backwash effect of examinations; the learners’ English language competence; and the professional background of the teachers, including their own competence in the target language. As the observational and interview data show, it is the interrelationship between these factors, rather than any single one, that holds the key.

The findings of the case studies reported in Barnard and McLellan (2014) provide firm empirical support for those applied linguists who have recently called into question the rigid application of “English only” policies in language classrooms. Therefore, the issue to be considered by both educational policy-makers and practitioners is not a question of whether teachers do or do not switch languages in their EFL classes. Rather, it is about “optimal use” (Macaro, 2009). Because each of these examples is a case study, and snapshots taken of only single lessons, no generalisations can be drawn from their findings, either individually or collectively. However, readers in relatable situations may consider that many of the ways that these teachers switch codes, and the explanations they give, do resonate with their own language teaching beliefs and practices.

In particular, it is recommended that language teachers, whether in universities or schools, engage in systematic reflective practice (Schön, 1983; Farrell, 2007) on their language use in classrooms. It is suggested that, every now and then, a teacher audio-record a lesson and afterwards listen to the recording to calculate the total teacher talking time (TTT) during the lesson, and calculate the percentage of the whole lesson-as is done at the start of Table 2 above. This can be done by coding who is talking (T=teacher, Ss=student/s, or S=silence) every five seconds; to get into practice, this could be done every ten seconds. Then the teacher should listen again, and this time code each of his/her utterances as L1, L2 or U (=unintelligible). The teacher may then transcribe the L1 utterances and identify each firstly in terms of Sankoff and Poplack’s (1981) three levels; this would make them aware of the extent of each codeswitched turn. It needs to be emphasized, perhaps, that not all of the teacher’s talk need be transcribed-only the codeswitched episodes. A further analysis could be carried out by relating the data to Bowers’ (1980) interactional categories; again, this will take some practice. Even experts find that the categories are not “water-tight”: some utterances will fall into more than one category, and some will be difficult to fit into any of the categories. However, after such an analysis, it should be possible for the reflective teacher to identify trends in his/her codeswitching practice, and to consider the extent of appropriateness of either the target language or the students’ first language for the particular categories it was used. For example, the teacher may reflect that it might have been better to use the target language for function X, while the first language might have been more appropriate for function Y. After such reflective analyses, and on the basis of empirical data from their actual classroom use, the teacher might then be able to make principled decisions (Macaro, 2009, pp. 38-39) about the “optimal” use of both languages. After all, as McMillan and Rivers (2011) argue, teachers (and learners) are best placed to decide what is appropriate in their own classrooms. Extremely practical examples of how teachers might judiciously use the mother tongue in their classrooms are suggested in Swainetal. (2011). The above suggestions do require time and effort on the part of teachers, but could be undertaken occasionally, perhaps as part of a professional development programme exploring the use of language in the classroom.

An obvious extension to this would be for a group of colleagues in the same, or similar, setting to undertake a collaborative action research project (Burns, 1999; Burns, 1999, 2010). They would follow the same reflective procedures as above, and after a reasonable amount of data from their classes has been collected and analysed, they could discuss the implications and share their reasons for their (inevitably) differential use of first and target languages. They need not agree with each other’s point of view, but it is important that they realise, and appreciate, the range of beliefs and practices about code switching that can occur in the same institutional setting. It would also be useful to triangulate their perspectives with the views of students, as did Fuad Hamied in Barnard and McLellan (2014). They could then collaborate to co-construct plans to optimise language use in their classes, or members may do this individually, based upon a wider understanding of the issues involved. Importantly, they should collectively review these plans after putting them into practice to consider the effectiveness their use of the first and second languages. The action research cycle should continue with further planning, implementation and review in order to enhance student learning, and extend their own understanding of sound language education practice. Importantly, they should disseminate their findings within and beyond their specific context to contribute to greater professional understanding of language use in the EFL classroom.

However, the major action that the team can make, thus empowered with empirical data and shared experience, is to apply pressure on their institutional policy-makers to adopt appropriately context-sensitive regulations or guidance on code switching in language classrooms.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am deeply indebted to Lili Tian, Chamaipak Tayjasanant, Simon Humphries and Le Van Canh, contributors to Barnard and McLellan (2014) for permission to use data from their case studies, and to anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on earlier drafts.

NOTE

1 A preliminary version of this paper was presented at the 47th RELC International Seminar,Multi-LiteraciesinLanguageEducation, Singapore, 16 to 18 April 2012, participation in which was facilitated by a travel grant NZ C1221 from my university.

REFERENCES

Atkinson, D. (1987). The mother tongue in the classroom: A neglected resource?EnglishLanguageTeachingJournal, 4, 241-247.

Atkinson, D. (1993). Teaching in the target language: A problem in the current orthodoxy.LanguageLearningJournal, 8, 2-5.

Barnard, R. & McLellan, J. (Eds.). (2014).CodeswitchinginuniversityEnglish-mediumclasses:Asianperspectives. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Bowers, R. (1980).Verbalbehaviourinthelanguageteachingclassroom. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Reading, England.

Braine, G. (2010).NonnativespeakerEnglishteachers:Research,pedagogy,andprofessionalgrowth. New York: Routledge.

Burden, P. (2000). The use of the students’ mother tongue in monolingual English “conversation” classes at Japanese universities.LanguageTeacher-Kyoto-JALT, 24, 5-10.

Burden, P. (2004). An examination of attitude change towards the use of Japanese in a university English ‘Conversation’ class.RELCJournal, 35, 21-36.

Burns, A. (1999).Collaborativeactionresearchforlanguageteachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Burns, A. (2010).DoingactionresearchinEnglishlanguageteaching:Aguideforpractitioners. New York: Routledge.

Butzkamm, W. & Caldwell, J.A.W. (2009).Thebilingualreform:Aparadigmshiftinforeignlanguageteaching. Tübingen: Narr Studienbücher.

Canh, L. V. (2011).Form-focusedinstruction:AcasestudyofVietnameseteachers’beliefsandpractices. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Waikato, New Zealand.

Carless, D. (2008). Student use of the mother tongue in the task-based classroom.EnglishLangaugeTeachingJournal, 62, 331-338.

Cook, G. (2010).Translationinlanguageteaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cook, V. (2001). Using the first language in the classroom.CanadianModernLanguageReview, 57, 399-423.

Dailey-O’Cain, J. & Liebscher, G. (2009). Teacher and student use of the first language in foreign language classroom interaction: Functions and applications. In M. Turnbull & J. Dailey-O’Cain (Eds.),Firstlanguageuseinsecondandforeignlanguagelearning(pp. 131-144). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Farrell, T.S.C. (2007).Reflectivelanguageteaching:Fromresearchtopractice. London: Continuum.

Forman, R. (2007). Bilingual teaching in the Thai EFL context: One teacher’s practice.TESOLinContext, 16, 20-25.

Forman, R. (2008). Using notions of scaffolding and intertextuality to understand bilingual teaching of English in Thailand.LinguisticsandEducation, 19, 319-332.

Garcia, O. (2009).Bilingualeducationinthe21stcentury:Aglobalperspective. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Hall, G. & Cook, G. (2012). Own-language use in language teaching and learning.LanguageTeaching, 45, 271-308.

Harmer, J. (2007).ThepracticeofEnglishlanguageteaching(4th ed.). Harlow: Pearson Education.

Hobbs, V., Matsuo, A., & Payne, M. (2010). Code-switching in Japanese language classrooms: An exploratory investigation of native vs. non-native speaker teacher practice.LinguisticsandEducation, 21, 44-59.

Kang, D.-M. (2008). The classroom language use of a Korean elementary school EFL teacher: Another look at TETE.System, 36, 214-226.

Kim, E.-Y. (2011). Using translation exercises in the communicative EFL writing classroom.ELTJournal, 65, 154-160.

Levine, G. S. (2011).Codechoiceinthelanguageclassroom. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Lin, A. (1996). Bilingualism or linguistic segregation? Symbolic domination, resistance and code switching in Hong Kong schools.LinguisticsandEducation, 8, 49-84.

Littlewood, W. & Yu, B.-H. (2011). First language and target language in the foreign language classroom.LanguageTeaching, 44, 64-77.

Liu, S. (2009). Globalization, higher education, and the nation state. InProceedingsoftheChinaPostgraduateNetworkConference, 23-24 April, 2009 (pp. 91-100. Manchester, England: Luther King House. http:∥www.bacsuk.org.ik/cpn/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Proceedings20091.pdf#page=91

Liu, D., Ahn, G.S., Baek, K.-S., & Han, N.O. (2004). South Korean High School English teachers’ code switching: Questions and challenges in the drive for maximal use of English in teaching.TESOLQuarterly, 38, 605-638.

Macaro, E. (2001). Analyzing student teachers code-switching in foreign language classrooms: Theories and decision-making.TheModernLanguageJournal, 85, 531-548.

Macaro, E. (2009). Teacher use of code switching in the L2 classroom: Exploring ‘optimal’ use. In M. Turnbull & J. Dailey-O’Cain (Eds.),Firstlanguageuseinsecondandforeignlanguagelearning(pp. 35-49). Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

McMillan, B. & Rivers, D. (2011).The practice of policy: Teacher attitudes to ‘English only’.System, 39, 251-263.

MOET (2005).Vietnamhighereducationrenovationagenda:Period2006-2020. Hanoi: Ministry of Education and Training.

Mohini, M. (2008). Globalisation and its impact on the medium of instruction in higher education in Malaysia.InternationalEducationStudies, 1, 89-94.

Nunan, D. (2003). The impact of English as a global language on educational policies and practices in the Asia Pacific region.TESOLQuarterly, 37, 589-613.

Pennington, M. (1995). Pattern and variation in the use of two languages in the Hong Kong secondary English class.RELCJournal, 26, 89-102.

Phillipson, R. (1992).Linguisticimperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Qian, X., Tian, G., & Wang, Q. (2009). Code switching in the primary EFL classroom in China: Two case studies.System, 37, 719-730.

Sankoff, D., & Poplack, S. (1981). A formal grammar for code-switching.PapersinLinguistics:InternationalJournalofHumanCommunication, 14, 3-45.

Schön, D. (1983).Thereflectivepractitioner. New York: Basic Books.

Swain, M., Kirkpatrick, A., & Cummins, J. (2011).Howtohaveaguilt-freelifeusingCantoneseintheEnglishclass:AhandbookfortheEnglishlanguageteacherinHongKong. Hong Kong: Research Centre into Language Acquisition and Education in Multilingual Societies, Hong Kong Institute of Education.

Tham, S. Y. (2013). From the movement of Itinerant Scholars to a strategic process. In S. Y. Tham (Ed.),InternationalizinghighereducationinMalaysia:Understanding,practices. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Tian, L. & Macaro, E. (2012). Comparing the effect of teacher codeswitching with English-only explanations on the vocabulary acquisition of Chinese university students: A Lexical Focus-on-Form study.LanguageTeachingResearch, 16, 361-385.

van der Meij, H. & Zhao, X. (2010). Code switching in English courses in Chinese universities.TheModernLanguageJournal, 94, 396-411.

Walsh, S. (2011).Exploringclassroomdiscourse:Languageinaction. London: Routledge.

Wragg, E. C. (1999).Anintroductiontoclassroomobservation(2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Yoshida, Y., Imai, H., Nakata, Y., Tajino, A., Takeuchi, O., &. Tamai, K. (Eds.). (2009).Researchinglanguageteachingandlearning:Anintegrationofpracticeandtheory. Oxford: Peter Lang.

- 当代外语研究的其它文章

- Learning Mandarin in Later Life: Can Old Dogs Learn New Tricks?①

- Toward a Theoretical Framework for Researching Second Language Production

- Modality, Vocabulary Size and Question Type asMediators of Listening Comprehension Skill

- Making a Commitment to Strategic-Reader Training

- Metacognition Theory and Research in Second Language Listening and Reading: A Comparative Critical Review

- Thinking Metacognitively about Metacognition in Second and Foreign Language Learning, Teaching, and Research:Toward a Dynamic Metacognitive Systems Perspective