社会效价对预测群体成员行为的影响:群体规范和个人偏好在其中的作用*

尹 军 孙淼燕 孙鸿莉 艾丹枫 林 静 郭秀艳

(1.宁波大学心理学系暨研究所,宁波 315211;2.华东师范大学心理与认知科学学院,上海 200062;3.复旦大学老龄研究院,上海 200433)

1 Introduction

Humans profoundly depend on social interactions to collectively act and affiliate with others(Hirschfeld,2001).Successful social interaction requires humans not only to passively react to the behaviors of others but also to predict and anticipate these behaviors.Evidently,people are able to generate appropriate predictions of an individual’s behaviors by acquiring knowledge of this particular individual(Blakemore &Decety,2001).This is knowledge of their beliefs,mental states,preferences,and traits underlying the observed behaviors,which can be situationally inferred from perceived scenes or generated based on previous experiences(Baker et al.,2009;Koster-Hale &Saxe,2013;Kruse &Degner,2021).However,it is overwhelming to accumulate individual-specific knowledge for each individual to predict behaviors,and sometimes,we lack this type of knowledge(Bodenhausen et al.,2012).Moreover,making predictions based on individualized information is a cognitively demanding process in a complex and fast-paced social world(Apperly&Butterfill 2009;Schneider et al.,2012).Hence,relying on only individual-specific knowledge is challenging and poses an information processing bottleneck.A critical way to tackle this challenge is by using the knowledge of the social group to which the predicted individuals belong,which captures the shared behavioral tendencies of its members(Bodenhausen et al.,2012;Liberman et al.,2017).As such,even without knowledge of a particular individual,the individual is predicted to share behaviors and attributes with the associated group members.Nevertheless,not all behaviors are treated as of similar classes,but they may have beneficial or detrimental consequences for others and have different evaluative valences;that is,they are positive or negative(Gilbert&Basran,2019;Lebowitz et al.,2019).The current study explored whether and how behavior valence influences behavior prediction based on group membership.

Thinking about others in terms of their group memberships is known as social categorization,by which we place individuals into social groups and treat them as being in similar categories(Bodenhausen et al.,2012;Liberman et al.,2017).We usually form beliefs associated with social groups,which are stereotypes,and apply them to an unknown group member without having to consider whether the particular individual has the assumed characteristics.Even the immediately learned attributes of an individual,including attitudes and traits,are readily generalized to other group members(Chen &Ratliff,2015;Crawford et al.,2002;Ranganath &Nosek,2008).Importantly,it has been reported that when a group is perceived as a real“social group”in which a crowd of individuals is perceived as a unified entity,individuals generalize behavioral traits to other group members more than when a group is seen as an aggregate of individuals(Crawford et al.,2002).However,studies describing this trend emphasize that the stable attributes or traits underlying behaviors are extended within or between group members instead of predicting behaviors per se.In a transient setting,behaviors are interpreted as being directly driven by situational demands(e.g.,beliefs about group norms)and situation-specific short-term states(e.g.,goals and preferences),but traits that can constrain mental states are typically conceptualized by their relative stability and characterize one’s repetitive behaviors across situations(Kruse&Degner,2021).For example,individuals with negative traits do not always exhibit negative behaviors,given that group norms prescribe positive behaviors and that negative,norm-incongruent behavior is often the exception in a social group.Recently,direct evidence has documented that social groups also guide our predictions and expectations about group members’behaviors,and unknown group members are predicted to be likely to show the same behaviors as known group members,similar to predicting social conformity(Duan et al.,2021;Yin et al.,2022).However,behaviors can have different valences,and valence is probably the most basic psychological dimension on which people can easily position observed stimuli(Alves et al.,2017);thus,understanding whether and how predicting group-consistent behaviors is influenced by the valences of behaviors is important.That is,when group members exhibit positive(e.g.,helping)or negative behaviors(e.g.,hindering),is an individual associated with this group predicted to exhibit these two valenced behaviors to a similar degree?

Alves and colleagues(2017)found that positively valenced behavior is generally more common than negatively valenced behavior.It is assumed that people’s mental representations of their social worlds mirror this prevalence of positive behaviors,and thereby,positive attributes,including behaviors,are judged as being easily shared across social individuals,as our mind is adapted to the structural properties of the external ecology(Unkelbach et al.,2020).This approach implies that predicting others’behaviors based on group membership is influenced by behavior valence,and group members would be predicted to show fewer group-consistent negative behaviors than positive behaviors based on the positivity prevalence.Moreover,as suggested,the positivity prevalence regarding behaviors is largely due to moral norms(Alves et al.,2017;Peters et al.,2017;Unkelbach et al.,2019),in which positive behaviors are largely accepted and promoted by all societies and negative behaviors are widely prohibited(Ahmed et al.,2020;Gilbert &Basran,2019).Given that social groups are embedded in society,moral norms usually constrain group norms(Kanngiesser et al.,2022;Phillips &Cushman,2017).In this case,group norms may be perceived to inherit some of the content of moral norms.Hence,we further hypothesize that when group members show negative behaviors,the perceived norm related to this group is less likely to support these behaviors.Thus,a new individual associated with this group is less likely to be predicted to engage in group-consistent behaviors than when the individual observes group members showing positive behaviors.Namely,the decrease in predicting group-consistent negative behaviors relative to group-consistent positive behaviors should be mediated by perceived group norms about approving of predicted behaviors.Nevertheless,more than situational-specific group norms,individuals’personal mental states can also drive behaviors through which group members prefer to implement positive behaviors.Given that social categorization is a basic process through which to learn group knowledge marks group members as fundamentally similar(Bodenhausen et al.,2012;Liberman et al.,2017),such group member state information might be extended to other members.Then,the inferred individual state of preferring positive behaviors would guide the prediction of behaviors.In this case,rather than the perceived group norm,the perceived individual preference may explain the decrease in predicting group-consistent negative behaviors relative to group-consistent positive behaviors.Hence,these two processes of perceived group norms and perceived individual preference were examined.

In the current study,positive(negative)behavior was operationalized as helping(hindering)another,as previously established,to explore social evaluations about individuals based on their social interactions(Hamlin et al.,2007;Isik et al.,2017).Two experiments were conducted.First,we assessed whether a new group member is predicted to be less likely to follow group-consistent(i.e.,the majority’s)negative behaviors than group-consistent positive behaviors and whether the perceived group norm or perceived individual preference mediates this relation(Experiment 1).Then,Experiment 2 once again tested the replicability of the results of Experiment 1 but introduced a moderating factor of group entitativity that expresses the extent of“groupness”(Crawford et al.,2002)and describes the degree to which a group is perceived as a real entity to examine whether the difference between predicting negative and positive behaviors is truly based on group membership.

2 Experiment 1

Can behavior valences shape perceived group norms or individual differences and thereby affect predictions of group-consistent behaviors? Experiment 1 examined this question by presenting three persons in a social group,with two showing commonly positive or negative behaviors,and asking the participants to predict how the third person would behave and report perceived group norms that approve of these behaviors and perceived individual preferences for the third individual.

2.1 Methods

2.1.1 Participants

Two hundred and six participants recruited from a university campus participated in this experiment and received a gift after completing the investigation.The sample size was determined as follows.We conducted a pilot study that was similar to the current one,except that the items measuring individual preferences were not included.The pilot study enrolled 138 participants,and the measured effect size(i.e.,Cohen’s d)was 0.78 for the difference in predicting behaviors between conditions and 0.41 for the difference in perceived group norms between conditions.Hence,the expected effect size was set to 0.41 to detect differences between conditions for two measurements.Using G*Power 3.1(Faul et al.,2009),the sample size was determined by using a power analysis where the alpha level was set at 0.05,the power was set at 0.80 to detect a difference between two independent groups,and the minimum suggested sample size to reach the effect size of 0.41 was 190 individuals(i.e.,95 for each condition).To be conservative and have enough valid participants,each condition tested at least 100 participants.Finally,103 participants(44 men and 59 women,mean age=22.00 years,SE=0.31)were tested in the positive behavior condition,and 103 participants(43 men and 60 women,mean age=22.51 years,SE=0.22)were tested in the negative behavior condition.The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the Department of Psychology at the authors’University and was performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

2.1.2 Procedure and measures

All participants were told that we were conducting research on their views about valenced behaviors and were asked to read stories presented in the questionnaires and evaluate the corresponding items.To create group-related behaviors,the story described three persons in a social group with two behaving similarly,and the participants were asked to predict how the third person would behave.This scenario has been used with recorded videos to predict goal-directed behaviors and has been documented as useful for examining group-related behaviors effectively(Yin et al.,2022).Each participant was presented with a story,which was assigned either two group members helping another individual who did not belong to any group(i.e.,positive behavior)or two group members hindering another individual who did not belong to any group(i.e.,negative behavior).

In the positive behavior condition,the participants were told,“One day,Zhang,Zhao and Tao wore the same red hat and went on a sightseeing excursion to walk up a hill to watch the sunrise.While walking,they saw three other people(i.e.,Jia,Sun,and Li)carrying heavy items up the hill.Zhang helped Jia carry the items up the hill,and Zhao helped Sun carry the items up the hill.”

In the negative behavior condition,the participants were told,“One day,Yang,Zhou and Zheng wore the same yellow hat and went on a sightseeing excursion to walk up a hill to watch the sunrise.While walking,they saw three other people(i.e.,Qian,Chen,and Wu)carrying heavy items up the hill.Yang made it more difficult for Qian to carry the items up the hill,and Zhou made it more difficult for Chen to carry the items up the hill.”

Next,the participants were asked,“To what extent will Tao act toward Li as Zhang did toward Jia(or as Zhao did toward Sun)?”in the positive behavior condition and“To what extent will Zheng act toward Wu as Yang did toward Qian(or as Zhou did toward Chen)?”in the negative behavior condition to match the measurement of the dependent variable but with different actor names.The participants then completed the battery of process measures.Two items assessed the perceived group norm(e.g.,“If Tao acted toward Li as Zhang did toward Jia[or as Zhao did toward Sun],to what extent do members of the group of Zhang,Zhao and Tao approve of doing this on a regular basis?”and“If Tao acted toward Li as Zhang did toward Jia[or as Zhao did toward Sun],to what extent does the average member of the group of Zhang,Zhao and Tao support doing this on a regular basis?”).Two other items assessed the perceived individual preference(e.g.,“If Tao acted toward Li as Zhang did toward Jia[or as Zhao did toward Sun],to what extent would Tao be willing to do this?”and“If Tao acted toward Li as Zhang did toward Jia[or as Zhao did toward Sun],to what extent would Tao prefer to do this?”).The items measuring the perceived group norm followed previous research(Peters et al.,2017)measuring the perceptions of the injunctive normativity of behaviors and were edited to fit the current scenarios.All items used the same 7-point scale(1=completely unlikely to 7=completely likely).Concerning perceived individual preferences,we referred to studies measuring individual mental states and preferences when predicting behaviors in children(Chalik et al.,2014;Shilo et al.,2021).

2.1.3 Analysis

We averaged the two item ratings to attain a perceived group norm composite rating(Spearman r=0.566,p<0.001)and used the same procedure for the perceived individual preference items to create a composite score(Spearman r=0.709,p<0.001).Importantly,the correlations between the item ratings measuring perceived group norms and those measuring perceived individual preference were very weak(0.068≤Spearman r≤0.182,p≥0.052),suggesting that perceived group norms and perceived individual preferences are two different mental constructs.Then,for each dependent measurement,an independent t test was conducted(please note that the uncorrected degrees of freedom were reported).To examine the roles of group norms and individual preferences in predicting group-consistent behaviors,we conducted a simultaneous mediation analysis to investigate which process(es)statistically mediated the effect of behavior valence on the extent of predicted group-consistent behaviors.In this mediation analysis,the condition of positive(helping)behavior was coded as -1,the condition of negative(hindering)behavior was coded as 1,and the standardized effects were reported.We report all measures,manipulations,and exclusions for all experiments.All data,materials and analysis codes are publicly available at the OSF and can be accessed at https://osf.io/w64k3/? view_only=bce3c2e9d43e4b2aaec 4204dcc79c83a.

2.2 Results and discussion

2.2.1 Predicted behavior

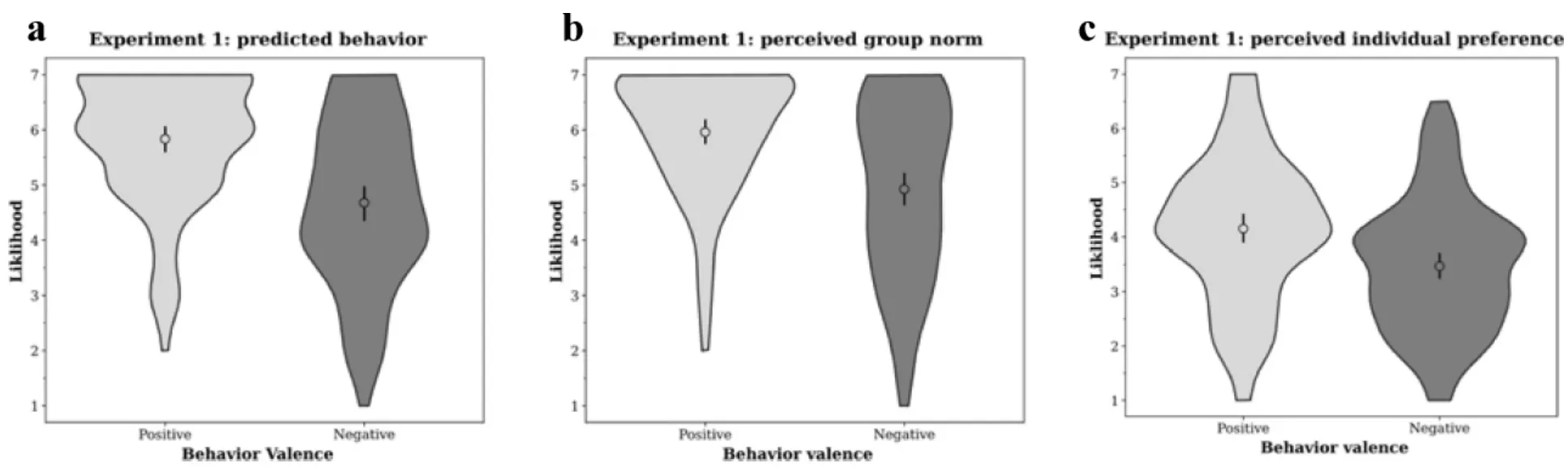

The participants predicted the group member to be less likely to follow group-consistent negative behaviors(i.e.,in the condition of negative behavior;M=4.68,SE=0.15)than group-consistent positive behaviors(i.e.,in the condition of positive behavior;M=5.83,SE=0.12;95% CI of difference=[-1.53,-0.79],t(204)=6.15,p<0.001,d=0.86,BF10=2.44×106;Figure 1a).

Figure 1.Results of Experiment 1.Violin plots represent(a)predicted group-consistent behavior,(b)the perceived group norm and(c)the perceived individual preference as a function of behavior valence.Large circles indicate means,and black vertical lines indicate the bootstrapping confidence intervals(CIs)of the means.

2.2.2 Perceived group norm

The perceived group norm,which was believed to drive a group member to follow the majority’s behaviors,was different between the two valenced behaviors(t(204)=5.41,p<0.001,d=0.75,BF10=7.02 ×104).Specifically,the group norm of approving of negative behaviors(M=4.93,SE=0.16)was perceived as weaker than that of approving of positive behaviors(M=5.96,SE=0.11;95% CI of difference=[-1.41,-0.66];Figure 1b).

2.2.3 Perceived individual preference

The perceived individual preference,which was supposed to drive a group member to follow the majority’s behaviors,was different between the two valenced behaviors(t(204)=3.80,p<0.001,d=0.53,BF10=1.13×102).Specifically,the individual preference for implementing group-consistent behaviors was rated lower when the behaviors were negative(M=3.48,SE=0.12)than when they were positive(M=4.15,SE=0.13;95% CI of difference=[-1.02,-0.32];Figure 1c).

2.2.4 Mediation

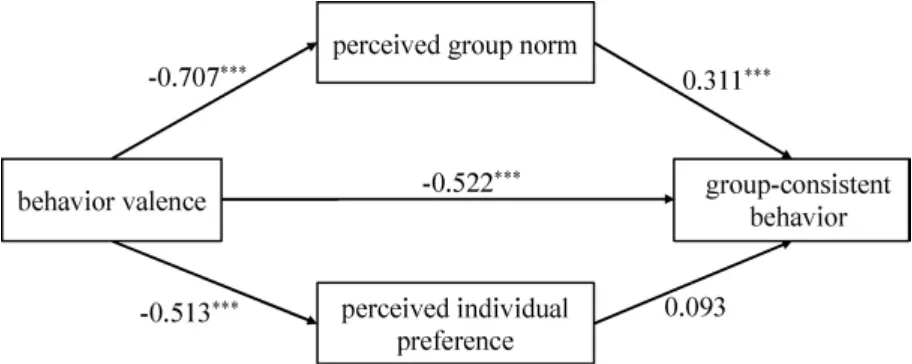

Figure 2.Multiple mediation analysis from Experiment 1.All values reflect the effects while controlling for all other paths.Asterisks indicate significant paths:***p<0.001.

The behavior valence affected two process measures,and hence,we conducted a simultaneous mediation analysis(Figure 2).The results show that the perceived group norm mediated the effect of behavior valence in predicting group-consistent behaviors(indirect effect=-0.110,95% CI from 5000 sample bootstraps=[-0.185,-0.054]),but the perceived individual preference did not statistically mediate the effect(indirect effect=-0.024,95% CI from 5000 sample bootstraps=[-0.072,0.010]).

3 Experiment 2

Although the experiment found that negative valence weakens the perceived group norm that approves of this behavior and thereby shapes the predictions of group-consistent behaviors,it is risky to conclude that this process is based on group membership per se.As only a unified social group in which group members have common physical features and goals was presented in Experiment 1,the results of Experiment 1 may be applied to any crowd of individuals.If our focused behavior prediction is indeed based on group membership,the difference between predicting group-consistent positive and negative behaviors and the different perceived group norms among the two valenced behaviors should be modulated by group entitativity.In this experiment,the three persons in the stories were allocated to two different groups:a high entitativity group,similar to Experiment 1,and a low entitativity group in which group members were loosely connected.When the groupness became loose,the group norm approving the negative behavior should be devalued because the prevailing moral norm still works,but the constraint from social group is weakened;thereby,the likelihood of predicting group-consistent negative behaviors is decreased.Hence,predictions of group-consistent behaviors should be more influenced by the behavior valence in the loose group than in the entitative group.

3.1 Methods

3.1.1 Participants

In line with Experiment 1,the difference between the two valenced behaviors should be detected and replicated.Hence,we referred to the sample size of each condition used in Experiment 1 and planned to test at least 100 participants for each condition in the current experiment.Finally,four hundred and nine students who had not participated in Experiment 1 participated in this experiment.Specifically,the condition of positive behavior in the high entitativity group tested 104 participants(53 men and 51 women,mean age=21.97 years,SE=0.21),the condition of positive behavior in the low entitativity group tested 101 participants(28 men and 73 women,mean age=21.33 years,SE=0.35),the condition of negative behavior in the high entitativity group tested 102 participants(51 men and 51 women,mean age=21.56 years,SE=0.17),and the condition of negative behavior in the low entitativity group tested 102 participants(31 men and 71 women,mean age=21.91 years,SE=0.24).

3.1.2 Procedure and measures

The tested scenarios were almost the same as those used in Experiment 1,except that each behavior valence was matched to two different descriptions of group entitativity at the beginning of the tested stories,resulting in a 2(group entitativity:high vs.low)×2(behavior valence:positive vs.negative)between-subject design.Each participant was assigned to a condition.Those in the high group entitativity condition were told the following information:“Zhang,Zhao and Tao often stayed together and had a good relationship.One day,Zhang,Zhao and Tao wore the same red hat and went on a sightseeing excursion to walk up a hill to watch the sunrise.”Those in the low group entitativity condition were told the following:“Zhang,Zhao and Tao had not spent time together and did not know each other.One day,Zhang,Zhao and Tao wore different hats and formed a temporary group to walk up a hill to watch the sunrise.”The descriptions of the group members’behaviors were identical to those used in Experiment 1.

Next,the participants were asked to report their predictions,perceived group norms and perceived individual preferences,as in Experiment 1.To verify the manipulation of group entitativity,the participants were also asked to evaluate whether the three persons in the story could be treated as belonging to a group(i.e.,group entitativity)using two items.These two items(“To what extent are Zhang,Zhao and Tao closely connected?”and “To what extent are Zhang,Zhao and Tao a unit?”)were established according to the definition and characteristics of a real social group(Morewedge et al.,2013)and referred to the work of He et al.(2021).The two items were measured on a 7-point scale(1=not at all to 7=very much).

3.1.3 Analysis

We averaged the mean item ratings to attain a perceived group norm composite rating(Spearman r=0.658,p<0.001)and used the same procedure for the perceived individual preference items to create a composite score(Spearman r=0.673,p<0.001)and for the perceived group entitativity items to create a composite score(Spearman r=0.739,p<0.001).Importantly,the correlations between the item ratings measuring perceived group norms and the item ratings measuring perceived individual preference were very low(0.063 ≤Spearman r ≤0.086,p ≥0.503),again suggesting that perceived group norms and perceived individual preferences are two different mental constructs.As in Experiment 1,we conducted a simultaneous mediation analysis to investigate which process(es)statistically mediated the effect of behavior valence on the extent of predicting group-consistent behaviors for each group entitativity condition.

3.2 Results and discussion

3.2.1 Perceived group entitativity

A 2×2 analysis of variance(ANOVA)with group entitativity(high vs.low)and behavior valence(positive vs.negative)as between-subject variables confirmed the validity of our manipulation.The analysis shows that the main effect of group entitativity was significant(F(1,405)=112.20,p<0.001,ηp2=0.22),showing that group was perceived as having higher entitativity in the high entitativity condition(M=5.22,SE=0.09)than in the low entitativity condition(M=3.80,SE=0.09);unexpectedly,the main effect of behavior valence was also significant(F(1,405)=18.49,p<0.001,ηp2=0.04),showing that group was perceived as having higher entitativity in the positive behavior condition(M=4.80 SE=0.09)than in the negative behavior condition(M=4.23,SE=0.09);however,the interaction effect between factors was not significant(F(1,405)=1.47,p=0.227,ηp2<0.01).Hence,the interaction effect found below cannot be attributed to the different entitativity ratings between positive and negative behaviors.To further rule out the explanation of the unmatched perceived group entitativity between different valenced behaviors,the perceived group entitativity was treated as a covariate in the mediation analysis,and we found results similar to those obtained without this covariate.

Importantly,in both the positive behavior and negative behavior conditions,the participants perceived the group as having higher entitativity in the high group entitativity condition(positive behavior:M=5.43,SE=0.11;negative behavior:M=5.01,SE=0.13)than in the low group entitativity condition(positive behavior:M=4.17,SE=0.15,95%CI of difference=[0.88,1.63],t(203)=6.65,p<0.001,d=0.93,BF10=3.23 ×107;negative behavior:M=3.44,SE=0.14,95% CI of difference=[1.2,1.95],t(202)=8.29,p<0.001,d=1.16,BF10=3.52×1011).Hence,our manipulation is valid.

3.2.2 Predicted behavior

A 2×2 ANOVA with group entitativity(high vs.low)and behavior valence(positive vs.negative)as between-subject variables was conducted.The analysis shows that the main effect of group entitativity was significant(F(1,405)=9.30,p=0.002,ηp2=0.02),demonstrating that the group member was rated as being more likely to adopt group-consistent behaviors when group entitativity was high(M=5.15,SE=0.11)than when group entitativity was low(M=4.69,SE=0.11).The main effect of behavior valence was also significant(F(1,405)=122.96,p<0.001,ηp2=0.23),supporting the results of Experiment 1 and showing that the group member was predicted to be less likely to exhibit group-consistent negative behaviors(M=4.08,SE=0.11)than group-consistent positive behaviors(M=5.77,SE=0.11).Importantly,the interaction effect between factors was significant(F(1,405)=4.45,p=0.035,ηp2=0.01).The analysis of simple effects shows that the influential effect of behavior valence in predicting group-consistent behaviors(i.e.,differences in the rated likelihood of predicting group-consistent negative and positive behaviors)was smaller when the group had high entitativity(d=0.91,95%CI of d=[0.62,1.19])than when the group had low entitativity(d=1.28,95% CI of d=[0.98,1.58];Figure 3a).Importantly,the predicted group member was rated as more likely to adopt group-consistent negative behavior in the high group entitativity condition(M=4.47,SE=0.17)than in the low group entitativity condition(M=3.69,SE=0.18;95% CI of difference=[0.30,1.27],t(202)=3.21,p=0.002,d=0.45,BF10=17.80).However,no such effect was found when the group members positively helped others(95% CI of difference=[-0.21,0.50],t(203)=0.79,p=0.430,d=0.11,BF10=0.20).

Figure 3.Results of Experiment 2.Violin plots represent(a)predicted group-consistent behavior,(b)the perceived group norm and(c)the perceived individual preference as a function of group entitativity and behavior valence.Large circles indicate means,and black vertical lines indicate the bootstrapping CIs of the means.

3.2.3 Perceived group norm

A 2×2 ANOVA with group entitativity and behavior valence as between-subject variables was conducted on perceived group norms.The main effect of group entitativity was significant(F(1,405)=4.67,p=0.031,ηp2=0.01),showing that the group member was rated to more fully adopt group norms that support the predicted behaviors when group entitativity was high(M=5.49,SE=0.10)than when group entitativity was low(M=5.18,SE=0.10).The main effect of behavior valence was also significant(F(1,405)=72.09,p<0.001,ηp2=0.15),showing that the group norm of approving negative behaviors(M=4.73,SE=0.10)was also perceived as weaker than that of approving positive behaviors(M=5.94,SE=0.10).Importantly,the interaction effect between factors was significant(F(1,405)=4.07,p=0.044,ηp2=0.01).The analysis of simple effects shows that the influential effect of behavior valence on perceived group norms(i.e.,differences in the rated likelihood of approving of negative and positive behaviors)was smaller when the group had high entitativity(d=0.67,95% CI of d=[0.39,0.95])than when the group had low entitativity(d=1.00,95% CI of d=[0.70,1.29];Figure 3b).Importantly,when the group members hindered others,their social group was rated as having a stronger group norm approving of this behavior in the high group entitativity condition(M=5.02,SE=0.17)than in the low group entitativity condition(M=4.43,SE=0.18;95% CI of difference=[0.12,1.08],t(202)=2.45,p=0.015,d=0.34,BF10=2.47).However,no such effect was found when the group members helped others(95% CI of difference=[-0.27,0.32],t(203)=0.14,p=0.887,d=0.02,BF10=0.15).

3.2.4 Perceived individual preference

A 2×2 ANOVA with group entitativity and behavior valence as between-subject variables showed the main effect of group entitativity to be insignificant(F(1,405)=1.44,p=0.232,ηp2<0.01).The main effect of behavior valence was significant(F(1,405)=40.19,p<0.001,ηp2=0.09),showing that the individual preference of hindering others(M=3.40,SE=0.09)was judged to be weaker than that of helping others(M=4.21,SE=0.09).The interaction effect between factors did not reach significance(F(1,405)=0.01,p=0.917,ηp2<0.01;Figure 3c).

3.2.5 Mediation

As in Experiment 1,we conducted a simultaneous mediation analysis but for each group entitativity condition.When the group entitativity was high(Figure 4a),the perceived group norm mediated the effect of behavior valence in predicting group-consistent behaviors(indirect effect=-0.135,95% CI from 5,000 sample bootstraps=[-0.211,-0.078]),but perceived individual preference did not statistically mediate the effect(indirect effect=-0.018,95%CI from 5,000 sample bootstraps=[-0.064,0.014]),supporting the results of Experiment 1.However,when the group entitativity was low(Figure 4b),the perceived group norm still mediated the effect of behavior valence in predicting group-consistent behaviors(indirect effect=-0.177,95%CI from 5,000 sample bootstraps=[-0.267,-0.104]).However,the perceived individual preference statistically mediated the effect(indirect effect=-0.073,95% CI from 5,000 sample bootstraps=[-0.137,-0.033]),and its effect was weaker than that of the perceived group norm.

Since the perceived group entitativity was varied with the valenced behaviors in each group entitativity condition,the perceived group entitativity was used as a covariate in each condition,and the same mediation analysis procedure as above was conducted.The results were similar to those found above.Hence,the effect of behavior valence in predicting group-consistent behaviors was not due to the perceived group entitativity differences across the differently valenced behaviors.Further analysis showed that the group entitativity moderated the effect of behavior valence on perceived group norms and thereby reduced the likelihood of predicting groupconsistent negative behaviors.

Figure 4.Multiple mediation analyses from Experiment 2 for the conditions of high group entitativity(a)and low group entitativity(b).All values reflect effects found while controlling for all other paths present.Asterisks indicate significant paths:***p<.001.

4 General discussion

The present research found that predictions of group-consistent behaviors are influenced by behavior valences.Specifically,when group members performed negative behaviors(i.e.,hindering),an individual associated with this group was predicted to be less likely to exhibit similar behavior than when group members performed positive behaviors(i.e.,helping).In addition,the perceived group norms by which all group members approved of positive or negative behaviors but not the perceived individual preferences statistically mediated this influential relation(Experiment 1).Importantly,when the social group became loose,the group norm approving the negative behavior was perceived as being weakened and thereby decreased the likelihood of predicting group-consistent negative behaviors;moreover,the effect of behavior valence in predicting group-consistent behaviors was more pronounced when individuals formed a loose group than when they formed an entitative group,and this effect was still mediated by the perceived group norm(Experiment 2).Hence,predicting behaviors based on group membership is largely driven by perceived group norms and is accordingly valence dependent.

The observed difference between predictions of positive and negative behaviors adds to the existing evidence of asymmetric genetic attribution and the updating of representations of such behaviors,overall suggesting that actions are processed differently in the brain based on their valence and that positivity is prevalent(Alves et al.,2017;Lebowitz et al.,2019;Moutsiana et al.,2013;Sharot &Garrett,2016;Siegel et al.,2018;Unkelbach et al.,2020).This finding seems to contradict the observation that the negative behaviors of group members are easily mapped onto another member;for instance,stereotypes are usually related to negative behaviors.Nevertheless,this observation may reflect our explicit judgments of disliked persons or objects.Indeed,compared to positive attributes,negative attributes are rated as more likely to be shared between disliked persons(Alves et al.,2017),and negative attitudes toward a stimulus category generalize more to similar stimuli than positive attitudes(Fazio et al.,2015).In our research,the newly formed groups were not associated with the participants,and the findings may be largely due to the cognitive processing of positive and negative behaviors without strong motivations to avoid negative stimuli.

Valence-dependent behavior predictions are mainly mediated by perceived group norms when the predicted individual belongs to an entitative group.Importantly,under conditions of low group entitativity,people shift to the individual level and appeal to individual preferences to predict behaviors.Nevertheless,a loose group does not mean that a social group is never present,which is why both perceived group norms and individual preferences contributed to valence-dependent behavior prediction in the high entitativity group.This finding implies that when predicting others’behaviors,people flexibly consider their social situations and mainly utilize group information to predict behaviors(Vijayakumar et al.,2021).This seems to contradict the correspondence bias of the tendency for people to overemphasize personal or personality-based explanations of behaviors observed in others while underemphasizing situational explanations(Lee &Barnes,2021).Correspondence bias is usually observed when explaining completed behaviors,and our study focuses on predicting behaviors.It may be that during explanation or attribution,we must obtain stable characteristics of a person to explain and anticipate cross-situation behavioral repetition,but behavior prediction depends more on the transient situation and personal state needed to predict what will be done in a given situation.Hence,these two processes have different functional adaptations and thereby influence understanding behavior in different ways.

Why does behavior valence influence perceived social norms and thereby impact the predictions of group-consistent behaviors? It is possible that people,at least from the observer’s perspective,represent different norms in a hierarchical manner.Specifically,group norms are represented at the subordinate level,which is embedded in the higher-level representation of moral norms.In this case,even when all group members implement a negative behavior and approve of it,given that it is constrained by the moral norm that prohibits this negative behavior,the perceived group norm for the negative behavior is never higher than that for the positive behavior.Given that moral/group norms can be treated as situational constraints to build a hypothesis space for behavior prediction(Phillips &Cushman,2017),positive behaviors that are approved of by more group members should be predicted to be more likely to be implemented by a new group member,than negative behaviors.Importantly,when the boundary of social groups become ambiguous,that is the groupness is weakened,the representation of group norms may be directly determined by the higher-level representation of moral norms,as inferring group norms from group members’expectations and behaviors is largely based on the social group boundary.Accordingly,perceived social norm,especially those that conflict with moral norms,decrease.Therefore,we observed that the group norm approving the negative behavior was weakened in Experiment 2.The assumption of hierarchical representations of social norms does not support social norms having different types(Brennan et al.,2013),but does establish on initial framework for how these kinds of social norm representations are linked.

Nevertheless,positive and negative behaviors are operationalized as helping and hindering actions,but there are many manifestations of such actions,such as donating and bullying.Additionally,the current study used only three agents for each group,and group size usually plays an important role in group processing.Moreover,numerous behaviors are visually observed instead of textually described.Future studies should adopt other instantiations of positive and negative actions,explore more examples,and use recorded human behaviors to test the generalizability of our findings.To conclude,predicting behaviors based on group membership is valence dependent,and this influential relation occurs because the group norm associated with positive behaviors is approved of by group members more than that associated with negative behaviors.Hence,the extent to which people value group norms varied with valenced group-consistent behaviors and flexibly utilize group-related situations to predict behaviors.