Metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma in isolated retroperitoneal lymph node without evidence of primary tumor in kidneys: A caes report

Lisa BE Shields, Arash Rezazadeh Kalebasty

Abstract BACKGROUND Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) plays a diagnostic, therapeutic,and prognostic role in myriad urologic malignancies, including testicular carcinoma, renal cell carcinoma (RCC), and upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma. RCC represents 2% of all cancers with approximately 25% of patients presenting with advanced disease. Clear cell RCC (CCRCC) is the most common RCC, accounting for 75%-80% of all RCC.CASE SUMMARY A 71-year-old man presented with a history of benign prostatic hypertrophy. He was asymptomatic without any hematuria, pain, or other urinary symptoms. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed a 1.8 cm left retroperitoneal lymph node. There was no evidence of renal pathology. A core biopsy was performed of the left para-aortic lymph node. Although the primary tumor site was unknown, the morphological and immunohistochemical features were most consistent with CCRCC. A RPLND was performed which revealed a single mass 5.5 cm in greatest dimension with extensive necrosis. The retroperitoneal lymph node was most compatible with CCRCC. A nephrectomy was not conducted as a renal mass had not been detected on any prior imaging studies. The patient did not receive any type of adjuvant therapy. The patient underwent surveillance with serial CT scans with contrast of the chest, abdomen,and pelvis for the next 5 years, all of which demonstrated no recurrent or metastatic disease and no evidence of retroperitoneal adenopathy.CONCLUSION Our unique case emphasizes the therapeutic role of metastasectomy in metastatic CCRCC even in the absence of primary tumor in the kidneys.

Key words: Oncology; Renal cell carcinoma; Clear cell carcinoma; Lymph node dissection; Retroperitoneal; Metastasis; Nephrectomy without primary site; Case report

INTRODUCTION

Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) has an important diagnostic,therapeutic, and prognostic function in several urologic malignancies[1]. Indicated most commonly for testicular carcinoma, it has also been used in renal cell carcinoma(RCC) and upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma[1-3]. In the United States, there are approximately 74000 new cases and approximately 15000 deaths from RCC annually[4]. Greater than 90% of patients with metastatic RCC have clear cell RCC(CCRCC) with more than 25% of patients presenting with advanced disease[5,6].

LND remains controversial in the treatment of RCC[1,7,8]. Radical nephrectomies historically involved LND, however, this latter procedure is now utilized primarily for improving the accuracy of staging and for stratifying patients for clinical trials[9].The current guidelines for RCC recommend LND only when clinically suspicious nodes are present[10,11]. Although lymph node metastasis is only 4%-6% in RCC[12],extension of RCC to a regional isolated retroperitoneal lymph node is often associated with a poor prognosis after nephrectomy including a higher incidence of metastatic disease and low response rates to immunotherapy[5,7,8,13,14]. It has been reported that the 5-year metastasis-free survival of patients with RCC nodal metastases is 16%[7].Several studies do not support a progression-free or overall survival benefit of LND in either metastatic or non-metastatic RCC following nephrectomy[1,8,12]. However,patients with isolated retroperitoneal nodal metastasis and aggressive RCC may experience long-term survival after LND[1,7,8,13]. Pathological assessment of nodal stage offers valuable prognostic insight as positive nodal status is independently associated with worse survival in both metastatic and non-metastatic RCC[1,7,15].

We report a remarkable case of retroperitoneal lymph node metastasis most consistent with CCRCC without a primary site. The differential diagnosis of the retroperitoneal lymph node based on the immunohistochemical staining analysis is discussed.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 71-year-old man presented with a lengthy history of benign prostatic hypertrophy.

History of present illness

He was asymptomatic without any hematuria, pain, or other urinary symptoms. The ECOG performance status was 1.

History of past illness

He had a lengthy history of benign prostatic hypertrophy.

Physical examination

Height: 6 feet (1.83 m); Weight: 225 lbs (102 kg); Body mass index: 30.5 kg/m2.

Imaging examinations

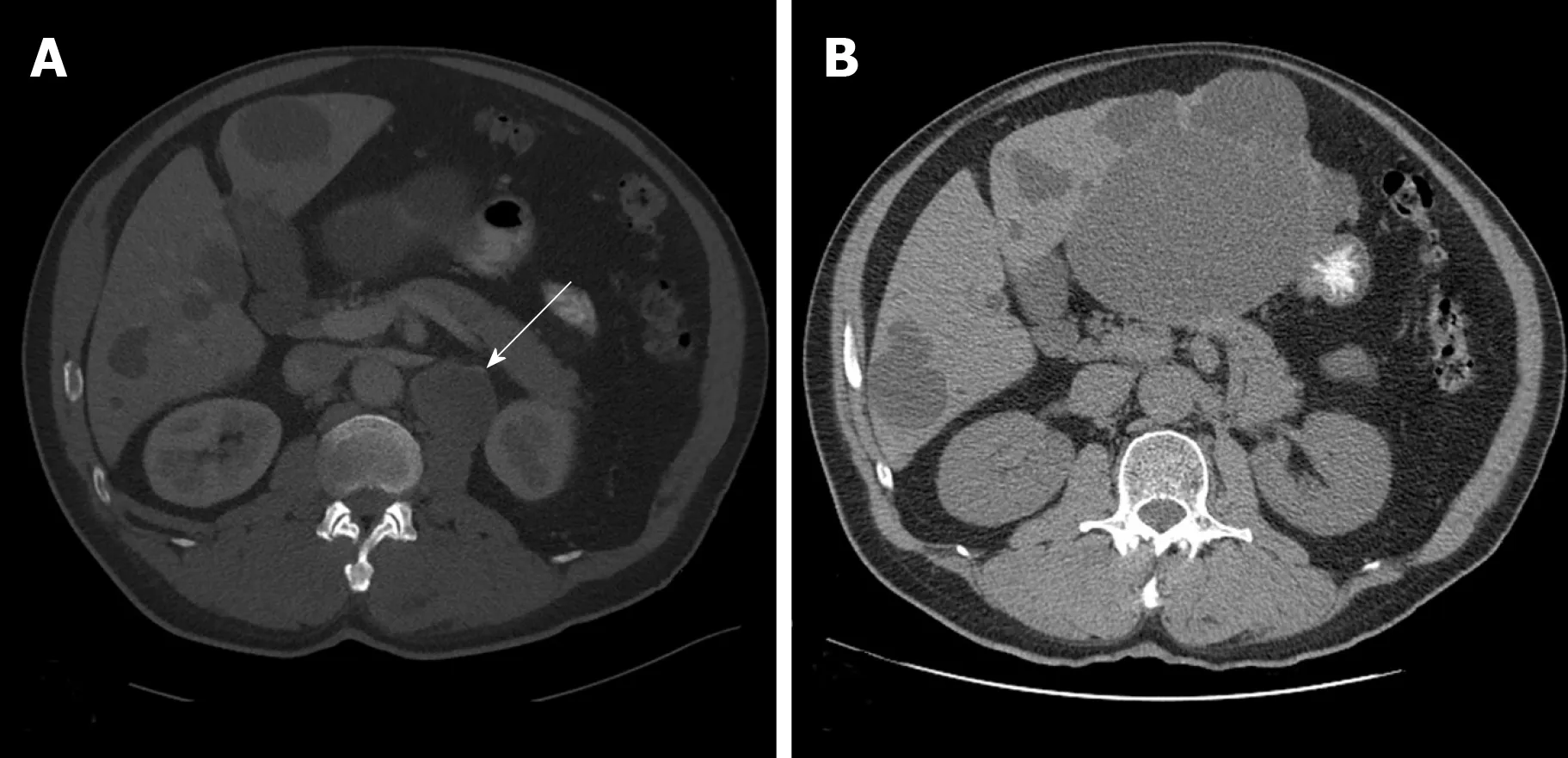

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis showed a 1.8 cm left retroperitoneal lymph node which was concerning for malignancy (Figure 1A). There was no evidence of renal pathology. A positron emission tomography/CT revealed intense fluorine-18-deoxyglucose activity in the left retroperitoneal soft tissue nodule adjacent to the medial limb of the left adrenal gland (Figure 2). The standard uptake volume was 12.4.

A core biopsy was performed under CT guidance of the left para-aortic lymph node. The immunohistochemical stains were strong and diffusely positive for PAX8 and cytokeratin (CK) AE1 and AE3 and negative for prostate-specific antigen (PSA),prostate specific acid phosphatase, Inhibin, and melanocyte antigen related to T-cells-1. Although the primary tumor site was unknown, the morphological and immunohistochemical features were most consistent with CCRCC.

Restaging studies by bone scan 6 wk later were negative for skeletal metastasis. An abdominal and pelvic CT scan with and without Gadolinium contrast demonstrated a significant increase in size of the hypoenhancing retroperitoneal lymph node (4.3 cm× 4.4 cm compared to 1.8 cm × 2.8 cm 8 mo earlier). A primary lesion in the renal collecting system or ureters was not observed, although the prostate was markedly enlarged and there was diffuse bladder wall thickening.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

Metastatic CCRCC in isolated retroperitoneal lymph node without evidence of primary tumor in kidneys.

TREATMENT

A retroperitoneal LND was performed 3 mo following the biopsy. The single lymph node mass was 5.5 cm in greatest dimension with extensive necrosis. Margins of resection were negative. Two additional benign lymph nodes in the supra-hilar area and 14 lymph nodes in the left periaortic region were also resected, all of which were negative for pathologic changes. The retroperitoneal lymph node was most compatible with CCRCC. A nephrectomy was not conducted as a renal mass had not been detected on any prior imaging studies. The patient did not receive any type of adjuvant therapy.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

The patient underwent surveillance with serial CT scans with contrast of the chest,abdomen, and pelvis for the next 5 years, all of which demonstrated no recurrent or metastatic disease and no evidence of retroperitoneal adenopathy (Figure 1B).

DISCUSSION

Immunohistochemical markers may shed light on the differential diagnosis in isolated metastatic adenopathy. Paired-box genes (PAX) are not only essential for determining cell fate during the development of the thyroid, kidney, and Müllerian system, but PAX8 is found at high levels in specific types of tumors, including thyroid, renal, and ovarian carcinomas as well as pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors[16]. PAX8 has also been identified in upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma. Positivity of tumor cells with CK AE1/AE3 is strongly associated with CCRCC with 100% specificity and 88% sensitivity[17].

Figure 1 A computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis. A: A 1.8 cm left retroperitoneal lymph node which was concerning for malignancy (arrow); B: No recurrent or metastatic disease and no evidence of retroperitoneal adenopathy observed 5 years following the lymph node dissection.

The present case posed a dilemma due to the inconsistency between the immunohistochemical conclusions and the radiological findings of the isolated biopsy-proven metastatic retroperitoneal lymph node. The positive nuclear staining of both PAX8 and CK AE1 and AE3 suggested a CCRCC, however, the lack of renal pathology on all previous radiological examinations prompted an investigation of a primary site other than renal. Several neoplasms were included in the differential diagnosis, as highlighted in Table 1. Given the history and morphological features,urothelial carcinoma in the upper urinary tract was considered. Additionally, thyroid or thymic neoplasms were also in the differential diagnosis, although it was unlikely that they would have metastasized to a retroperitoneal lymph node. Other possibilities included primary adenocarcinoma of the retroperitoneum, lymphoma,and a testicular malignancy although there was no overtly suspicious mass noted on a scrotal ultrasound. Due to the patient’s history of severe prostatic enlargement, a primary malignancy of the prostate was also broached. Despite numerous oncological malignancies in the differential diagnosis, the lymph node in the left para-aortic space in our case was most likely a CCRCC based on immunohistochemical and morphological features. A nephrectomy was not performed as renal abnormalities on imaging were never observed. Although the prognosis of an isolated retroperitoneal lymph node with RCC is usually poor, our patient had no recurrent or metastatic disease and no evidence of retroperitoneal adenopathy 5 years following his LND.

Lymphatic drainage in RCC has been investigated in cadaveric and sentinel lymph node mapping studies which revealed the basic anatomy and its variability[9]. The discovery of peripheral lympho-venous communications in RCC has led to two varying mechanisms of RCC metastasis: (1) Hematogenous metastasis in RCC originates from lympho-venous anastomoses between the primary tumor and sentinel lymph nodes; and (2) RCC initially spreads hematogenously with lymph node involvement occurring later[9]. Brufau and colleagues reported that lymph node metastasis (22%) is the third most common site of RCC metastasis, following lung(45%) and bone (30%)[5,18].

Lymph node involvement is based on morphological criteria, with a normal lymph node having a maximum short-axis diameter of 10 mm or less[5]. The single para-aortic lymph node mass in our case was 5.5 cm in greatest dimension with extensive necrosis. Several features are specific to lymph node metastases of RCC. A higher rate of reactive lymphadenopathy in RCC may be observed associated with primary tumor necrosis or thrombus within the inferior vena cava which increases the falsepositive rates for the 10 mm cutoff[19]. Additionally, hypervascular lymph nodes are commonly detected in CCRCC which may resemble vascular structures when they are small[20]. Although it has been reported that most lymph node metastases in RCC are accompanied by distant metastasis[8], our patient displayed lymph node metastasis without any other evidence of metastases.

Spontaneous regression refers to the partial or complete disappearance of a malignant tumor in the absence of all treatment or in the presence of therapy which is considered inadequate[21]. The frequency of spontaneous regression of RCC ranges between 0.5%- 7.0%[22,23]. In Janiszewska et al[24]40-year review of 59 cases of spontaneous regression of RCC, the cases were categorized into 3 groups: (1)Regression of RCC metastasis (n = 48; 30 in the lungs); (2) Delayed metastases (n = 6; 5 in the lungs); and (3) Regression of the primary tumor (n = 5)[24]. The latter cases were associated either with previous hemorrhage into the tumor or with renal vein emboli.While the mechanism is not fully understood, immunologic factors most likely play a pivotal role[25]. It is theorized that innate immune cells may recognize distinct structures on cancer cells which trigger complete regression of the primary malignancy[25]. Complete spontaneous regression of primary malignant melanoma is a well-described phenomenon, reported in the literature since 1866[25,26]. RCC and melanoma share some similarities in patterns of metastasis and responses to immunotherapy. A strong bidirectional association has been observed between RCC and melanoma[27,28]. We hypothesize that the primary RCC in our case most likely spontaneously regressed prior to the detection of the single metastatic retroperitoneal lymph node.

Figure 2 A positron emission tomography/computed tomography revealed intense fluorine-18-deoxyglucose activity in the left retroperitoneal soft tissue nodule adjacent to the medial limb of the left adrenal gland(arrow).

CONCLUSION

A metastatic clear cell carcinoma with an unknown primary site warrants a thorough investigation into the neoplasms that may metastasize to a solitary retroperitoneal lymph node. The unusual presentation of CCRCC without a primary tumor in the kidney in our case stresses the importance of a potential curative role for metastasectomy without a need for nephrectomy. Long-term surveillance imaging studies may be necessary to detect potential recurrent disease.

Table 1 Differential diagnosis of isolated biopsy-proven metastatic retroperitoneal lymph node

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge Norton Healthcare for their continued support.

World Journal of Clinical Oncology2020年2期

World Journal of Clinical Oncology2020年2期

- World Journal of Clinical Oncology的其它文章

- Can epigenetic and inflammatory biomarkers identify clinically aggressive prostate cancer?

- Objective response rate assessment in oncology:Current situation and future expectations

- Abdominal metastases of primary extremity soft tissue sarcoma:A systematic review

- Pancreatic adenocarcinoma with early esophageal metastasis:A case report and review of literature

- Pituitary carcinoma: Two case reports and review of literature