牙周局部炎症影响小鼠肠道机械及免疫屏障功能

谢美莲 余挺 卓颖 黄馨 谢宝仪 轩东英,3 章锦才,3

1.南方医科大学附属口腔医院牙周科,广州 510280;2.广州医科大学附属口腔医院牙周科,广州 510150;3.中国科学院大学存济医学院附属杭州口腔医院牙周科,杭州 310006

·牙周病学专栏·

牙周局部炎症影响小鼠肠道机械及免疫屏障功能

谢美莲1余挺2卓颖1黄馨1谢宝仪1轩东英1,3章锦才1,3

1.南方医科大学附属口腔医院牙周科,广州 510280;2.广州医科大学附属口腔医院牙周科,广州 510150;3.中国科学院大学存济医学院附属杭州口腔医院牙周科,杭州 310006

目的探索牙周局部炎症对小鼠肠道屏障(生态屏障、机械屏障、免疫屏障)功能的影响。方法将20只雄性C57BL/6J小鼠随机分为牙周炎组(P组)和对照组(C组),每组10只。P组使用浸泡牙龈卟啉单胞菌的丝线行牙周结扎10 d,C组假性结扎。分离上颌骨测量牙槽骨丧失量,取肠道内容物行16s rRNA焦磷酸测序分析菌群结构,免疫组织化学检测回肠组织occludin、claudin2、NOD2蛋白的表达。结果P组的牙槽骨丧失量高于C组(P<0.001)。P组与C组的主要菌门及卟啉单胞菌种比例无统计学差异(P>0.05),P组occludin、claudin2、NOD2的表达高于C组(P=0.039,P=0.011,P=0.039)。结论牙周局部炎症在一定程度上影响了小鼠肠道的机械及免疫屏障功能。

牙周炎;炎症性肠病;肠道菌群;机械屏障

牙周炎是由菌斑微生物引发的以牙周支持组织破坏为主要特征的慢性炎症性疾病[1],是成年人失牙的主要原因[2]。流行病学资料显示牙周炎与一系列全身系统性疾病包括胃肠道疾病如炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease,IBD)等相关[3-5]。约旦流行病学调查显示IBD人群的牙周炎患病率是非IBD人群的4.9~7.0倍[6]。IBD人群的牙周袋探诊深度较非IBD人群高0.8~0.9 mm[7]。然而,牙周炎与胃肠道疾病的关联机制并不清楚,菌群失调可能是其重要机制[8]。研究[9]发现口腔喂饲牙龈卟啉单胞菌(Porphy-romonas gingivalis,P. gingivalis)可导致小鼠肠道菌群结构改变和肠道机械屏障受损,但未诱导出明确的牙周炎和牙周组织破坏[10]。至此仍无明确证据表明,牙周炎对肠道功能包括菌群结构和肠道屏障有不利影响。本研究以结扎法诱导实验性牙周炎,通过检测牙周炎状态下小鼠肠道的生态、机械及免疫屏障变化,探索牙周炎对小鼠肠道功能的影响,为牙周炎与肠道疾病的关联机制提供依据。

1 材料和方法

1.1牙周炎模型的建立与验证

1.1.1实验性牙周炎模型建立将20只SPF级雄性C57BL/6J小鼠(22周龄,体重27.2 g± 2.5 g)随机分为牙周炎组(P组)和对照组(C组),每组10只。4%水合氯醛腹腔注射麻醉下,P组使用浸泡P. gingivalis ATCC33277肉汤24 h的5-0丝线行双侧上颌第二磨牙(M2)牙周结扎,C组使用浸泡无菌水的5-0丝线行假性结扎。一次性结扎10 d后,处死小鼠取材。

1.1.2实验性牙周炎模型验证分离上颌骨,用10%中性甲醛溶液固定。取一侧脱钙液(10%EDTA,0.2 mol·L-1Tris)脱钙3周,M2颊侧正面朝下包埋,切5 μm厚切片,苏木精-伊红(hematoxylin-eosin,HE)染色。体视显微镜下拍照,定性分析牙周组织炎症。另一侧于沸水中煮15 min,剥净软组织、漂白,1%亚甲基蓝水溶液染色1 min,冲洗、晾干,体视显微镜下拍照,Image J软件(NIH公司,美国)测量3个磨牙颊腭侧共18个位点的釉牙骨质界-牙槽嵴顶距离[11],均值为样本的牙槽骨丧失量。

1.216s rRNA焦磷酸测序法检测肠道菌群结构

分离肠道的回肠至结肠部分[12],5 mL生理盐水冲取肠道内容物,混匀,PowerSoil®DNA提取试剂盒(MO BIO公司,美国)提取总DNA,操作按照试剂盒说明书进行。所得DNA进行凝胶电泳,确认DNA质量合格。针对16s rRNA的V3、V4高变区序列设计特异性引物(V3,TACGGRAGGCAGCAG;V4,GGACTACCAGGGTATCTAAT),进行聚合酶链反应(polymerase chain reaction,PCR)扩增。扩增程序设定为:95 ℃ 2 min,95 ℃ 20 s、55 ℃15 s、72 ℃ 5 min 循环25次,72 ℃ 10 min。对扩增后的产物进行提纯,末端修复,连上接头、测序引物后,采用Illumina Miseq高通量平台测序,测序策略为PE 300。测序所得序列通过去除低质量序列、接头污染序列及含N比例大于5%序列等过程完成数据过滤,得到可信的目标序列。目标序列采用PEAR序列拼接算法将双末端测序序列根据末尾的重叠情况进行拼接,导入分析软件QIIME 1.8.0进行分析[13]。

1.3免疫组织化学检测回肠组织occludin、claudin2、NOD2蛋白的表达

取长度为2 cm的回肠(距回盲端2 cm),4%多聚甲醛固定,常规脱水、浸蜡、包埋,切4 μm厚切片。切片常规脱蜡、水化,微波热抗原修复13 min(修复液1 mmol·L-1Tris-EDTA),冷却后PBS缓冲液(0.01 mol·L-1,pH 7.2~7.4)冲洗,30 mL·L-1过氧化氢灭活15 min,10%山羊血清封闭10 min。37 ℃下孵育一抗(Abcam兔抗小鼠occludin、兔抗小鼠claudin2、大鼠抗小鼠NOD2一抗分别孵育2、2、3 h),PBS冲洗,37 ℃下孵育二抗30 min,PBS冲洗, DAB(工作浓度1∶20)显色30 s,苏木素复染,常规脱水、透明,中性树胶封片,Olympus IX83显微镜下镜检,Image Pro Express 6.0软件拍照。每组随机选取5个样本,每个样本随机选取5个不连续切片上的5个视野(×400),利用ImagePro Plus 6.0软件计算蛋白染色的平均光密度值。

1.4统计学处理

采用SPSS 17.0软件进行数据分析,以均数±标准差描述结果。牙槽骨丧失量、菌群比例以及平均光密度值均采用两独立样本t检验行两组间比较。

2 结果

2.1实验性牙周炎模型成功建立

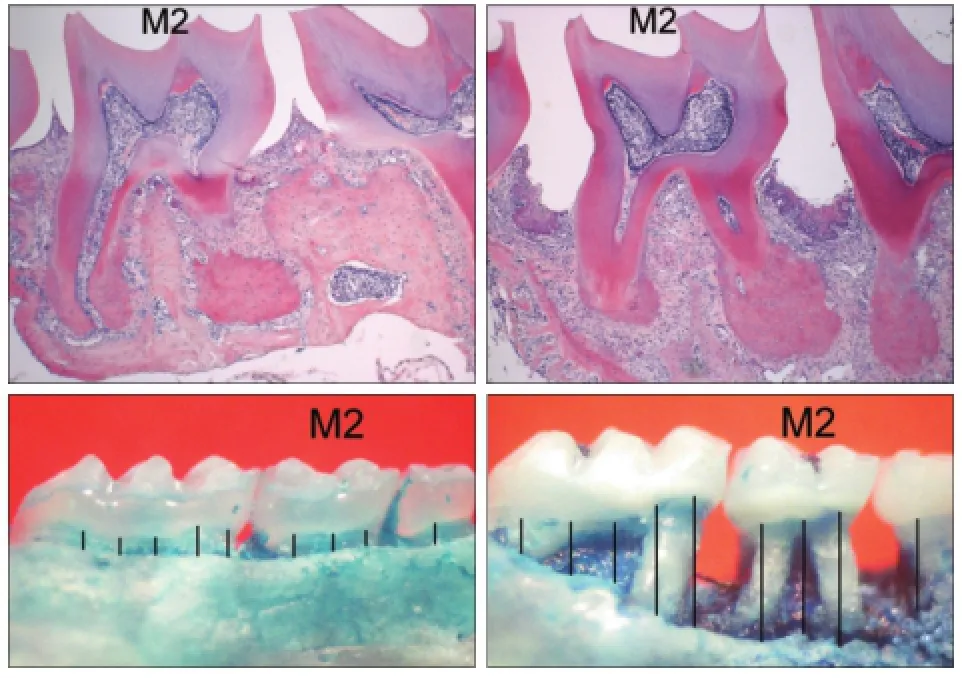

颌骨HE染色(图1上)显示,P组牙龈退缩,上皮及上皮下结缔组织大量炎症细胞浸润,C组牙周组织正常。亚甲基蓝染色(图1下)显示,P组出现明显的牙槽骨丧失。

图1 实验性牙周炎模型的验证Fig 1 Verification of experiment periodontitis model

P、C组的牙槽骨丧失量分别为(0.38±0.06)、(0.15±0.02)mm,统计分析表明,P组的牙槽骨丧失量高于C组(P<0.001)。

2.2肠道菌群结构分析比较

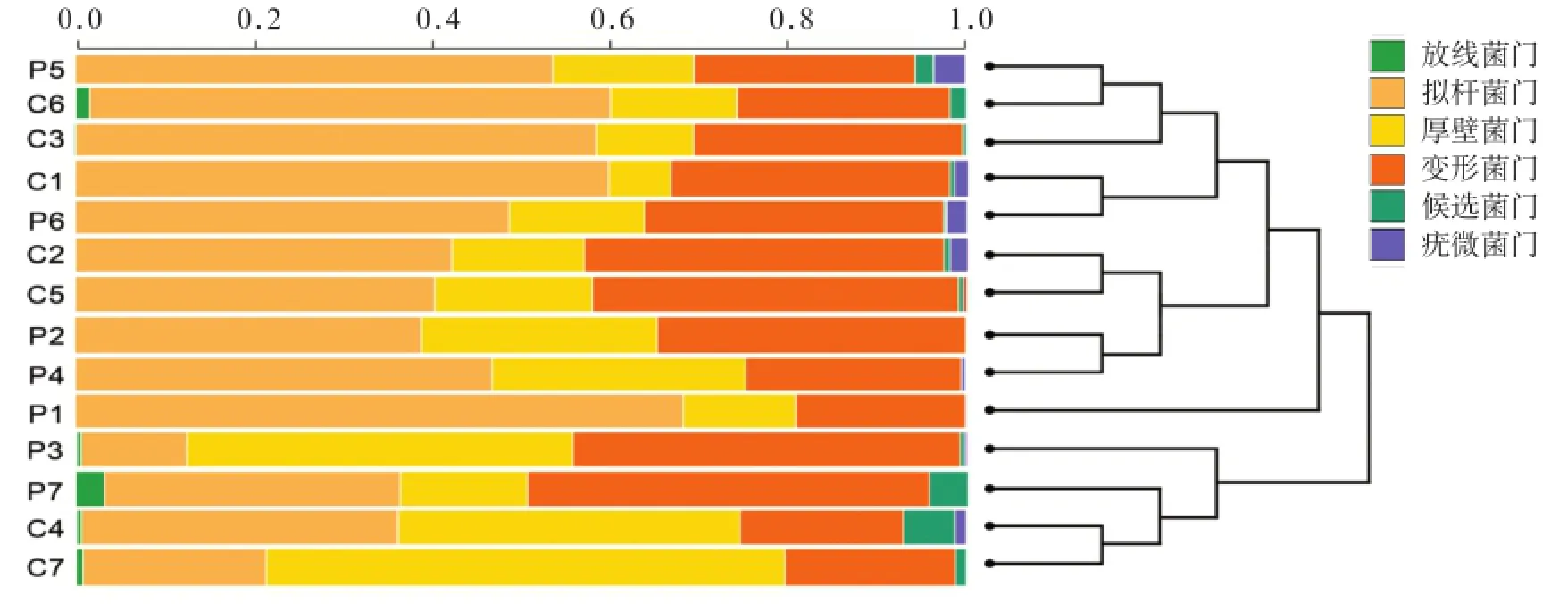

本次测序肠道检测出8个主要菌门:拟杆菌门、厚壁菌门、变形菌门、放线菌门、候选菌门、疣微菌门、无壁菌门、脱铁杆菌门,其中前5种菌门占测得序列的99.6%以上。聚类树图显示组内样本一致性较好(图2)。

图2 各样本肠道菌群结构聚类树图Fig 2 Cluster dendrogram generated of the gut microbiota across the samples

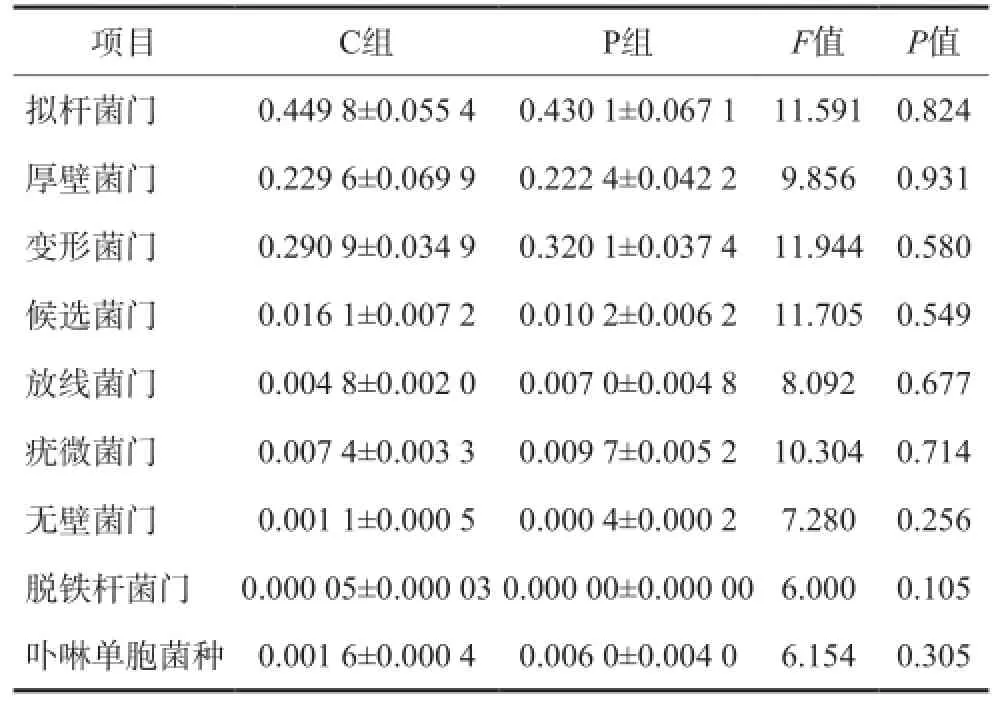

2组主要菌门及卟啉单胞菌种比例的比较见表1。与C组相比,P组拟杆菌门、厚壁菌门、候选菌门、无壁菌门、脱铁杆菌门比例下降,变形菌门、放线菌门、疣微菌门、卟啉单胞菌种比例升高,但均无统计学差异(P>0.05)。对于脱铁杆菌门, C组检出比例为0.05‰,P组未检出,二者间无统计学差异(P>0.05)。

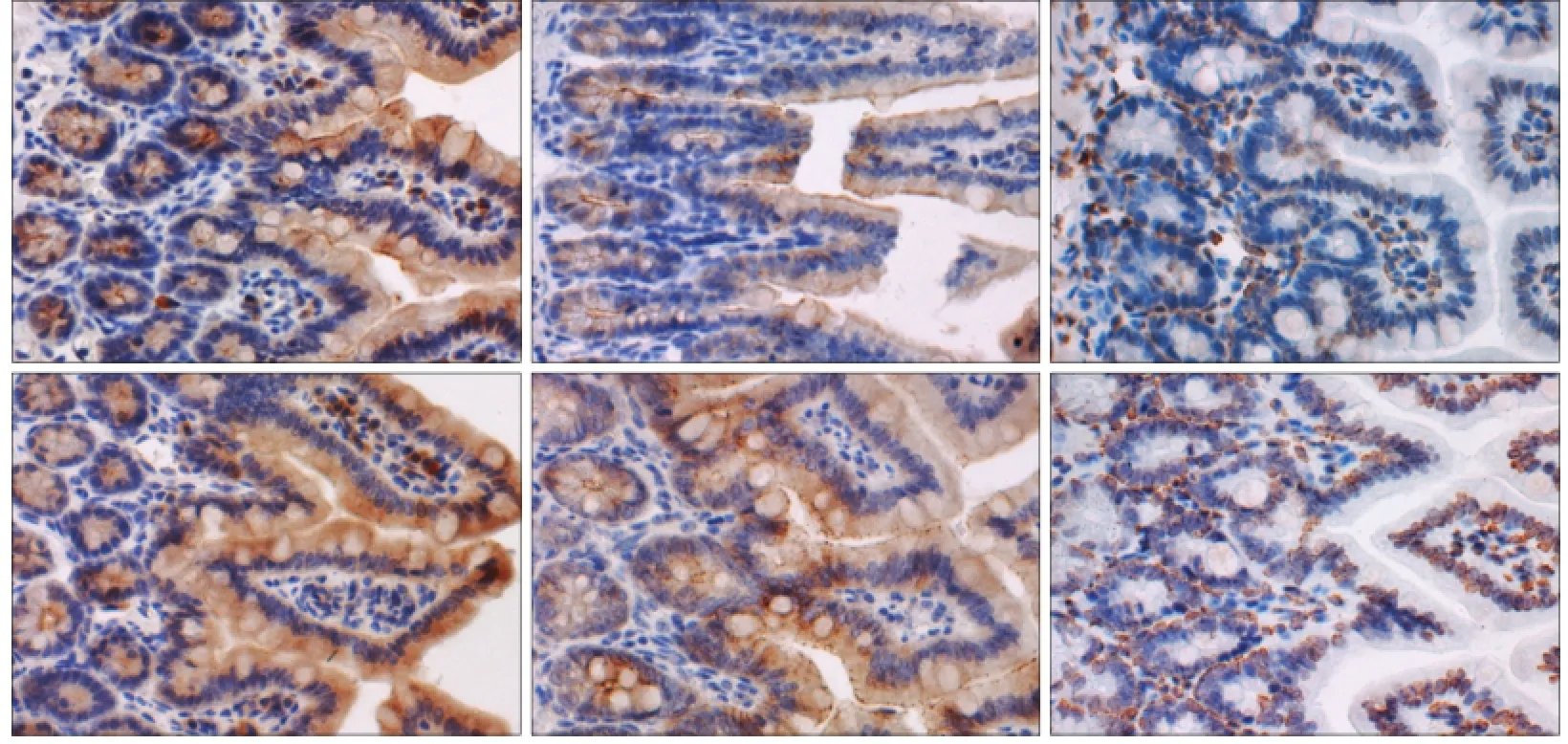

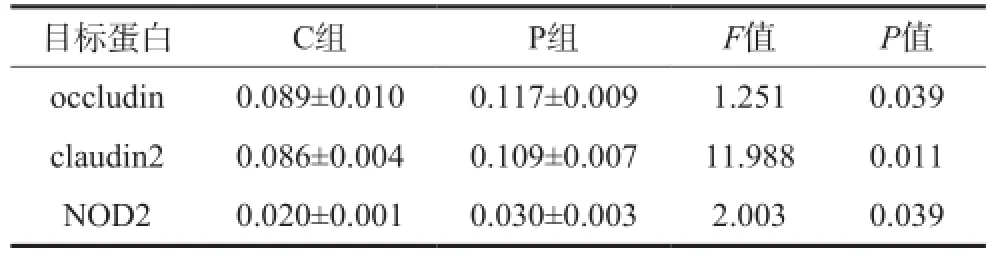

2.3回肠组织中occludin、claudin2、NOD2蛋白的表达

免疫组织化学结果(图3)显示,occludin、claudin2均表达于回肠黏膜上皮细胞的胞浆,NOD2表达于上皮细胞及间质单核巨噬细胞系的胞核。P组occludin、claudin2、NOD2的表达高于C组(P=0.039,P=0.011,P=0.039)(表2)。

表1 2组主要菌门及卟啉单胞菌种比例的比较Tab 1 Comparison of the abundance of the main phyla and genus parabacteroides of two groups

图3 2组回肠组织occludin、claudin2及NOD2蛋白的表达 免疫组织化学 × 400Fig 3 Occludin, claudin2 and NOD2 in the ileum of two groups immunohistochemistry × 400

表2 2组回肠组织occludin、claudin2、NOD2蛋白表达的比较Tab 2 Comparison of occludin, claudin2 and NOD2 expression in ileum of two groups

3 讨论

肠道屏障包括由肠道正常菌群组成的生态屏障、由完整上皮和各类紧密连接蛋白(如occludin、claudin2[14])组成的机械屏障以及由肠道黏膜内各类免疫细胞及免疫蛋白(如NOD2[15])组成的免疫屏障,三者在功能上紧密联系,共同行使肠道免疫功能[16]。本研究结果显示,牙周炎组小鼠肠道菌群结构无显著改变,但其机械屏障和免疫屏障发生了一定程度的变化。

在生态屏障方面,牙周局部炎症对小鼠肠道菌群的菌门结构及卟啉单胞菌种比例并无显著影响。值得注意的是,尽管没有显著性,牙周炎小鼠的肠道未能检测出脱铁杆菌门的存在。Robertson等[17]认为脱铁杆菌门与人类健康或疾病状态都没有明确关联。有趣的是,近年有研究[18]发现,脱铁杆菌门在牙周炎患者的龈下菌群中的比例高于非牙周炎患者。脱铁杆菌门也存在于感染牙髓中并被认为可能是根尖周疾病的潜在病原菌[19]。此外,在肥胖小鼠、结肠炎小鼠以及被猪鞭虫感染的小型猪的肠道中,均观察到了脱铁杆菌门比例的升高[20-22]。脱铁杆菌门似乎倾向于在炎症部位活跃,但却在牙周炎小鼠的肠道中“缺席”,可能是菌群调控的结果。

在机械屏障方面,occludin是紧密连接蛋白中最早被发现的结构蛋白[23]。occludin与claudins家族共同组成转运通道,控制上皮屏障通透性,其过量表达时上皮通透性明显增加[14]。Choi等[24]研究发现,牙周炎患者的牙龈上皮出现occludin的过量表达;而claudin2的上调及其他claudins的改变被认为与IBD的疾病活动期相关[25]。在本实验中,牙周炎小鼠同时出现occludin和claudin2的表达上调,表明其肠道机械屏障功能受损。此外,claudin2的上调还伴随着肠道上皮细胞对抗原大分子胞吞作用的增强[26]。NOD2在牙周炎小鼠的高表达验证了这一点。

NOD2是胃肠道上皮细胞及髓系、淋巴系造血细胞内的先天性免疫蛋白[27],其可识别进入胞内的革兰阴性菌和革兰阳性菌的胞壁肽聚糖,启动对病原体的应答反应[15]。牙周炎小鼠肠道出现NOD2的高表达,说明肠道免疫屏障被激活,这可能是机械屏障受损的结果,也可能说明肠道正常菌群已经发生了一定程度的变化。

本研究采用单次牙周结扎建立小鼠牙周炎模型,主要基于以下两点:1)多次麻醉将引起注射局部炎症反应[28];牙周结扎时采用腹腔注射麻醉,多次结扎可能引起腹腔、肠道及系统的非特异性炎症反应,混淆本实验结果。2)Nakajima团队的实验中,在单次109CFU数量的活牙龈卟啉单胞菌管饲后的48 h可检测到P组的卟啉单胞菌种比例显著高于C组[9],提示大量喂饲牙龈卟啉单胞菌可造成肠道菌群结构改变;但即使是多次喂饲,实验小鼠上也并没有观察到显著的牙槽骨吸收[10];因此,牙龈卟啉单胞菌喂饲不足以引起典型的牙周炎。单次结扎可最大限度地减少建模手段本身对系统性炎症水平及肠道菌群结构变化的影响。本实验因结扎使用的丝线含有牙龈卟啉单胞菌,尽管菌群检测的结果显示P组的卟啉单胞菌种比例并不显著高于C组,但尚不能否认本实验的结果与牙龈卟啉单胞菌的吞菌无关。

综上所述,本实验结果尚不能说明牙周局部炎症对小鼠肠道菌群结构有显著的调控,但在一定程度上影响了其肠道屏障功能,包括机械屏障受损以及免疫屏障激活,提示控制牙周疾病可能有利于预防和控制胃肠道疾病,但其相关的具体生理机制仍需深入研究和探讨。

[1] Hajishengallis G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation[J]. Nat Rev Immunol,2015, 15(1):30-44.

[2] 骆凯, 闫福华. 牙周病与全身健康[J]. 中国实用口腔科杂志, 2009, 2(4):203-206. Luo K, Yan FH. Periodontal diseases and human health[J]. Chin J Pract Stomatol, 2009, 2(4):203-206.

[3]朱习华, 刘丽, 许文青. 牙周病与糖尿病关联性的Meta分析[J]. 广东牙病防治, 2014, 22(2):76-78. Zhu XH, Liu L, Xu WQ. Meta-analysis of the relationship between periodontitis and diabetes[J]. J Dent Prevent Treat,2014, 22(2):76-78.

[4] Gurav AN. The implication of periodontitis in vascular endothelial dysfunction[J]. Eur J Clin Invest, 2014, 44(10):1000-1009.

[5] Vavricka SR, Manser CN, Hediger S, et al. Periodontitis and gingivitis in inflammatory bowel disease: a case-controlstudy[J]. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2013, 19(13):2768-2777.

[6] Habashneh RA, Khader YS, Alhumouz MK, et al. The association between inflammatory bowel disease and periodontitis among Jordanians: a case-control study[J]. J Periodont Res, 2012, 47(3):293-298.

[7] Brito F, de Barros FC, Zaltman C, et al. Prevalence of periodontitis and DMFT index in patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis[J]. J Clin Periodontol, 2008, 35(6): 555-560.

[8] Chassaing B, Gewirtz AT. Gut microbiota, low-grade inflammation, and metabolic syndrome[J]. Toxicol Pathol,2014, 42(1):49-53.

[9] Nakajima M, Arimatsu K, Kato T, et al. Oral administration of P. gingivalis induces dysbiosis of gut microbiota and impaired barrier function leading to dissemination of enterobacteria to the liver[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(7):e0134234.

[10] Arimatsu K, Yamada H, Miyazawa H, et al. Oral pathobiont induces systemic inflammation and metabolic changes associated with alteration of gut microbiota[J]. Sci Rep, 2014,4:4828.

[11] Kimura S, Nagai A, Onitsuka T, et al. Induction of experimental periodontitis in mice with Porphyromonas gingivalisadhered ligatures[J]. J Periodontol, 2000, 71(7):1167-1173.

[12] Belzer C, Gerber GK, Roeselers G, et al. Dynamics of the microbiota in response to host infection[J]. PLoS One, 2014,9(7):e95534.

[13] Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools[J]. Nucleic Acids Res, 2013, 41(Database issue):D590-D596.

[14] Anderson JM, Van Itallie CM. Tight junctions and the molecular basis for regulation of paracellular permeability[J]. Am J Physiol, 1995, 269(4 Pt 1):G467-G475.

[15] Barnich N, Aguirre JE, Reinecker HC, et al. Membrane recruitment of NOD2 in intestinal epithelial cells is essential for nuclear factor-κB activation in muramyl dipeptide recognition[J]. J Cell Biol, 2005, 170(1):21-26.

[16] Zhang K, Hornef MW, Dupont A. The intestinal epithelium as guardian of gut barrier integrity[J]. Cell Microbiol, 2015,17(11):1561-1569.

[17] Robertson BR, O'Rourke JL, Neilan BA, et al. Mucispirillum schaedleri gen. nov., sp. nov., a spiral-shaped bacterium colonizing the mucus layer of the gastrointestinal tract of laboratory rodents[J]. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol, 2005, 55 (Pt 3):1199-1204.

[18] Kumar PS, Griffen AL, Barton JA, et al. New bacterial species associated with chronic periodontitis[J]. J Dent Res,2003, 82(5):338-344.

[19] Siqueira JF, Rocas IN, Cunha CD, et al. Novel bacterial phylotypes in endodontic infections[J]. J Dent Res, 2005 (6):565-569.

[20] Walker A, Pfitzner B, Neschen S, et al. Distinct signatures of host-microbial meta-metabolome and gut microbiome in two C57BL/6 strains under high-fat diet[J]. ISME J, 2014,8(12):2380-2396.

[21] Li RW, Wu S, Li W, et al. Alterations in the porcine colon microbiota induced by the gastrointestinal nematode Trichuris suis[J]. Infect Immun, 2012, 80(6):2150-2157.

[22] Berry D, Schwab C, Milinovich G, et al. Phylotype-level 16S rRNA analysis reveals new bacterial indicators of health state in acute murine colitis[J]. ISME J, 2012, 6(11):2091-2106.

[23] Furuse M, Hirase T, Itoh M, et al. Occludin: a novel integral membrane protein localizing at tight junctions[J]. J Cell Biol,1993, 123(6 Pt 2):1777-1788.

[24] Choi YS, Kim YC, Ji S, et al. Increased bacterial invasion and differential expression of tight-junction proteins, growth factors, and growth factor receptors in periodontal lesions[J]. J Periodontol, 2014, 85(8):e313-e322.

[25] Zeissig S, Burgel N, Gunzel D, et al. Changes in expression and distribution of claudin 2, 5 and 8 lead to discontinuous tight junctions and barrier dysfunction in active Crohn's disease[J]. Gut, 2007, 56(1):61-72.

[26] Luettig J, Rosenthal R, Barmeyer C, et al. Claudin-2 as a mediator of leaky gut barrier during intestinal inflammation [J]. Tissue Barriers, 2015, 3(1/2):e977176.

[27] Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Viala J, et al. Nod2 is a general sensor of peptidoglycan through muramyl dipeptide (MDP)detection[J]. J Biol Chem, 2003, 278(11):8869-8872.

[28] Lisowska B, Szymańska M, Nowacka E, et al. Anesthesiology and the cytokine network[J]. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online), 2013, 67:761-769.

(本文编辑李彩)

Periodontal inflammation affects the mechanical and immune barrier functions of mice gut

Xie Meilian1, Yu Ting2,Zhuo Ying1, Huang Xin1, Xie Baoyi1, Xuan Dongying1,3, Zhang Jincai1,3.(1. Dept. of Periodontology, The Affiliated Hospital of Stomatology, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510280, China; 2. Dept. of Periodontology, The Affiliated Hospital of Stomatology, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou 510150, China; 3. Dept. of Periodontology, Hangzhou Dental Hospital, Savaid Medical School, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Hangzhou 310006, China)

Supported by: The National Natural Science Foundation of China (81271160, 81371151, 81470750). Correspondence: Zhang Jincai, E-mail: jincaizhang@live.cn.

ObjectiveTo explore the effects of periodontal inflammation on the functions of gut barrier (ecological barrier,mechanical barrier, and immune barrier) in mice. MethodsTwenty male C57BL/6J mice were randomly divided into periodontitis (P) or control (C) groups. The P group was subjected under a 10-day ligation with Porphyromonas gingivalis to induce periodontitis, whereas the C group was ligated with sham. Maxillae were obtained to assess alveolar bone loss. The phylogenetic structure and diversity of microbial communities in the gut were analyzed by 16s rRNA pyrosequencing. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed to determine the expressions of occludin, claudin2, and NOD2 in the ileum. ResultsCompared with the C group, the P group displayed significant alveolar bone loss (P<0.001). In addition, no significant influence on the main phyla and genus Parabacteroides of the two groups was observed (P>0.05). However, the ileum of the P group showed significantly upregulated occludin, claudin2, and NOD2 (P=0.039, P=0.011, and P=0.039, respectively). Conclusion Periodontal inflammation influences to some extent the mechanical and immune barrier functions of the mice gut.

periodontitis;inflammatory bowel diseases;gut microbiota;mechanical barrier

R 781.4

A

10.7518/hxkq.2016.04.019

2015-12-16;

2016-03-18

国家自然科学基金(81271160,81371151,81470750)

谢美莲,硕士,E-mail:nymphaea468@126.com

章锦才,教授,博士,E-mail:jincaizhang@live.cn