东盟互联互通与中国的“一带一路”

□文/Lucio Blanco Pitlo III

东盟互联互通与中国的“一带一路”

□文/Lucio Blanco Pitlo III

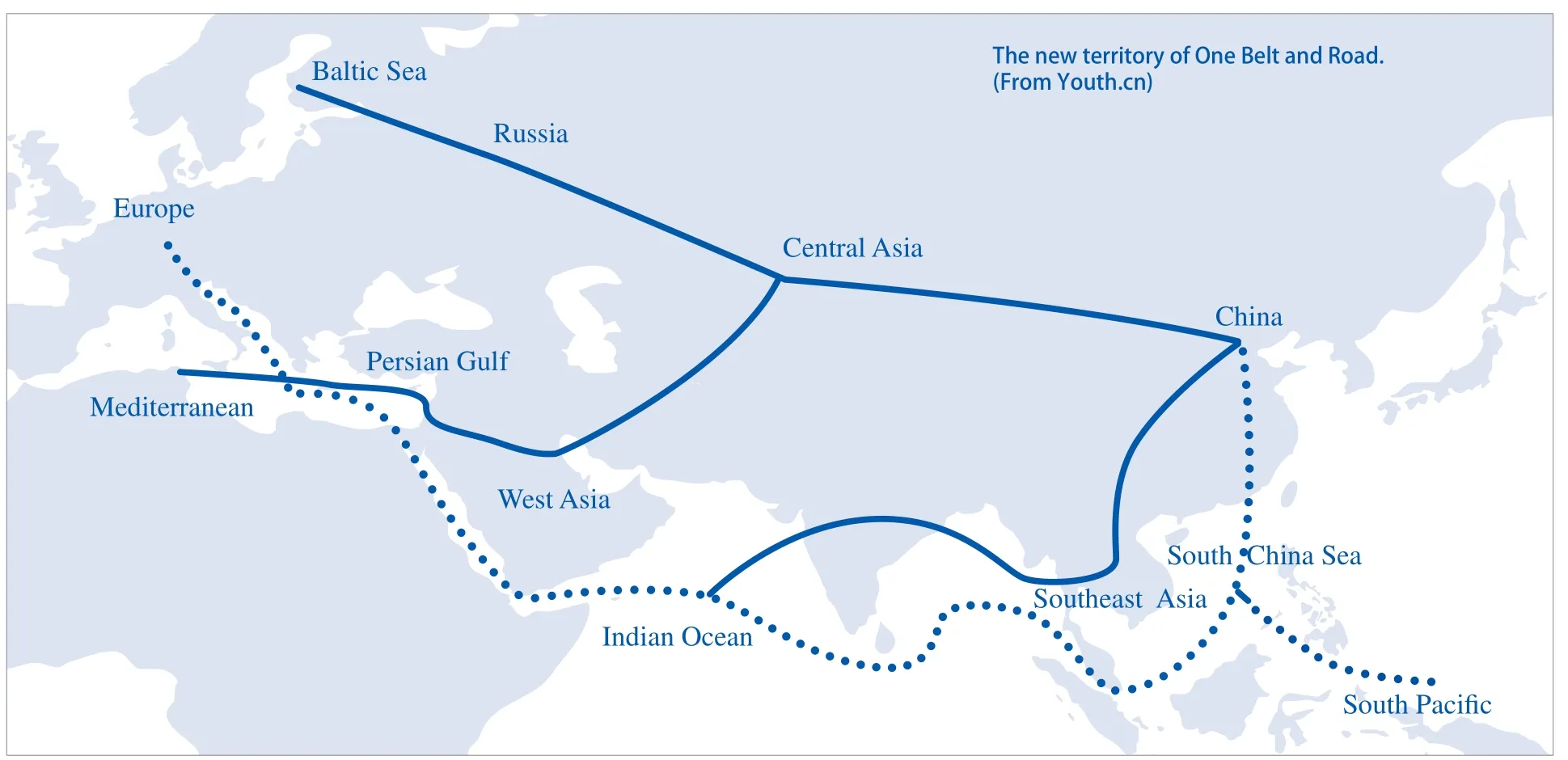

《东盟互联互通计划总体规划》与中国的“一带一路”倡议有着惊人的相似点。两者都把交通互联互通当成是紧密联系各成员国,促进贸易、投资、旅游和人文领域交流的手段。基于这样的共同愿景来探讨两者如何互补、以及可能存在哪些问题是非常有意思的。

通过扩大投资与政府开发援助(ODA)来支持基础设施项目是赢得周边发展中国家支持和友好的方法之一。从这个角度来看,两者的利益趋同十分明显。然而,尽管东盟和中国共同致力于交通互联互通,东盟互联互通计划与中国的丝绸之路相容性到底有多大还有待进一步观察。

近来,中国加大对东盟互联互通计划的援助,这是一个积极的信号。鉴于《东盟互联互通计划总体规划》的执行需要很高的成本,任何捐助和资金支持都是受欢迎的。亚洲发展银行和日本政府开发援助已经参与到《东盟互联互通计划总体规划》中来了,但仍有很大的空间留给亚投行、丝路基金以及中国政府开发援助。中国在港口、码头、高铁等基础设施项目方面已经建立了很高的声誉,可以提供相关技术和经验来支持东盟的计划。东盟互联互通计划也提供机会给中国的基建企业,与东盟当地的企业合作,参与公私合作事业。这是一种吸引私营企业投资公共基础设施项目的新兴模式。

中国与东盟在《东盟互联互通计划总体规划》方面的合作势头持续增长。例如,在东盟地区,长达7000公里的新加坡—昆明铁路连接与东盟互联互通计划的趋同性越来越明显。最近,泰国与中国达成该铁路泰国段的建设项目,这对该铁路的建设将起到极大的推动作用。然而,尽管东南亚大陆上的合作正在加速进行,中国对东盟互联互通计划另外一个组成部分——海上互联互通的支持还不是很明显。2013年3月的一份报告确定了东盟滚装船网络的多条航线,其中三条被确定为2015年的重点实施航线:杜迈(印度尼西亚)—马六甲(马来西亚)航线;巴拉望(印度尼西亚)—槟城(马来西亚)—普吉岛(泰国)航线;达沃/桑托斯将军城(菲律宾)—比通(印度尼西亚)航线。其他航线,如穆阿拉港(文莱)—纳闽岛(马来西亚)—布鲁克斯波因特(巴拉望)航线和穆阿拉港—三宝颜(菲律宾)航线也得以确认。但是,这些次要航线的建设受到了基础设施和机构管理等方面的限制。报告同时还指出了亟待解决的一些问题,如滚装码头无法使用,以及港口与内陆地区需要一个有效的公路体系来连接。这就为中国政府开发援助或是中国企业投资提供了一个新的领域。

近年来,中国加大了在东盟基础设施领域的投资。中国远洋运输集团(COSCO)是世界最大的海运物流公司之一,持有中远新加坡港务局码头有限公司49%的股份。而广西北部湾国际港务集团则持有关丹港口财团38%的股份,拥有管理、经营马来西亚关丹港30年的特许权。同时,中国还投资印度尼西亚基础设施建设,利用其石油、天然气、煤炭以及矿产等自然资源。尽管如此,不同于中国在东南亚大陆的基础设施投资,中国在东盟海岛国家的基础设施投资与东盟滚装船网络没有趋同性。

这可以从几个方面来解释。首先,中国和东盟滚装船网络之间没有直接的联系。昆明—新加坡铁路把昆明与东盟港口直接连接起来,而东盟管装船网络与中国大多数港口相隔太远,很难形成连接。尽管如此,从经济立场上讲,东盟滚装船网络或许对中国并不重要,但作为《东盟互联互通计划总体规划》的一部分,它提供给中国展示其周边外交政策的机会。同样,从能源安全优势角度讲,从非洲和中东驶往东北亚(包括中国)的大型运邮轮可能会选择途径东盟东部增长区海域(龙目岛或望加锡海峡—苏禄海和民都洛海峡——中国南海),而非马六甲海峡。

此外,东盟海岛国家赋予海洋经济和国家利益更高的意义。菲律宾通过共和国水上高速线路来加强岛屿之间的互联互通。印尼提出“全球海洋支点”计划,强调国内各港口以及与东盟主要港口互联互通的重要性。因此,中国支持东盟滚装船网络可以赢得东盟海岛国家以及整个东盟的认可。对《东盟互联互通计划总体规划》和东盟滚装船网络的支持将为中国赢得投资以及邻国的友好,并证明政治上的原则性分歧不会妨碍基础设施领域的合作与发展。

马金羽编译来源: 外交学者网站

(作者系菲律宾中国研究协会研究员)

ASEAN Connectivity and China's "One Belt,One Road"

By Lucio Blanco Pitlo III

T he ASEAN Master Plan for Connectivity (AMPC) and China’s “One Belt,One Road”initiative share striking similarities and parallels.Both envisage transport connectivity as a way to bring member or participating countries closer to one another,facilitating better access for trade,investment,tourism and people-to-people exchanges.Like the “One Belt,One Road” project,AMPC calls for a system of roads and railways to link contiguous Southeast Asian countries with one another,as well as a system of ports for RoRo (roll-on roll-off) vessels and short sea shipping to link insular Southeast Asian countries with one another as well as with mainland Southeast Asia.Given this shared vision,it is interesting to consider how the two could complement one another and what issues could stand in the way.

China has since 2009 been ASEAN’s biggest trading partner and ASEAN has been China’s third largest trading partner since 2011.Trends indicate that twoway trade will only increase further in the coming years.In 2015 alone,it is expected to hit $500 billion.And since seamless transportation infrastructure can better spur trade,plans to enhance connectivity between the two sides are mutually benefi cial.China also puts great emphasis on neighborhood diplomacy,and extending investments and offi cial development assistance (ODA) to fi nance infrastructure projects is one way of winning the support and goodwill of neighboring developing countries.From this perspective,then,the convergence of interests is very apparent.However,while ASEAN and China shared an aspiration of enhancing transport connectivity,it remains to be seen how compatible AMPC and China’s Silk Road project really are.

AMPC is apparently more mature and is at a relatively advanced stage,having been the product of several highlevel discussions and technical working group meetings since 2009.In contrast,the Maritime Silk Road (MSR) was only officially announced in 2013.As such,while many of the key pieces of AMPC had already been laid out,much of MSR’s details remain sketchy and China still has to engage potential partners.China had recently stepped up its efforts to provide assistance in executing ASEAN’s connectivity plan and this is a positive sign.Given the high costs involved in executing AMPC,donors and financial assistance should be welcomed.The Asian Development Bank and Japanese ODA are already engaged in AMPC,but there is still ample scope for the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB),the Silk Road Fund,as well as Chinese ODA.China has developed an impressive reputation in infrastructure projects such as ports,terminals and high-speed trains,and can offer such technology and expertise to support ASEAN’s plan.AMPC may also present opportunities for Chinese companies engaged in infrastructure work to partner with their local ASEAN counterparts in public-private partnership undertakings,an emerging mode for attracting private sector investment in public infrastructure projects.

Indeed,it can be said that momentum for China-ASEAN cooperation in realizing the AMPC is growing.On mainland Southeast Asia,for instance,the convergence of the 7,000 km-Singapore-Kunming Rail Link (SKRL) with ASEAN’s railway connectivity plans is becoming apparent; the recent deal between Thailand and China to construct the Thai section of the route may give this a big boost.If completed,the SKRL will link Kunming,the capital of China’s southwest Yunnan province,with all the capitals of mainland ASEAN countries (except Malaysia,since the line will bypass Kuala Lumpur on its way to Singapore).However,while cooperation on mainland Southeast Asia is picking up steam,Chinese support for the other component of the plan – maritime connectivity – is not yet in evidence.A March 2013 report identified several routes for the ASEAN RORO network (ARN),three of which were designated as priority routes for implementation in 2015:1) Dumai (Indonesia)-Malacca (Malaysia); 2) Belawan (Indonesia)-Penang (Malaysia)-Phuket (Thailand) and; 3) Davao/General Santos (Philippines)-Bitung (Indonesia).Otherroutes were also identified,such as Muara (Brunei)-Labuan (Malaysia)-Brooke’s Point (Palawan) and Muara-Zamboanga (Philippines),but these secondary routes were hampered by such constraints as infrastructure and institutional arrangements.The report cited the unavailability of capable RoRo terminals and the need for a good road system to link ports with hinterland areas as among the issues that need to be addressed.This presents a new frontier for Chinese ODA or investments by Chinese enterprises.In addition,China also has an extensive experience in RoRo and short sea shipping with neighbors Japan and Korea and these lessons and best practices could be shared with appreciative maritime ASEAN states.

In recent years,China had upped the ante in its investments in ASEAN’s infrastructure sector.State-owned COSCO,one of the world’s largest shipping and logistics company,has a 49 percent stake in the COSCO-PSA terminal in Singapore.Beibu Gulf Holding (Hong Kong) Co.Ltd has a 38 percent equity share in a consortium that received a 30-year concession to manage,operate and develop Kuantan Port in Malaysia.This Port is poised to serve as a catalyst for the Malaysia-China Kuantan Industrial Park.China has also been investing in Indonesian infrastructure to facilitate access to the latter’s natural resources,such as oil and gas,coal,and mines.However,unlike in peninsular ASEAN,the patterns of Chinese infrastructure investments in maritime ASEAN states do not suggest convergence with the ARN.

Several factors can explain this.One is the absence of a direct link between China and the ARN.Unlike the rail connection in mainland ASEAN that could provide a landlocked Kunming direct access to an ASEAN port through SKRL,the ARN is too distant from most Chinese ports to facilitate a link.However,while the ARN may have marginal importance to China from an economic standpoint,being part and parcel of AMPC turns it into an opportunity for China to showcase its neighborhood diplomacy.Likewise,from an energy security vantage point,very large crude carriers from Africa and the Middle East bound for Northeast Asia (including China) may pass by BIMP-EAGA waters (through Lombok or Makassar Straits proceeding to the Sulu Sea and Mindoro Strait out to South China Sea) as an alternative to Malacca Strait.

Moreover,maritime ASEAN states are already according greater significance to their maritime economies and national interests.The Philippines had been promoting its Strong Republic Nautical Highway to enhance inter-island connectivity.Indonesia recently unveiled its Maritime Axis/Maritime Fulcrum doctrine which stresses,among other things,the importance of port connectivity not only within the country but also with other major ASEAN harbors.Thus,for China,support for the ARN could win it recognition from individual maritime ASEAN states as well as from ASEAN generally.

Support for AMPC as a whole and the ARN in particular will enable China to win not only investments,but also the goodwill of its neighbors.It may even show that principled disagreement on political issues do not constitute a hurdle to pursuing practical cooperation in infrastructure development.

Lucio Blanco Pitlo III is a member of the Philippine Association for China Studies (PACS).

- 中国-东盟博览(政经版)的其它文章

- 汽车

- nformation

- 农业

- 旅游

- 马新高铁迟迟未上马的17年

- 金融