Hemophagocytic syndrome as a complication of acute pancreatitis:A case report

Chao-Qun Han, Xin-Ru Xie, Qin Zhang, Zhen Ding, Xiao-Hua Hou

Chao-Qun Han, Xin-Ru Xie, Zhen Ding, Xiao-Hua Hou, Division of Gastroenterology, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, China

Qin Zhang, Division of Pathology, Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan 430022, China

Abstract

Key words: Haemophagocytic syndrome; Acute pancreatitis; Immunosuppressive therapy

INTRODUCTION

Haemophagocytic syndrome (HPS) is an uncommon disorder that may be characterized by fever, peripheral blood pancytopenia, liver dysfunction, coagulation abnormalities, and hepatosplenomegaly[1,2]. It may be triggered by genetic disorders,malignant neoplasms, viral infections, and autoimmune disorders[3-5]. Acute pancreatitis (AP) and HPS are sporadically observed in the course of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) or fulminant ulcerative colitis secondary to autoimmune diseases[2,6,7]. We herein report such a case to share our experience with its diagnosis and treatment.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 46-year-old man was admitted for symptom of persistent abdominal pain, nausea,and vomiting for 2 d after heavy drinking and then transferred to our hospital.

History of present illness

The patient’s symptoms started with mild abdominal pain, which had worsened in the last 2 h.

History of past illness

He had no previous history except for smoking.

Physical examination

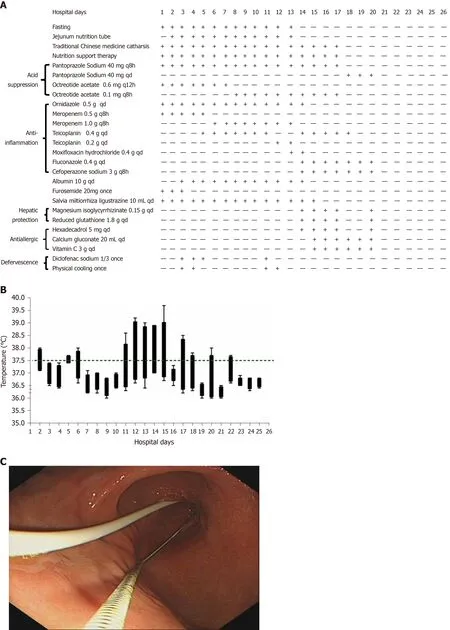

The physical examination on admission revealed a discontinuous fever (38 °C) (Figure 1B) and upper abdomen tenderness. His skin was normal.

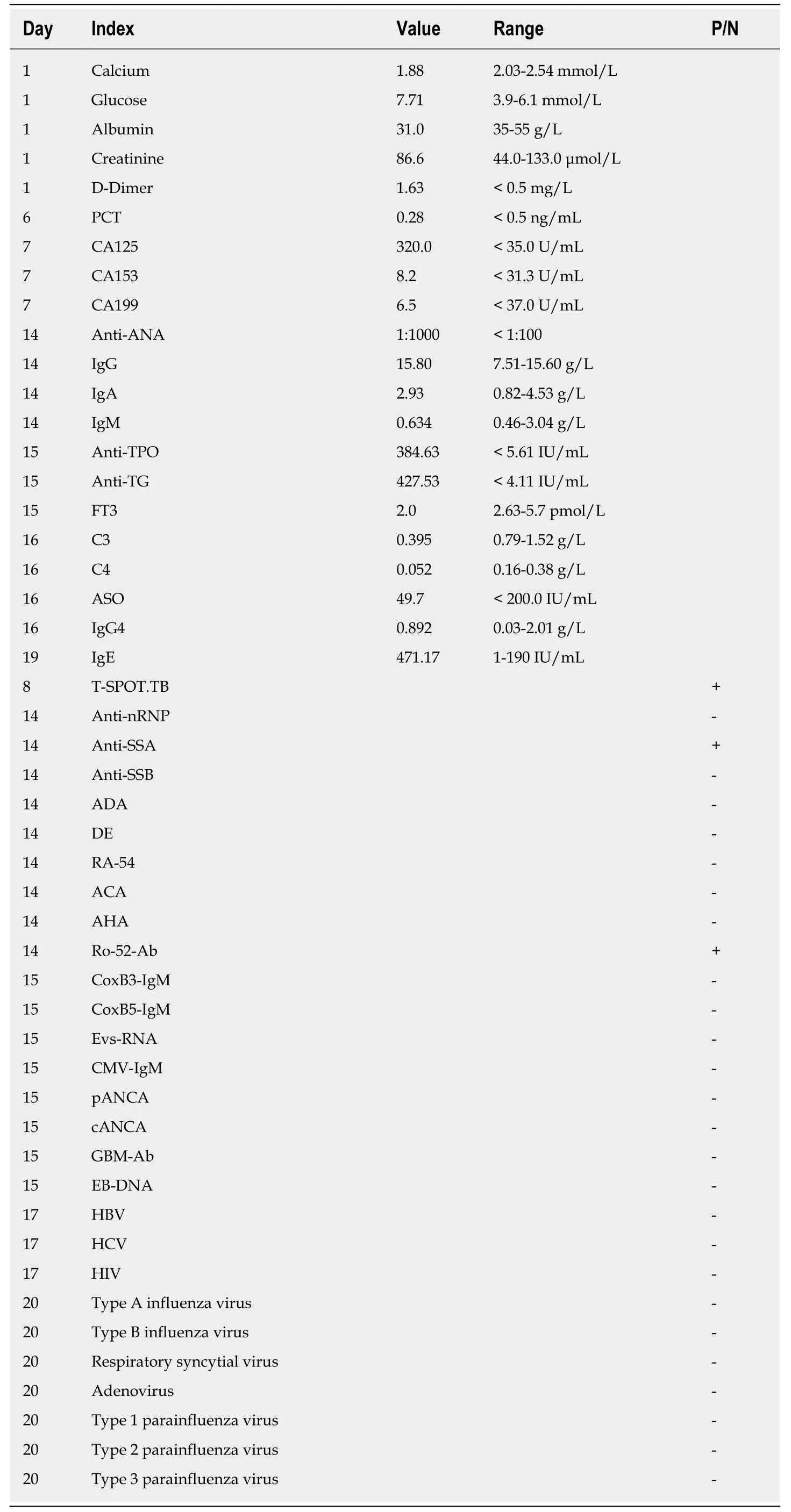

Laboratory examinations

The laboratory data showed significantly increased serum levels of amylase (1454.9 U/L), lipase (1705.28 U/L), white blood cell count (17 G/L), positive C-reactive protein (4.8 mg/mL), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (58 mm/h) (Figure 1D-F),slightly elevated glucose (7.71 mmol/L) and D-dimer (1.63 mg/L), slightly reduced calcium (1.88 mmol/L), and hypoalbuminemia (31.0 g/L). The coagulation, hepatic,and renal functions were all within normal limits. The detailed laboratory values are described in Table 1.

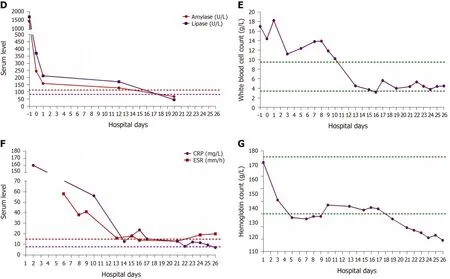

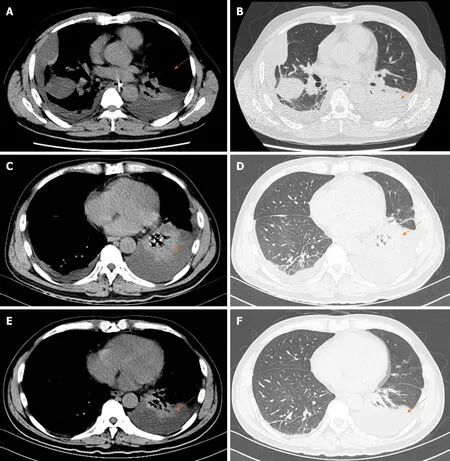

Imaging examinations

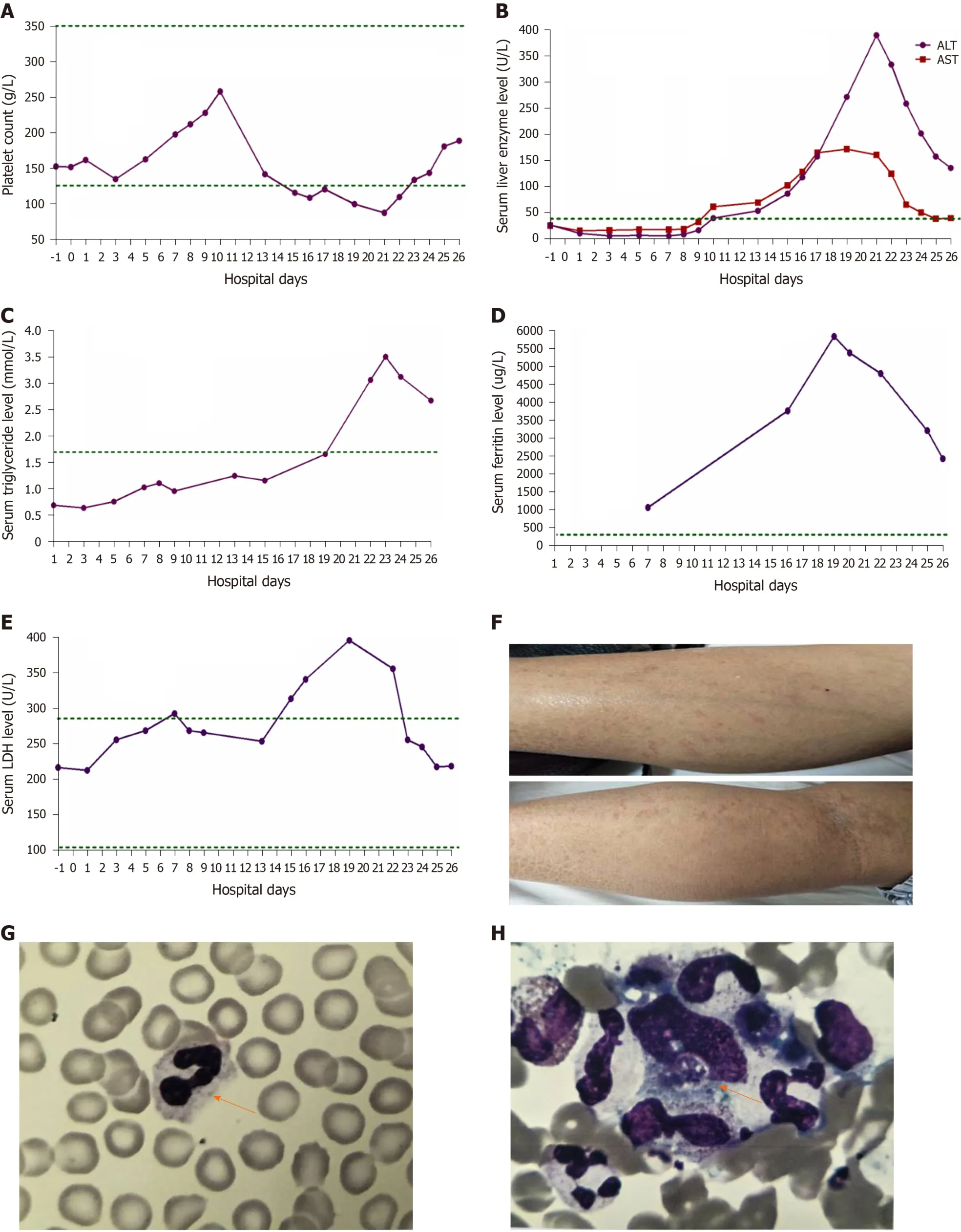

Pancreatic enlargement and peripancreatic seepage on computerized tomography confirmed the diagnosis of AP (Figure 2). Then, the patient was given enteral nutritionviaa jejunal nutrition tube (Figure 1C) and treated with pantoprazole sodium (40 mg per 8 h), octreotide aetate (0.6 mg/q12h), and anti-inflammatory drugs(ornidazole 0.5 g/q8h, meropenem 0.5 g/q8h,etc.). Traditional Chinese medicine catharsis was performed for the prevention of intestinal function failure (Figure 1A).The symptoms of the patient gradually disappeared. He had no febrile and each index was close to the baseline level (Figure 1D-F). Bilateral pleural effusion was absorbed better than before (Figure 3). Surprisingly, from the hospital days 11 to 17, the patient suddenly developed a secondary fever and the highest temperature reached 39.7 °C(Figure 1B). We strengthened the antibiotic treatment, including antifungal therapy,although blood culture did not find any evidence of bacterial or fungal infection.Unfortunately, although the temperature was controlled, his general condition deteriorated. On day 16 after hospitalization, he developed a rash on the trunk, upper limbs, and cruses (Figure 4F), then the indexes of autoimmune disease (e.g., SLE),such as anti-ANA (1:1000), anti-SSA (+), Ro-52-Ab (+), IgG (15.80 g/L), and IgE (471.1 IU/mL), were evaluated. Additionally, he also developed pancytopenia (3.18 g/L of white blood cells, 109 g/L of hemoglobin, and 88 g/L of platelets), hepatic dysfunction (alanine aminotransferase [ALT], 390 U/L; aspartate amino transferase[AST], 172 U/L), and a marked elevation of triglyceride (3.51 mmol/L), ferritin (5850 μg/L), and serum lactic acid dehydrogenase (LDH, 396 U/L) (Figure 4A-E), but his coagulation function was normal without significant abdominal ultrasonography findings.

Figure 1 Results of examinations. A: Detailed therapeutic measures taken for the patient with acute pancreatitis during the time of hospitalization. Nutrition support therapy included 5% glucose, compound sodium chloride, hetastarch, mix sugar electrolyte, fructose, compound amino acid peptide, glutamine dipeptide, multivitamin, and fish oil fat emulsion; B: Temperature change curve of the patient. The measuring frequency was four times a day; C: Jejunum nutrition tube was placed by gastroscopy; D-G: Changes of amylase, lipase, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and hemoglobin during hospitalization.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Based on the above findings, a diagnosis of HPS was highly suspected and a peripheral blood smear and bone marrow examination were planned due to the complicated symptoms. Hemophagocytic cells were found in peripheral blood smears(Figure 4G) and the bone marrow examination showed a histiocytic reactive growth and prominent hemophagocytosis (Figure 4H). Thus, HPS as a complication of AP was finally diagnosed.

TREATMENT

The patient was then treated with liver-protecting drugs, antiallergic drugs, and hexadecadrol 5 mg/d for 4 consecutive days. By day 20, his symptoms of pancytopenia, liver function, and LDH and ferritin elevations were improved. On the day that the patient left the hospital (day 26), the laboratory parameters were largely close to the baseline levels again.

Anti-SSA: Anti-Sj gren syndrome A antibody; Anti-SSB: Anti-Sj gren syndrome B antibody; ADA: AntidsDNA antibody; DE: Anti-ribosomal P protein antibody; RA-54: Anti-nucleosome antibody; ACA: Anticardiolipin antibody; AHA: Anti-histone antibody; Ro-52-Ab: Ro-52 antibody; Cox: Coxsackievirus; Evs:Enterovirus; CMV: Cytomegalovirus; pANCA: Anti-antineutrophilic perinuclear antibody; cANCA: Antiantineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody; GBM-Ab: Glomerular basement membrane antibody; EB: Epstein-Barr virus; HBV: Hepatitis B virus; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus.

Table 1 Laboratory findings for the patient with acute pancreatitis during hospitalization

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

At the 1-mo follow-up visit after discharge, the patient did not take any drugs and had no symptoms or signs without any recurrence.

DISCUSSION

Other abnormal clinical and laboratory findings consistent with the diagnosis of HPS include cerebromeningeal symptoms, jaundice, edema, lymph node enlargement, skin rash, hepatic enzyme abnormalities, hypoproteinemia, and hyponatremia[8]. In the present case, the symptoms of patient gradually recovered after effective treatment.However, the results of laboratory re-examination were incomprehensibly deteriorative. He developed a secondary fever, rash, pancytopenia, hepatic dysfunction, hyperferritinemia, and elevation of serum triglyceride and LDH levels.The bone marrow examination proved that he had concurrent HPS[9].

He had no remarkable past medical history, therefore we first considered if HPS was bacteria or virus-associated or malignancy-associated. However, no active infections with viruses as coxsackievirus, enterovirus, cytomegalovirus, hepatitis B virus, Epstein-Barr virus and other respiratory tract infective viruses were observed.Neither prominent hemophagocytosis nor hematological malignancies were detected.There were also no abnormal findings on abdominal CT and tumor markers analysis except slightly elevated CA125. We also suspected concurrent autoimmune diseases because HPS was reported more commonly in patients with pre-existing SLE.However, besides some autoimmune antibodies showing positive expression, no evidence suggested an underlying autoimmune disease.

There was another possibility that HPS was the side effect of pharmaceutical treatment. We indeed used some drugs that could cause rash, pancytopenia, and hepatorenal dysfunction,e.g., antibiotics such as cefoperazone sodium, fluconazole, or teicoplanin and other acid suppression drugs such as pantoprazole sodium. However,all of these are generally well tolerated and therapeutic measures were appropriate[10-13]. Additionally, some common adverse reactions of these drugs, such as headache, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and pruritus did not occur[14-17]. Therefore,the possibility that it was the side effect of pharmaceutical treatment was ruled out.

HPS is a rare extrapancreatic manifestation of AP. A ambiguous association between AP and HPS was first mentioned in 1998 by Kanajiet al[2], who found HPS associated with fulminant ulcerative colitis and concurrent AP. So far, there have been just two reports about HPS associated with AP in patients with SLE disease.

CONCLUSION

We have described the first case of HPS as a complication of AP, which was successfully treated with immunosuppressive therapy. HPS is a severe condition which requires both early diagnosis and treatment, and HPS as one of the extrapancreatic manifestations of AP should be considered in the future.

Figure 2 Images of abdominal computed tomography. A and B: Contrast-enhanced computed tomography imaging of the pancreas showed pancreatic swelling,peripancreatic infiltration, and bilateral fascia thickening on the fourth day of hospitalization; C and D: The pancreatic swelling and peripancreatic fluid collections were meliorated on day 13; E and F: The peripancreatic seepage almost recovered on day 23.

Figure 3 Images of thoracic computed tomography. A and B: On the fourth day, thoracic computed tomography showed bilateral pleural effusion with partially encapsulated effusion. The lungs also showed scattered linear and lamellar high-density shadows, which were considered to be due to an infectious disease; C and D: Thoracic computed tomography indicated that encapsulated effusion was gradually absorbed but the left lung showed segmental atelectasis on day 13; E and F:Bilateral pleural effusion completely disappeared and segmental atelectasis was recovered on day 23.

Figure 4 Changes of indexes after effective treatment. A-E: Changes of platelets and serum levels of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate amino transferase,triglyceride, ferritin, and lactic acid dehydrogenase during hospitalization; F: The patient suddenly developed skin rash; G: No obvious abnormality was found in the peripheral blood smear (original magnification, 1 × 103); H: Overactive macrophage phagocytosis, erythrocytes, leucocytes, platelets, and their precursors were also not found in the bone marrow aspiration specimen (original magnification, 1 × 103). ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; AST: Aspartate amino transferase.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to the patient for participating in the study.

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年11期

World Journal of Clinical Cases2020年11期

- World Journal of Clinical Cases的其它文章

- Tumor circulome in the liquid biopsies for digestive tract cancer diagnosis and prognosis

- Isoflavones and inflammatory bowel disease

- Cytapheresis for pyoderma gangrenosum associated with inflammatory bowel disease: A review of current status

- Altered physiology of mesenchymal stem cells in the pathogenesis of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis

- Association between liver targeted antiviral therapy in colorectal cancer and survival benefits: An appraisal

- Peroral endoscopic myotomy for management of gastrointestinal motility disorder