沃菲尔德风土图记 XVII空中读村①

——航拍无人机视阈里的传统聚落

刘涤宇

戴方睿

谭镭 译

李颖春 译校

从飞机上我看到了可以称之为宇宙的景象,它提醒我们什么才是这个地球上最根本的东西。

……

在500—1 000 m 的高空,以每小时180—200 km 的速度俯瞰大地,看见的景色不是一晃而过的,它是缓慢、连续,又相当精确的,一个人甚至能分辨牛背上红色和黑色的斑点。除了飞机以外,只有海上的轮船和行人的双足能够提供所谓的人性化视阈。当一个人能看见的时候,他的眼睛可以平缓地向大脑传输这些信号。

——勒 · 柯布西耶③引自勒 · 柯布西耶《精确性》陈洁译本,中国建筑工业出版社2009 年版,pp. 4-7。

航拍无人机的普及,给了我们一种成本低廉的空中读村方式。尽管我们只能从传输过来的图像信息中体验这种来自上空的俯瞰视角,无法获得柯布西耶所描述的那样直接的高空身体体验,高度和速度也不太一样。

起飞前,镜头传输的景象与眼前所见无异:面向街道的房屋、灰瓦的坡顶、檐下的装饰。随着螺旋桨开始转动,熟悉的景象开始一点点推远,院落结构以及邻里关系逐渐浮现出来,然后又随着航拍无人机的进一步升空而凝缩直到不可见。

无论在哪种视阈层次中,水都是传统村落中不可缺少的元素。伴随着村落邻里尺度的是流过村落的小溪、日常生活的水塘,乃至赋予水体一种宗教仪式感的水口亭和水口庙。随着视阈继续扩展,山间的陂塘、密布河网的圩田、河上的桥梁和围堰……在村落逐渐凝缩为大地景观中一个微不足道却足够醒目的点时,这些村落赖以生存的基础设施开始呈现出来,湖州和孚镇荻港村的圩田、苏州震泽师俭堂的河街,都是被称为“江南水乡”的太湖流域地区由水塑造出的农业、商业景观。在西南地区,如果沿河的聚落同时也与起伏动人的山势相伴,聚落与自然地形之间的丰富性便会进一步被激发。重庆塘河镇那从山脊延续而下并深入水中的形态,在航拍无人机的视阈里尽显其飘逸和灵动。

水也可以与其他防御设施结合,形成设防聚落。由于各地地理条件和建造方式的差异,以及防御系统的区别,呈现出风土聚落可贵的多样性。北方聚落多为集村,山西沁水湘峪村选择修筑城墙、建造高楼来自卫;而西南聚落多散村,平原聚落建造配有碉楼的庄园,而山地聚落则凭借天险建造堡寨。水塘是村落中重要的日常生活空间。义乌雅治街翰林第旁的那片水塘,亲切而较少仪式性,但义乌乔亭的另一处水塘却因为旁边有了文化剧院,而呈现出若有若无的仪式感。东阳紫微山民居将方形水塘设置于聚落轴线的核心位置,其作为仪式空间的意义也因此强烈凸显。

紫微山民居建筑群前面的水塘、后面的小山和风水林、严整的轴线所产生的秩序感,与浙中地区村落相对严密的宗族组织密切相关。但即使共享同样的建造方式和相似的宗族组织形态,村落的具体面貌也千差万别。东阳的卢宅,一个超大规模的肃雍堂便限定了村落的基本走向和形态,浦江潘周家村则呈现出由若干较大的院落各自控制其周边区域的形态,而义乌田心村有一大片区域,小型院落围绕曲折的溪水均布。在浙南山区的石仓源,可以看到在河谷有限的耕地之间散布着聚族而居的大屋,村落与田野如十指相扣般交错共生,但与石仓源相邻的山头村畲族聚落却选择沿等高线跌落布置的形态。

完整的几何形状往往使聚族而居的大宅更具有标识性,尤其是当航拍无人机升到高空的时候。福建华安大地村的几座圆形土楼不仅仅在高空,在低空甚至地面上也能体察其向心性的巨大控制力。而三明地区的土堡就不一样,高空中鸟瞰可以感知到强烈的向心控制力,在地面上体验以与日常生活相关的一个个院落为主。

相应地,无人机降落的过程也是从柯布西耶所谓“宇宙的景象”回归日常的过程。空中看上去那种强烈的秩序感逐渐消隐,每家每户各自的细节也开始逐渐呈现。这些日常背后有空中所见的秩序感在背后起作用,然而,作用的机制却潜藏在地面视角所感触到的细微区别中。

亲自走在乡间道路上的感受与乘飞机从上面飞过时的感受是不同的……飞机上的乘客仅仅看到道路如何在地面的景象中延伸,如何随着周围地形的伸展而展开,而只有双脚走在这条路上的人才能感觉到道路所拥有的力量,才能感觉到它是如何从对于飞行员来说只是一马平川的景观中凭借每一次转弯呼唤出了远近、视点、光线和全景图,就像指挥官在前线调兵遣将似的。

——本雅明①引自本雅明《单行道》王才勇译本,江苏人民出版社2006 年版,pp. 12-13。

From the plane I saw sights that one may call cosmic. What an invitation to meditation, what a reminder of the fundamental truths of our earth!

……

At 500 to 1,000 meters altitude, and at 180 to 200 kilometers an hour, the view from a plane is not rushed but slow, unbroken, the most precise one can wish: one can recognise the red or black spots on a cowskin. Everything takes on the precision of a tracing; the spectacle is not rushed but very slow, unbroken; along with the plane, it is only the steamer on sea or the feet of the pedestrian on a road that can give what may be called sight at human scale: one sees, the eye transmits calmly.②Le Corbusierās Precisions on the Pr esent State of Architecture and City Planning (trans. Tim Benton), Park Books, 2015, pp. 4-7.

Le Corbusier

The popularisation of drones has provided a low-cost means to read villages from the air, though we can only experience this bird’s-eye view from above through imageries. It is not the same as the in-person experience described by Le Corbusier. The height and speed are also different.

Before taking off, the scenery from the drone’s camera is not different from what we can see in front of our eyes: houses, streets, sloped roofs and the decorations under the eaves. As the point of sight goes up, this familiar scenery is gradually pushed away. The courtyards and the neighbourhood’s spatial fabric begin to emerge and then zoom out of sight as the drone lifts further off.

Water is a ubiquitous element in traditional villages, whichever perspective we take. On the scale of villages, water can be seen as creeks winding through villages, meres that provide for everyday use, pavilions and temples at embouchures which endow religious and ritual meanings to water. As we zoom out, the meres among mountains, polders in the lowlands, bridges and dykes on the rivers start to emerge. These infrastructures on which the livelihoods of villages rely only come into perspective when villages shrink into noticeable yet negligible dots in a vast landscape. The polders around Digang Village, Hefu Town in Huzhou and the riverside streets around the Shijian Hall of Zhenze Town in Suzhou are part of the agricultural and commercial landscapes carved out by water in the Taihu Lake Basin, commonly known as Jiangnanshuixiang(water town). In Southwest China, the diversity of relationships between settlements and terrains is enhanced when settlements along the rivers are accompanied by the mountains. In Tanghe Town in Chongqing, the way the townscape extends from the mountain ridge into the midst of water appears elegant and nimble in drone images.

Water can also protect the settlements. The variety of topographical conditions, construction methods and defensive systems demonstrate the precious diversity of vernacular settlements. Settlements in North China tend to cluster. Like Xiangyu Village of Qinshui County in Shanxi Province, they opt for constructing walls and towers for self-defence. In Southwest China, on the other hand, settlements are dispersed. Those on the plains built manors withdiaolou(watchtowers), while those in the mountains created fortresses on the cliff. Ponds are significant everyday space in villages. The pond next to the Hanlin Residence on Yiwu’s Yazhijie Village feels informal and intimate. In comparison, another pond at Qiaoting Village in Yiwu gains a faint sense of formality due to the cultural theatre next to it. The Ziweishan Village in Dongyang, on the other hand, significantly highlights the pond by positioning it along the axis of the settlement.

At Ziweishan Village, the sense of order created by the pond in front of the vernacular courtyards, the small mound andfengshuiforest at the backdrop, as the highly visible axis, is closely related to the lineage corporation in villages of central Zhejiang. Although with the same construction methods and similar lineage structures, the form of each village varies significantly. At the Lu Family Mansion in Dongyang, the enormous Suyong Hall alone determines the alignment and pattern of the entire village. Panzhoujia Village in Pujiang demonstrates a pattern where each of several large courtyards controls its peripheral territory. In contrast, Tianxin Village of Yiwu occupies a large area where small courtyards are distributed evenly along the winding creek. At Shicangyuan region in the mountainous area of south Zhejiang, large courtyards occupy agricultural fields in the valley’s limited space. In the neighbouring Shantou Village, however, the settlement of the She people was built along the contour lines.

Complete geometric layouts highlight the large mansions, especially when seen from drones flying high above. The round Tulou in Dadi Village of Hua’an, Fujian Province demonstrates an enormous centripetal control with their layouts from all angles. Whereas thetubao(earth fortress) in Sanming area presents a different dynamic, its intense centripetal control can only be sensed from a bird’s-eye view. At the same time, the experience on the ground is dominated by everyday life in each courtyard.

Respectively, the descending of a drone resembles Le Corbusier’s description of returning to the everyday from the ‘cosmic’. The intense sense of order seen from the sky gradually fades away, while the details of each household slowly emerge. Behind the everyday is the manifestation of the sense of order seen from the air. The generative mechanisms are hidden behind the subtle varieties experienced on the ground.

The power of a country road is different when one is walking along it from when one is flying over it by airplane……The airplane passenger sees only how the road pushes through the landscape, how it unfolds according to the same laws as the terrain surrounding it. Only he who walks the road on foot learns of the power it commands, and of how, from the very scenery that for the flier is only the unfurled plain, it calls forth distances, belvederes, clearings, prospects at each of its turns like a commander deploying soldiers at a front.③Walter Benjaminās One-Way Street and Other Writings, NLB, 1979, p50.

Walter Benjamin

作者简介:刘涤宇,同济大学建筑与城市规划学院(上海 200092)副教授

戴方睿,同济大学建筑与城市规划学院(上海200092)博士研究生

收稿日期:2019-11-17

Biography: Liu Diyu, Associate Professor at the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University (Shanghai 200092)

Dai Fangrui, PhD Candidate at the College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University (Shanghai 200092)

Received date: 17 November, 2019

江苏省苏州市震泽镇师俭堂:全国重点文物保护单位 Shijian Hall in Zhenze Town, Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, listed as National Protected Cultural Heritage Site(戴方睿摄影)

随着明清江南手工业的发展和商品经济的繁荣,沿着运河,诸多市镇应“运”而生。整个长江流域的物资集散于此,富可敌国的江南望族聚居于此。震泽的师俭堂所代表的就是江南儒商居住文化的典范。埠头、商铺沿河展开,祠堂、书塾,还有园林垂直于河街生长,方寸之中腾挪,旷奥之间变换,无名的香山帮匠人以其精妙的布局和典雅的审美,造就了江南特有的大隐隐于市。

Due to the development of manufactural industries and prosperity of the town economy in the lower reaches of Yangtze River during Ming and Qing dynasties, many towns emerged along the canals. Many cargo logistic services and prominent families gathered around here. The Shijian Hall of Zhenze Town is an example representing the culture of Confucianism and commerce in this area. Docks and shops unfold along the canals, while ancestral halls, private school and classical gardens are arranged perpendicular to the riverside streets. The local craftsmen with elegant aesthetics were good at building delicate architecture in limited space.

重庆市江津区塘河镇:中国历史文化名镇 Tanghe Town in Jiangjin District, Chongqing, listed as China’s Historical and Cultural Town(戴方睿摄影)

同样是沿河而兴的市镇,丘陵地带古镇的形态特征便与平原完全不同。溯长江而上,在由于山丘阻隔而变得蜿蜒曲折的支流中,山城重庆的塘河古镇因其地处江弯凸岸而形成了独特的垂直于河道的街市空间。古镇的肌理与山脊延伸而下的动势高度吻合,大山的轮廓抽象成层层叠叠、飘逸连绵的坡屋顶,覆盖在了山脚江岸之上。高低错落的悬山屋顶和编织感强烈的穿斗墙体,仿佛在展现川渝码头特有的不羁性格。

Ancient towns in the mountainous region have different formal characters from those on the plains, although they both heavily rely on waterway transportation. Upstream of the Yangtze River, the winding river branches were shaped by the hills. In Tanghe Town of Chongqing, the U-turn of the river gave birth to its unique street pattern that is perpendicular to the river. The landscape character consists of mountain ridge, the town fabric, the layered slope roofs and the vernacular wall structures, just like the forthright character of the local people in Sichuan and Chongqing regions.

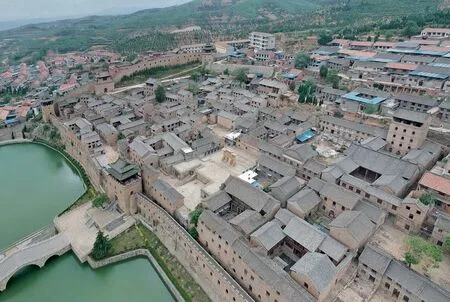

山西省晋城市沁水县湘峪村:全国重点文物保护单位 Xiangyu Village of Qinshui County, Jincheng, Shanxi Province, listed as National Protected Cultural Heritage Site(戴方睿摄影)

四川省泸州市泸县屈氏庄园:全国重点文物保护单位 Qu Family Manor of Lu County, Luzhou, Sichuan Province, listed as National PCHS(戴方睿摄影)

在晋东南沁河流域,权臣贵胄回乡修建的家族堡寨并不少见。湘峪村背山面水,三面修筑城墙,内院再起高楼。远在西南泸县的屈氏庄园虽然也三面环水,但是高耸的碉楼建在四角,对外表现出一种威严。另外,成都平原的聚落分布形态与山西家族聚居不同,屈氏家族有多处庄园,每个庄园建造时间各异,分散在屈氏家族的领地之内。

Along the basin of Qin River in Southeast Shanxi, the fortress settlements are very common. Xiangyu Village is surrounded by walls on three sides, with water in front of it and the mountain as a backdrop. There are also tall buildings in the courtyards inside. Similarly, the Qu Family Manor in the distant Lu County in Southwest China is surrounded by water with talldiaolou(watchtowers) dominating the four corners, exhibiting a sense of dignity to the outer world. The distribution of settlements on the Chengdu plains is different from the clustered ones in Shanxi. The Qu Family owned several manors built in different times, dispersing around the territory of the family.

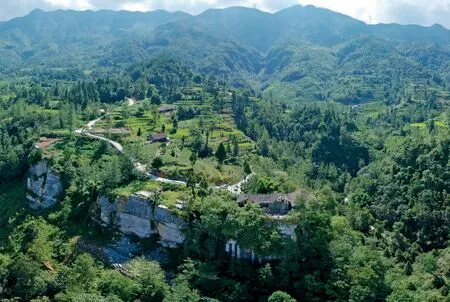

贵州省遵义市道真仡佬族苗族自治县三桥镇 Sanqiao Town in Daozhen Gelao and Miao Autonomous County, Zunyi, Guizhou Province(戴方睿摄影)

贵州省遵义市道真仡佬族苗族自治县三桥镇 Sanqiao Town in Daozhen Gelao and Miao Autonomous County, Zunyi, Guizhou Province(戴方睿摄影)

西南地区村落散居的传统至少可以追溯到汉唐时期①参见鲁西奇《散村与集村——传统中国的乡村聚落形态及其演变,《华中师范大学学报(人文社会科学版)》2013 年第4 期。,武隆山区西南缘道真县三桥镇的散村似乎都无法称之为聚落,一个个长屋和三合院散落在山间梯田之间,周围环绕以树木,是天工与人工的杰作。当地的百姓无法像晋东南的大家族那样把聚落建成城寨,但是借助喀斯特地貌形成的陡峭天险,矗立于崖壁的“土匪寨”成为抵御入侵的最后堡垒。

The tradition of dispersed village pattern in the Southwest region can be dated back to Han and Tang dynasties (Lu, 2013). In Sanqiao Town on the southwestern edge of Wulong Mountain famous for its Karst topography, the dispersed dwellings can hardly be considered settlements. Single buildings and courtyards are distributed among the terraces, surrounded by trees. It is a masterpiece created by both humans and nature. The local people here were not able to build their settlements into fortresses like the prominent families in Southeast Shanxi. Yet, by making use of the Karst topography, they built buildings on the cliffs to defend against invasions.

浙江省金华市义乌市雅治街村翰林第与水塘 The Hanlin Residence and its water pond in Yazhijie Village in Yiwu, Jinhua, Zhejiang Province(戴方睿摄影)

浙江省金华市义乌市乔亭村 Qiaoting Village in Yiwu, Jinhua, Zhejiang Province(戴方睿摄影)

中国东南地区的宗族村落里,绝大多数水塘是既非仪式性也非防御性的社会空间。在金衢盆地的风土聚落中,水塘与合院相伴而生,形成一种特殊的文化现象。即使在航拍照片中,从义乌雅治街村翰林第边水塘里各种深入水中的平台,也可以想见街坊邻居在这里一边洗衣服一边聊天的情境。而像翰林第那样以立柱架于水上的“水阁”,在明代民间营造类书籍《鲁班经》中就有记载。与雅治街相隔不远的乔亭村,不规则的椭圆形水塘中也有水阁,其另一侧因为后来建造的文化剧院,而给它带来了一点点仪式性色彩。

In the lineage villages of Southeast China, most of the ponds are social space which is neither ritual nor defensive. In the vernacular settlements of the Jinqu Basin, ponds and courtyards accompany each other, forming a unique cultural phenomenon. Even from the drone image, one could imagine neighbours chatting with each other while doing laundry on the platforms that extend into the pond next to the Hanlin Residence in Yazhijie Village. The ‘water pavilion’ at the Hanlin Residence, supported by columns over the pond, was recorded in theLuban Jing①Also known as the Canon of Luban, it is a local historical book about vernacular buildings, furniture, handicraft industry and technology of tool making from Ming Dynasty (second half of the fifteenth century).. In Qiaoting Village, not far from Yazhijie Village, there is also a water pavilion next to the pond. On the other side of the pond a cultural theatre built in the mid-20th century brings a slight sense of formality to the pond.

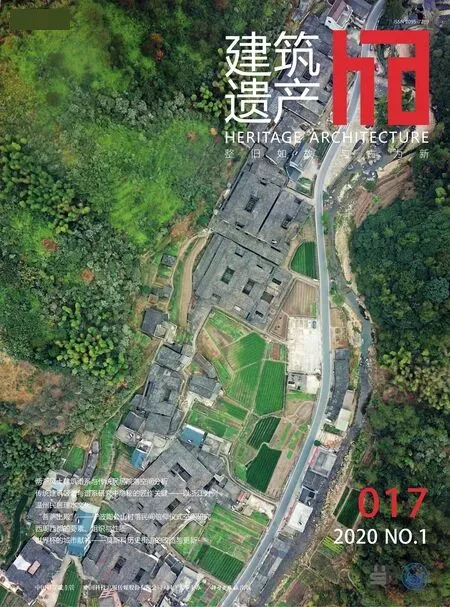

浙江省金华市东阳市紫微山民居:全国重点文物保护单位 Vernacular dwellings in Ziwei Mountain, Dongyang, Jinhua, Zhejiang Province, listed as National PCHS(戴方睿摄影)

当水塘与纪念性的轴线结合的时候,原本非仪式性的社会空间也会具有强烈的仪式感。浙江东阳紫微山许宅的风水格局将水塘的这种仪式感发挥到了极致。号称“三世尚书”的昭仁许氏规划建造紫微山民居群,门前水塘的土方运到宅后堆出小山,山上植木为林,造就了巧夺天工的风水格局。航拍无人机技术为现代人提供了“上帝视角”,使得我们能够将当年那位兵部尚书对自己家园的想象尽收眼底。

When a pond is combined with the monumental axis, this initially informal social space can also embody a strong sense of formality. The layout of the Xu Family Mansion in Ziweishan Village, Dongyang is an extraordinary example. The Xu family planned and designed this vernacular village. The mud from digging out the pond was used to create a mound at the back of the mansion. Trees were planted on it to enhance the axis. Drone technology has provided the ‘cosmic’ for modern people, which enables us to appreciate the entirety of this ancient family’s imagination for their own home.

浙江省金华市东阳市卢宅古建筑群:全国重点文物保护单位 The historic architectural ensemble of the Lu Family Mansion, Dongyang, Jinhua, Zhejiang Province, listed as National PCHS(戴方睿摄影)

提到轴线与格局,不得不提到东阳卢宅。如此恢宏的规模和严整的轴线往往使得人们忘记了卢宅曾经也是古村落的身份。肃雍堂以其超出普通民居的纪念性形式和纵深轴线对整个村落布局和朝向起到主导作用,使得村落的形态整体笼罩在其规则的强力控制之下。村落外围原有的环濠,不仅为这庄严宏大的聚落增添了一笔自由灵动的曲线,而且即使在今天,突降暴雨之时,这条水系依然可以起到排洪的作用。

When it comes to the axis and layout, the Lu Family Mansion in Dongyang must be mentioned. The magnificent scale and multiple axes often lead one to forget that the complex was once also an ancient village. Yongsu Hall, with its monumental axis beyond the status of an ordinary dwelling, is determining the layout and orientation of the entire village. The formal organisation of the village is under Yongsu Hall’s regulating order. The moat outlining the boundary of the village not only adds flexibility to the solemn settlement but also functions as a flood relieve mechanism till today.

浙江省金华市浦江县潘周家村:中国传统村落 Panzhoujia Village of Pujiang County, Jinhua, Zhejiang Province, listed as China’s Traditional Village(戴方睿摄影)

浙江省金华市义乌市田心村,浙江省历史文化名村 Tianxin Village of Yiwu, Jinhua, Zhejiang Province, listed as Zhejiang Province Historical and Cultural Village(戴方睿摄影)

即使同在一个地理单元,村落的宗族组织形态和民居建造方式都大体一致,每一个村落的微观肌理也有不同的选择。比如构成村落细胞的院落,金衢盆地北缘的潘周家村(上)以十三间头、十八间头及其衍生的多重多进组合院落为骨干,两大家族大型合院的朝向彼此垂直又各自统一。但与之相距不远的田心村,多数房屋则为小型的七间头天井院,使村落肌理呈现出完全不同的尺度感。田心村的环溪王氏同根同族,但是建筑朝向各异,在大地上绘制了一副构成主义作品。

Even within the same geographical unit, with similar lineage organisation and vernacular construction pedigree, each village presents various choices for its microscopic texture. Panzhoujia Village on the northern edge of Jinqu Basin is formed with large courtyards. The two largest courtyard complexes of the two lineages are perpendicular to each other yet forming their spatial orders. However, the nearby Tianxin Villages consists mostly of dwellings with small sky-well yards, which creates a spatial texture with a different dimension. Families in Tianxin Village are all branches of the same lineage, yet their courtyards take on various orientations, forming a constructivism artwork on earth.

浙江省丽水市松阳县石仓古民居,中国传统村落 Shicang ancient dwellings, Songyang County, Lishui, Zhejiang Province, listed as China’s Traditional Village(刘涤宇摄影)

翻过仙霞岭,来到瓯江上游的丽水市松阳县,石仓源位于深山中的河谷地段,包括茶排、后宅、蔡宅等若干村落。现在居住的大部分居民为清康熙年间从福建汀州府陆续迁徙过来的客家人,300 余年过去了,他们仍然说着自己的方言,并保留着客家习俗。从1790年开始,仅仅50 多年时间,洗砂炼铁发家的阙氏宗族在土地最肥沃的河谷地带留下了数十座大屋,透露出当年强大的财力和对环境的控制力。

Over Xianxia Mountain is Songyang County of Lishui, upstream of Oujiang River. Shicangyuan region is in the valley of the mountains, including Chapai, Houzhai, Caizhai, and other villages. Most of the current residents there are descendants of Hakka migrants who gradually moved from Tingzhou of Fujian Province during the reign of Kangxi Emperor of Qing Dynasty (1661–1722). Almost 300 years later, they are still speaking their dialect and retaining Hakka customs. From 1790, within over five decades, the Que Family, who operated metallurgy industry, built up a few dozen mansions in the most fertile river basin, testifying to the formidable wealth and human control over the environment of the old times.

浙江省丽水市松阳县山头村 Shantou Village of Songyang County, Lishui, Zhejiang Province (Photo credit: Dai Fangrui)(戴方睿摄影)

就在距离石仓源阙氏聚落不远处的山坡上,更早聚居于此的畲族聚落表现出更加自然且合理的形态。体量小巧的天井院沿着等高线嵌入山体,层叠的梯田和夯土墙融为一体。相比之下,阙氏大屋就像天外来客。的确,大屋的木构明显受到浙中地区的影响,但各院落多围绕最核心的院落布局,所呈现出的明显向心性既不同于浙中的“十三间头”又与当地的土著聚落迥异。

On the slope not far from the Que Family settlement, the earlier settlement of the She people presents more natural and reasonable formal features. Sky-well courtyards of a small scale are embedded into the mountain along the contour lines, with terraces and rammed-earth walls merging into each other. In comparison, the Que Family mansions look like aliens. Indeed, the timber structure of the mansions is influenced by the craft in central Zhejiang. Although the apparent centripetal tendency of the layout where several courtyards surrounding the core courtyard is different from both the ‘thirteen-room courtyard’ feature from central Zhejiang and that of the indigenous vernacular settlements.

浙江省丽水市松阳县石仓古民居:中国传统村落 Shicang ancient dwellings of Songyang County, Lishui, Zhejiang Province, listed as China’s Traditional Village(刘涤宇摄影)

浙江省丽水市松阳县石仓古民居:中国传统村落 Shicang ancient dwellings of Songyang County, Lishui, Zhejiang Province, listed as China’s Traditional Village(戴方睿摄影)

在石仓源茶排村河流的自由曲线和山上茶园梯田的跌落形态中,继善堂的体量和突出的几何形明确而醒目。村里保存了大量契约文书,反映了几百年来土地、房屋和日常生活变迁的情况,DnA 建筑事务所设计的石仓契约博物馆为这些文书提供了展示的场所。博物馆选址在继善堂旁边,但并没有试图与当地的大屋产生形态上的关联,而是从整体景观出发,将自身定位为跌落梯田的最底层一级,并以干砌石墙回应当地的挡土墙景观要素,使之呈现为地景的延伸。

In Chapai Village of Shicangyuan, among the terraced landscape, the formal volume and geometry of Jishan Hall stand out clearly. Historic indentures from the last hundreds of years are still preserved in the village, testifying to the exchanges of land and houses, and the evolution of everyday life over the centuries. The Shicang Hakka Indenture Museum, designed by DnA architecture studio, provides an exhibition space for these historic documents. The museum is next to Jishan Hall, yet it has not tried to associate with the local houses in the formal aspects. It sets itself in the local landscape and morphs into the lowest step of the terrace. The coarsely hewn stones layered in a wild lattice creates a conversation with the local element of the retaining walls and a continuation of the terraced landscape.

福建省漳州市华安县大地村:世界文化遗产地 Dadi Village of Hua’an County, Zhangzhou, Fujian Province, inscribed as a World Heritage site(戴方睿摄影)

福建省大田县万宅村绍恢堡:全国重点文物保护单位 Shaohui Fortress in Wanzhai Village, Datian County, Fujian Province, listed as National PCHS(戴方睿摄影)

建筑体量与形态反差最大的当属福建土楼,鲜明的几何形与超常的体量感在高空航拍时尤其强烈。福建华安大地村的二宜楼与远处的南洋楼,伫立在戴云山区典型大厝民居的拱卫之中。

大田县万宅村绍恢堡的几何形更多来自其采用的防御系统,尤其是土堡后部环形的跑马道。而其核心部分却是以厅堂和护厝构成的院落式布局。回到地面上,只有进入土堡的后部才能感知到环形跑马道的的整体性,中部的合院空间感受与当地其他类型的大厝基本一致。空中读村的整体性与置身场地所感知到的复杂性之间若有微妙互动,便是进一步深入认知的开始。

Fujian’stulouhouses illustrate the most considerable contrast between its architectural volume and form. The definite geometric shape and extraordinary volume can be sensed intensely from aerial photography. The Eryi House and the Nanyang House in Dadi Village are surrounded by the vernacular dwellings typical in Daiyun Mountain area.

A different geometric form and spatial organisation of the Shaohui Fortress in Wanzhai Village is mainly due to the defensive system they use, specifically the circular horse runway at the back of the compound. However, the core of the fortress is the combination of halls and side wings. The experience in it is similar to typical dwellings around in the area. The subtle interactions between recognising the overall entirety from the air and the complexity experienced on-site are the beginning of a deeper comprehension of vernacular architecture in China.