发现金家坊

李颖春

袁菁

施佳宇

施佳宇 詹强 何威 摄影

谭镭 译

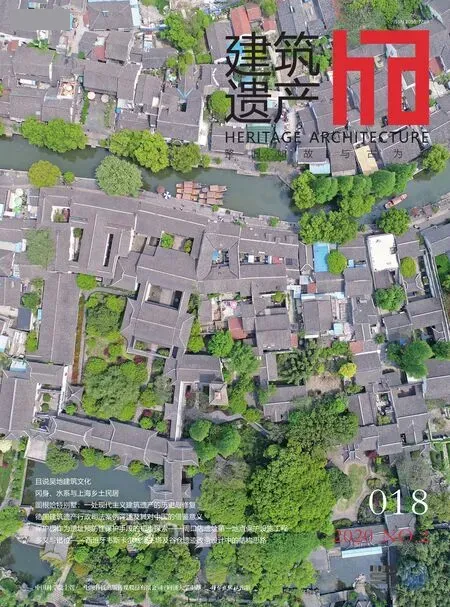

金家坊,位于明清两代上海县城的西北角,占地15 ha,由16 条街道、近500 幢房屋组成。2016 年初启动旧城改造项目之前,这里曾经生活着近5 000 户居民。查阅16—18 世纪的古代地图,这一带是城墙脚下、西门之内的空白地带。①上海地图绘刊史上将1814 年清嘉庆《县城图》刊行到1918 年《袖珍上海新地图》出版之前的时间段称为“近代早期”。据此,19 世纪以前的地图可归为“古代地图”。参见钟翀的文章《近代上海早期城市地图谱系研究》,刊载于《史林》2013 年第1 期8—18 页。它远离政治中心,没有值得标注的机构和地名,甚至在地图上所占的面积也被大幅压缩。

这里本没有名字,我们借用地块内一条主要道路的名字,将其命名为“金家坊”。

2017 年底,我们决定在这里开展研究工作。当时不少居民已经搬离,一个新的规划蓝图也已基本成型。我们对这个即将消失的街区感到好奇,原是希望在这里寻找一些古代留下的痕迹,以填补历史地图上的“留白”。但随着研究的推进,我们发现金家坊的城市空间不能简单地理解为一片古代化石。恰恰相反,它是历史上持续不断建设活动的结果,反映了史书上从未记载的、一代代普通人的生活情境。

于是,我们的工作重心从“古迹寻访”转向了对不同时期日常生活空间的发掘。我们研究工作的第一步,是观察记录由街道和建筑组成的城市物质空间,并对其发展历程各阶段的特征进行分层识别。我们发现,金家坊的街巷间,仍然依稀保留着500 年前城墙、城门和水道的位置;现存道路的宽度和走线,清晰地反映出哪些道路形成于古代,哪些建造于近代。这里各式各样的建筑物,几乎是19 世纪末至20 世纪初上海城市住宅演变的缩影。金家坊虽然缺乏一种明快简洁的空间秩序,但这并不意味着历史风貌的衰败,而恰恰是不同时期历史残片层叠和拼贴形成的独特景观。

金家坊一带有着异常丰富、难以被“归类”的住宅形态。每一组建筑背后,都是一位具象的产权人。通过对现存地界石碑的字迹辨析,以及零星的访谈和历史资料,我们发现20 世纪初期,这里的房屋业主大多为从事或参与商业活动的华人。与租界内实力雄厚的华洋资本偏爱的成片里弄相比,金家坊一带的华人中小业主们更倾向于在不到1 亩(约500 ~600 m2)的小地块内进行精打细算的混合开发,将自住、出租、商业、工坊等功能融为一体,造就了这一带丰富灵动的街道立面。②相似的情况也存在于老法租界地区,参见刘刚的文章《近代上海租界的土地重划与自主开发》,刊载于《时代建筑》2018 年第6 期126—130 页。

随着调研的深入,我们与这里的居民渐渐熟悉,并开始记录他们在老城最后的生活日常。对于不少居民来讲,这些位于城市中心的小小房屋,不仅是生活场所,也是谋生手段。“烟纸店”可能是其中最典型的例子。烟纸店老板们在通常属于自家的房子里,一边经营生意,一边照料家务,同时不耽误享受生活中的小乐趣。所有的时间和空间都是自己的,这种“自由”和“方便”似乎不能简单地用金钱来计算。

金家坊不是伟大的城市规划作品,也没有重要的文物古迹,但这个古代地图上的“留白”深深地打动了我们。在这里,我们看到的是历史上的普通人,在既有的政治经济制度条件下,利用区位、土地和房屋在城市中求取最好的生存状态,由此形成独特的城市景观、生活方式和社区记忆。这一轮的城市更新,会给金家坊带来怎样的空间与生活?离开金家坊的人们,又将如何在新的环境下延续各自的生活?我们将继续观察。

Jinjiafang is located at the northwest quadrant of the walled city of Shanghai County in the Ming and Qing dynasties. It occupies an area of 15 ha, consisting of 16 streets and almost 500 houses. Before the initiation of the urban renewal project in 2016, there used to be nearly 5,000 households residing in this area. According to the historical maps from the 16thto 18thcenturies, the Jinjiafang neighbourhood was an ‘empty land’ within the West Gate of the town, adjacent to the city wall.①The maps published between 1814 and 1:918 were considered as ‘early modern’ in the study of the survey and publish history of Shanghai maps. Thus, maps published before 1800 can be categorized as ‘ancient maps’. See ZHONG Chong. Study on City Map Pedigree in the Early Time of Modern Shanghai [J]. Shiling, 2013 (1): 8-18.It was far from the political centre of the town, and there was no institution or landmark worth noting on the maps. Even its area on the map was significantly compressed compared to reality.

Initially, this area did not have a name. We are naming it Jinjiafang according to the longest street in the neighbourhood.

At the end of 2017, we started a study on the Jinjiafang neighbourhood. Many residents had already moved away by then, and the blueprint of a new urban plan had been formed. Initially, we were curious about this disappearing neighbourhood as we were hoping to find some traces left from the ancient times and fill in the ‘emptiness’ on the historical maps. However, as the survey continued, we realised that this piece of urban artefact should not be simply understood as some fossils left from the pre-modern period. Instead, it is a collage of fragments from the continuous construction activities from ancient times to the present, reflecting the very real situations of ordinary people’s everyday life that have not been recorded in any oきcial documents.

Therefore, we decided to shift our focus from ‘searching for ancient relics’ to the exploring of the everyday urban space in diあerent historical periods. The first steps of our research were to observe and document the physical urban space that consists of streets and buildings. We realise that the approximate locations of the city wall, city gate and waterways from 500 years ago can still be traced among the streets of Jinjiafang. Streets formed in pre-modern times and the recent past can be clearly differentiated by measuring and analysing the widths and paths of the current streets. The variety of buildings presents a near epitome of Shanghai’s urban housing evolution from the late 19th century to early 20th century. There seems to be a lack of apparent spatial order in Jinjiafang, but it is not the representation of a ruinous historic appearance. Instead, it is a unique urban landscape composed of multiple historical layers and fragments.

The Jinjiafang neighbourhood contains an exceptional variety of housing forms which are difficult to ‘categorise’. Behind each group of buildings there was a particular owner. Through documentation of the boundary stones, on-site interviews and scattered historical information, we discovered that these property owners were mostly Chinese, either being merchants or engaged in commercial activities, most of them moved into the old town from elsewhere around the late Qing Dynasty and early Republic of China (ROC) era. Compared with the largescalelilonghouses for rent favoured by the big foreign and Chinese developers in the International Settlement and French Concession, these Chinese petit landowners were more inclined to carry out carefully calculated mix-used development within a small piece of land less than 1mu(around 500-600 m2), creating the vivid streetscape in this area.②Such development mode can also be found in the old French Concession. See Liu Gang, “Land Adjustment and Self-Organized Development in Early Modern Shanghai Foreign Settlement.” Time + Architecture 2018 (6): 126-130.

As our survey continued, we got to know more about the residents, and started documenting their last episodes of daily life in this neighbourhood. We found that for many residents, these small houses in the city centre are not only their homes but also their ways to earn a living. ‘Tobacco shops’ are probably among the most typical examples. The shop owners took care of their households and manage their businesses in their homes, in the meanwhile not missing out on enjoying the fun of life. All the time and space are theirs to steer. Such a sense of ‘freedom’ and ‘convenience’ cannot be assessed simply on monetary terms.

Jinjiafang is not a product of magnificent urban planning; neither does it embody any cultural or political significance. However, this piece of ‘emptiness’ on the antiquated maps has touched us deeply. Here, we see how generations of ordinary people pursued the best life they could under the existing socio-political conditions, making use of the available location, land, and housing. All these have given rise to a unique urban landscape, lifestyle, and community memory. What kind of space and life will this round of urban renewal bring? How will people carry on their lives in the new environment after they leave here? Our observation in Jinjiafang shall continue.

- 建筑遗产的其它文章

- 德国建筑遗产行政司法案例评述及其对中国的借鉴意义