期待一场歌剧“弥赛亚”

司马勤

不久之前——好吧,从今天算起,那是几年前的事了——我曾提出疑问,为什么歌剧世界里没有像亨德尔的《弥赛亚》(Messiah)或柴可夫斯基的《胡桃夹子》(Nutcracker)那样的,在音乐厅和芭蕾舞台搬演的“圣诞必选剧目”。当然,有不少歌剧的情节与圣诞有关,其中包括《波希米亚人》(La bohème)这部可说是史上最受欢迎的歌剧作品。但是,《波希米亚人》也不能归类为圣诞“应季”歌剧,正如电影《虎胆龙威》(Die Hard)不能算是“圣诞电影”一样,尽管两部作品的故事背景都发生在圣诞假期前夕。一部真正关乎圣诞的歌剧,需要与圣诞的原本故事有关,并具有独特的演绎;或者起码,必须包含所谓的圣诞节日精神。但最重要的是,演出必须要成为一种每年一度的传统。

当年,我在文章里提到了一些作品,尤其是约翰·亚当斯(John Adams)運用独特手法引用圣诞故事的《厄尔尼诺》(El Ni?o,西班牙语“圣婴”之意)。然而,就传统而言,我的首选是吉安·卡洛·梅诺蒂的《阿玛尔与夜访者》(Amahl and the Night Visitors)。这是一部20世纪50年代原先为电视媒体而创作的歌剧,内容与叙事方式也很独特,后来成为每年一度的全国电视广播(先是现场直播,后来通过录播进行重放)。2018年12月,我错过了《厄尔尼诺》的重演,但我有机会看到了现场歌剧团(On Site Opera)搬演的《阿玛尔》。该制作重新演绎了最表面的情节——将背景变为一对难民夫妇寻找安居之所时面临困境的故事——并在一个真正的难民收容所上演。

现场歌剧团的这版制作轻而易举地满足了“圣诞歌剧”的必要条件;事实上,我认为没有人能比梅诺蒂在音乐中更好地捕捉到圣诞精神,而这个独特制作可谓是“完美音调”(pitch perfect)。当歌剧团于2019年12月在同一个教堂兼收容所再次搬演《阿玛尔》时,我猜测一个新传统即将诞生。可惜,在此后什么都发生——不需加以解释,整个世界都停顿下来。当然,还有另外的因素:现场歌剧团后来更换了新的艺术总监,制作计划一切向前看,因此那些过去的“传统”不会再被提上议程。

这让我们突然跳回到《厄尔尼诺》。由于平常没时间慢慢细品自己失之交臂的演出,因此至今我都没有捞到机会研究2018年《厄尔尼诺》复排背后的故事。那完全是我的损失。因为《厄尔尼诺》如何以现在的形式亮相舞台的来龙去脉,可能要比作品本身更能引起大众的兴趣。

***

在2000年,当约翰·亚当斯与彼得·塞拉斯(Peter Sellars)首次推出他们的“耶稣诞生歌剧/清唱剧”时,两人并没有立志取替或创造一部另类的《弥赛亚》的意向,但后来的成绩却不言自明。《弥赛亚》的英文唱词节选自英国国王译本的《新约》和《旧约》(1611年出版,至今通行全球),而塞拉斯的《厄尔尼诺》文本内容除了涉及《新约》《旧约》以外,还包括早期的《诺斯底福音书》、马丁·路德(Martin Luther)的布道,和几位拉丁美洲诗人的诗歌作品。与《弥塞尔》讲述耶稣生与死的预言不同,《厄尔尼诺》主要聚焦于耶稣出生的情节,尤其是母子之间的关系。

明眼人很快就看出,无论是规模或时长,这部作品与亨德尔都有千丝万缕的联系。《厄尔尼诺》用上大型交响乐配器、成人与儿童合唱团以及六位独唱家,其中包括三位高男高音。整部作品差不多历时两小时——以巴洛克时期的标准来看不算太长,但对于21世纪来说,这是一个史诗般的夜晚。亚当斯与塞拉斯的这部作品自首演以来一帆风顺,在世界各地曾多次现场演出——有歌剧形式的也有音乐会形式的,充分配合这部“歌剧/清唱剧”作品的双重身份。《厄尔尼诺》至今已出版了备受追捧的录音与录像版本。但在过去几年里,参与首演的两位独唱家——女高音道恩·厄普肖(Dawn Upshaw)与低男中音威拉德·怀特(Willard White)已经退休,另一位独唱家女中音洛林·亨特·里贝尔逊(Lorraine Hunt Lieberson)因癌症不幸去世。亚当斯与塞拉斯两人也因参与了不同的项目而分道扬镳。

在这种背景下,女高音茱莉亚·布洛克(Julia Bullock)挑起重担。她是道恩·厄普肖的弟子,亚当斯最喜欢的合作伙伴。在接过大都会博物馆驻院艺术家一职后,她受邀在大都会位于曼哈顿北部专门展示中世纪作品的分馆修道院艺术博物馆(The Cloisters)举行一场圣诞音乐会。她很有兴趣搬演《厄尔尼诺》,但修道院艺术博物馆并没有合适的空间及资源搬演大版本的制作。因此,布洛克提议重新制作一个“小教堂版本”(chapel version),而不是原作那样宏大的大教堂(或大音乐厅)版。

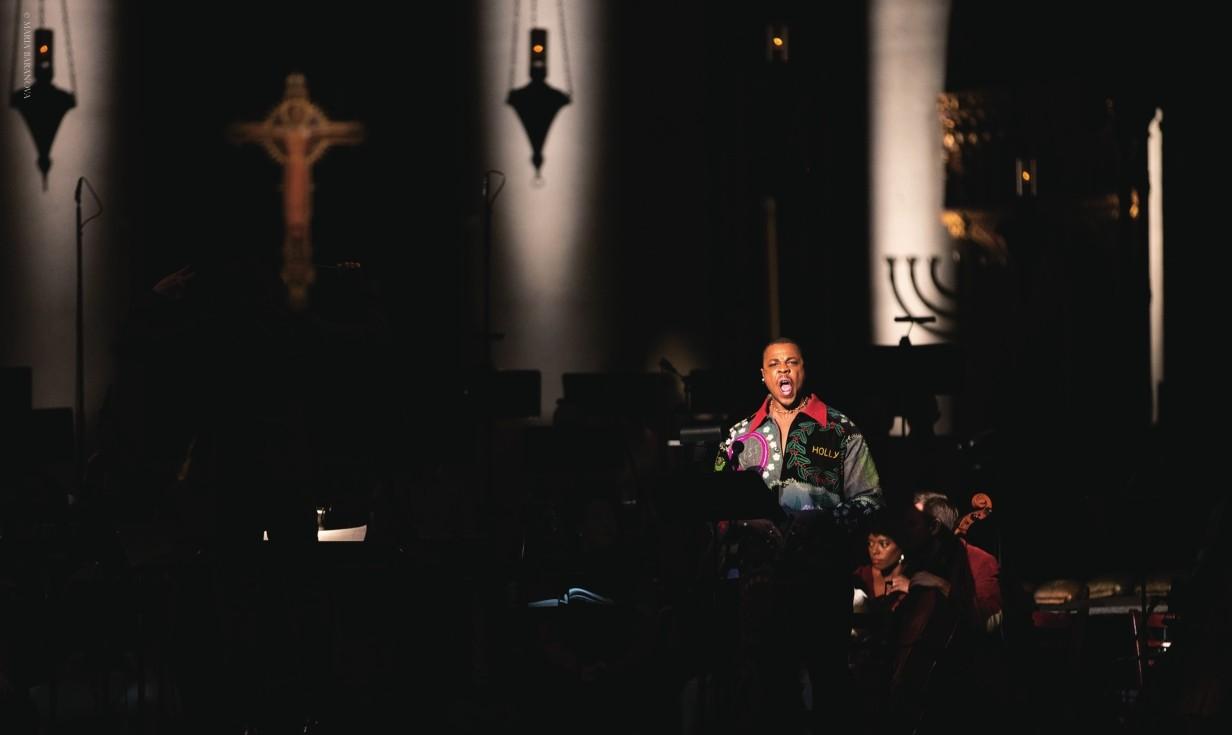

布洛克描述她心目中的“浓缩版”《厄尔尼诺》(无论时长还是资源)不是“改编版”而是“过滤版”(这个制作的副题是“重新考虑圣诞”)。亚当斯当即同意了她。后来这个版本变成一个家庭项目,无论是从字面上——该制作由布洛克的丈夫克里斯蒂安·雷夫(Christian Reif)担任指挥以及联合编曲,还是从寓意上——这个制作也成为美国现代歌剧团(American Modern Opera Company,简称AMOC)首次亮相纽约的契机,该歌剧团刚刚在一年前才成立。布洛克邀请了三位歌唱家共同参与,他们都是在当今歌剧舞台上冉冉上升的新星:乔奈·布里奇斯(JNai Bridges)、安东尼·罗斯·科斯坦佐(Anthony Roth Costanzo)与达璜·泰尼斯(Davóne Tines)。作为大都会博物馆虚拟藏品的一部分,这场演出被精彩地拍摄下来,至今还能在视频网站上看得到。

后来,当现场歌剧院的《阿瑪尔》尘封已久,《厄尔尼诺》的影响就越来越强。2022年12月,AMOC再次搬演了他们的制作,这一次不是在小教堂,而是移师至纽约偌大的圣约翰大教堂。到了2023年,同一个制作在结束全美巡演后,再次重返圣约翰大教堂,与之合作的是鼎鼎大名的华尔街圣三一教堂合唱团。就像同名的热带海洋异常气候现象一般,这部歌剧显然变得举足轻重起来。

***

“一开始,只是‘弥赛亚。加上冠词之后好像显得过分肯定。但只有上帝才知道,亨德尔的《弥赛亚》中没有任何肯定的部分。”

以上是我毕生首次发表的乐评文章中的开场白。那年,编辑安排我报道12月纽约市举行的20多场亨德尔《弥赛亚》演出,其中每一场演出都是不一样的。

那一年,教堂与音乐厅都在搬演《弥赛亚》,从小型古乐团到大型交响乐团。某些独唱家是巴洛克风格的专家,也会有几位大都会歌剧院最热门的明星。其中的一个版本让合唱团员轮流出来演唱咏叹调;另一个则邀请观众参与合唱段落。大部分的演出都沿用了亨德尔为科文特花园剧院创作的版本,但有一个团体吹嘘自己找来了作曲家1742年都柏林首演时的原版乐谱。另一个版本甚至使用了莫扎特后来的配器。

这就是定义可能变得棘手的地方。“传统”经常意味着束缚,没有任何变化或改动的空间。但是,有些东西可能正是如此的传统,以至于无论你怎么改变它,原始的精神都会显现出来。亨德尔的《弥赛亚》是一个绝好的例子——或者是音乐史上最强的一个例子。

因此,我们很难推算出某部新歌剧将来能否与《弥赛亚》抗衡而成为“节日必选”,但是,大家还是应该看看《厄尔尼诺》的现状。首先,首轮演出势如破竹,十分成功。第二,新生代歌唱家十分投入,参与其中。第三,这部作品已经出现不同版本,可以根据场地与演出条件,伸缩自如。事实上,亚当斯的原版将于2024年春天以全新制作于大都会歌剧院亮相,导演丽丽安娜·布莱恩-克鲁斯(Lileana Blaine-Cruz),指挥马琳·阿索普(Marin Alsop),演员阵容包括布洛克、布里奇斯、泰尼斯与达尼尔拉·马克(Daniella Mack)。

令人遗憾的是,时至今日,这并不是世界各地的合唱团体很快就会争相推出的那种作品。《厄尔尼诺》中也没有“哈利路亚”般的大合唱,那种让观众全体站立的祭礼式传统。但是,它能否成为新的“节日传统”?就我个人而言,我觉得大可拭目以待。

A while back—okay, it was several years ago now—I asked why there was no “Christmas opera” in the way that Handels Messiah and Tchaikovskys Nutcracker have become holiday staples on the concert and ballet stages. Oh sure, we have operas set during Christmas— including La bohème, arguably the most popular opera in the repertory. But Bohème is no more a Christmas opera than Die Hard is a “Christmas film” just because both stories take place on the eve of the holiday. A proper Christmas opera needs to have a distinctive take on the Christmas story, or at the very least embody the spirit of the season. And above all, it has to become a tradition.

Back then, Id mentioned a few pieces, not least John Adamss El Ni?o, as taking such a singular approach. As far as tradition goes, though, my top pick was Gian Carlo Menottis Amahl and the Night Visitors, another distinctive retelling originally written for television in the early 1950s that had actually become an annual event for a time in that medium (first in live performances, later through yearly broadcasts of the recorded video). Id missed the revival of El Ni?o in December 2018, but I did catch On Site Operas production of Amahl that year, which took the story at face value—a migrant couple searching for shelter in a time of need—by staging it in an actual homeless shelter.

That production immediately filled the first criterion of a Christmas opera; I dont think anyone, in fact, has ever captured the spirit of the holiday better in music than Menotti, and On Site Operas realization was pitch perfect. When the company revived its production in December 2019 at the same location, I thought we were actually gearing up for a tradition. But after that, nothing. For some reasons we probably dont need to go into at this point, the world suddenly shut down. But for other reasons, On Site Opera has a new artistic director and the company is looking forward, so “tradition” as such is no longer on the agenda.

Which suddenly brings us back to El Ni?o. Since I often dont always get to read about performances I cant attend, I missed the back story of the pieces 2018 revival. My loss totally, since the story of how El Ni?o made it back to the stage in its current form is possibly more interesting than the piece itself.

***

When John Adams and Peter Sellars first unveiled their “nativity opera-oratorio” in 2000, they hadnt overtly planned to create an alternative Messiah, but the results speak for themselves. Unlike Messiah, with texts taken exclusively from the Old Testament in the King James translation, Sellars text for El Ni?o draws on both the Old and New Testaments as well as the gnostic gospels, Martin Luthers sermons and a hand- ful of Latin American poets. Unlike Messiah, which essentially showcases prophecies of the life and death of Christ, El Ni?o focuses heavily on Jesuss birth, particularly on the relationship between mother and child.

The connections to Handel quickly became obvious to some observers, both in scope and duration. El Ni?o called for a large orchestra, choruses of adults and children, and six soloists, including three countertenors. It also ran for nearly two hours—not a long evening by Baroque standards, but suitably epic for the 21st century. Adams and Sellars had a good run with the piece, with numerous live performances around the world—some staged, some not, befitting a piece billed as an “opera-oratorio.” Likewise, El Ni?o had prominent recordings both on CD and DVD. But within a few years, two of the original soloists (soprano Dawn Upshaw and bass-baritone Willard White) had retired from performing and the third (mezzo-soprano Lorraine Hunt Lieberson) had died of cancer. Adams and Sellars, too, had gone on to different projects.

Enter Julia Bullock, a protégé of Upshaw and a favorite collaborator of Adams. After being appointed a resident artist at New Yorks Metropolitan Museum of Art, the soprano was approached to present a holiday concert at The Cloisters, the museums Medieval collection in upper Manhattan. Her thoughts kept coming back to El Ni?o, but she had neither the space nor the resources for a production of that scale. So rather than a grand statement, suitable for cathedrals either religious or secular, Bullock proposed a “chapel version.”

In proposing a reduction both in duration and resources, Bullock described her version not as an“arrangement” but rather a “distilled rendering” (its subtitle, in fact, was “Nativity Reconsidered”). Adams agreed immediately to the cuts and reorchestration, and the production made its way to The Cloisters essentially as a family project both literally—Bullocks husband Christian Reif was both conductor and coarranger—and figuratively, since the effort would mark the New York debut of the American Modern Opera Company, which had been formed only the year before. Joining Bullock were fellow AMOC members Jnai Bridges, Anthony Roth Costanzo and Davóne Tines, three of the most promising singers on the opera stage today. The performance was brilliantly filmed and still lives on YouTube as part of the Met Museums virtual offerings.

But then, while On Site Operas Amahl went quiet, El Ni?o gained further traction. In December 2022, AMOC revived their production not in a chapel-sized venue, but rather New Yorks massive Cathedral of St. John the Divine. In 2023, the company returned to St. Johns, capping a national tour of the production, this time collaborating with the Choir of Trinity Church Wall Street. Like the atmospheric phenomenon of the same name, El Ni?o has clearly become a force to be reckoned with.

***

First of all, its just “Messiah.” Adding the article makes it all seem too, well, definite. And Lord knows, theres nothing definite about Handels “Messiah.”

Those were the first words of my first published article about music. Id been commissioned to write a piece that would make sense of 20 different performances of Handels oratorio in New York that December, no two of them alike.

That year, Messiah was appearing in churches and concert halls, with period-instrument ensembles and full-blown symphony orchestras. Some soloists were Baroque specialists, others were A-list singers from the Metropolitan Opera. One version had individual chorus members stepping out to sing the solo movements; another had the audience singing the choruses themselves. Most performances stuck with the score Handel wrote for Londons Covent Garden Theatre, though one version boasted of using the composers original 1742 version from Dublin. Another version even used the later orchestration by Mozart.

This is where definitions can get tricky. Often, the word “tradition” is a straitjacket that allows no room for change or alteration. On the other hand, something can be so traditional that, however much you change it, the original spirit still comes through. Handels Messiah is such a piece—perhaps more so than any other work in musical history.

So while its not realistic to expect any new opera to compete with Messiah as a holiday favorite, lets see where we are with El Ni?o. First, the piece had a highly successful initial run. Second, a new generation of performers have taken up the cause. Third, different versions of the piece now exist, allowing it to expand or contract based on the venue or performance situation (Adamss original version, in fact, will appear in a new production by Lileana BlaineCruz, conducted by Marin Alsop, this spring at the Metropolitan Opera, with Bullock, Bridges and Tines as well as Daniella Mack).

On the downside, this is not exactly the kind of piece that choral societies around the world will be rushing to anytime soon. Nor does El Ni?o have a “Hallelujah”Chorus, where audiences can stand as a ritual mark of recognition. But in terms of becoming a holiday tradition? Personally, I think the show has a shot.

——透析阿甘本的弥赛亚主义

——亨德尔