Modified percutaneous transhepatic papillary balloon dilation for patients with refractory hepatolithiasis

Bin Liu, Pi-Kun Cao, Yong-Zheng Wang, Wu-Jie Wang, Shi-Lin Tian, Yancu Hertzanu, Yu-Liang Li

Abstract

Key words: Intrahepatic cholestasis; Sphincter of Oddi; Dilation; Common bile duct; Percutaneous; Balloon

INTRODUCTION

Hepatolithiasis is defined as the presence of gall stones in the bile duct peripheral to the confluence of the right and left hepatic duct. It is a benign disease, but with a poor prognosis due to possible complications including recurrent intrahepatic stones, secondary common bile duct (CBD) stones, biliary strictures, recurrent cholangitis, biliary cirrhosis, liver atrophy, and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma[1,2].

Hepatolithiasis is present with the coexistence of choledocholithiasis or cholecystolithiasis in 70% of patients. This disease is prevalent in Eastern Asia[3-7], but rare in Western countries[8]. However, population migration has resulted in the increased prevalence in the West[9]. Several factors are related to hepatolithiasis including parasitic infestation[10], bacterial infection[11], bile stasis, diet and anatomy[12].

As one of the most complex cholelithiasis, the treatment is complicated and difficult requiring a team including interventional radiologist, gastroenterologist and surgeons, and has improved due to advanced technologies. The combined approach is percutaneous, endoscopic, and surgical[13].

Based on our previous experience, for certain groups of elderly patients suffering from CBD stones with previous gastrointestinal surgery, gastrointestinal anatomical abnormalities, esophageal and gastric varices, severe cardiac or pulmonary comorbidities, endoscopic procedures or surgery may be difficult to perform, and percutaneous transhepatic papillary balloon dilation (PTPBD) could be an alternative[14,15]. We evaluated the clinical efficacy and safety of a modified PTPBD for the removal of intrahepatic bile duct stones in patients with severe comorbidities, especially when endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP) was not successful.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

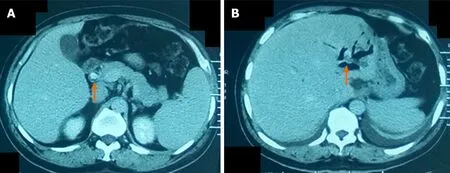

From February 2014 to June 2015, 21 patients admitted with hepatolithiasis (16 cases with concomitant CBD stones) diagnosed by ultrasonography, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) (Figure 1) were enrolled and underwent modified PTPBD. This retrospective study was approved by the ethics committee and all patients provided written informed consent.

Laboratory values, including white blood cell (WBC) count, total bilirubin (TBIL), direct bilirubin (DBIL), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), albumin (ALB), and amylase were obtained using routine laboratory tests.

Inclusion criteria included: (1) Intrahepatic stones in the right or left hepatic duct with symptoms of obstructive jaundice, pain, or fever; (2) Intolerance of endotracheal anesthesia; (3) Inability to tolerate or refuse to undergo open surgical, laparoscopic, or cholangioscopic procedures; (4) Predicted life span ≥ 1 year; and (5) Karnofsky score > 70.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) Concomitant CBD stone with a diameter > 20 mm; (2) Four or more intrahepatic stones; (3) Severe cardiac insufficiency (New York Heart Association class III-IV) or advanced lung disease (determined by consultation with respiratory disease specialists), liver disease (Child-Pugh class C), or advanced renal dysfunction (stage G3 to G5 of chronic kidney disease); and (4) Severe coagulopathy (prothrombin time > 17 s and/or platelet count ≤ 60 × 109/L).

Procedure: Modified PTPBD

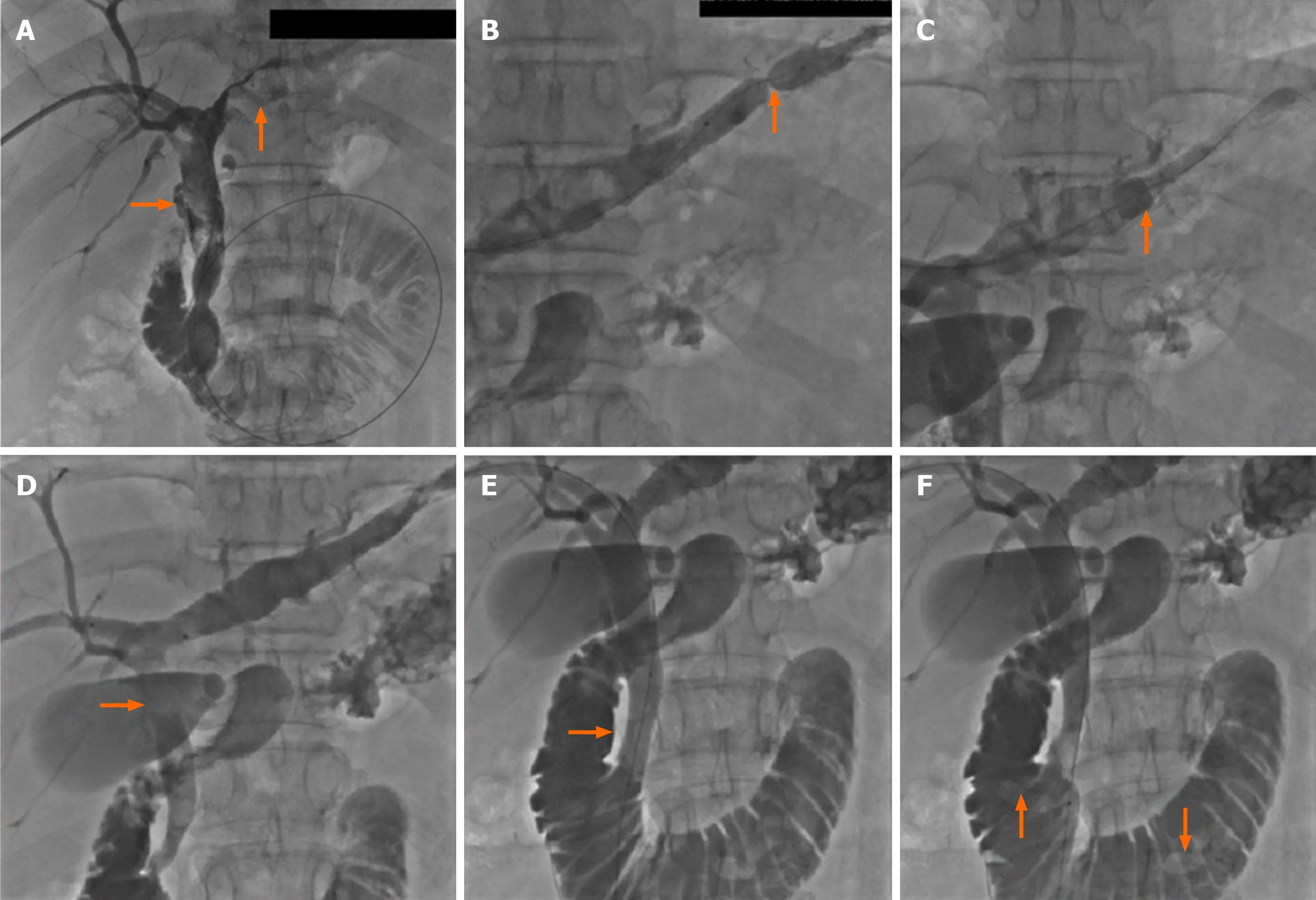

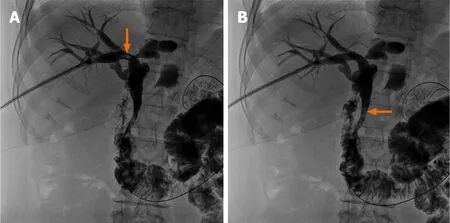

All procedures were performed with intravenous anesthesia. The intrahepatic bile duct (usually right) was punctured under ultrasonic sound and fluoroscopic guidance. Cholangiography with diluted contrast media delineated biliary duct anatomy and revealed the location, number and size of the bile duct stones (Figure 2A). An 8- to 14-French introducer sheath was inserted into the punctured branch, and then a 150-cmlong guidewire was advanced into the intrahepatic bile duct branch peripheral to the stones, with the help of a 5-French tapered-angle angiographic catheter. A stiff 260-cmlong guidewire was exchanged into the bile duct. Affected bile duct was dilated with a balloon (Advance 35LP; Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, United States) if stenosis was present (Figure 2B). A Fogarty catheter (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, United States) was introduced along the guidewire, crossing the stones into the peripheral bile duct branch. The balloon was inflated and stones were pushed into CBD (Figure 2C and D). For large stones, basket mechanical lithotripsy was used to reduce the stone size. For stones located in the punctured bile duct with no or moderate stenosis, injection of saline through the sheath or a moderately inflated balloon dilation catheter was used to push the stones into the CBD (Figure 3A and B).

Stones in CBD should be managed according to the procedure, which has been described in our previous publications[14,15]. The papilla was gradually and intermittently dilated until the balloon’s “waist” disappeared (Figure 2E). The inflation process took 30 to 60 s and the dilation was repeated 3 to 4 times for each patient[10,11]. The balloon size depended on the diameter of the dilated CBD and largest stone, and ranged from 10 to 20 mm. After sphincter dilatation, stones were pushed into the duodenum through the dilated papilla (Figure 2F). After the procedure, the stools of each patient were checked for 1 wk to collect the stones. Stone number and sizes were estimated according to imaging modalities and stools. After 1 wk, cholangiography was performed to exclude residual stone. PTPBD was performed again if there were residual stones. If not, the drainage catheter was withdrawn.

Follow-up

Recorded outcomes included success rate, procedure time, hospital stay, causes of failure, and procedure-related complications. The levels of WBC count, TBIL, DBIL, AST and serum amylase were recorded before the procedure, at 1 wk, and at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, and 24 mo after the procedure. Imaging modalities such as ultrasound (preferred examination), CT, or MRCP were repeated during follow-up every 3 mo. Biliary duct infection, hemorrhage, pancreatitis, and gastrointestinal and biliary duct perforation, considered as short-term complications, were assessed before discharge. Long-term complications such as reflux cholangitis and calculi recurrence were recorded for 2 years.

Statistical analysis

Figure 1 A 58-yr-old man with common bile duct stone and intrahepatic bile duct stone. A: Computed tomography after contrast administration of the common bile duct stone (arrow); B: Computed tomography without contrast of the intrahepatic bile duct stone (arrow).

Figure 2 Cholangiography. A: Cholangiography revealed the location, size, and number of the intrahepatic and common bile duct stones; B: The left bile duct with stones was dilated with a balloon catheter in presence of stenosis; C: The intrahepatic bile duct stone was pushed with a dilated Fogarty catheter; D: Stone was pushed into common bile duct; E: The papilla was dilated; F: Stones in the common bile duct were pushed into the duodenum.

Continuous variables with normal distribution are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and analyzed with the Student’st-test. Continuous variables with unnormal distribution were expressed as the median and interquartile range, and analyzed with the rank sum test. Categorical variables were presented as number and percentage, and analyzed using theχ2test. All data were analyzed with SPSS version 24.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).P< 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

There were 11 men and 10 women aged 51 to 82 (mean, 68.3 ± 4.2) years. Eleven patients (52.4%) with concomitant intrahepatic and CBD stones were admitted with obstructive jaundice. Six patients (28.6%) suffered from intermittent fever and four patients (19%) from abdominal pain. All cases were diagnosed with cardiac or pulmonary diseases including pulmonary emphysema, respiratory insufficiency, coronary heart disease, and cardiac insufficiency.

Figure 3 For stones located in the punctured bile duct with no or moderate stenosis, injection of saline through the sheath or a moderately inflated balloon dilation catheter was used to push the stones into common bile duct. A: A stone (arrow) located in the right hepatic bile duct; B: Saline was injected through the sheath and the stone was pushed into the common bile duct (arrow).

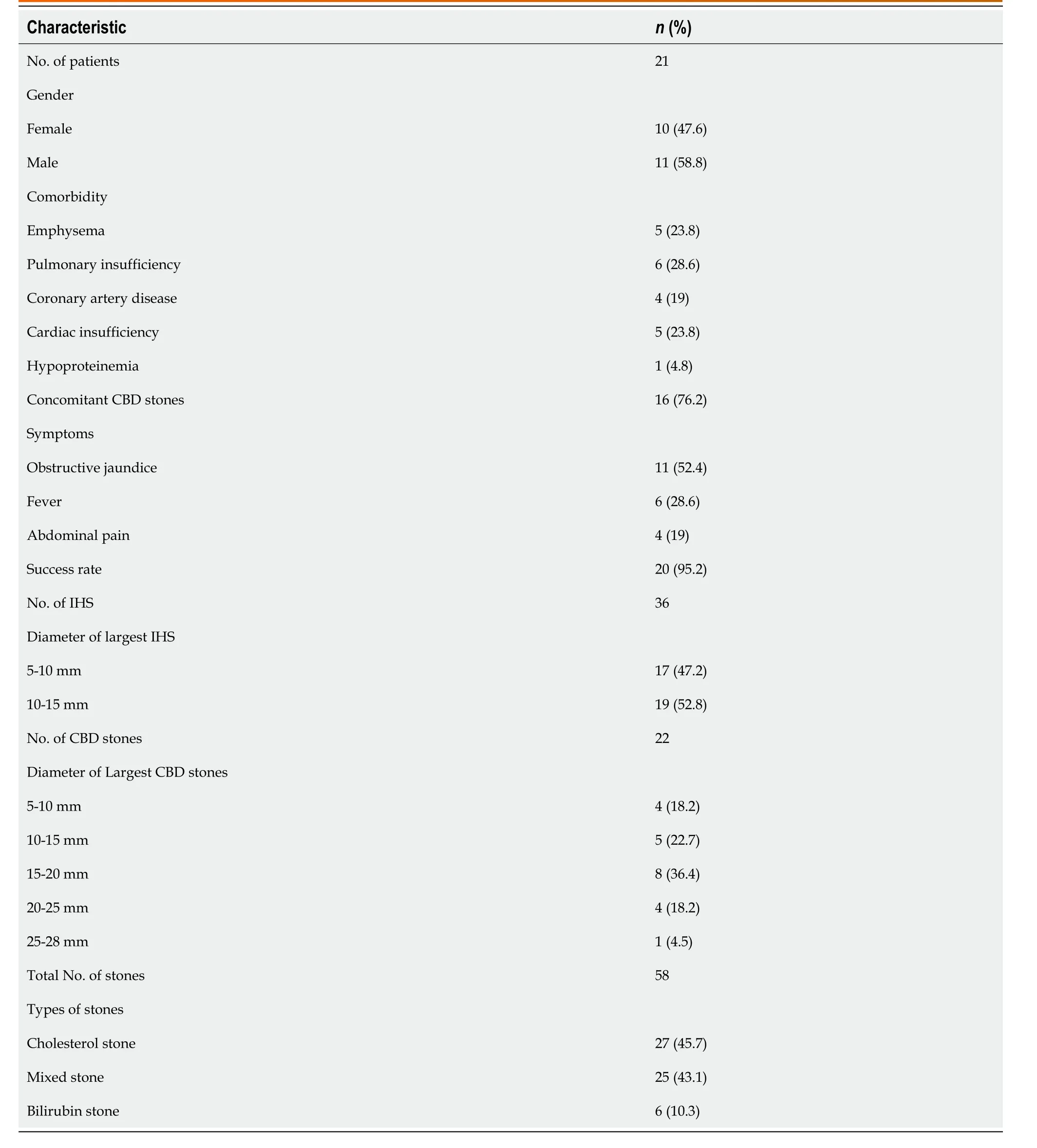

The mean age of the 21 patients was 68.3 ± 4.2 years old. A total of 36 intrahepatic stones were successfully expelled into the duodenum by modified PTPBD in 20 (95.23%) patients. The diameters of intrahepatic stones ranged from 5 to 15 mm. The diameter of 17 (47.22%) stones was < 10 mm and 19 (52.78%) ranged from 10 to 15 mm. Concomitant CBD stones were present in 16 patients, with stone size between 5 to 20 mm. Characteristics of patients and treatments are summarized in Table 1. Mean procedure time was 65.8 ± 5.3 min. PTPBD was repeated in one patient due to residual stones. Mean hospitalization was 10.7 ± 1.5 d.

The procedure failed in one patient because of stone impaction in the intrahepatic bile duct. The inflated Fogarty catheter could not push the stone into the CBD. The patient was transferred to the Department of General Surgery and underwent percutaneous transhepatic cholangioscopy.

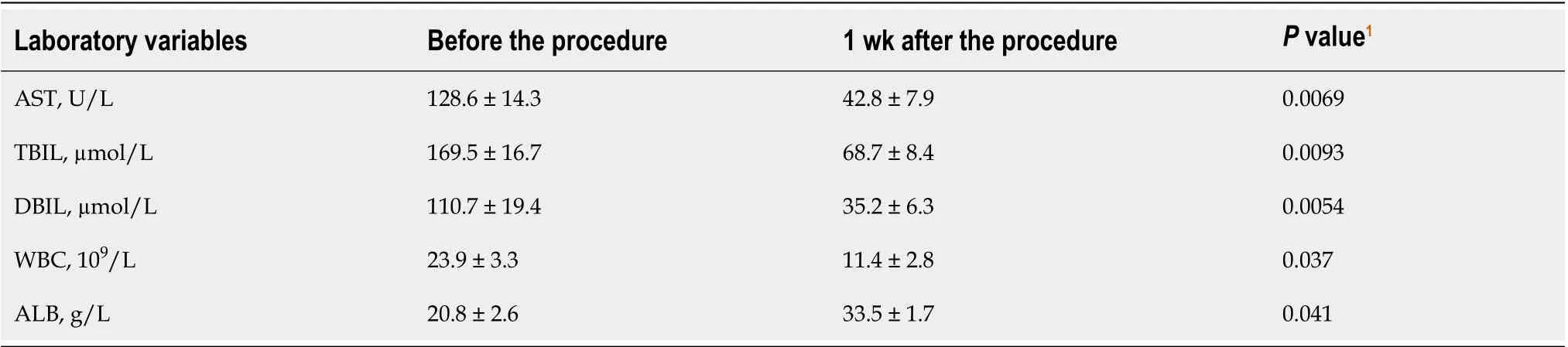

Abdominal pain was common during papillary dilation but was relieved immediately after the procedure. The symptoms of jaundice disappeared after the procedure in all patients. WBC count, TBIL, DBIL, and AST declined markedly after the procedure. The differences in these indexes before and 1 wk after the procedure were significant. In contrast, ALB concentration significantly increased after the procedure (Table 2).

Fever and chills suggesting biliary duct infection, occurred in 2 patients (9.52%), and subsided after antibiotic therapy for 2 to 3 d. Mild elevated serum amylase was seen in one patient (4.76%), without sign of peritoneal irritation or fever and decreased to normal levels in 2 d after procedure. We considered it a minimal subclinical reaction and not true pancreatitis. No sign of gastrointestinal or biliary duct perforation were present. All patients were followed up for 2 years, and there was no evidence of reflux cholangitis and calculi recurrence.

DISCUSSION

Vachellet al[16]first reported intrahepatic calculi in 1906. The incidence was reported to be 20%-30% of all patients undergoing surgery for gallstone disease. Most patients are affected in the 3rdto 7thdecades on life with equal gender distribution. Concomitant intrahepatic and extrahepatic stones are found in approximately 70% of all hepatolithiasis cases[7,17].

Hepatolithiasis is characterized by recurrent pyogenic cholangitis with inflammatory bile duct wall leading to progressive biliary stricture, causing bile stasis, liver atrophy, and cholangiocarcinoma[18]. In China, 80% of patients with peripheral intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma have associated intrahepatic stones[19,20].

The aims of treatment are prevention of liver damage by elimination of stones and recovery of bile fluidity and includes stone clearance, recovery of bile duct stricture, and providing good drainage of bile[21-23]. Surgical options are considered by many authors the preferred treatment. However, the surgical procedure has significant morbidity and mortality. ERCP is used for papillotomy, sphincterotomy and retrievalbasket for stone extraction, which should be considered the first attempt to treat hepatolithiasis. The application is limited because large or impacted stones could not be easily managed by conventional endoscopy. Brewer Gutierrezet al[24]reported peroral cholangioscopy with the development of flexible, high-resolution endoscopes have enabled successful endoscopic therapy in laser and electrohydraulic treatment in > 85% of patients. However, such a procedure cannot be performed in most hospitals in China due to the lack of access to cholangioscopy. In addition, for patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomies, the endoscopic procedure could be very difficult. Endoluminal approach with intraductal lithotripsy combined with extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy may remove stones in approximately 66% of patients.

Table 1 Patient and treatment characteristics

Table 2 Relevant variables before and 1 wk after the procedure

Percutaneous options provide biliary drainage, with transhepatic placement of catheters, stents, basket/balloon catheters and cholangiography to detect or confirm clearance of biliary stones. Percutaneous approach is advantageous for high-surgicalrisk patients with altered gastrointestinal anatomies, multiple stones in several segments or patients rejected to undergo surgery.

Furthermore, patients with cardiac or pulmonary comorbidities may not tolerate endotracheal anesthesia and surgery. Therefore, modified PTPBD under intravenous anesthesia has advantages and such patients may benefit from this procedure.

In 2000, Shiraiet al[25]reported that PTPBD could relieve obstructive jaundice caused by CBD stones. To the best of our knowledge, our team performed the first PTPBD procedure to treat CBD in China in 2008[26]. Compared with ERCP, the inflated balloon dilates the entire papilla but keeps the whole structure intact[27], with low incidences of biliary duct infection and hemorrhage and no pancreatitis or perforation of the gastrointestinal or biliary duct[26].

The first step for hepatolithiasis is to move the stones into CBD. A Fogarty balloon catheter is useful for small stones, while a mechanical basket crashes and reduces the size of large stones. The presence of bile duct stenosis has been considered a cause of lithogenesis and stone recurrence. Bile stenosis is also a major factor in hepatic atrophy and cholangiocarcinoma developing[28]. Therefore, balloon dilation is necessary when bile duct stenosis is present.

Simultaneous CBD stones are not contraindications. However, the size of CBD stones should be limited. Endoscopic treatments, including endoscopic sphincterotomy and endoscopic papillary balloon dilation, usually consider stones with a diameter exceeding 10 mm to 12 mm as large stones[28,29]. For these difficult cases, percutaneous approach with a large balloon (≥ 10mm) and long-term dilation could be safer, and the short procedure time remarkably decreased the incidence of pancreatitis. This is a significant advantage and was verified in our clinical practice and in previous studies of PTPBD[14,15,25,26]. The maximum balloon diameter we used in this study was 20 mm and no pancreatitis occurred after the procedure (unpublished data). Hence, the maximum diameter of CBD stones was determined to be no larger than 20 mm in this study.

As in endoscopic procedures, multiple stones are challenging in PTPBD. Repeated procedure may damage mucosa, causing bleeding and local edema, while an extended procedure time may increase the cardiopulmonary morbidities and anesthetic risk. Based on the current experience of our team, PTPBD should not be attempted if there are four or more stones.

Nevertheless, this study had two limitations. First, as a pilot study, the number of patients was small, and this method is devised for a specific subset of patients in one center. Second, the retrospective character of the study may have caused a selection bias of cases.

In conclusion, our results indicate that modified PTPBD is a safe, feasible, and effective treatment option for intrahepatic bile duct stones. It is a new alternative procedure for a small number of patients with hepatolithiasis and may be a treatment option in patients with severe comorbidities or in patients in which ERCP was not successful. A prospective study in multiple centers and the generalizability of our findings to the broader population will be investigated in the future.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

The treatment of hepatolithiasis is complicated and difficult. Some patients cannot tolerate surgery due to severe cardiac or pulmonary comorbidities, or cannot be treated with endoscopy because of altered gastrointestinal anatomies.

Research motivation

Our previous experience indicated percutaneous transhepatic papillary balloon dilation (PTPBD) could be an alternative for common bile duct stones.

Research objectives

In this retrospective study, the clinical efficacy and safety of modified PTPBD were assessed for the removal of intrahepatic bile duct stones in patients with cardiopulmonary comorbidities or altered gastrointestinal anatomies.

Research methods

Twenty-one patients with intrahepatic bile duct stones who underwent modified PTPBD were enrolled in this study. Outcomes, including success rate, cause of failure, complications, procedure time and hospital stay, were analyzed. Reflux cholangitis and calculi recurrence were recorded for 2 years.

Research results

The success rate was 95.23%. No pancreatitis or perforation occurred. No evidence of reflux cholangitis and calculi recurrence were observed for 2 years.

Research conclusions

Modified PTPBD could be considered as a safe, feasible, and effective treatment option for intrahepatic bile duct stones in patients with cardiopulmonary comorbidities or altered gastrointestinal anatomies.

Research perspectives

Multi-center prospective study should be conducted to compare modified PTPBD to surgery or endoscopic procedures to gain more evidence.

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年27期

World Journal of Gastroenterology2020年27期

- World Journal of Gastroenterology的其它文章

- Histopathological landscape of rare oesophageal neoplasms

- Details determining the success in establishing a mouse orthotopic liver transplantation model

- Serum ceruloplasmin can predict liver fibrosis in hepatitis B virusinfected patients

- Acceptance on colorectal cancer screening upper age limit in South Korea

- Transarterial chemoembolization with hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy plus S-1 for hepatocellular carcinoma

- Intestinal NK/T cell lymphoma: A case report