Saussure’s Prolegomena—Toward a Semiotics of the Mind

Per Aage Brandt (1944 - 2021)

Abstract

Keywords: word-based linguistics, mental architecture, cognitive semiotics, sign categories

... it is a system of signs where the only thing that is essential is the union of meaning and acoustic image, and where these two parts of the sign are equally psychological. (CLG,1962, chap. III, §2, 3o, p. 32)

1. Word versus Sentence

When Ferdinand de Saussure, in his general linguistics project (1906-1911) behind CLG, defines the notion oflangue—that is, ofalanguage, as opposed to language in general—he refers to the unit he calls thesign. A language, such as French or Kiswahili, is defined as asystemofsigns. What is meant by the termsystemhere is not an easy guess; he could mean a paradigm of all morphological paradigms in a language, or he could mean a list of all compatible elements in all possible utterances,or he could mean some sort of grammar of all possible constructions. Neither of these options make clear what a Saussurean system is or how to explore it. By contrast, what is clear is that the sign in question is theword. It follows from the distinction Saussure makes betweenlangueandparole, speech, that the sentence is not his defining sign,since sentences,lesénoncésou les phrases, are units in individual speech rather than in the social system oflangue. This is in fact the radical difference between the two main traditions in modern linguistics discussed in de Mauro (1972), the European tradition initiated by Saussure and critically continued by Louis Hjelmslev1, and the Anglo-American tradition most often exemplified by Leonard Bloomfield and his critic, Noam Chomsky. Saussure thinks of languages as institutions ofwords,somehow systematized, whereas the Anglo-American structuralism basically thinks of them in terms ofsentencesand their somehow specified sentence syntax.2

This distinction is capital. Aword-basedlinguisticsdevelops strong phonetic research and a marked interest in semantics, and it focuses on etymologies and dictionaries, continuing the traditions of philology. Asentence-basedlinguisticsof course foregrounds grammar and pragmatics; it attends to the study of dialects,sociolects, sexolects, etc. and conversational phenomena, including speech acts.The Saussurean formalisms of the European continent, from Roman Jakobson and Claude Lévi-Strauss3to Algirdas-Julien Greimas’ structural semantics and modern French semiotics, where a certain affinity to discourse-oriented structuralism and post-structuralism is notable, are an ocean away from generative syntax and modern cognitive semantics and construction grammars, even if the term “structuralism” can be found on both sides of the ocean.

This curious fact has inhibited and weakened most attempts at formulating a general theory of language as a solid base for a rigorous science of language, orSprachwissenschaft. Linguistics is therefore still a tentative collection of disciplines lacking the unity or homogeneity that Saussure claimed, and which Hjelmslev’s glossematics still dreamed of placing under the concept of immanence, orstructure immanente.

There is not even a reliable consensus as to the definition of words and sentences,since it would depend on a unifying theory, which is non-existent. Daily life, however,does not need definitions of this type. The term “word” exists in all known languages,as a natural kind that obtains phenomenological reality through language acquisition.All speakers can exemplify it. The same of course goes for the term “sentence”, in so far as we all know what it is to be interrupted before we complete one; sentences need completion, but dialogue easily and frequently frustrates this need.

Words and sentences are not organized the same way, and there is no known successful way to reduce one of them to the other, or to integrate them in one“system”.4There might be a deep and evolutionary reason for this dilemma; words may serve the human mind in other respects than do the sentences we fill with words.The integration of words in sentences indeed happens inspeech, as Saussure insisted,not in a linguistic system; otherwise, we would speak like an axiomatic system.

2. Thought, Signs, Words

Semiotics inheriting Saussure’s view of linguistics as a specialsemiologygenerally agree to consider words as minimal signs in language. They are biplanary5conceptual objects, composed bysignifiersin the expressive plane and bysignifiedsin the content plane, and their biplanary composition, where signifiers and signifieds are interdependent planes, as Saussure and Hjelmslev suggested, is conditioned by a certain principle ofsemiosis, which is situated in the historical archives of the social instance responsible for the sign emission. Whereas Saussureans consider the sign to beconceptuelin this sense, that is, social and psychological (psychique), C. S. Peirce’s followers are instead convinced that signs connectthings, not necessarily concepts,whenever they “stand for” each other—a notion that might help the logician connect to the world,in casua “symbolistic” world where things readily “stand for” other things, if considered logically; if certain things or states of affairs allow us to infer other things or states of affairs, then the logic of things, Peirce thought, is asemeiotic.Peircean “semiotics” is therefore constitutionally independent of any consideration of language and languages. It is propositional, to the extent that propositions represent states of affairs; and Peirce’s semeio-logic indeed includes pragmatic perspectives,just like sentence linguistics does.6

Saussure’s conception of the sign is instead psychological, that is, mental,hence his generic model of the sign is, in CLG, a diagram of connected entities in two mental, conceptual “planes” of which one iscontentdriven, while the other isexpressiondriven. The implication of Saussure’s “mentalism”, versus Peirce’s logical realism, is that the linguistic sign, and its planary structure, must be studied as a property of the human mind; on this point, we have to develop his ideas in the post-Saussurean modern context of cognitive science, the study ofminds. Minds in fact have to recognize something to be expected on each plane; on one hand, something like minimal bits of thinkable items, ideas, and on the other, concepts of minimal bits of sound shapes or hand gestures, separated and articulated within the time frames of perception and production, auditive or visual. Thetimeof conceiving the expressive items and thetimeof conceiving the intended bits of thought must thus be directly related—this is one of the important but unnoticed aspects of the mental,conceptual semioticsthat Saussure implicitly founded. Time of speaking and time of thinking-forspeech must be correlated; otherwise there would not be a linear chain of articulated words that speaker and hearer could share.

Again, the Saussurean signifier is a concept, and so is the Saussurean signified.However, why would these two concepts at all be related and made interdependent in the sign by a “semiosis”? Words are, arguably, symbols (not icons), and those are“arbitrary”, conventional and coded; so, how does the conventional and coded binding happen? How did it happen in human evolution? The post-Saussurean researcher will situate language in the line of human cultural evolution and allow herself to reopen the ontological question of origins that positivism had banned. Music may have preceded language in human cultural evolution. The origin of words may in fact precede that of sentences and may be traced back to early music, that is, to discrete vocalizations used for calling and naming, and then for singing and sharing social events.7This use of articulated sound acquires conceptual meaning as soon as specific expressions can both be recognized and produced, allowing producers to recognize their own expressions and control their shape and “well-formedness” in real time for being shared. The auto-controlled expression may then be deliberately chosen for a purpose and for an addressee, given theintentionalityof animal and human consciousness.8It induces the phenomenological possibility of thinking-to-someone, which means“cutting out” parts of thought, partitioning it into ideas, concepts, and “pointing to”them by the vocal gesture, accompanied by deictic gestures. Words may thus have served thought before they came to serve sentences. They may have invited us to develop reflexivity, the capacity to observe and monitor parts of our own thinking at a certain mental distance and to isolate and frame those parts. Reflexivity and mental distance in turn open a space-time in the mind, a “mental theatre”, as Descartes may have said.9The humanimaginarythus becomes accessible to voluntary inspection and even allows some deliberate editing. We can therefore, at least partly, choose what to think “about” and what to remember, hence learn. “Aboutness”, in John Searle’s sense, is born.

Aboutness, as in: “what are you talking about?”, is a matter of signifiable meaning and therefore about the Saussurean signifieds. Signifieds are concepts, and we generally think “about” them while combining them.Howdo we combine them? This post-Saussurean problem clearly concerns thinking, and referring to sentences (like:“we combine them by putting them into the same sentences”) would be unsatisfactory.The French mathematician and philosopher René Thom often remarked that to understand an algebraic formula, an equation, we must mentally set up atopologicalspace-time where the variables of the formula determine some shape; mentally“seeing” that shape is then to “understand” the formula. Understanding, following Thom, is inherently geometrical in this sense, not by virtue of finding a metrically determined, quantified mathematical geometry for all concepts but through the ability to spontaneously set up a pre-mathematical and plastic, qualitative geometry rooted in our inherently graphical imagination. Speech gestures are expressions of the sametopological imaginary, as are the abundant expressions in language of abstract spatial and spatiotemporal relations between concepts. Apart from language and gesture,thoughts are, according to this analysis, accessible to their thinkers as qualitative mental diagrams representing imaginary topologies.10The role of words in these diagrams is to single out and label instances, regions, boundaries, flows, bindings, and other categories that the “architecture” or mental graphics combine and connect. What these mental configurations do is to set up schemas and larger models of the problems that occupy the mind. When we then describe our imaginary setups and constructs,the sentences of language iconically approximate the structural properties of these diagrams; the syntax of phrases and sentences is morphologically prepared for precisely this function ofsimulating thought. Sentences are iconic in this sense. Hence words are in factreusedin syntax; their first use was topological, and then phrased language takes over their meaning, often still accompanied by expressed diagrams or speech gestures.

Topologies are mental diagrams or figurations that can be manifested as such,typically using alphanumerical indicators or words as labels. Here is an example from musicology, the great jazz musician and composer John Coltrane’s elaborate drawing of his interpretation of the circle of fifths (see Figure 1 below):It is believed that this diagram lays behind his very special harmonization in compositions such asGiant StepsandCount Down, where a sort of whole-tone modulation is used.11As can be observed, this circle consists of five repeated wholetone scales in two rings, one from C and the other from B. The fifths, C-G-D etc., of the ordinary circle of fifths will then appear if we jump counterclockwise between the two rings. InGiant Steps, Coltrane posits three equidistant tonal bases—B, G,and Eb—and modulates swiftly between them; they are found in the fifth segment of the inner ring; but they are still connected to the rest of the well-tempered system of fifths that allows modulation by dominants. In this way, Coltrane could mentally see,explore, and unfold what he may first have mentally and intuitively heard; and finally,he was then able to present a major contribution to modern jazz music by masterfully playing it as he “saw” and understood it.

Figure 1.

Diagrams always thus assist the mind in elaborating possible solutions to its problems. They are apparently symbolic, but they are uncoded, and are therefore not symbolic. They are apparently also iconic, if understood as pictures of some depicted item; but there is no depicted item here, so they are not iconic. Instead, diagrams constitute a semiotic category in its own right, neither symbolic nor iconic, which has hitherto escaped scholarly classification. Diagrams are, if I am right, fundamental creations of the thinking mind, and their prospective study will be fundamental in a semiotics of the mind, since these strange creations seem to be both the means by which the mind “talks” to itself and the most immediate means to communicate to other minds how and what it thinks. Expressed diagrams reflect the very same diagrams in the head of the person expressing them. We know this is the case with maps. Ifwords(or other alphanumerical signs) are used in the expressed diagram,they are repeated from the inner diagram.12

This extremely post-Saussurean view of course changes the premises for a semiotic discussion of the relation of language and thought. In a broader perspective it may even change our understanding of all semiotic functions in their relation to the mind; we will offer some suggestions in this direction at the end of this essay.

3. Language

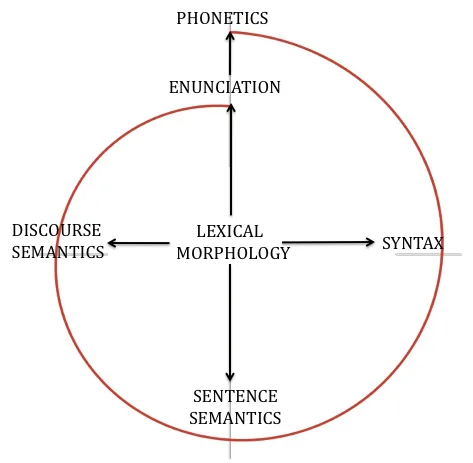

It thus seems impossible to conceive language in terms of a unitary Saussurean “system of signs”. If we want to diagram at least somehow an “architecture” of language, we must therefore, and on this point following Saussure, account for the special role of words, or the lexical “component”, inside and outside of language proper, phrased language. Words feed into sentence grammar, of course, by their syntactic functions;and they feed into sentence semantics by the meaning of their open and closed classes.They also refer to the domains where terminological networks form encyclopedic fields that inform discourse semantics. They furthermore contain indications of speaker/hearer status and viewpoint and other properties of subject-to-subject specification, pertaining to the component we call enunciation. Finally, words are phonetically articulated and, in written languages, graphically specified. In a sense,words therefore belong to all linguistic “components”; or rather, these instances in the architecture of language as such form a ring of co-active structuresaroundthe lexical instance, which feeds into them in all directions. This idea is shown in the following diagram (Figure 2 below):

Figure 2.

In reception, the heard sound shape of the lexical string determines a syntactic reading, which in turn creates a semantic whole, the “meaning of the sentence”;this creation is further inserted in a discursive frame of meaning, and this “piece of discourse” feed into the enunciative situation of communication. From here, the hearer possibly becomes the speaker, by jumping from enunciation topronunciation in a response to the content received. The jump is normally motivated by an instance of thinking, though; we will return to this issue shortly.

Discourse semanticsis the wider encyclopedic network that words are parts of.Production and reception of language activate the entire spiral of instances around the lexical instance. Switching between being represented as a first person and as a second person, in a dialogue, that is, between speaking and hearing, or writing and reading,corresponds to “jumping” betweenenunciationandphoneticor graphic performance,back and forth across the gap in the spiral.

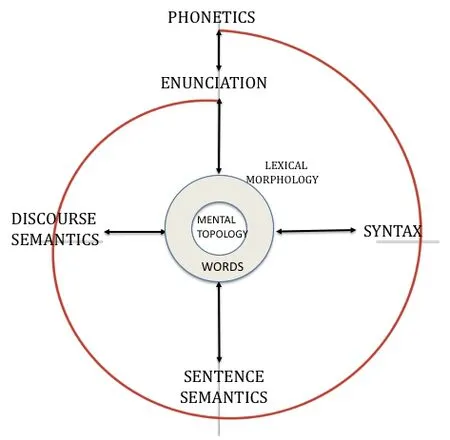

However, the double status of words must be represented, if we want a model including the consequence of the post-Saussurean insight outlined above.13I suggest imagining a space inside the lexical component giving access to the topological imaginary where words have direct indicative and labeling functions.14The diagram of language architecture would then look like this (see Figure 3 below):

Figure 3.

Language would be wrapped around thought in a lexical ring and then a spiral of interrelated components. In reception, language would have several parallel entries into thought, and while poetry needs attending to all of them, pragmatic prose would mainly just need the participant to attend to the discourse-semantic entry while neglecting sound-dependent information from enunciation (intonation)and phonetics (assonances). Rhetorical prose calls for attention both to syntax, to sentence semantics, and to discourse semantics. Poetry particularly calls attention to enunciation. Nevertheless, in our minds, all components will still work automatically and remain interdependent, as each other’s co-structures.

In this version, we may say that the linguistic sign, the word, has one signifier and in fact four signifieds15: a syntactic set of functions, a phrase-semantic set of possible meanings, a discourse-semantic set of network-determined meanings, and an enunciation-related set of meanings—and these sets will inter-determine each other when a word is determined to mean something specific in a given “context”, that is, in these semantic dimensions.

When we want to say something in some situation, we just need to target someone as our possible addressee, hence to set up an enunciative orientation, and this orientation will single out a discourse-semantic field covering things of our shared concern; then utterance-close sentence semantics will occur, triggering each time a couple of syntactic constructions, which we linearize to present phonetic strings under an intonation monitored by the initial enunciative attitude—and we talk. Generally,we do not need to pay attention to these processes themselves, but if we try to perform in a foreign language, or if the dialogue is expected to be difficult for some emotional reason, it is likely that some of the instances, for example syntax in an official letter,will become conscious and even call for our careful crafting, and need some special attention.

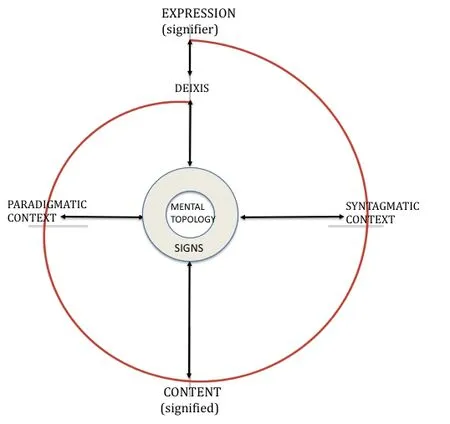

Saussure’s idea that since words are signs, other signs should be understood in the same way, and linguistics should hence be part of a generalsemiology, may be restated in our new terms. The spiral will no longer be reserved for the extensive structural potentials of words but will include the structural unfolding of all other signs that can be expressed. Like in the case of words, the meaning values of other signs would be determined semantically by their mutual affinities, differences and oppositions, and their possible combinations. The spiral of properties characteristic of language would become a set of structural circumstances pertaining to all expressive phenomena, and we could apply Roman Jakobson’s suggestion (or diagram) of the crossingparadigmaticandsyntagmaticaxes to the horizontal opposition in the model, which will then suppose that paradigms of signs are their “encyclopedic”dimension, in Umberto Eco’s sense, while their rules of combination constitute their“syntax”. Furthermore, enunciation is clearly involved in all sign manifestations as their deictic dimension; and their vertical interrelation of expression (signifier) and content (signified) would correspond to the interrelation of phonetics and semantics in verbal language. In this way, we arrive at asemiologicalquasi-systemic model as the following (see Figure 4):

Figure 4.

The horizontal axis covers the Jakobsonian values: theparadigmaticdimension corresponds to “discourse” in language, and thesyntagmaticdimension to syntax,evidently enough. The Saussurean vertical axis of the model articulatessignifier,deixis, andsignified.

Since the model is general, it does not yet distinguish sign types, even if there are such differences—icons more often integrate in significant paradigms (for comparison) than they form syntagmatic concatenations, whereas symbols inversely are most often syntagmatically concatenated, even when their paradigms are not clear or important. Nevertheless, all signs in principle are produced and perceived through these five instances. The differentiation of sign types happens on a deeper level, namely that of the underlying mental topology, because it pertains to thesort of meaningthat signs convey.

4. Topologies of the Mind

There are indeed different sorts of meaning. Example:

(1) A jailer enters the cell and tells the prisoner: “You are a free man. (You can go now)”

(2) A philosopher enters the cell and tells the prisoner: “(As a human being): You are free.”

(3) The prisoner’s wife enters the cell and says: “I love you. You are (so) free.”

In (1), the meaning I intend to exemplify is: “You can go now”. A declarative. In (2),the meaning could be: “Despite the fact that you are in prison, you are by constitution free to do what you do as a person, so it may be your own fault that you are here now.” A speculative hypothesis. In (3), the utterance points at a singular bond between two persons.

The semantics in (1) isperformative. It belongs to the realm ofsymbolicmeaning effects. By symbolic meaning is meant meaning directly affecting or establishing relations between speaker’s authority and speaker’s or hearer’s situation; its signs are strongly coded (or “arbitrary”, “conventional”) and have strong effects on situations linked to that of the symbolic communication. Symbolic meaning is often overtly modal and always person-related:I shall, you must, we will, he cannotetc., that is, it forms a modalinstruction.

In (2), the semantics is insteadinformative. I suggest classing it in a realm ofimaginarymeaning effects. Communication here invites to consider a state of affairs in the light of some hypothesis, knowledge or experience; correspondingly, signs are less strongly or ritually coded, and their semantics is modally epistemic or deontic (it is likely/suitable that...),inviting the addressee to take part in some act of imagination.Imaginary meaning is the main content of deliberative social life, where problems and possible developments are discussed and debated. On the individual level, we are appealing to imagination when we communicate in this mode.

And finally, in (3), the most difficult semiotic genre16, the semantics isformative:it emotionally connects the singularities of speaker and hearer in the realm of theirreality. This is what we expect the Jakobsonian “poetic function” to do in language,and the aesthetics to do in the artistic field. Signs in this realm typically appear in a totally amodal form and just refer to whatisthe case, importantly or not. No matter where: in the world, in the mind, on the canvas, on stage... Authority does not count here, logic does not count. Only singularity counts. In the realm of thereal meaning, we are in the tautological mode: things are what they are, I am what I am,etc. Proper names are signs reserved for this mode; no motivation works, not even conventionality.

保证统计数据质量,一方面是完善统计工作的趋势所在,另外一个方面在于为统计数据提供更多安全保障,从而不断提升实际工作质量。从使用要求上来看,对统计数据的质量问题进行关注,需要立足于数据自身准确性,同时兼顾统计数据完整性。所谓“准确性”,主要是指统计信息应该具备真实性和客观性,能够为数据使用者提供更加详细的依据[1]。“完整性”则是指需要保证统计信息在内容上的全面性与系统性,也就是不能存在数据残缺现象。除了这两项内容外,保证统计数据质量,还能在很大程度上为数据使用的及时性提供保障,也能够突出统计信息在时间方面上所具备的价值。

These three sorts or modes of meaning arenotconstituted by the nature of the signs we use, but by the nature of the mind we have.17

There are, I postulate, three major sign classes,symbols, icons, and diagrams,because the conscious mind is active in three correspondingly distinct endeavors.18We may be able to describe this variety by projecting it onto the line of “thinking” in the large sense spanning from attentive sensory and situational perception, at one end,to intense recollection, at the other end. The mind either lives in the present or in its memories; most often, however, it switches swiftly between these poles, and in the mental area that separates them, it attends to things it tries to know better: it “thinks”,in a narrower sense: it “reflects”.

A. Perception-oriented thinking underlies symbolic meaning, and the use of symbols, because perception is directly linked to action, speech acts, ritual gestures,exchanges of instructional signs, and other practical modalities (performative or deontic).

B. Memory-oriented thinking underlies iconic and existential, subjectively-real meaningin the sense indicated above, because the past loses its modality (must, shall,ought to, have to..., cannot) and becomes brutally factual, absolute, hence iconic and so much the more emotional.

C.In the interval separating A and B, that is, (A) the strongly modal and dynamic power play of symbolic meaning and (B) the amodal and rather static, fatal and biographic mental force of real-iconic meaning, we enjoy (C) a more or less extended region of conceptual, ideational, epistemic imagination and mental diagramming:imaginary meaningunfolds, as we attend to more “abstract” and “theoretic” endeavors involving planning, problem-solving and task learning.

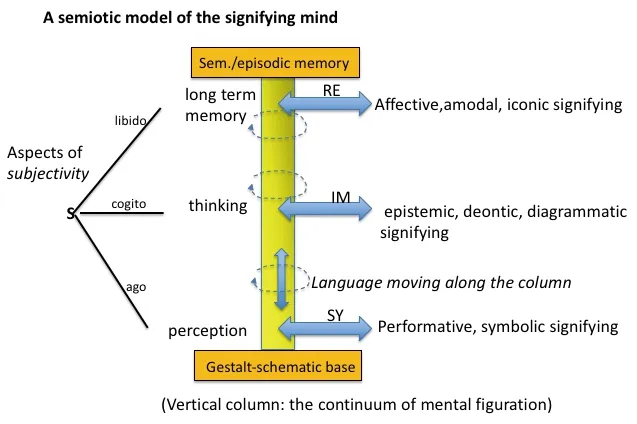

Our considerations lead us toward a new view of the way language and other sign“systems” communicate with the mind. The structural spirals of these “systems” slide around the column of mental figuration that spans from perception (A) to memory (B).Mental figuration(C, between A and B) is the topological activity that runs in thinking that remembers, doubts, criticizes, tries out variants of ideas, imagines possibilities,finds probabilities, elaborates ideals and norms, and finally wants and evaluates action, of self and others.

This analysis entails a representation of mental activity, meaning production,and subjectivity, which I propose to model by specifying its meaning mode and to conceive by gradual variation, as either (C) a standard epistemiccogitosubject, (B) an affectivelibidosubject, or (A) a performativeagosubject.

Parts of the memorizing mind are accessible to the conscious and volitive subject, whereas other parts of its iconic content are only accessible by involuntary or indirect occurrence (corresponding to the Freudian Unconscious). Modal strength increases (fromisthroughmay betomust be) by descent in the column, and attains a maximum in the performative mode of signifying, closely related to perception and action. At the base of perception, there is an automatic process ofGestaltformation that schematizes occurrences in the experienced pheno-physical space-time. Mental figuration is often characterized as “concrete” when close to perception, “abstract”when moving upwards to the possibilistic laboratory, and “irrational” when continuing upwards toward the finally “unspeakable” iconic realm of affective memory-based meaning. The model of the mind as a differentiated atelier or laboratory of meaning,as described here, will look like the following diagram (see Figure 5 below):

Figure 5.

This topological representation is not as such grounded in current neurocognitive research models, but it does take into account the cognitive idea that mental figuration must be situated between the instances of memory and perception, and that the model must be sensitive to the fact that acts of signifying can express all and any of the possible modes of this figuration.

According to this view, the mind fundamentally favors three principles of validity:power(immediate performative dynamics),truth(epistemic, imaginary, causal-natural or intentional-social), andaffect(amodal, existential, chance-related, singular) andthereforegives rise to the three major and fundamental sign types, symbols, diagrams,and icons, and to language, which covers all of these. Signs of all types are often cooccurrent with language, because thinking can “vertically” connect these different styles in many ways and indeed does so when meaning and expressions have to be multileveled, “mulitmodal”, as in theatre (text, gesture, music, painting, dance...). As we know from political life,power(A) andaffect(B) create dangerous alliances whentruth(C) is excluded from the complex; the search for truth, on the other hand, cannot exist in a vacuum—it has to be backed up from both sides, anchored in the existential real and defended by certain socio-symbolic, institutional reinforcements.

5. Towards a Semiotics of the Mind

Subjectivity is found not only in individuals but also in groups and even larger social institutional entities; the symbolic, imaginary, and real modes can be identified on the societal level of political power (symbolic), institutional discourse (imaginary), and established life forms (existentially real), all necessary for a society to exist.19Hence the massive intersubjectivity and inter-corporeality of human life-worlds. In this respect, individual minds and social structures are strongly isomorphic—an effect of human evolution—which explains our intuitive and more or less automatic concerns for the problems of the humanworldthat constitutes our condition of life: the shared world is our natural political concern and commitment, so to speak. It is easy, for example in literary fictions, to observe that the phenomenology of singular embodied minds merge with empathically experienced collective feelings and shared thoughts in historical situations that call for affective attention, planned action, constructive thinking, and criticism for lack of such. Meaning exists in a semiotic medium of“hermeneutic”, historical subjectivity and intersubjectivity in this sense.

Ferdinand de Saussure saw linguistics as a social science, and he also insisted that its basic units werepsychique, that is, mental and conceptual, as opposed to physical. This is a justified double claim if meaning is shaped on all levels, from mankind, civilizations, societies, to groups and individuals, as “fractal” iterations of the grounding triad we have identified in the semantics of the architecture briefly described here. The primordial importance of thewordin the interaction of language and thought, and the importance of thesignin the corresponding interaction between expressive behavior and the semiotics of the mind, further confirms Saussure’s claim that linguistics be the exemplary model of a general “semiology”, seen as the study of mind, meaning, and mankind: intentional interaction in the human and—we may add—the animal world.20The Swiss linguist’s leading ideas may be read today as his prolegomena to a general semiotics of meaning, mind, and mankind.

Notes

1 Author of the famousProlegomena to a Theory of Language(1943) that inspired generations of linguists and semioticians in the Saussurean tradition. Hjelmslev 1993.Saussure’s Prolegomena, I claim, is his CLG.

2 It is notoriously difficult to define theword, although language users normally do not experience that difficulty. It is apparently a natural kind, on a pair with other things that exist in time, such as melodies and numbers. Saussure offers the following definition of his basic unit (op. cit. p. 146): “une tranche de sonorité qui est, à l’exclusion de ce qui précède et de ce qui suit dans la chaîne parlée, le signifiant d’un certain concept.” He has to refer tola chaîne parlée, that is, tola parole, where the analyst must cut out a “slice”,une tranchethat he thinks means something. The entireCoursturns around the problem of this delimitation of the “slice”. Clauses are sometimes almost words, especially idioms,but sentences are definitely not. Nevertheless, Saussure’s examples are readily drawn from ordinary school grammars. Such grammars are not treatises of linguistics, but they are indispensable for the linguist’s argument. How is that? It all relies on the speakers’intuitions. It depends on a phenomenology of experienced meaning.

It is instructive to look at Saussure’s treatment of word classes,les parties du discours, in theCours. They are abstractions (p. 190), and their status is uncertain, he says, since the linguist cannot know if the intuitions of the language users are aware of these abstractions. It would be impossible for Saussure to decide, for example, that the distinction between open classes (nouns, verbs, adjectives) and closed classes (morphemes of all kinds), which, in cognitive linguistics, is based on the difference betweencategoriesandschemasthat interrelate categories, is alinguisticdistinction, unless the users say so. This is the serious philosophical limitation of Saussure’s project as he presented it himself; his nominalism made him believe that thought isonlyshaped by words or signs (p.155); without them, “la pensée est comme une nébuleuse”. (But then users’ intuitions are just such “nebulae”). It took most of a century before cognitive science could show thatthought really exists as such, and not only as contents of a “semiology”, so that a coherent semiology and a consistent linguistics could be built on it.

3 Lévi-Strauss was a co-founder, with Jakobsonet alii, of the journalWord,and was the author of its name.

4 I do not consider construction grammar (Goldberg, 1995) and what has followed it to be successful approaches to integration of words and sentences, although they are influential.Theirsyntax-lexicon continuumclaim ignores the semiotic distinction between word and sentence. See Tomasello 2003.

5 Biplanarity is the property of perceptions and ideas that connect contents on two planes of which one “means” the other. Some such biplanary items are signs, but not all. Mirror images “mean” what they show, which is outside the mirror, and they are not signs,because the link between image and imaged is causal, whereas signs are intentional.

6 Interestingly, sentences carry reference, whereas words do not. So, sentences, hence their propositional meaning, are closer to things than words are.

7 See in particular Merker in Brandt and Do Carmo, 2015. On the importance of words before sentences, see Bickerton, 2009.

8 See Brandt, 2007 [On Consciousness and Semiosis].

9 Daniel Dennett has famously ridiculed Descartes’ discovery of the autonomy of thought by rejecting the “Cartesian theater”. Dennett’s analytic philosophy renounces on analyzing introspection.

10 See Brandt and Cronquist, 2018.

11 See “On Tonal Dynamics and Musical Meaning” inMusic and Meaning, Brandt and Do Carmo, 2015.

12 See Brandt and Cronquist in Brandt, 2019.

13 My reviewer writes that I have not proved that the word is related to these instances,phonetics, syntax, sentence semantics, discourse semantics, and enunciation. My explanation here is indeed apodictic: I only want the reader to see what I mean, given that the components are default in modern linguistics. Should I “prove” that a word has phonetic properties? That it is part of the syntax and the semantics of a sentence? That word meanings (concepts) are involved in discourse meanings? That words indicate speakers’ interrelations? If I wanted todenythis, I would rather have to argue fiercely.The problem I am addressing is how to conceive of the way these standard components are connected, and based on words and thinking. This is not a trivial problem, and I do not pretend to have solved it, only to address it, as clearly as I can.

14 Another way of describing the idea is to let the lexical formationssurroundthe infralinguistic instance of thought; words form the periphery of our thought.

15 Again, I do not “prove” this, but below, I intend to show where it leads us. Theories, by the way, cannot be proven; they are not theorems. They just connect good problems.

16 With this distinction ofsymbolic, imaginary, and real meaning, I am offering a special interpretation of Jacques Lacan’s triad of “orders”, without implying that his psychoanalytic theory as a whole must follow. Lacan’s concept of a “real” order was in particular inspired by his philosophical friend Georges Bataille. In the perspective I am developing here, one could say that I am comparing two prominent semiologies, one by Peirce and the other by Lacan; for very important reasons concerning themeaning types,never before considered in semiotics, I have to give Lacan’s proposal a slight lead. What is important, however, is neither the terminologies nor the affiliations, but instead the analysis in itelf.

17 Human evolution seems to have extended the interval between symbolic-performative and real-affective meaning, giving rise to the intermediate realm of less practically oriented reflection. The sign types we call symbols and icons are recognized in all semiotic traditions, although they are understood in many different ways; the Peircean understanding of them is not particularly clarifying and partly misleading (iconic firstness and symbolic thirdness are extremely bad ideas; his -nesses belong to a project of no semiotic interest).

18 The Peirceanindicesare biplanary objects of reflective thought, in which a perceived part“signifies” a non-perceived part, by causation in a wide sense: smoke -> fire, symptom ->illness, etc. They are not intended as signs, but we refer to them as signs metaphorically,since, like signs, they operate on two planes. In fact, the connection from the perceived part to the non-perceived part has to be understood through some sort of diagram (strictly causal, mereological, or other).

19 See Brandt, 2017 on the ecological grounding of meaning. I have suggested to think of the relation of society and mind as a “fractal” structure: the same basic series of meaning modes repeats itself from the largest to the smallest scale. Thus, meaning floats freely within each mode from one scale to another. See also Brandt, 2020 on the sociosphere as a semiosphere, and the semiotic isomorphies between mind and society.

20 Some animals can learn words, but few can shape sentences. The mind model presented here might shed some light on, or further stimulate, existing research on animal semiotics.

Language and Semiotic Studies2022年1期

Language and Semiotic Studies2022年1期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Un système de signaux maritimes: Saussure’s Example of a Visual Code