Traumatic brain injury and palliative care: a retrospective analysis of 49 patients receiving palliative care during 2013–2016 in Turkey

Kadriye Kahveci, Metin Dinçer, Cihan Doger, Ayse Karhan Yaricı

1 Department of Anesthesiology and Reanimation, Ankara Ulus State Hospital, Ankara, Turkey

2 Health Institutions Management, Yıldırım Beyazıt University, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ankara, Turkey

3 Ankara Ulus State Hospital, Ankara, Turkey

4 Department of Anesthesiology and Reanimation, Ankara Ataturk Training and Research Hospital, Ankara, Turkey

Traumatic brain injury and palliative care: a retrospective analysis of 49 patients receiving palliative care during 2013–2016 in Turkey

Kadriye Kahveci1,*, Metin Dinçer2,3, Cihan Doger4, Ayse Karhan Yaricı1

1 Department of Anesthesiology and Reanimation, Ankara Ulus State Hospital, Ankara, Turkey

2 Health Institutions Management, Yıldırım Beyazıt University, Faculty of Health Sciences, Ankara, Turkey

3 Ankara Ulus State Hospital, Ankara, Turkey

4 Department of Anesthesiology and Reanimation, Ankara Ataturk Training and Research Hospital, Ankara, Turkey

How to cite this article:Kahveci K, Dinçer M, Doger C, Yaricı AK (2017) Traumatic brain injury and palliative care: a retrospective analysis of 49 patients receiving palliative care during 2013–2016 in Turkey. Neural Regen Res 12(1):77-83.

Open access statement:is is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non-commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI), which is seen more in young adults, a ff ects both patients and their families. The need for palliative care in TBI and the limits of the care requirement are not clear. The aim of this study was to investigate the length of stay in the palliative care center (PCC), Turkey, the status of patients at discharge, and the need for palliative care in patients with TBI.e medical records of 49 patients with TBI receiving palliative care in PCC during 2013–2016 were retrospectively collected, including age and gender of patients, the length of stay in PCC, the cause of TBI, diagnosis, Glasgow Coma Scale score, Glas gow Outcome Scale score, Karnofsky Performance Status score, mobilization status, nutrition route (oral, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy), pressure ulcers, and discharge status.ese patients were aged 45.4 ± 20.2 years.e median length of stay in the PCC was 34.0 days.ese included TBI patients had a Glasg ow Coma Scale score ≤ 8, were not mobilized, received tracheostomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastros‐tomy nutrition, and had pressure ulcers. No di ff erence was found between those who were discharged to their home or other places (rehabilitation centre, intensive care unit and death) in respect of mobilization, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, tracheostomy and pressure ulcers. TBI patients who were followed up in PCC were determined to be relatively young patients (45.4 ± 20.2 years) with mobilization and nutri‐tion problems and pressure ulcer formation. As TBI patients have complex health conditions that require palliative care from the time of admittance to intensive care unit, provision of palliative care services should be integrated with clinical applications.

nerve regeneration; trauma; palliative care; brain injury; retrospective study; neural regeneration

Accepted: 2016-12-05

Introduction

Traumatic injuries have high morbidity and mortality rates and they can also cause disability (Garcia‐Altes et al., 2012). Although traumatic brain injury (TBI) is seen more in young adults in economically developed countries, it may also be a cause of disability or death in children (Hukkelhoven et al., 2003; Jagnoor and Cameron, 2014; Godbolt et al., 2015). TBI is one of the most signi fi cant causes of long‐term disability throughout the world, primarily in industrialized, developed countries, and it is not only a medical problem but also a public health problem. However, its global incidence re‐mains unknown (Narayan et al., 2002; Corrigan et al., 2010; Humphreys et al., 2013). Surviving TBI patients experience a significant degree of cognitive and physical problems which disturb the establishment of direct communication (Nichol et al., 2011). For those who survive, TBI gives rise to various social and community negative e ff ects (Selassie et al., 2008).e high costs incurred by TBI during the critical period and following acute care can have devastating results for the patient and their family (Hall et al., 2015). Together with the high costs of care, there is also a severe economic burden of TBI due to the loss of productivity (Narayan et al., 2002; Corrigan et al., 2010; Garcia‐Altes et al., 2012). For all these reasons, TBI is a signi fi cant health and socio‐economic problem throughout the world in general.

Patients admitted to the neurological and neurosurgical intensive care unit (ICU) are at a high risk of mortality and because of severe physical and cognitive problems, they are unable to participate in the decision‐making of their own treatment (Creutzfeldt et al., 2015).e increasing severity of illness in surviving TBI patients increases the need for institutional care or care in rehabilitation centers (McGarry et al., 2002). TBI does not just a ff ect the individual who has suffered the trauma, but also deeply affects the caregivers and the community as a whole (Nichol et al., 2011). Al‐though patients and their families have a high requirement for palliative care (PC), there is insufficient knowledge on the best means of administering this care, the frequency andmanner (Creutzfeldt et al., 2015).

The evaluation of PC as a human right renders PC both as a privilege and separated from other healthcare services.ere is a very limited amount of data, even almost negligi‐ble, regarding PC needs in patients with head trauma.us, how PC can be integrated into the care process in the treat‐ment of TBI has become a very important topic.e aim of this study was to investigate PC requirement, hospitalization period, and discharge status of TBI patients in the palliative care center (PCC), Turkey. This retrospective study is im‐portant as the fi rst study in this fi eld in Turkey.

Subjects and Methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by Ankara Numune Training and Research Hospital Ethics Committee (approval No. 11.11.2015/E‐15‐654).

Patients

Measurements

Medical records comprise the information including the age and gender of patients, the length of stay (LOS) in PCC, the cause of TBI, diagnosis, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score, Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) score, Karnofsky Perfor‐mance Status (KPS) score, mobilization status, nutrition routes (oral, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG)), tracheostomy), pressure ulcers (PU) and discharge status (home, rehabilitation centre, intensive care unit, death).

Following TBI, in addition to the use of scales evaluating disability and functionality, GOS is generally used for evalu‐ation of quality of life (Nichol et al., 2011).e KPS is a scale consisting of 11 grades progressing from 0 to 100 points with increments of 10 points according to the performance status, where 0 points = death and 100 points = normal status with no complications or findings of disease (Buccheri et al., 1996).e KPS measures the health status in three areas of activity, work and ability for self‐care and can be used by any healthcare personnel as a rapid assessment of general func‐tion and status (Abernethy et al., 2005). In this study, analy‐sis was made by grouping GCS, GOS and KPS. Patients were divided into three groups as severe GCS (GCS score: 3–8), moderate GCS (GCS score: 9–12) and mild GCS (GCS score: 13–15) (Jagnoor and Cameron, 2014); poor GOS (death and vegetative state), moderate GOS (severe disability) and good GOS (moderate disability and full recovery); severe KPS (KPS score: 0–30), moderate KPS (KPS score: 40–60), and mild KPS (KPS score: 70–100).

In addition, the patients were also grouped according to gender, mobilization status, oral nutrition, PEG, tracheosto‐my, the presence of PU, and discharge status. All the groups formed were compared in respect of age, LOS in PCC, GCS, GOS and KPS scores.

Statistical analysis

able 1 Clinical characteristics ofBI patients subjected to palliative care

able 1 Clinical characteristics ofBI patients subjected to palliative care

*Values are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. **Values are presented asn(%). *** Values are presented as median (25th–75thpercentile). GCS: Glasgow Coma Score; GOS: Glasgow Outcome Scale; KPS: Karnofsky Performance Status; PEG: Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy.

Variable Age (years)*45.4±20.2 KPS**Gender (males/females)**35/14(71.4/28.6) 0 Points 0 LOS in PCC (days)***34(14—105) 10 Points 8(16.3) Cause of trauma**20 Points 11(22.4) Tra ffi c accident — (outside the vehicle) 12(24.5) 30 Points 7(14.3) Tra ffi c accident — (inside the vehicle) 20(40.8) 40 Points 12(24.6) Others 17(34.7) 50 Points 4(8.2) Fall 7(14.3) 60 Points 1(2) Fall from height 8(16.3) 70 Points 3(6.1) Assault 2(4.1) 80 Points 3(6.1) Diagnosis**90 Points 0 Subarachnoid hemorrhage and comorbidities 28(57.1) 100 Points 0 Subdural hematoma 8(16.3) KPS grouping**Subdural hematoma + subdural hemorrhage 14(28.6) Mild (70—100) 6(12.2) Subdural hematoma + hypoxic brain 2(4.1) Moderate (40—60) 17(34.7) Subdural hematoma + cervical trauma 4(8.2) Severe (0—30) 26(53.1) Subdural hematoma and comorbidities 13(26.5) Mobilization**Subdural hematoma 8(16.3) Present 7(14.3) Subdural hematoma + cervical trauma 5(10.2) Absent 42(85.7) Others 8(16.3) Oral nutrition**Epidural hemorrhage 3(6.1) Present 9(8.4) Hypoxic brain 3(6.1) Absent 40(81.6) Axonal injury 2(4.1) PEG**GCS grouping**Present 35(71.4) Mild (13–15) 9(18.4) Absent 14(28.6) Moderate (9–12) 19(38.7)racheostomy**Severe (≤ 8) 21(42.9) Present 32(65.3) GOS**Absent 17(34.7) Good recovery 3(6.1) Pressure ulcer**Moderate disability 5(10.2) Present 23(46.9) Severe disability 27(55.2) Absent 26(53.1) Vegetative state 8(16.3) Discharge**Death 6(12.2) Home 31(63.4) GOS grouping**Rehabilitation centre 6(12.2) Good (moderate disability + good recovery) 8(16.3) Intensive care unit 6(12.2) Moderate (severe disability) 27(55.1) Death 6(12.2) Poor (death + vegetative state) 14(28.6) Variable

Results

Patients and PC requirement

able 2 Evaluation of clinical characteristics and concomitant problems according to GCS, GOS and KPS grouping of the patients

able 2 Evaluation of clinical characteristics and concomitant problems according to GCS, GOS and KPS grouping of the patients

Values are presented as number of cases (percentage). *P< 0.05 (chi‐square test). GCS: Glasgow Coma Score, severe GSC: 3–8, moderate GCS: 9–12, mild GCS: 13–15. GOS: Glasgow Outcome Scale, poor GOS: death and vegetative status, moderate GOS: severe disability, good GOS: moderate disability and full recovery. KPS: Karnofsky Performance Status, severe KPS: 0–30, moderate KPS: 40–60, mild KPS: 70–100.

Mobilization Oral nutrition PEG Tracheostomy Pressure ulcer Absent Present Absent Present Absent Present Absent Present Absent Present GCS Mild 6(12) 3(6) 4(8) 5(10) 7(14) 2(4) 7(14) 2(4) 8(16) 1(2) Moderate 15(31) 4(8) 15(31) 4(8) 7(14) 12(24) 8(16) 11(22) 10(20) 9(18) Severe 21(43) 0 21(43) 0 0 21(43) 2(4) 19(39) 8(16) 13(27)P0.032*0.001*< 0.001*0.001*0.038*GOS Good 3(6) 5(10) 3(6) 5(10) 7(14) 1(2) 6(12) 2(4) 7(14) 1(2) Moderate 26(53) 1(2) 25(51) 2(4) 5(10) 22(45) 7(14) 20(41) 13(27) 14(29) Poor 13(27) 1(2) 12(24) 2(4) 2(4) 12(24) 4(8) 10(20) 6(12) 8(16)P< 0.001*0.002*< 0.001*0.032*0.097 KPS Mild 26(53) 0(0) 26(53) 0 2(4) 24(49) 4(8) 22(45) 10(20) 16(33) Moderate 15(31) 2(4) 13(27) 4(8) 6(12) 11(22) 7(14) 10(20) 10(20) 7(14) Severe 1(2) 5(10) 1(2) 5(10) 6(12) 0 6(12) 0 6(12) 0P< 0.001*< 0.001*< 0.001*< 0.001*0.021

able 4 Comparison of clinical characteristics and concomitant problems according to gender and discharge status

able 4 Comparison of clinical characteristics and concomitant problems according to gender and discharge status

Values are presented as number of cases (percentage). Chi‐square test was used, andP< 0.05 is signi fi cant. OR: Odds ratio; CI: con fi dence interval; PEG: percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. *Discharge to rehabilitation centre, intensive care unit and death.

Female Maleχ2valueOR(95%CI)Pvalue Discharge to home Discharge to other places*χ2valueOR(95%CI)Pvalueracheostomy Absent 9(18.4) 8(16.3) 7.575 6.075(1.578–23.391)0.006 11(22.4) 6(12.2) 0.023 0.909(0.267–3.096)0.879 Present 5(10.2) 27(55.1) 20(40.8) 12(24.5) PEG Absent 5(10.2) 9(18.4) 0.49 1.605(0.424–6.070) 0.484 10(20.4) 4(8.2) 0.562 0.600(0.157–2.297)0.453 Present 9(18.4) 26(53.1) 21(42.9) 14(28.6) Oral nutrition Absent 11(22.4) 29(59.2)0.123 0.759(0.161–3.574) 0.726 25(51.0) 15(30.6) 0.055 1.2(0.261–5.523) 0.815 Present 3(6.1) 6(12.2) 6(12.2) 3(6.1) Mobilization Absent 12(24.5) 30(61.2)0.000 1.000(0.170–5.878) 1.000 25(51.0) 17(34.7) 1.771 4.08(0.45–37.001) 0.183 Present 2(4.1) 5(10.2) 6(12.2) 1(2.0) Pressure ulcer Absent 8(16.3) 18(36.7)0.131 1.259(0.361–4.391) 0.717 15(30.6) 11(22.4) 0.740 1.676(0.515–5.459)0.390 Present 6(12.2) 17(34.7) 16(32.7) 7(14.3)

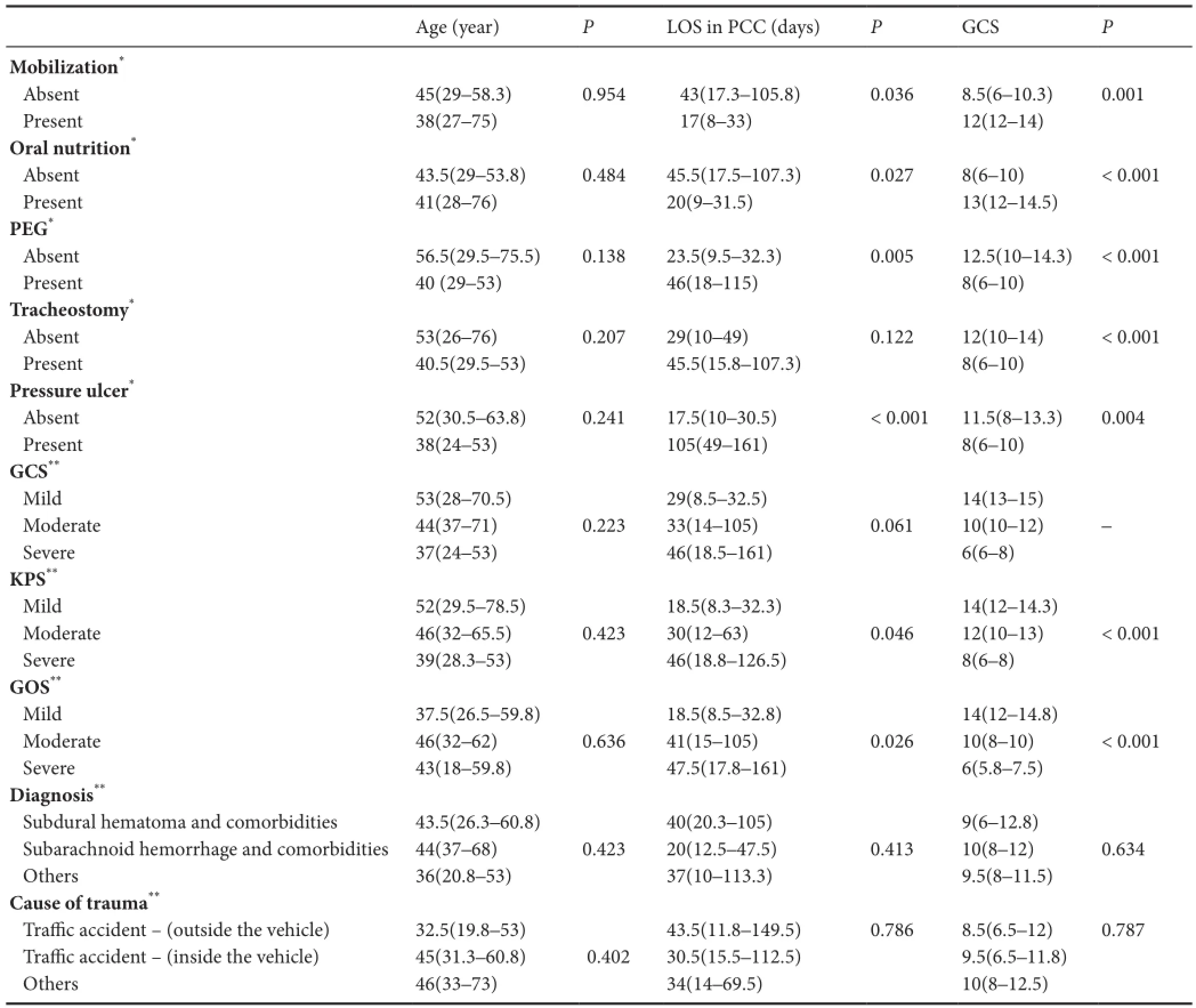

LOS

No signi fi cant di ff erence was determined in the age, LOS in PCC and median GCS of the patients under di ff erent con‐ditions (P> 0.05). There were no significant differences in age (P= 0.423) and LOS in PCC (P= 0.046) between KPS groups (able 3).

Patients subjected to PEG and patients with PU had a signi fi cantly greater median LOS in PCC than those not sub‐jected to PEG and those without PU separately (P< 0.001) (able 3). There were no significant differences in age and LOS in PCC between poor GOS, moderate GOS and good GOS groups (P> 0.05) (able 3). Patients with good GOS had a signi fi cantly greater median GCS than in patients with moderate and poor GOS, and patients with moderate GOS had a significantly greater GCS than in patients with poor GOS (P≤ 0.001) (able 3).

Discharge status

able 3e e ff ects of clinical characteristics and concomitant problems of the patients according to age distribution, LOS in PCC and GCS

able 3e e ff ects of clinical characteristics and concomitant problems of the patients according to age distribution, LOS in PCC and GCS

Values are stated as median (25th–75thpercentile). *P< 0.05 (Mann‐WhitneyUtest is used for comparison). **P< 0.016 (Bonferroni corrected Kruskal‐Wallis tests). LOS: Length of Stay; PCC: palliative care centre; PEG: percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; GCS: Glasgow Coma Score, severe GSC: 3–8, moderate GCS: 9–12, mild GCS: 13–15; GOS: Glasgow Outcome Scale, poor GOS: death and vegetative status, moderate GOS: severe disability, good GOS: moderate disability and full Recovery; KPS: Karnofsky Performance Status, severe KPS: 0–30, moderate KPS: 40–60, mild KPS: 70–100.

Age (year)PLOS in PCC (days)PGCSPMobilization*Absent 45(29–58.3) 0.954 43(17.3–105.8) 0.036 8.5(6–10.3) 0.001 Present 38(27–75) 17(8–33) 12(12–14) Oral nutrition*Absent 43.5(29–53.8) 0.484 45.5(17.5–107.3) 0.027 8(6–10) < 0.001 Present 41(28–76) 20(9–31.5) 13(12–14.5) PEG*Absent 56.5(29.5–75.5) 0.138 23.5(9.5–32.3) 0.005 12.5(10–14.3) < 0.001 Present 40 (29–53) 46(18–115) 8(6–10)racheostomy*Absent 53(26–76) 0.207 29(10–49) 0.122 12(10–14) < 0.001 Present 40.5(29.5–53) 45.5(15.8–107.3) 8(6–10) Pressure ulcer*Absent 52(30.5–63.8) 0.241 17.5(10–30.5) < 0.001 11.5(8–13.3) 0.004 Present 38(24–53) 105(49–161) 8(6–10) GCS**Mild 53(28–70.5) 29(8.5–32.5) 14(13–15) Moderate 44(37–71) 0.223 33(14–105) 0.061 10(10–12) –Severe 37(24–53) 46(18.5–161) 6(6–8) KPS**Mild 52(29.5–78.5) 18.5(8.3–32.3) 14(12–14.3) Moderate 46(32–65.5) 0.423 30(12–63) 0.046 12(10–13) < 0.001 Severe 39(28.3–53) 46(18.8–126.5) 8(6–8) GOS**Mild 37.5(26.5–59.8) 18.5(8.5–32.8) 14(12–14.8) Moderate 46(32–62) 0.636 41(15–105) 0.026 10(8–10) < 0.001 Severe 43(18–59.8) 47.5(17.8–161) 6(5.8–7.5) Diagnosis**Subdural hematoma and comorbidities 43.5(26.3–60.8) 40(20.3–105) 9(6–12.8) Subarachnoid hemorrhage and comorbidities 44(37–68) 0.423 20(12.5–47.5) 0.413 10(8–12) 0.634 Others 36(20.8–53) 37(10–113.3) 9.5(8–11.5) Cause of trauma**Tra ffi c accident — (outside the vehicle) 32.5(19.8–53) 43.5(11.8–149.5) 0.786 8.5(6.5–12) 0.787 Tra ffi c accident — (inside the vehicle) 45(31.3–60.8) 0.402 30.5(15.5–112.5) 9.5(6.5–11.8) Others 46(33–73) 34(14–69.5) 10(8–12.5)

In this study, 49 patients who stayed in PCC were includ‐ ed in this study, and 10 of them died and 4 were transferred to ICU during the 3‐year study period, with a mortality rate of 20.4%. Of the surviving 39 patients, 36 (73%) patients (28 with sequelae and 8 in a vegetative state) were dependent on or needed care, and only 3 were discharged with no sequelae.e high rate of 73% of dependent patients in need of care was thought to be due to terminal‐stage patients having been trans‐ferred from the ICUs of other hospitals for palliative care.

Discussion

TBI is one of the leading causes of morbidity and disability worldwide with a greater economic burden in low and middle income countries, and very little is known about the outcomes after treatment (Hukkelhoven et al., 2003; De Silva et al., 2009; Corrigan et al., 2010). Although the treatment outcomeof surviving TBI patients is associated with many factors, the costs of the condition to the individuals and community are involved in the macro‐level outcomes re fl ecting quality of life and a return to independent living (Narayan et al., 2002; Se‐lassie et al., 2008; Nichol et al., 2011; Hall et al., 2015). TBI in some form develops in approximately 2.5 million individuals per year in Europe, 1 million of these are admitted to hospital and of these 75,000 die (Maas et al., 2015). In the USA, it has been reported that 1.1 million individuals per year are treated in emergency departments with a diagnosis of non‐fatal TBI, 235,000 are admitted to hospital, approximately 50,000 die and 124,000 (43.1%) are discharged from hospital. Long‐term disabilities develop because of TBI and these disabilities form the most signi fi cant obstacle to the continuation of life (Corri‐gan et al., 2010; Jagnoor and Cameron, 2014). Following TBI, there is a need for every kind of care and support which will improve quality of life and the economic situation for those who survive and their families, possibly throughout the life (Nichol et al., 2011; Jagnoor and Cameron, 2014).

Patients in PCC stay in single rooms together with either a family member who undertakes the care or a person pro‐viding professional care. An anesthesia and re‐animation specialist is responsible for the service provided to patients in PCC 24 hours a day and 7 days a week. Specialists from brain surgery, general surgery, internal cardiology, chest diseases, infectious diseases, plastic and reconstructive sur‐gery, physical therapy and rehabilitation work as consulting doctors. Dieticians and physiotherapists also have a function in PCC. In addition to the medical treatment, psychological support is provided for the patient and their family by psy‐chologists and psychological care specialists.

Continuation of life with severe and moderate sequelae is a difficult situation to be accepted by both the patient and their family. In the early stages aer TBI, the patient and their family together require physical, psychosocial, and emotional support. Creutzfeldt et al. (2015) reported that 62% of pa‐tients admitted to neuro‐ICU were de fi ned as in need of PC by ICU clinicians. In recent years, PC has been accepted as a part of comprehensive care for the increasing number of crit‐ical patients, irrespective of diagnosis and prognosis, and has been extremely effective for developing strategies (Aslakson et al., 2014). While KPS is oen used as a prognostic tool in PC, GOS and GCS are used as prognostic tools in ICU. In the current study, patients with good GOS were observed to have signi fi cantly high median GCS and patients in the severe KPS group had signi fi cantly low median GCS. Twenty‐one patients were determined with GCS ≤ 8, as the prognosis was expected to be poor in the majority, and the necessity to implement PC from the time of admittance to ICU was shown.

PEG has become a routine procedure for patients with pro‐longed lack of consciousness after TBI. In this study, only 9 patients could be fed orally and PEG was applied to 35 (71.4%). The ability for oral feeding of patients in PC or nutritional support with PEG, NG or TPN provides signi fi cant positive support especially for the patient’s family. In 32 patients, early tracheostomy was applied because of a prolonged requirement for mechanical ventilation in ICU, but as mechanical venti‐lation could not be applied to these patients in PC, oxygen support was provided at intervals from the tracheostomy can‐nula.e 32 (65.3%) patients subjected to tracheostomy had similar KPS, GOS and GCS values. Cases with tracheostomy performed in the early stage of severe isolated head injury had a decreased LOS in ICU and fewer total days of ventilation (Siddiqui et al., 2015). Impaired nutrition has been reported to affect the formation of PU and has a negative effect on prognosis by increasing mortality (Montalcini et al., 2015). Su ffi cient albumin has a direct e ff ect on neurological injures and improves vital and functional outcomes together with re‐duced oxygenation in secondary brain damage (Bernard et al., 2008; Baltazar et al., 2015). A low GCS score was seen in the severe KPS group and in patients with poor GOS who were not mobilized, had a tracheostomy, had PEG applied, were not fed orally, and had PU.

In patients with PEG who were not fed orally and not mobilized, the LOS in PCC was significantly high. Among patients included in this study, 42 (85.7%) patients were bedridden and 23 (46.9%) patients developed PU, indicat‐ing that other patients without PU who were not mobilized have the risk of developing PU over time.e patients with a TBI and those who have to live together with the patients were considered in this study. Patient’s conditions including tracheostomy, PEG, inability to take oral nutrition, devel‐opment of PU, and inability to be mobile make lives of the patients and their caregivers extremely di ffi cult. At the same time, their quality of life is directly affected. For example, taking prophylactic precautions to prevent PU formation will make a positive contribution to the quality of life of the patient and their family. It would be possible to educate the patient and their family in preventative measures. PCCs are centers where communication is prioritized and the patient and their family can learn how they can live with the situa‐tion they fi nd themselves in (Owens et al., 2005).

Healthcare professionals can facilitate PC services to TBI patients with PC rules and applications (Frontera et al., 2015).ose working in ICU in particular know how com‐munication should be established when sharing information with terminal‐stage patients and their family and as a result the communication is more supportive and empathic (Cur‐tis et al., 2001; Simmons et al., 2008). Simmons et al. (2008) applied PC to patients with intracerebral hemorrhage and reported that those administering PC should help the fam‐ily at the stage of decision‐making for surgery to withdraw technological support and other invasive interventions such as arti fi cial feeding which a ff ects the prognosis. If the family members make a decision not to apply treatment or to close down a life support unit, the clinician will work easily (Owens et al., 2005). In Turkey, the non‐application of treatment or terminating treatment or ‘do not resuscitate’ — DNR orders, are not legal and are not applied. In brain‐dead patients, the decision to close down the life support unit is controversial except for organ transplantation and again is not applied.erefore, in practice, in communication with the families of TBI patients, the subjects of DNR, terminating or not apply‐ing treatment are not discussed and treatment of the patient is continued.roughout the hospitalization period, support was provided by psychologists and emotional care specialistsfor the patient and their family to make them to accept the prognosis and the state of dependency.

In conclusion, there is a very limited amount of data, even almost negligible, related to the PC needs of TBI patients. This retrospective study has shown that TBI patients have complex health conditions entailing high treatment costs and they are dependent on family care after discharge. To improve the quality of life of TBI patients, it is important to determine the PC requirements and to integrate PC with other services according to the principles of PC. Criteria must be de fi ned to be able to implement more e ff ective and better quality PC for these patients.ere is a need for fur‐ther studies on this subject.

Declaration of patient consent:

Author contributions:KK, MD, CD and AKY conceived and designed the study, collected and integrated the data. KK, MD and CD analyzed the data, wrote and reviewed the paper, and were responsible for statistical analysis. All authors approved the fi nal version of this paper for publication.

Con fl icts of interest:None declared.

Supplementary information:Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, by visiting www.nrronline.org.Plagiarism check:This paper was screened twice using CrossCheck to verify originality before publication.

Peer review:

Abernethy AP, Shelby‐James T, Fazekas BS, Woods D, Currow DC (2005)e Australia‐modi fi ed Karnofsky Performance Status (AKPS) scale: a revised scale for contemporary palliative care clinical practice (ISRCTN81117481). BMC Palliat Care 4:7.

Aslakson RA, Curtis JR, Nelson JE (2014)e changing role of pallia‐tive care in the ICU. Crit Care Med 42:2418‐2428.

Baltazar GA, Pate AJ, Panigrahi B, Sharp A, Smith M, Chendrasekhar A (2015) Higher haemoglobin levels and dedicated trauma admission are associated with survival aer severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj 29:607‐611.

Bernard F, Al‐Tamimi YZ, Chatfield D, Lynch AG, Matta BF, Menon DK (2008) Serum albumin level as a predictor of outcome in trau‐matic brain injury: potential for treatment. J Trauma 64:872‐875.

Brennan F (2007) Palliative care as an international human right. J Pain Symptom Manage 33:494‐499.

Buccheri G, Ferrigno D, Tamburini M (1996) Karnofsky and ECOG performance status scoring in lung cancer: a prospective, longitu‐dinal study of 536 patients from a single institution. Eur J Cancer 32A:1135‐1141.

Chahine LM, Malik B, Davis M (2008) Palliative care needs of patients with neurologic or neurosurgical conditions. Eur J Neurol 15:1265‐1272.

Corrigan JD, Selassie AW, Orman JA (2010)e epidemiology of trau‐matic brain injury. J Head Trauma Rehabil 25:72‐80.

Creutzfeldt CJ, Engelberg RA, Healey L, Cheever CS, Becker KJ, Hol‐loway RG, Curtis JR (2015) Palliative Care Needs in the Neuro‐ICU. Crit Care Med 43:1677‐1684.

Curtis JR, Patrick DL, Shannon SE, Treece PD, Engelberg RA, Ruben‐feld GD (2001)e family conference as a focus to improve commu‐nication about end‐of‐life care in the intensive care unit: opportuni‐ties for improvement. Crit Care Med 29(2 Suppl):26‐33.

De Silva MJ, Roberts I, Perel P, Edwards P, Kenward MG, Fernandes J, Shakur H, Patel V (2009) CRASH Trial Collaborators. Patient out‐come aer traumatic brain injury in high‐, middle‐ and low‐income countries: analysis of data on 8927 patients in 46 countries. Int J Epi‐demiol 38:452‐458.

Frontera JA, Curtis JR, Nelson JE, Campbell M, Gabriel M, Mosenthal AC, Mulkerin C, Puntillo KA, Ray DE, Bassett R, Boss RD, Lustbad‐er DR, Brasel KJ, Weiss SP, Weissman DE; Improving Palliative Care in the ICU Project Advisory Board (2015) Integrating palliative care into the care of neurocritically ill patients: a report from the improv‐ing palliative care in the ICU Project Advisory Board and the Center to Advance Palliative Care. Crit Care Med 43:1964‐1977.

Garcia‐Altes A, Perez K, Novoa A, Suelves, JM, Bernabeu M, Vidal J, Arrufat V, Santamariña‐Rubio E, Ferrando J, Cogollos M, Cantera CM, Luque JC (2012) Spinal cord injury and traumatic brain injury: a cost‐of‐illness study. Neuroepidemiology 39:103‐108.

Godbolt AK, Stenberg M, Jakobsson J, Sorjonen K, Krakau K, Stålnacke BM, Nygren DeBoussard C (2015) Subacute complications during recovery from severe traumatic brain injury: frequency and associa‐tions with outcome. BMJ Open 5:e007208

Hall R, Turgeon AF (2015) Palliative care in the neurologic ICU‐are we there yet? Crit Care Med 43:2033‐2034.

Holloway RG, Arnold RM, Creutzfeldt CJ, Lewis EF, Lutz BJ, McCann RM, Rabinstein AA, Saposnik G, Sheth KN, Zahuranec DB, Zipfel GJ, Zorowitz RD (2014) American Heart Association Stroke Coun‐cil, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, and Council on Clinical Cardiology: Palliative and end‐of‐life care in stroke: A state‐ment for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Associa‐tion/American Stroke Association. Stroke 45:1887‐1916.

Hukkelhoven CW, Steyerberg EW, Rampen AJ, Farace E, Habbema JD, Marshall LF, Murray GD, Maas AI (2003) Patient age and outcome following severe traumatic brain injury: an analysis of 5600 patients. J Neurosurg 99:666‐673.

Humphreys I, Wood RL, Phillips CJ, Macey S (2013)e costs of traumat‐ic brain injury: a literature review. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 5:281‐287.

Jagnoor J, Cameron ID (2014) Traumatic brain injury‐‐support for in‐jured people and their carers. Aust Fam Physician 43:758‐763.

Lynch T, Connor S, Clark D (2013) Mapping levels of palliative care de‐velopment: a global update. J Pain Symptom Manage 45:1094‐1106.

Maas A, Menon DK, Steyerberg EW, Citerio G, Lecky F, Manley GT, Hill S, Legrand V, Sorgner A (2015) CENTER‐TBI Participants and Investigators. Collaborative European NeuroTrauma Effectiveness Research in Traumatic Brain Injury (CENTER‐TBI): A prospective longitudinal observational study. Neurosurgery 76:67‐80.

Montalcini T, Moraca M, Ferro Y, Romeo S, Serra S, Raso MG, Rossi F, Sannita WG, Dolce G, Pujia A (2015) Nutritional parameters predicting pressure ulcers and short‐term mortality in patients with minimal conscious state as a result of traumatic and non‐traumatic acquired brain injury. J Transl Med 13:305.

Mosenthal AC, Murphy PA (2003) Trauma care and palliative care: time to integrate the two? J Am Coll Surg 197:509‐516.

Narayan RK, Michel ME, Ansell B, Baethmann A, Biegon A, Bracken MB, Bullock MR (2002) Clinical trials in head injury. J Neurotrauma 19:503‐557.

Nichol AD, Higgins AM, Gabbe BJ, Murray LJ, Cooper DJ, Cameron PA (2011) Measuring functional and quality of life outcomes following major head injury: common scales and checklists. Injury 42:281‐287.

Owens D, Flom J (2005) Integrating palliative and neurological critical care. AACN Clin Issues 6:542‐550.

Selassie AW, Zaloshnja E, Langlois JA, Miller T, Jones P, Steiner C (2008) Incidence of long‐term disability following traumatic brain injury hospitalization, United States. J Head Trauma Rehabil 23:123‐131.

Siddiqui UT, Tahir MZ, Shamim MS, Enam SA (2015) Clinical out‐come and cost e ff ectiveness of early tracheostomy in isolated severe head injury patients. Surg Neurol Int 6:65.

Simmons BB, Parks SM (2008) Intracerebral hemorrhage for the palliative care provider: what you need to know. J Palliat Med 11:1336‐1339.

World Health Organization (WHO) (2015) WHO De fi nition of Pallia‐tive Care. Available at: http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/de fi ni‐tion/en/Accessed.22.06.2016

Copyedited by Li CH, Song LP, Zhao M

Kadriye Kahveci, M.D., kahvecikadriye@gmail.com.

10.4103/1673-5374.198987

*< class="emphasis_italic">Correspondence to: Kadriye Kahveci, M.D., kahvecikadriye@gmail.com.

orcid: 0000-0002-9285-3195 (Kadriye Kahveci)

- 中国神经再生研究(英文版)的其它文章

- Restoring axonal localization and transport of transmembrane receptors to promote repair within the injured CNS: a critical step in CNS regeneration

- Information for Authors -Neural Regeneration Research

- A new computational approach for modeling diffusion tractography in the brain

- Celebration of the 10thAnniversary of Neural Regeneration Research

- Terapeutic potential of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and a small molecular mimics of BDNF for traumatic brain injury

- Blood microRNAs as potential diagnostic markers for hemorrhagic stroke